Preserving the Non-Proliferation Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Transcript

9TH A NNUAL Frank K. Kelly Lecture ON HUMANITY’S FUTURE AMBASSADOR Max Kampelman ZERO NUCLEAR WEAPONS FOR A SANE AND SUSTAINABLE WORLD NUCLEAR AGE PEACE FOUNDATION Working for a World Free of Nuclear Weapons EMPOWERING PEACE LEADERS Strengthening International Law Frank K. Kelly Lecture ON HUMANITY’S FUTURE he Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future was established by the Nuclear Age Peace TFoundation in 2002. The lecture series honors Frank Kelly, a founder and senior vice president of the Foundation, whose vision and compassion are perpetuated through this ongoing lecture series. Each annual lecture is presented by a distin - guished individual to explore the contours of humanity’s present circumstances and ways by which we can shape a more promising future for our planet and all its inhabitants. Mr. Kelly, for whom the lecture series is named, gave the inaugural lecture in 2002 on “Glorious Beings: What We Are and What We May Become.” The lecture presented in this booklet, “Zero Nuclear Weapons for a Sane and Sustainable World,” is the ninth in the series. It was presented by Ambassador Max Kampelman at Santa Barbara City College on February 25, 2010. The 2009 lecture was presented by Frances Moore Lappé on “Living Democracy, Feeding Hope.” The 2008 lecture was given by Colman McCarthy on “Teach Peace.” The 2007 lecture was delivered by Jakob von Uexküll on “Globalization: Values, Responsibil - ity and Global Justice.” The 2006 lecture was presented by Nobel Peace Laureate Mairead Corrigan Maguire on “A Right to Live without Violence, Nuclear Weapons and War.” The 2005 lecture was delivered by Dr. -

Democracy's Champion: Albert Shanker and The

DEMOCRACY’S CHAMPION ALBERT SHANKER and the International Impact of the American Federation of Teachers By Eric Chenoweth BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paul E. Almeida Anthony Bryk Barbara Byrd-Bennett Landon Butler David K. Cohen Thomas R. Donahue Han Dongfang Bob Edwards Carl Gershman The Albert Shanker Institute is a nonprofit organization established in 1998 to honor the life and legacy of the late president of the Milton Goldberg American Federation of Teachers. The organization’s by-laws Ernest G. Green commit it to four fundamental principles—vibrant democracy, Linda Darling Hammond quality public education, a voice for working people in decisions E. D. Hirsch, Jr. affecting their jobs and their lives, and free and open debate about Sol Hurwitz all of these issues. John Jackson Clifford B. Janey The institute brings together influential leaders and thinkers from Lorretta Johnson business, labor, government, and education from across the political Susan Moore Johnson spectrum. It sponsors research, promotes discussions, and seeks new Ted Kirsch and workable approaches to the issues that will shape the future of Francine Lawrence democracy, education, and unionism. Many of these conversations Stanley S. Litow are off-the-record, encouraging lively, honest debate and new Michael Maccoby understandings. Herb Magidson Harold Meyerson These efforts are directed by and accountable to a diverse and Mary Cathryn Ricker distinguished board of directors representing the richness of Al Richard Riley Shanker’s commitments and concerns. William Schmidt Randi Weingarten ____________________________________________ Deborah L. Wince-Smith This document was written for the Albert Shanker Institute and does not necessarily represent the views of the institute or the members of its Board EMERITUS BOARD of Directors. -

13. Part Two: Turning the Goal of a World Without Nuclear Weapons Into a Joint Enterprise Max M

13. Part Two: Turning the Goal of a World without Nuclear Weapons into a Joint Enterprise Max M. Kampelman Steven P. Andreasen Key Judgments ● This paper focuses on two related questions pertaining to the issue of how best to work with leaders of the countries in possession of nuclear weapons to turn the goal of a world without nuclear weapons into a joint enterprise: • What would be the “mechanism” for getting all of the nuclear states together to agree on a program of action such as the steps listed in the Wall Street Journal Op-Ed article? • Would a new mechanism—either formal or informal—be re- quired, or would this best be done through an existing mech- anism, such as the United Nations, perhaps working with other key states? ● The review identified four central issues for analysis: • Issue 1: How can the United States government initiate the process of working with leaders of other nuclear weapon states to turn the goal of a world without nuclear weapons into a joint enterprise? • Issue 2: To what extent does this process need to be proce- durally and substantively “inclusive” (i.e., involve all nuclear weapons states) from the start? 430 Max M. Kampelman and Steven Andreasen • Issue 3: Should the process be centered within existing struc- tures and mechanisms or on a more ad hoc basis? • Issue 4: How much “weight” should be given to the steps at the outset of this process? ● The review identified three options for consideration: • Option 1: A UN-centered process, whereby the UN General Assembly would first pass a resolution calling for the elimi- nation of all weapons of mass destruction, followed by a pro- cess anchored in the Security Council. -

Max Kampelman at This Telephone Number; He‘Ll Be at the Bookstore

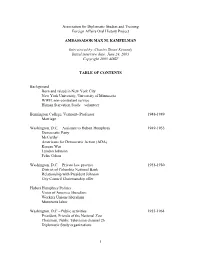

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR MAX M. KAMPELMAN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 24, 2003 Copyright 2005 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Ne York City Ne York University, University of Minnesota WWII, non-combatant service Human Starvation Study + volunteer Bennington College, ,ermont- Professor 19.8-19.9 Marriage Washington, D.C. + Assistant to Hubert Humphrey 19.9-1922 Democratic Party McCarthy Americans for Democratic Action 3ADA4 5orean War 6yndon 7ohnson Feli8 Cohen Washington, D.C. + Private la practice 1922-1980 District of Columbia National Bank Relationship ith President 7ohnson City Council Chairmanship offer Hubert Humphrey Politics ,oice of America liberalism Workers Unions liberalism Minnesota labor Washington, D.C + Public activities 1922-196. President, Friends of the National Zoo Chairman, Public Television channel 26 Diplomatic Study organizations 1 Presidential Campaigns 196., 1968 and 1972 6yndon 7ohnson Hubert Humphrey ,ice-President@s Residence ,ietnam ,ice-Presidential candidates McAovern Richard Ni8on 7ack 5ennedy Committee on the Present Danger Presidential Elections 1976 Henry 3Scoop4 7ackson Hubert Humphrey Walter Mondale President 7immy Carter years 1977-1981 Afghanistan Madrid Conference + Chief of Delegation William Scranton Dante Fascell Helsinki Final Act Revie Arthur Aoldberg + Mid-East negotiator Aermans in USSR Soviet 7e s President Reagan Years + US Rep., Arms Reduction Negotiations -

Revisiting Reykjavik Revisited the 25Th Anniversary of a Remarkable Meeting

Revisiting Reykjavik Revisited The 25th Anniversary of a Remarkable Meeting by RiChard rhodes PuliZTer-PriZe winner This year, 2011, marks the 25th and arms negotiator Max Kampelman by former Secretaries of State George anniversary of the astonishing meeting and Stanford University physicist Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former in Reykjavik, Iceland, in October 1986 and longstanding government adviser Secretary of Defense William Perry and between Soviet General Secretary Sidney Drell, discovered a common and former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn. Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President urgent concern with renewed nuclear Ronald Reagan. That meeting very peril. In particular, terrorist attacks by “Nuclear weapons today present nearly led to an agreement to begin the a sub-national group, al Qaeda, had tremendous dangers, but also an historic process of eliminating nuclear weapons raised the spectre of nuclear terrorism opportunity,” the editorial began. from the world. Ultimately the two undeterred by the threat of nuclear “U.S. leadership will be required to leaders were unable to agree, but both retaliation. There was uncertainty as take the world to the next stage—to a understood their negotiations to have well about how long the grand bargain solid consensus for reversing reliance been uniquely fruitful, as indeed they of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation on nuclear weapons globally as a were. “Seen by many as a failure,” Treaty would hold when the nuclear vital contribution to preventing their Gorbachev wrote later, the Reykjavik powers continued to shirk their proliferation into potentially dangerous Summit “actually gave an impetus to commitment to the non-nuclear hands, and ultimately ending them as a reduction by reaffirming the vision of powers to move expeditiously toward threat to the world.” a world without nuclear weapons and nuclear disarmament. -

USIP Receives $10 Million for Headquarters Project Great Hall to Be Named for George P

May/JUne 2007 Inside 3 Shultz Speech 4 USIP On the Ground 7 Public Health Project 9 Fellowship Vol. XIII, No. 1 Program 10 Focus on Iraq United StateS inStitUte of Peace ■ WaShington, d.c. ■ www.usip.org 14 Short Takes 19 Letter from Nigeria USIP Receives $10 Million for Headquarters Project Great Hall to Be Named for George P. Shultz “Chevron’s contribution is an investment in the global peacebuilding efforts of the Institute.” —David O’Reilly “Having the Institute’s Great Hall bear [Shultz’s] name is an honor and a privilege.” —J. Robinson West Chevron CEO David O’Reilly (left); and J. Robinson West, USIP board chair, and Richard Solomon, USIP president, speak at a dinner celebrating Chevron’s contribution to the Institute. he U.S. Institute of on international conflict preven- the Institute’s new headquarters Peace has received a $10 tion, management, and resolution. project comes at a significant million contribution The Institute plans to name the moment…. [The new building] from the Chevron Cor- great hall at the new building the will increase the Institute’s capac- poration to help con- George P. Shultz Great Hall, in ity and our ability to reach out to struct its new permanent honor of the former U.S. secretary the American public and the headquarters at the of state. The theater in the Public world.” northwest corner of the National Education Center will be identi- He continued, “During the last TMall in Washington, D.C. The fied as the Chevron Theater. two decades, we have worked to headquarters will serve as a Speaking at a dinner at which promote skills in international national center of innovation for those plans were announced, Insti- conflict management as an essen- research, education, training, and tute president Richard Solomon tial element of diplomacy and for- policy and program development affirmed, “Chevron’s support for See Chevron, page 2 U.S. -

Gillespie, Jacob

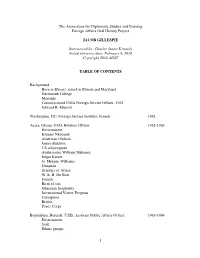

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JACOB GILLESPIE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 4, 2010 Copyright 2016 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Illinois; raised in Illinois and Maryland Dartmouth College Marriage Commissioned USIA Foreign Service Officer, 1961 Edward R. Murrow Washington, DC: Foreign Service Institute; French 1962 Accra, Ghana: USIA Rotation Officer 1962-1963 Environment Kwame Nkrumah American Outlook James Baldwin US aid program Ambassador William Mahoney Edgar Kaiser G. Mennen Williams Danquah Scholars of Africa W. E, B. Du Bois French Birth of son Ghanaian hospitality International Visitor Program Corruption British Peace Corps Bujumbura, Burundi: USIS, Assistant Public Affairs Officer 1963-1964 Environment Staff Ethnic groups 1 Government Tutsi refugee camps Communication facilities Elton Stepherson Kennedy assassination University of Butare Chinese officer defection Chinese official presence U.S. media Leopoldville, Republic of the Congo: Field Operations Officer; 1964-1966 Motion Pictures Officer Averill Harriman Consulate personnel hostages in Stanleyville Max Kraus Belgians retake Stanleyville Stanleyville devastation Ambassador Godley Work load Elizabethville Bukavu Environment Rebel activities Mike Hoare’s mercenaries South African mercenaries Motion Picture Distribution Mobutu Internal travels Coquilhatville Fred Hunter Industrial diamonds Exhibits Social life Parc Albert Hank Ryan Films production and distribution -

Zero Nuclear Weapons

Hoover Press : Drell Shultz hshultz ch8 Mp_97 rev1 page 97 Zero Nuclear Weapons Max M. Kampelman i consider it a privilege to be in your company and I know that we all consider it a privilege to have been invited here by George Shultz and Sidney Drell to note and evaluate the sig- nificance of the Reykjavik Summit twenty years ago between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, both of whom agreed that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” It is essential, as I rise to address you, that you be aware of my reluctant view that neither of our two national political parties today has demonstrated the capacity to govern our so- ciety in this period of international crisis. I, therefore, turn to this audience of scientists and experts for guidance. It is more than fifty-five years since I took leave from my college teaching to spend three months assisting the newly elected Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota to organize his office—and I am still in Washington. During my teaching days, Gunnar Myrdahl published his massive study of the Ne- gro in America. His dominant perception was the realization that wherever he went in our country, he noted a common theme—that of the principles of the Declaration of Indepen- dence. I then asked my students to recall that at the time the Declaration was adopted we had slavery, no legal equality for Ambassador Max Kampelman was Chief U.S. Negotiator to the Conference on Se- curity and Cooperation in Europe 1980–84 and head of the U.S.