Black Metal Machine Theorizing Industrial Black Metal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Grist Only on Soundcult Extreme Album Review

2/22/2018 Drumcorps – Grist only on Soundcult Extreme Album Review article quote Wanna find something? Drumcorps – Grist September 12, 2007 Fiend Leave a comment electronic, review breakcore, electronic, grindcore Album Reviews Music News Where to Send Promos Become a Editor About Us Copyright Policy Post Types Article Image Link Audio Video Quote Categories electronic metal news review rock Amazon Music Deals! Popular I could say i have a sort of love/hate relationship with grindcore, mostly because when its well made, it’s Kingcrow ‑ Insider completely and utterly awesome, but most of the times its just an amalgam of noise and not in the good sense, December 20, 2013 also i could say i have the same feeling with electronic music in general, so when Aaron Specter‘s Drumcorps no comments pulls this “Grist” saying it’s a mixing of grindcore and breakcore… i tend to take it with a grain of salt. It all starts up with “Botch Up and Die” and it’s pretty grindcore, kinda of a homage to Botch, with the eccentric Dark Tranquility and Sonata guitars over a grind blast beat, its not only amusing but quite groovy, nicely done, “Down” is kinda dance meets Arctica joined forces for Heavy noisecore with distorted samples and guitars into the mix, okkk, “Pig Destroyer Destroyer” has some nice Metal Poker Tournament drumming building to a slowed down chopped distorted noise filled beat … are we making fun of Pig Destroyer?, December 12, 2013 is this supposed to be a compliment or a satire, anyway it all builds up to a distorted guitar breakcore fest, no comments mixing real life drumming with beats and distortion…. -

![Forever the Black Smoke Blows in Krems’ [Auto-Translated from German]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7323/forever-the-black-smoke-blows-in-krems-auto-translated-from-german-257323.webp)

Forever the Black Smoke Blows in Krems’ [Auto-Translated from German]

Kramar, Thomas. ‘Forever the black smoke blows in Krems’ [Auto-translated from German]. Die Presse Online. 26 April 2018 Forever the black smoke blows in Krems In the nineties it was in vogue to state ends. Today one fears the "endless present": this is the motto of this year's Danube Festival. How postmodern is that? Or is it again - modern? The virtual source never runs dry: "Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas)", video by John Gerrard. – © Danube Festival It was an anticipated, much-anticipated eruption: on January 10, 1901, oil spewed from a well at Spindletop Hill (southeast Texas), yes: to splash. Two months later, the nearby town of Beaumont was a boomtown and its population tripled. The Irish artist John Gerrard recalls the time when oil spilled on Spindletop Hill. In his video installation "Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas)" he simulates that this source would never run dry, would never run out, but only bring more dirt, not juice for traffic and industry: black smoke is constantly pouring out of the jets, into shape a flag. Gerrard suggests a trivial interpretation. "Among the greatest legacies of the 20th century are not only the population explosion and the better living conditions, but also the significantly increased CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere," he writes: "This flag gives this invisible gas, this international danger, a picture, a way to represent oneself. " Heaven is where nothing happens Thomas Edlinger, Director of the Danube Festival, now places Gerrard's video installation in Krems in a new context of meaning - as an illustration of this year's theme: "Endless Presence". -

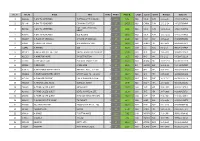

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

Pronunciation of Samael

Pronunciation of Samael http://www.omnilexica.com/pronunciation/?q=Samael How is Samael hyphenated? British usage: Samael (no hyphenation) American usage: Sa -mael Sorry, no pronunciation of Samael yet. Content is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License ; ad- ditional terms may apply. See Copyright for details. Keyword Tool | Romanian-English Dictionary Privacy Policy 1 of 1 6/14/2014 9:16 PM Samael definition/meaning http://www.omnilexica.com/?q=Samael On this page: Group Miscellanea Printed encyclopedias and other books with definitions for SAMAEL Online dictionaries and encyclopedias with entries for SAMAEL Photos about SAMAEL Scrabble value of S A M A E L 1 1 3 1 1 1 Anagrams of SAMAEL Share this page Samael is a industrial black metal band formed in 1987 in Sion, Switzerland. also known as Samaël members: Xytras since 1987 Vorph since 1987 Christophe Mermod since 1992 Makro since 2002 Kaos between 1996 and 2002 (6 years) Rodolphe between 1993 and 1996 (3 years) Christophe Mermod since 1991 Pat Charvet between 1987 and 1988 genres: Black metal, Dark metal, Industrial metal, Heavy metal , Symphonic metal, European industrial metal, Grindcore , 1 of 7 6/14/2014 9:17 PM Samael definition/meaning http://www.omnilexica.com/?q=Samael Symphonic black metal albums: "Into the Infernal Storm of Evil", "Macabre Operetta", "From Dark to Black", "Medieval Prophecy", "Worship Him", "Blood Ritual", "After the Sepulture", "1987–1992", "Ceremony of Opposites", "Rebel- lion", "Passage", "Exodus", "Eternal", "Black Trip", "Telepath", "Reign of Light", "On Earth", "Lessons in Magic #1", "Ceremony of Opposites / Re- bellion", "Aeonics: An Anthology", "Solar Soul", "Above", "Antigod", "Lux Mundi", "A Decade in Hell" official website: www.samael.info Samael is an important archangel in Talmudic and post-Talmudic lore, a figure who is accuser, seducer and destroyer, and has been regarded as both good and evil. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

Echo Beatty – 'Tidal Motions' (Icarus Records & Vynilla Vinyl) (Album

Echo Beatty – ‘Tidal Motions’ (Icarus Records & Vynilla Vinyl) (Album release: 28/01/2013 – Single ‘Tidal Motions’: 12/12/2012) The new Ghent-based label Icarus Records aims to be a platform for music that is undefined by musical borders. Antwerp-based duo Echo Beatty’s debut album ‘Tidal Motions’ is the first release on the label, a cooperation with Vynilla Vinyl. The album will be presented in Antwerp (Friday 18/01/13 - Salle Jeanne) and Ghent (Saturday 19/01/13 - Minardschouwburg). Echo Beatty Hailing from Antwerp, Echo Beatty are multi-instrumentalist Jochem Baelus and singer Annelies Van Dinter. It is February 2011, and Echo Beatty is the first-ever band to record an Icarus.fm livesession for Ghent-based radio station Urgent.fm. Consciously and continuously exploring their own musical limits, they use a wide array of homemade instruments, ranging from knitting needles and haircombs to musicboxes, to create their unpredictable and subtle trademark sound. Fragile yet sometimes aggressive. Light in some places, dark in others. Following the release of their first EP ‘Tiny Organs Of Trust’, and a small tour playing venues in Germany, The Netherlands and the Czech Republic, they temporarely move to Montreal in the spring of 2011 to work on new songs. There they join forces with producer Jeff Mc Murrich, known for prior collaborations with artists as Sandro Perri, Owen Pallett and Tindersticks. Tidal Motions Mc Murrich succesfully manages to capture Echo Beatty’s characteristical sound, that can be described as electric folk drenched in a subtle ‘Twin Peaks’’ atmosphere. ‘Tidal Motions’ is Echo Beatty’s very first full album. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE June 2017

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE June 2017 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you w ill find a full list w ith all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, w e have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 12.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they starte d with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

La Rebelión En El Heavy Metal La Colmena, Núm

La Colmena ISSN: 1405-6313 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Rivas Salgado, Sergio La rebelión en el Heavy Metal La Colmena, núm. 61-62, 2009, pp. 74-81 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=446344571009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Sergio Rivas Salgado La rebelión en el Heavy Mei e las manifestaciones humanas, pocas son las que resulta difícil definir. No se sabe qué es la filosofía, qué es la literatura ni. en el caso que se abordará, qué es el metal. Si se apresuran un poco las cosas, sí se sabe qué es. por ejemplo, la religión: en ésta se deben cumplir ciertas reglas que imponen hombres con más conocimiento de! mundo y todo está listo. El resto se podría llamar administración de la religión. La religión sería, así, una forma de concebir el mundo de acuerdo con el propósito de recibir un premio si se es bueno dentro de los terrenos morales del hombre; de tai suerte, éste se puede obtener por el simple hecho de vestir bien o por compartir los buenos deseos de un futuro luminoso para la humanidad. Todos los que entran en ese juego son beneficiados de una u otra manera. No es mi intención proponer una disputa sobre qué es la religión, ni sobre si la apreciación que hago deja mucho que desear; pero, como el metal no es obra de intelectuales sino de gente que se siente fastidiada de las reglas que la sociedad impone, debo apoyarme en esa definición tan sin fundamento para llegar al punto que quiero establecer. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you will find a full list with all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, we have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 11.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they started with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

You Won't Be Able to Stand Still When You Hear This

New Release Information uu April SINK THE SHIP Release Date Pre-Order Start Persevere uu 27/04/2018 uu 16/03/2018 uu Available as CD and LP Price Code: CD11 ST 4266-2 CD uu advertising in many important music magazines MAR/APR 2018 uu album reviews, interviews in all important Metal magazines in Europe’s MAR/APR 2018 issues uu song placements in European magazine compilations uu spotify playlists in all European territories uu retail marketing campaigns uu instore decoration: flyers, poster A1 uu Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Google+ organic promotion uu Facebook ads and promoted posts + Google ads in both the search and display networks, bing ads and gmail ads (tbc) uu Banner advertising on more than 60 most important Metal & Rock websites all over Europe uu additional booked ads on Metal Hammer Germany and UK, and in the Fixion network (mainly Blabbermouth) uu video and pre-roll ads on You tube Price Code: LP15 ST 4266-1 LP in sleeve uu ad campaigns on iPhones for iTunes and Google Play for Androids uu banners, featured items at the shop, header images and a back- ground on nuclearblast.de and nuclearblast.com uu features and banners in newsletters, as well as special mailings to targeted audiences in support of the release Territory: World YOU WON’T BE ABLE TO STAND STILL uu Tracklists: CD: 01. Second Chances 02. Out Of Here WHEN YOU HEAR THIS ALBUM 03. Domestic Dispute (Feat. Bert Poncet) 04. Everything (Feat. Levi Benton) 05. Nail Biter Just about anyone who has ever encountered adversity can tell you they have their own method of coping.