Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

2019 LS Polling Stations and Constituencies.Xlsx

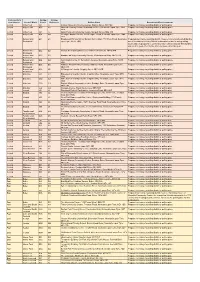

Parliamentary Polling Polling Constituency Council Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthur's Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A02 A2 Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthur's Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A04 A4 Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Central Benwell and B01 B1 Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Central Benwell and B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 Propose no change to polling district or -

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthurs Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A02 A2 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthurs Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A04 A4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Benwell and Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding Central B01 B1 Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Benwell and Central B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 6SD Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Atkinson -

JLTC Playscript

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

Freeholders Benefit As Court Upholds Trust Decision

THE TRUST P u b l i s h e d b y t h e h a m P s t e a d G a r d e n s u b u r b t r u s t l i m i t e d Issue no. 10 sePtember 2012 Freeholders benefit as Court upholds Trust decision The Management Charge for the The Court ordered that the owner of The Court held that the Trust was financial year 2011/2012 has been 25 Ingram Avenue must pay the Trust’s acting in the public interest. The held steady at the same level as costs in defending, over a period of decision sets an important precedent the previous year – and there is a five years, a refusal of Trust consent for the future of the Scheme of further benefit for freeholders. for an extension. The Trust is in turn Management – and is doubly good passing the £140,000, recovered in news for charge payers. In August last year freeholders March 2012, back to charge payers. received a bill for £127. However, this THE GAZETTE AT A GLANCE year, owners of property that became The Court of Appeal ruled in freehold before 5 April 2008 will receive November 2011 that the Trust had Trust Decision Upheld ........................ 1 a bill for only £85 – thanks largely to been right to refuse consent for an Suburb Trees ........................................ 2 judges in the Court of Appeal. extension that would have encroached Hampstead Heritage Trail .................. 3 on the space between houses, Education ............................................. 5 The Hampstead contravened the Design Guidance and Garden Suburb Trust set an undesirable precedent across Trust Committees .............................. -

Issues and Options Topic Papers

Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Local Development Framework Joint Core Strategy and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document Issues and Options Topic Papers February 2012 Strategic Planning Tameside MBC Room 5.16, Council Offices Wellington Road Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DL Tel: 0161 342 3346 Email: [email protected] For a summary of this document in Gujurati, Bengali or Urdu please contact 0161 342 8355 It can also be provided in large print or audio formats Local Development Framework – Core Strategy Issues and Options Discussion Paper Topic Paper 1 – Housing 1.00 Background • Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) • Regional Spatial Strategy North West • Planning for Growth, March 2011 • Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) • Tameside Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) • Tameside Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2008 (SHMA) • Tameside Unitary Development Plan 2004 • Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 • Tameside Sustainable Community Strategy 2009-2019 • Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment • Tameside Residential Design Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 1.01 The Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 is underpinned by a range of studies and evidence based reports that have been produced to respond to housing need at a local level as well as reflecting the broader national and regional housing agenda. 2.00 National Policy 2.01 At the national level Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) sets out the planning policy framework for delivering the Government's housing objectives setting out policies, procedures and standards which Local Planning Authorities must adhere to and use to guide local policy and decisions. 2.02 The principle aim of PPS3 is to increase housing delivery through a more responsive approach to local land supply, supporting the Government’s goal to ensure that everyone has the opportunity of living in decent home, which they can afford, in a community where they want to live. -

Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This Page Intentionally Left Blank H6309-Prelims.Qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page Iii

H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page i Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This page intentionally left blank H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iii Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Editorial matter and selection Copyright © 2005, Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey. All rights reserved Individual contributions Copyright © 2005, the Contributors. All rights reserved No parts of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’. -

Capital Ring Section 11 Hendon Park to Highgate

Capital Ring Directions from Hendon Central station: From Hendon Central Station Section 11 turn left and walk along Queen’s Road. Cross the road opposite Hendon Park gates and enter the park. Follow the tarmac path down through the Hendon Park to Highgate park and then the grass between an avenue of magnificent London plane and other trees. At the path junction, turn left to join the main Capital Ring route. Version 2 : August 2010 Directions from Hendon Park: Walk through the park exiting left onto Shirehall Lane. Turn right along Shirehall Close and then left into Shirehall Start: Hendon Park (TQ234882) Park. Follow the road around the corner and turn right towards Brent Street. Cross Brent Street, turn right and then left along the North Circular road. Station: Hendon Central After 150m enter Brent Park down a steep slope. A Finish: Priory Gardens, Highgate (TQ287882) Station: Highgate The route now runs alongside the River Brent and runs parallel with the Distance: 6 miles (9.6 km) North Circular for about a mile. This was built in the 1920s and is considered the noisiest road in Britain. The lake in Brent Park was dug as a duck decoy to lure wildfowl for the table; the surrounding woodland is called Decoy Wood. Brent Park became a public park in 1934. Introduction: This walk passes through many green spaces and ancient woodlands on firm pavements and paths. Leave the park turning left into Bridge Lane, cross over and turn right before the bridge into Brookside Walk. The path might be muddy and slippery in The walk is mainly level but there some steep ups and downs and rough wet weather. -

2017 Annual Report Plc Redrow Sense of Wellbeing

Redrow plc Redrow Redrow plc Redrow House, St. David’s Park, Flintshire CH5 3RX 2017 Tel: 01244 520044 Fax: 01244 520720 ANNUAL REPORT Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 01 STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC REDROW ANNUAL REPORT 2017 A Better Highlights Way to Live £1,660m £315m 70.2p £1,382m £250m 55.4p £1,150m £204m 44.5p GOVERNANCE REPORT GOVERNANCE 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 £1,660m £315m 70.2p Revenue Profit before tax Earnings per share +20% +26% +27% 17p 5,416 £1,099m 4,716 £967m STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 4,022 10p £635m 6p 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 Contents 17p 5,416 £1,099m Dividend per share Legal completions (inc. JV) Order book (inc. JV) SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION SHAREHOLDER STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SHAREHOLDER 01 Highlights 61 Corporate Governance 108 Independent Auditors’ INFORMATION +70% +15% +14% 02 Our Investment Case Report Report 148 Corporate and 04 Our Strategy 62 Board of Directors 114 Consolidated Income Shareholder Statement Information 06 Our Business Model 68 Audit Committee Report 114 Statement of 149 Five Year Summary 08 A Better Way… 72 Nomination Committee Report Comprehensive Income 16 Our Markets 74 Sustainability 115 Balance Sheets Award highlights 20 Chairman’s Statement Committee Report 116 Statement of Changes 22 Chief Executive’s 76 Directors’ Remuneration in Equity Review Report 117 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Operating Review 98 Directors’ Report 118 Accounting Policies 48 Financial Review 104 Statement of Directors’ 123 Notes to the Financial 52 Risk -

S124 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S124 bus time schedule & line map S124 Kingston Park View In Website Mode The S124 bus line Kingston Park has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kingston Park: 3:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S124 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S124 bus arriving. Direction: Kingston Park S124 bus Time Schedule 12 stops Kingston Park Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Kenton School, North Kenton Tuesday Not Operational Kenton Lane-Moor Lane, Kenton Bar Wednesday Not Operational Kenton Lane - Ashover Road, Kenton Bar Thursday Not Operational Ponteland Road - St Buryan Crescent, Kenton Bar Friday 3:10 PM Ponteland Road, Newcastle Upon Tyne Saturday Not Operational Tudor Way-Blackheath Court, Kingston Park Blackheath Court, Newcastle Upon Tyne Tudor Way-Sheen Court, Kingston Park Tudor Way, Newcastle Upon Tyne S124 bus Info Direction: Kingston Park Tudor Way-Wilmington Close, Kingston Park Stops: 12 Tudor Way, Newcastle Upon Tyne Trip Duration: 15 min Line Summary: Kenton School, North Kenton, Brunton Road-Teddington Close, Kingston Park Kenton Lane-Moor Lane, Kenton Bar, Kenton Lane - Ashover Road, Kenton Bar, Ponteland Road - St Windsor Way-Brunton Road, Kingston Park Buryan Crescent, Kenton Bar, Tudor Way-Blackheath Court, Kingston Park, Tudor Way-Sheen Court, Windsor Way-Hersham Close, Kingston Park Kingston Park, Tudor Way-Wilmington Close, Hersham Close, Newcastle Upon Tyne Kingston Park, Brunton Road-Teddington Close, Kingston Park, Windsor Way-Brunton Road, Windsor Way-Windsor Walk, Kingston Park Kingston Park, Windsor Way-Hersham Close, Windsor Way, Newcastle Upon Tyne Kingston Park, Windsor Way-Windsor Walk, Kingston Park, Windsor Way-Fawdon Walk, Kingston Park Windsor Way-Fawdon Walk, Kingston Park Pelham Court, Newcastle Upon Tyne S124 bus time schedules and route maps are available in an o«ine PDF at moovitapp.com. -

THE OVERHEATED ARC - a Critical Analysis of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford-Newbury “Growth Corridor”

THE OVERHEATED ARC - A Critical Analysis of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford-Newbury “Growth Corridor” Part 1 A report by Smart Growth UK FEBRUARY 2019 http://www.smartgrowthuk.org 0 Contents __________________________________________________________________________ Executive summary 3 1. Introduction 7 2. What they propose 10 3. The damage it would do 16 4. Transport implications 23 5. The evolution of a bad idea 30 6. An idea founded on sand 54 7. Conclusions 63 1 “The Brain Belt” [Stella Stafford] 2 Executive Summary __________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The so-called “Brain Belt” has been evolved by a small and unrepresentative clique in Whitehall and beyond, virtually without consultation. There has been little or no consideration of the huge environmental damage it would do or the loss of food production involved. Misleading claims have been made about it having the highest productivity or it being the centre of the knowledge economy yet no-one apparently has asked whether, if the Arc concept is a sound one, there are other places in the UK it could be applied more productively and less damagingly. What they propose The Arc has grown since its inception from the “blob on a map” proposed by the National Infrastructure Commission to five whole counties plus Peterborough and the ill-defined M4 and M11 corridors. The NIC grew from a plan to link Oxford and Cambridge by motorway, via the NIC’s plans for new settlements and a million sprawl homes, to the Government’s plan to turn England’s bread and vegetable basket into “a world-leading economic place”. A new motorway from Cambridge to Newbury is at the centre of the plan which also claims the long-hoped-for Oxford-Cambridge railway reopening as its own idea. -

Green Spaces . . . Using Planning

Green spaces . using planning Assessing local needs and standards Green spaces…your spaces Background paper: Green Spaces…using planning PARKS AND GREEN SPACES STRATEGY BACKGROUND PAPER GREEN SPACES…USING PLANNING: ASSESSING LOCAL NEEDS AND STANDARDS _____________________________________________________________ Green Spaces Strategy Team April 2004 City Design, Neighbourhood Services Newcastle City Council CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Planning Policy Guidance Note 17 3 National and Local Standards 4 Density and housing types in Newcastle 3 Newcastle’s people 6 Assessing Newcastle's Green Space Needs 7 Is Newcastle short of green space? 8 Identifying “surplus” green space 9 Recommendations Annexe A Current Local, Core Cities and Beacon Council standards ( Quantity of green space, distances to green spaces and quality) Annexe B English Nature's Accessible Natural Green Space standards Annexe C Sample Areas Analysis; Newcastle's house type, density and open space provision. Annexe D Surveys and research Annexe E References and acknowledgements 2 1 Introduction 1.1 We need to consider whether we need standards for green spaces in Newcastle. What sort of standards, and how to apply them. 1.2 Without standards there is no baseline against which provision can be measured. It is difficult to make a case against a proposal to build on or change the use of existing open space or a case for open space to be included in a development scheme if there are no clear and agreed standards. 1.3 Standards are used to define how much open space is needed, particularly when planning new developments. Local authority planning and leisure departments have developed standards of provision and these have been enshrined in policy and guidance documents.