GPA HRER May Company Laurel Plaza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Leadership

2018 Annual Report RISEON THE LEADERSHIP NATIONAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES James A. Miller Thomas Schumacher Matt Conover, Chair Bartlett Wealth Management, Principal and Disney Theatrical Group, President Chairman Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Cincinnati, OH Vice President of Disneyland Entertainment Deborah Voigt Award-winning opera soprano Anaheim, CA Megan Tulac Phillips Hunter Bell, Vice Chair McKinsey & Company, Head of Marketing and ADVISORY BOARD Communications, Enterprise Agility Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA Board of San Francisco, CA Sarah Jane Arnegger Directors iHeart Radio Broadway, Director New York, NY John Prignano New York, NY Debbie Hill, Secretary Music Theatre International, COO and Director of Education and Development Aretta Baumgartner Community Arts Initiatives, Founder and New York, NY Center for Puppetry Arts, Education Director Executive Director Atlanta, GA Cincinnati, OH Kim Rogers Dori Berinstein Alex Birsh Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Amateur Licensing Dramatic Forces, Producer Playbill, Vice President and Chief Digital Officer New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY J. Jason Daunter Mark Drum David Redman Scott Disney Theatrical Group, Director of Theatrical Production Stage Manager Actor, Arts Advocate, EdTA Volunteer Licensing New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY Debby Gibbs Nancy Aborn Duffy ETF Legacy Circle Committee, Chair Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Abbie Van Nostrand Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Client Tupelo, MS Company Owner Relations & Community Engagement New York, NY -

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Application for the FOREMAN & CLARK BUILDING

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC -200 8-4978 -HCM HEARING DATE: January 15, 2009 Location: 701 South Hill St. TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 9 PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Central City 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Downtown Los Angeles 90012 Legal Description: FR4 of Mueller Subdivision of the North ½ of Block 26 Ord’s Survey PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the FOREMAN & CLARK BUILDING REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Kyung Ku Cho c/o Young Ju Kwon APPLICANT: 3200 Wilshire Blvd. #1100 Los Angeles, CA 90010 OWNER’S Robert Chattel REPRESENTATIVE: Chattel Architecture, Planning, and Preservation 13417 Ventura Blvd. Sherman Oaks, CA 94123 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10(c)4 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal may warrant further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. S. GAIL GOLDBERG, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] ________________________ Edgar Garcia, Preservation Planner Office of Historic Resources Attachments: November, 2008 Historic-Cultural Monument Application ZIMAS Report 701 S. Hill Street. CHC-2008-4978-HCM Page 2 of 2 SUMMARY Built in 1929 and located in the downtown area, this 13-story commercial building exhibits character-defining features of Art Deco-Gothic architecture. -

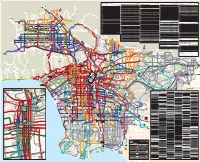

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

Mr. Gregory Michael Beaudet on August 27, 2009 by San Diego Police Officer Jared Ross Wilson; SDPD Case No

... I . San Diego JESUS RODRIGUEZ 330 West Broadway ASSlSTANT DISTRICT ATIURNEY THEDI·.:~:: ORNEY San Diego, CA 92101 CO~~ AN~bIEGO (619) 531-4040 , r/j "<' ..... \," BONNIE MJ bUMANIS http://www.sandiegoda.com DISTRICT ATTORNEY December 3, 2009 Chief William Lansdowne San Diego Police Department 1401 Broadway San Diego, CA 92101 Re: Fatal shooting of Mr. Gregory Michael Beaudet on August 27, 2009 by San Diego Police Officer Jared Ross Wilson; SDPD Case No. 09-044849; DA Special Operations Case No. 09-167PS; Deputy District Attorney Assigned: Damon Mosler Dear Chief Lansdowne: We've reviewed the reports and other materials compiled by your department's Homicide Division concerning the fatal shooting of Mr. Gregory Beaudet by Officer Jared Wilson on August 27,2009. A District Attorney Investigator responded to the scene and was briefed by your investigators. This case was presented to the DA's Office for review on November 19,2009. Persons Involved Mr. Gregory Beaudet was 22 years-old, homeless and was armed with an eight-inch knife with a four-inch double edged blade. Officer Jared Wilson was in full uniform and assigned to bicycle patrol duties in Central Division. He was armed with a Heckler & Kock .45 caliber semi-automatic pistol. Background Shortly before midnight on Thursday, August 27,2009, Mr. Beaudet along with two other men entered the Ralphs Grocery Store at 101 G Street in San Diego. The first man stole a bottle of liquor, ran from the store and eluded capture. Security guards and store employees chased after the thief, but they couldn't catch him because their path was blocked by Mr. -

Update on Acquisition of Permanent Subsurface Easements Through The

June 13, 1995 Los Angeles County TO: BOARD OF DIRECTORS Metropolitan Transportation THROUGH: Authority FROM: 425 South Main Street SUBJECT: UPDATE ON ACQUISITION OF PERMANENT Los Angeles, CA SUBSURFACE EASEMENTS THROUGH THE 9oo~3q393 HOLLYWOODHILLS 213.972.6ooo BACKGROUND At its May24, 1995 meeting, the MTABoard of Directors was requested to hold a public hearing and adopt a Resolution of Necessity authorizing the commencementof eminent domain proceedings to acquire permanent subsurface easements (PSE) from approximately84 properties. The properties are located in the HollywoodHills along the alignment of the Metro Rail Segment 3 tunnel alignment between the Hollywood/Highlandand Universal City stations. Approximately 30 property owners were present at the meeting and addressed the Board concerning the staffs request to initiate condemnation action. The Board deferred any action on the adoption of the resolution for 30 days and requested staff to work with the property ownersduring the 30 days and report back to the Board on all actions taken. ACTIONS TAKEN SUBSEQUENT TO BOARD MEETING The Real Estate, Construction and Public Affairs staffs immediately made plans to hold a communitymeeting with the property owners to discuss the project and to respond to all questions raised by the property owners. A meeting was held on Wednesday, May31, at the CampoDe Cahuenga in Studio City. A meeting notice was sent to all property owner notifying them of the meeting. Approximately 35 property owners attended the meeting. Staff members from Real Estate, Construction and County Counsel made presentations and answered questions raised by the property owners. A written response to frequently asked Real Estate questions was prepared as a hand-out and was distributed at the meeting (Attachment 1). -

IV. Environmental Impact Analysis D.1 Cultural Resources—Historic Resources

IV. Environmental Impact Analysis D.1 Cultural Resources—Historic Resources 1. Introduction The following section of the Draft EIR evaluates potential impacts related to historic resources associated with development of the Proposed Project. The analysis is based on the following study and correspondence: Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza Historic Resource Report (the “Historic Resource Report”) prepared by Christopher A. Joseph and Associates, July 2009 (Appendix D1 to this Draft EIR) and written correspondence from the South Central Coastal Information Center at California State University, Fullerton, on April 16, 2009 (Appendix D2 to this Draft EIR). 2. Environmental Setting Generally, a lead agency must consider a property a historic resource under CEQA if it is eligible for listing in the National or California Register of Historical Resources (the “California Register”). The California Register is modeled after the National Register of Historic Places (the “National Register”). Furthermore, a property is presumed to be historically significant if it is listed in a local register of historic resources or has been identified as historically significant in a historic resources survey (provided certain criteria and requirements are satisfied) unless a preponderance of evidence demonstrates that the property is not historically or culturally significant.1 The National and California Register designation programs are discussed below. In addition, the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Ordinance is discussed as a potentially applicable local designation program. a. Regulatory Framework (1) Federal Level (a) National Register of Historic Places The National Historic Preservation Act established the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) to recognize resources associated with the country’s history and heritage. -

Hollywood Studio Magazine (September 1971)

1 ^Hoilyw/dod 1 ( 3 ■ si i lr*i IO cTWagaziqe , | SEPTEMBER 1971/ 50 CENTS — \ Computer ItCJl Crafted Color "SHIRT CLUB" Customer's Mr. fjy f?ashiOH 1 Jw JLwduf IStL 12 o 19837 Ventura Blvd., Woodland Hills, Calif. 1 1 L Phone 883-7010 1 1 3 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8]~9 10 NO DOWN Low monthly payments Another Don Ray OVER TV Super Special 300© Still $24500 VOGUE MODEL EP 402 STOCK! 14 INCH DIAGONAL 18 INCH DIAGONAL PORTABLE... $295. “More for your shirt purchasing dollar” If you want affordable Color TV (and who doesn't), the Vogue is just what the budget MICKEY RICH’S ordered. And it's portable. Weighs less than 40 lbs., so it's handy to carry anywhere. Attractive vinyl finish is tough, “SHIRTS GALORE* yet cleans easily with a damp cloth. Built-in 19837 Ventura Blvd., Woodland Hills VHF and UHF antennas give you true Phone 883-7010 on-the-move Color TV. The Vogue is fun to own. And for that matter, easy to own too. OPEN MON. THRU FRI. 10-9-SAT. 9-6 Plastic cabinet finished in : Moonmist Gold vinyl/Mist White ALL MAJOR CREDIT CARDS WELCOMED Special Consideration to Studio Employees 21 YEARS DEPENDABLE SERVICE • Double Knits • Walace Beeny Look . Nostalgic Look • "Shirts by Joel" Kennington Ltd. DON RAY • All Styles Galore • All Sizes Galore AND APPLIANCES • Dress Shirts Galore ■■■HaBankamerica . Easy Financings* • All Name Brands Poplar 3-9431 TR 7-4692 4257 LANKERSHIM BLVD. ALL NEW GIGANTIC SELECTION OF X NORTH HOLLYWOOD / JEANS & DOUBLE KNIT PANTS Executives cTTTagaziqe swear by it SEPTEMBER 1971 Volume 6 No. -

RSU 22 Voters Approve 2017-18 Budget with Increased State Subsidy

August 2017 • Link-22 • RSU 22POSTAL - Hampden-Newburgh-Winterport-Frankfort PATRON ECRWSS • Page 1 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID HAMPDEN, ME PERMIT NO. 2 RSU 22 • Hampden • Newburgh • Winterport • Frankfort 24 Main Road North, Hampden, ME 04444 August 2017 HA recognized at National JCL convention RSU 22 voters approve The Junior Classical League 2017-18 budget with (JCL) of Hamp- den Academy increased state subsidy received sev- eral honors at in August 1 referendum the National RSU 22 voters have approved the 2017-18 budget at the dis- JCL convention, trict Budget Validation Referendum on Tuesday, August 1. which was held The vote was 397 for the budget and 328 against. July 24-29 at Voters in all four RSU 22 communities supported the budget. Troy University The vote tallies were: Hampden, 249-230; Newburgh, 47-24; Win- in Troy, AL. terport, 84-68; and Frankfort, 17-6. Five Hampden The second referendum was needed because voters rejected Academy students the original 2017-18 budget at the first referendum on June 13, attended the con- 710 to 637. vention, including Hampden Academy Junior Classical League representatives at the Na- The original budget was published and approved at the Dis- Andrew Terry, trict Budget Meeting before the Legislature had approved its fi- Molly Swalec, tional JCL Convention—Front row (l. to r.): Audrie French, Noah Burby, and Aidan Babbitt. Back row: Molly Swalec, faculty advisor Ben John- nal appropriations for school funding. The original RSU 22 bud- Audrie French, son, and Andrew Terry. get included only $18.1 million in state subsidy; the final RSU 22 Noah Burby, and subsidy figure was $18.7 million, an increase of $566,000. -

San Francisco, California

Compressed Area - 4.5 Miles 2.5 Miles B C D E F G H J K L M N P Q R Blue & Gold Golden Gate Fort Point Blue & Gold San Francisco Bay Red & Fleet to Fleet to Vallejo, Cable Car Route Bridge White Fleet Angel Island Jack London Square 1 San Francisco, California USA San Francisco Bay Cruise & Oakland 1 (toll south Sausalito & and Bay Cruise Street Car (F-Line) bound) Maritime Tiburon Golden Gate National Recreation Area Alcatraz Ferry Service MasonCrissy St Field National PIER Historical Park 45 43 41 39 One Way Traffic 47 431/2 Pre Marina Green s Hyde St id l io Aquatic 35 End of One Way Traffic l Pa rkwa Marina Blvd Pier d y e Lin Park v co l Cervantes Blvd Cruise Ship w Direction of The Walt l o n B MARINA Fort Mason Jefferson St Terminal Disney Highway Ramps D The B n Family 2 l E 33 2 c Anchorage m l Cannery FISHERMANS o Museum Photo Vantage Points v ba M c Beach St (Main Post) d Palace Beach St rc n a Ghirardelli & Scenic Views i WHARF d Baker of Fine Arts 31 L e GGNRA Square North Point St ro BART Station Beach North Point St Headquarters Shopping Complexes t S Bay St Bay St Bay St ra Pier 29 Parks mb R Alha Moscone Francisco St Francisco St 3 Beaches Letterman i Lincoln Blvd c THE 3 h Rec Ctr Veterans Blvd Digital Arts a Chestnut St Points of Interest Center Ave r Chestnut St TELEGRAPH EMBARCADERO ds HILL o “Crookedest 23 Hospitals n d Lombard St Gen. -

V. Prince George's County Retail Maps

M-NCPPC LIST OF EXHIBITS I. EXISTING RETAIL PERFORMANCE Exhibit I-1 Historical Inventory by Type of Retail; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-2 Historical Absorption by Type of Retail; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-3 Historical Deliveries by Type of Retail; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-4 Historical Vacancy by Type of Retail; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-5 Major Shopping Center Openings and Absorption Pace; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-6 Super Regional/Regional Malls, Lifestyle, And Power Center Retail Occupancy Rate; Prince George’s County, MD; Washington, D.C., MSA; And Baltimore MSA; 2011-2014 QTD Exhibit I-7 Community And Neighborhood/Strip Center Retail Occupancy Rate; Prince George’s County, MD; Washington, D.C., MSA; And Baltimore MSA; 2011-2014 QTD Exhibit I-8 Super Regional/Regional Malls, Lifestyle, And Power Center Absorption as Percent of Occupied Space; Prince George’s County, MD; Washington, D.C., MSA; And Baltimore MSA; 2011-2014 QTD Exhibit I-9 Community And Neighborhood/Strip Center Absorption as Percent of Occupied Space; Prince George’s County, MD; Washington, D.C., MSA; And Baltimore MSA; 2011-2014 QTD Exhibit I-10 Super Regional and Regional Mall Locations and Current Property Statistics; Prince George’s County, MD; 2014 Exhibit I-11 Super Regional and Regional Malls - Inventory and Average Rental Rate; Prince George’s County, MD; 2006-2014 QTD Exhibit I-12 Super Regional and Regional Malls - Absorption, Deliveries, -

Metro Public Hearing Pamphlet

Proposed Service Changes Metro will hold a series of six virtual on proposed major service changes to public hearings beginning Wednesday, Metro’s bus service. Approved changes August 19 through Thursday, August 27, will become effective December 2020 2020 to receive community input or later. How to Participate By Phone: Other Ways to Comment: Members of the public can call Comments sent via U.S Mail should be addressed to: 877.422.8614 Metro Service Planning & Development and enter the corresponding extension to listen Attn: NextGen Bus Plan Proposed to the proceedings or to submit comments by phone in their preferred language (from the time Service Changes each hearing starts until it concludes). Audio and 1 Gateway Plaza, 99-7-1 comment lines with live translations in Mandarin, Los Angeles, CA 90012-2932 Spanish, and Russian will be available as listed. Callers to the comment line will be able to listen Comments must be postmarked by midnight, to the proceedings while they wait for their turn Thursday, August 27, 2020. Only comments to submit comments via phone. Audio lines received via the comment links in the agendas are available to listen to the hearings without will be read during each hearing. being called on to provide live public comment Comments via e-mail should be addressed to: via phone. [email protected] Online: Attn: “NextGen Bus Plan Submit your comments online via the Public Proposed Service Changes” Hearing Agendas. Agendas will be posted at metro.net/about/board/agenda Facsimiles should be addressed as above and sent to: at least 72 hours in advance of each hearing.