Document Resume Ed 355 347 Ce 063 008 Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

Christina Yahn William Yahn Louise A. Yeaton Charles Ylonen -Z- Joyce L

1 Care Dimensions Tree of Lights 2019 Honor Roll Book 2 -A- Phyllis Abare Sidney Abare Walter L. Abel Sidney N. Abramson George W. Accomando Charles Quincy Adams Phyllis Humphrey Adams Randy Adams Christos Agganis Jack and Jayne Ahern Patricia Akowicz Margaret and Orville Alexander Dr. Robert (Buck) Alexander All Family Members 3 Janet and Harry Allaby Abner L. Allen Mr. and Mrs. C. Clifford Allen, Jr. Lucille "Mem" Allen Sally Allphin Carol T. Alpers Phineas Alpers Carol A. Alway Eleanor Ammen Arlene Anderson Bernice Anderson David W. Anderson Dorothy Ann Anderson Edward Anderson Edward H. Anderson 4 Kenneth Anderson Maureen Anderson Morgan Rochelle Anderson Clarice P. Andrews Joseph F. Andrews Michael Andrews Peter E. Andrews Alphonse W. Angelli Maureen Annese-Picard Angelina Antczak Alice Armentrout Richard E. “Dick” Ash Bernard Charles Atkinson Bert and Rita Aube, El Silva, James Wilson, Sr. John and Mary Aulson 5 Lewis Austin Teresa Autuori Maria Azevedo -B- Eric Baade Leo, Dorothy and Dan Bachini Martin Badger Jean Bailey Dr. William E. Bailey Phyllis Baker Louis Balestraci Louis J. Balestraci M. Helen Balestraci Sandra Ball Beverly P. Barber 6 Rev. Robert H. and Mrs. Ruth L. Barber Samuel C. Barchus Sybil Barnard Donald R. Barnett, Jr. Donald R. Barnett, Sr. Theresa Barnett Domenic Barrasso Mr. and Mrs. Allan Barratt Dana R. Barratt Melissa S. Barrowclough Michael J. Barry Palmina "Pam" Barry Robert J. Barry W. Dana Bartlett 7 Mary Ellen and Wilbur Bassett, Sr. Captain Raymond H. Bates Peter W. Beacham Charley Rose Beasley Phyllis Beaulieu Cynthia K. Bedard Gertrude (Blue) Bee Mildred Begin Theresa and John Bekeritis Lianne Belkas George Bellevue Richard Bellitti Teresa Bello A. -

Class of 1965 50Th Reunion

CLASS OF 1965 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1965 Abby Goldstein Arato* June Caudle Davenport Anna Coffey Harrington Catherine Posselt Bachrach Margo Baumgarten Davis Sandol Sturges Harsch Cynthia Rodriguez Badendyck Michele DeAngelis Joann Hirschorn Harte Isabella Holden Bates Liuda Dovydenas Sophia Healy Helen Eggleston Bellas Marilyn Kirshner Draper Marcia Heiman Deborah Kasin Benz Polly Burr Drinkwater Hope Norris Hendrickson Roberta Elzey Berke Bonnie Dyer-Bennet Suzanne Robertson Henroid Jill (Elizabeth) Underwood Diane Globus Edington Carol Hickler Bertrand* Wendy Erdman-Surlea Judith Henning Hoopes* Stephen Bick Timothy Caroline Tupling Evans Carla Otten Hosford Roberta Robbins Bickford Rima Gitlin Faber Inez Ingle Deborah Rubin Bluestein Joy Bacon Friedman Carole Irby Ruth Jacobs Boody Lisa (Elizabeth) Gallatin Nina Levin Jalladeau Elizabeth Boulware* Ehrenkranz Stephanie Stouffer Kahn Renee Engel Bowen* Alice Ruby Germond Lorna (Miriam) Katz-Lawson Linda Bratton Judith Hyde Gessel Jan Tupper Kearney Mary Okie Brown Lynne Coleman Gevirtz Mary Kelley Patsy Burns* Barbara Glasser Cynthia Keyworth Charles Caffall* Martha Hollins Gold* Wendy Slote Kleinbaum Donna Maxfield Chimera Joan Golden-Alexis Anne Boyd Kraig Moss Cohen Sheila Diamond Goodwin Edith Anderson Kraysler Jane McCormick Cowgill Susan Hadary Marjorie La Rowe Susan Crile Bay (Elizabeth) Hallowell Barbara Kent Lawrence Tina Croll Lynne Tishman Handler Stephanie LeVanda Lipsky 50TH REUNION CLASS OF 1965 1 Eliza Wood Livingston Deborah Rankin* Derwin Stevens* Isabella Holden Bates Caryn Levy Magid Tonia Noell Roberts Annette Adams Stuart 2 Masconomo Street Nancy Marshall Rosalind Robinson Joyce Sunila Manchester, MA 01944 978-526-1443 Carol Lee Metzger Lois Banulis Rogers Maria Taranto [email protected] Melissa Saltman Meyer* Ruth Grunzweig Roth Susan Tarlov I had heard about Bennington all my life, as my mother was in the third Dorothy Minshall Miller Gail Mayer Rubino Meredith Leavitt Teare* graduating class. -

Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise and Public Sectors Who Are Considering Investing Resources in Early Childhood Programs

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Labor and Population View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Early Childhood Interventions Proven Results, Future Promise Lynn A. Karoly M. Rebecca Kilburn, Jill S. Cannon Prepared for The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. The research described in the report was conducted for The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. by RAND Labor and Population, a division of the RAND Corporation. -

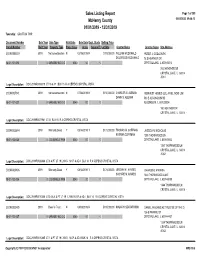

Sales Report

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 309 McHenry County 05/04/2020 09:46:13 01/01/2019 - 12/31/2019 Township: GRAFTON TWP Document Number Sale Year Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Parcel Number Built Year Property Type Prop. Class Acres Square Ft. Lot Size Grantor Name Grantee Name Site Address 2019R0006019 2019 Not advertised on mN 02/19/2019 N $115,000.00 WILLIAM MCDONALD PETER J. GODLEWSKI DOLORESS MCDONALD 78 S HEATHER DR 18-01-101-013 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145018 78 S HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5018 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0006019 LT 16 & 17 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0027941 2019 Not advertised on mN 07/08/2019 N $150,000.00 CHARLES G. ALEMAN REINVEST HOMES LLC, AN ILLINOIS LIMIT DAWN S. ALEMAN 503 E ALGONQUIN RD 18-01-101-027 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 ALGONQUIN, IL 601023004 160 HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 - Legal Description: DOC 2019R0027941 LT 31 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0026844 2019 Warranty Deed Y 08/14/2019 Y $172,000.00 THOMAS M. COFFMAN JESSICA N. NICHOLAS KATRINA COFFMAN 1350 THORNWOOD LN 18-01-102-035 0 LDG SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145042 1350 THORNWOOD LN CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5042 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0026844 LT 6 & PT LT 19 LYING N OF & ADJ BLK 14 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0010406 2019 Warranty Deed Y 04/12/2019 Y $174,000.00 JEREMY M. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

An Interview with LINA SHARP

An Interview with LINA SHARP An Oral History conducted and edited by Robert D. McCracken Nye County Board of Commissioners Nye County, Nevada Tonopah 1992 COPYRIGHT 1992 Nye County Town History Project Nye County Commissioners Tonopah, Nevada 89049 Lina Pinjuv Sharp, Blue Eagle Ranch, Railroad Valley, NV 1941 Jim Sharp, Blue Eagle Ranch, Railroad Valley, NV, 1941 CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments Introduction CHAPTER ONE Lina discusses her parents, Ivan and Anna Lalich Pinjuv, who both came to the U.S. from Yugoslavia; Lina's childhood and youth in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, including memories of the Mikulich family and of a hospital stay where Lina experienced Las Vegas's first air conditioning; Lina's college years in Reno and her first teaching assignment — at the Blue Eagle Ranch; a discussion of the Bordoli family and the Bordoli Ranch; Lina recalls Mary McCann Sharp; the children Lina taught at Blue Eagle. CHAPTER TWO Lina's first year teaching at Blue Eagle; the name Blue Eagle; Lina marries Jim Sharp and becomes a permanent resident of Railroad Valley; the Sharp family's progenitor, Henry Sharp, and his son George (Lina's father-in-law); the route of the Midland Trail, which passed through the Blue Eagle Ranch; some history of the communities near Blue Eagle — Nyala, Troy, Grant, and Irwin canyons; George Sharp purchases Blue Eagle and meets his future bride, Mary- McCann; McCann Station between Hot Creek and Tybo. CHAPTER THREE George and Mary McCann Sharp spend some years in Belmont, then return to Blue Eagle; the children and grandchildren of George and Mary; the Sharps's Blue Eagle Ranch and its grazing land; Lina recalls the Blue Eagle Ranch as it was in 1940; federal government interference at Blue Eagle; drilling for potash near Blue Eagle and finding water; the Locke Ranch; Emery Garrett of Nyala and Currant Creek; some history on Nyala. -

Search the List of Unclaimed Child Support

UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530. LAST NAME FIRST NAME MI ADDRESS CITY ABADIA CARMEN Y HOUSE A4 CEIBA ABARCA PAULA 7122 W OKANOGAN PLACE BLDG A KENNEWICK ABBOTT DONALD W 11600 ADENMOOR AVE DOWNEY ABERNATHY JACQUELINE 7722 W CONGRESS MILWAUKEE ABRAHAM PATRICIA 875 MILWAUKEE RD BELOIT ABREGO GERARDO A 1741 S 32ND ST MILWAUKEE ABUTIN MARY ANN P 1124 GRAND AVE WAUKEGAN ACATITLA JESUS 925 S 14TH ST SHEBOYGAN ACEVEDO ANIBAL 1409 POSEY AVE BESSEMER ACEVEDO MARIA G 1702 W FOREST HOME AVE MILWAUKEE ACEVEDO-VELAZQUEZ HUGO 119 S FRONT ST DORCHESTER ACKERMAN DIANE G 1939 N PORT WASHINGTON RD GRAFTON ACKERSON SHIRLEY K ADDRESS UNKNOWN MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CELIA C 5812 W MITCHELL ST MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CHRISTIAN 1842 ELDORADO DR APT 2 GREEN BAY ACOSTA JOE E 2820 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ACUNA ADRIAN R 2804 DUBARRY DR GAUTIER ADAMS ALIDA 4504 W 27TH AVE PINE BLUFF ADAMS EDIE 1915A N 21ST ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS EDWARD J 817 MELVIN AVE RACINE ADAMS GREGORY 7145 BENNETT AVE S CHICAGO ADAMS JAMES 3306 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS LINDA F 1945 LOCKPORT ST NIAGARA FALLS ADAMS MARNEAN 3641 N 3RD ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS NATHAN 323 LAWN ST HARTLAND ADAMS RUDOLPH PO BOX 200 FOX LAKE ADAMS TRACEY 104 WILDWOOD TER KOSCIUSKO ADAMS TRACEY 137 CONNER RD KOSCIUSKO ADAMS VIOLA K 2465 N 8TH ST LOWER MILWAUKEE ADCOCK MICHAEL D 1340 22ND AVE S #12 WIS RAPIDS ADKISSON PATRICIA L 1325 W WILSON AVE APT 1206 CHICAGO AGEE PHYLLIS N 2841 W HIGHLAND BLVD MILWAUKEE AGRON ANGEL M 3141 S 48TH ST MILWAUKEE AGUILAR GALINDO MAURICIO 110 A INDUSTRIAL DR BEAVER DAM AGUILAR SOLORZANO DARWIN A 113 MAIN ST CASCO AGUSTIN-LOPEZ LORENZO 1109A S 26TH ST MANITOWOC AKBAR THELMA M ADDRESS UNKNOWN JEFFERSON CITY ALANIS-LUNA MARIA M 2515 S 6TH STREET MILWAUKEE ALBAO LORALEI 11040 W WILDWOOD LN WEST ALLIS ALBERT (PAULIN) SHARON 5645 REGENCY HILLS DRIVE MOUNT PLEASANT ALBINO NORMA I 1710 S CHURCH ST #2 ALLENTOWN Page 1 of 138 UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530. -

Citizen Participation in Planning: Selected Interdisciplinary Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 628 EA 007 064 AUTHOR Booher, David E. TITLE Citizen Participation in Planning: Selected Interdisciplinary Bibliography. Exchange Bibliography No. 718. INSTITUTION Council of Planning Librarians, Monticello, Ill. PUB DATE Jan 75 NOTE 22p.; Exchange Bibliography No. 718 AVAILABLE FROM Council of Planning Librarians, P. O. Box 229, Monticello, Illinois 61856 ($2.00) EDES PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Bibliographies; *Citizen Participation; *Interdisciplinary Approach; *Planning; *Public Policy ABSTRACT This bibliography is an inventory of relevant materials in planning and related disciplines. It draws on research and theoretical perspectives from planning literature, economics, political science, psychology, public administration, and sociology. Section one suggests references that offer general and theoretical perspectives useful in the development of research frameworks. Section two contains selected references to empirical research and case studies that may provide useful background. Section threelists references that focus on research in other countries. (Author /MLF) Council of Planning LibrariansEXCHANGE BIBLIOGRAPHY January 1975 1-.14 TV. NT OF HEALTH CNd WELFARE iNS7ITUTE OF 718 ,t.CATION iK. 41 P640 .41 CITIZEN PARTICI!'ATION IN PLANNING: SelectedInterdisciplinary Bibliography David E. Booher Research Center, Graduate School of Planning University of Tennessee Mrs. Mary Vance, Editor Post Office Box 229 Monticello, Illinois 61856 LI:chant,e Libliography I PL.1'1,111TG: .33LECT.,D LIZLIOGRk_PHY by David E. Booher Research Center Graduate Schodl of Planning University of Tennessee LYqppucricg. Citizen involvement in public policy formation has been a topic of concern in scholarly research since political theorists turned their attention to it in earliercenturies. hore recently, citizen participation has becamea topic of interest not only for academicians but for public policy practioners as well. -

List of Participants

List of Participants SURNAME FIRST NAME Country SURNAME FIRST NAME Country AALBERGSJØ SIV G. Norway AMON HEIDEMARIE Austria ABRAHAMS IAN United Kingdom AMOS RUTH United Kingdom ABRAHAMSSON CRISTIAN Sweden AMPATZIDIS GEORGIOS Greece ABRAMOVICH ANAT Israel AMPRAZIS ALEXANDROS Greece ABRIL-GALLEGO ANA MARÍA Spain ANASTÁCIO ZÉLIA Portugal ACEBAL EXPOSITO MARIA DEL CARMEN Spain ANDERSEN TRINE HØJBERG Norway ACHIAM MARIANNE Denmark ANDERSON DAYLE New Zealand ACOSTA GARCIA KATHERINE Chile ANDERSON TREVOR United States ACUNA CLAUDIA Netherlands ANDERSSON JAN Sweden ADADAN EMINE Turkey ANDERSSON KRISTINA Sweden ADAMS JENNIFER Canada ANDRÉE MARIA Sweden ADBO KARINA Sweden ANJOU CLAIRE France ADÚRIZ-BRAVO AGUSTÍN Argentina ANTINK-MEYER ALLISON United States AGADI DINA Israel ANWAR TASNEEM Pakistan AGEN FEDERICO Spain ARANDA GEORGE Australia AGUIRRE-MUNOZ ZENAIDA United States ARAUJO CARLA Brazil ÅHMAN NICLAS Sweden ARAUJO CASTRO PABLO MICAEL Brazil AHRENKIEL LINDA Denmark ARCHER LOUISE United Kingdom AHUMADA GERMAN Chile ARNOLD JULIA Switzerland AINI RAHMI QUROTA Korea Republic of ARVOLA ORLANDER AULI Sweden AIREY JOHN Sweden ASAHINA SHOTA Japan AIVELO TUOMAS Finland ASAKLE SHADI Israel AKAYGUN SEVIL Turkey ASH DORIS United States AKERSON VALARIE United States ASSAAD YAMMINE Lebanon ÅKESSON NILSSON GUNILLA Sweden ASTON KATHERINE United Kingdom AKINYEMI OLUTOSIN SOLOMON South Africa ASTROM MARIA Sweden AKIRI EFFRAT Israel ATANASOVA SANJA Switzerland AKMAN PERIHAN Germany ATKINS ELLIOTT LESLIE United States AKSOZ BUSRA Turkey ATWATER MARY M United States ALAKOYUN LEMAN Turkey AUCLAIR ALEXANDRA Canada ALARCÓN-OROZCO Mª MARTA Spain AUNING CLAUS Denmark ALINA BEHRENDT Germany AVRAAMIDOU LUCY Netherlands ALLAIRE-DUQUETTE GENEVIEVE Israel AVSAR ERUMIT BANU Turkey ALMEIDA ANTÓNIO Portugal AZAM SAIQA Canada ALMSTRUP CHRISTINE Denmark BABAI REUVEN Israel ALMUKHAMBETOVA AINUR Kazakhstan BACCAGLINI-FRANK ANNA Italy ALONZO ALICIA United States BÄCHTOLD MANUEL France ALSOP STEVE Canada BACKHOUSE ANITA United Kingdom AMARAL EDENIA M. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Gianmarco Ireo Paolo OTTAVIANO Born in Milan (Italy) on Sept.29,1967. Italian citizenship. Professional address: London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Economics and Centre for Economic Performance Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20-7955 6856. Fax: +44(0)20-7955 7595. E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.lse.ac.uk/researchAndExpertise/Experts/profile.aspx?KeyValue=g.i.ottaviano@ls e.ac.uk CURRENT POSITIONS Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK. Honorary Professor of Economics (Studioso di chiara fama), Department of Economics, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy. Director of the Globalisation Programme, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK. Senior Non-Resident Fellow, Bruegel, Brussels, Belgium. Research Fellow, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), International Trade Programme, London, U.K. Research Fellow, Center for Financial Studies (CFS), Frankfurt, Germany. Research Fellow, Fondazione ENI Enrico Mattei (FEEM), Milan, Italy. Research Fellow, Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IFW), Kiel, Germany. Research Affiliate, Institut de Analisi Economica, C.S.I.C., Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain. External Research Fellow, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), University College London, U.K. External Fellow, Leverhulme Centre for Research on Globalisation and Economic Policy (GEP), University of Nottingham, U.K. 1 PAST POSITIONS 2008-2013. Full Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy. Taught courses: International Economics, Macroeconomics. 2009-2011. Coordinator of the PhD Degree Program in Economics. 2011-2013. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL