Pdf, Accessed 20 July 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It's Not Rocket Science

It's Not Rocket Science ... Oh. Wait. By Karen Green Wednesday October 5, 2011 06:00:00 am Our columnists are independent writers who choose subjects and write without editorial input from comiXology. The opinions expressed are the columnist's, and do not represent the opinion of comiXology. Full disclosure: I'm a bit of a procrastinator. The good folks at ComiXology who post these columns know this all too well, as I inevitably submit my work about 24 hours before it's supposed to run, as opposed to the five days specified in my contract (sorry, Peter!). And this column you're reading now was planned, oh, back in early July, then postponed until late September for promotional purposes, and now I'm writing it at the last minute (as usual) and most of what I'd planned to say is lost, lost in the mists of memory. Here's the scoop: I had the privilege of interviewing author Jim Ottaviani on the Graphic Novels Stage at the 2011 American Library Association meeting in New Orleans this past June. I was too caught up in the moment to take notes on all his answers, though, and I thought, "Oh, I'll ask him all this again via email." Erm… Then I thought—oh, I know: Jim is going to come talk at Columbia in October! I'll wait and write this column as a publicity device, giving me plenty of time to get in touch with him for background before then. Erm…. So, now, Ottaviani will be here at Columbia on Friday October 7 and there is no time to check back in with him, as he is on his whirlwind book tour, taking him to such Sacred Haunts of Science as MIT and the Los Alamos National Laboratory. -

Zines and Minicomics Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c85t3pmt No online items Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection Finding Aid Authors: Anna Culbertson and Adam Burkhart. © Copyright 2014 Special Collections & University Archives. All rights reserved. 2014-05-01 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Guide to the Zines and MS-0278 1 Minicomics Collection Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection 1985 Special Collections & University Archives Overview of the Collection Collection Title: Zines and Minicomics Collection Dates: 1985- Bulk Dates: 1995- Identification: MS-0278 Physical Description: 42.25 linear ft Language of Materials: EnglishSpanish;Castilian Repository: Special Collections & University Archives 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Access Terms This Collection is indexed under the following controlled access subject terms. Topical Term: American poetry--20th century Anarchism Comic books, strips, etc. Feminism Gender Music Politics Popular culture Riot grrrl movement Riot grrrl movement--Periodicals Self-care, Health Transgender people Women Young women Accruals: 2002-present Conditions Governing Use: The copyright interests in these materials have not been transferred to San Diego State University. Copyright resides with the creators of materials contained in the collection or their heirs. The nature of historical archival and manuscript collections is such that copyright status may be difficult or even impossible to determine. Requests for permission to publish must be submitted to the Head of Special Collections, San Diego State University, Library and Information Access. -

Alternative Comics: an Emerging Literature

ALTERNATIVE COMICS Gilbert Hernandez, “Venus Tells It Like It Is!” Luba in America 167 (excerpt). © 2001 Gilbert Hernandez. Used with permission. ALTERNATIVE COMICS AN EMERGING LITERATURE Charles Hatfield UNIVERSITY PRESS OF MISSISSIPPI • JACKSON www.upress.state.ms.us The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Copyright © 2005 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First edition 2005 ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hatfield, Charles, 1965– Alternative comics : an emerging literature / Charles Hatfield. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57806-718-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57806-719-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Underground comic books, strips, etc.—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN6725.H39 2005 741.5'0973—dc22 2004025709 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix Alternative Comics as an Emerging Literature 1 Comix, Comic Shops, and the Rise of 3 Alternative Comics, Post 1968 2 An Art of Tensions 32 The Otherness of Comics Reading 3 A Broader Canvas: Gilbert Hernandez’s Heartbreak Soup 68 4 “I made that whole thing up!” 108 The Problem of Authenticity in Autobiographical Comics 5 Irony and Self-Reflexivity in Autobiographical Comics 128 Two Case Studies 6 Whither the Graphic Novel? 152 Notes 164 Works Cited 169 Index 177 This page intentionally left blank ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Who can do this sort of thing alone? Not I. Thanks are due to many. For permission to include passages from my article, “Heartbreak Soup: The Interdependence of Theme and Form” (Inks 4:2, May 1997), the Ohio State University Press. -

Comics for Teaching Content

Comics for Teaching Content Why Teach With Comics And Graphic Novels? Comics and graphic novels, also known as sequential art or graphic texts, combine images and text in sequence to convey meaning. Recently the format has begun to gain acceptance in the teaching of literacy for all types of readers: beginning or struggling readers, English Language Learners, and advanced readers. In addition to the power of comics to teach and extend literacy skills, the comic format is also a powerful tool for teaching content! The Three E's of Comics: • Engagement: Comics require readers to actively engage in making meaning from text and images. • Efficiency: The comic format conveys a great deal of information in a short time. • Effectiveness: Processing text and images together leads to better recall and transfer of learning. The comic format requires students to actively engage in decoding both the text and the images and the interplay between them. And while readers can gain a great deal of information quickly through the visual nature of comics, they are also able to control the pace of their learning. Jonathan Hennessey, author of The United States Constitution: A Graphic Adaptation, and The Gettysburg Address: A Graphic Adaptation, explains: "I think the interplay of words and pictures has a way of engaging many aspects of the human mind at once, and can create a powerful experience of interacting with emotions and ideas. Unlike movies, however, the reader can go at his own pace. He can be more involved and active in the experience. In one image or composition, the reader can linger over the potential significance of small details without having the sense that the narrative flow has been disrupted. -

Joe Sacco's Palestine and the Uses of Graphic Narrative for (Post)

ariel: a review of international english literature Vol. 45 No. 1-2 Pages 103–129 Copyright © 2014 The Johns Hopkins University Press and the University of Calgary Sounding the Occupation: Joe Sacco’s Palestine and the Uses of Graphic Narrative for (Post)Colonial Critique Rose Brister Abstract: Working at the intersection of postcolonial literary studies and comics narratology, this paper argues that Joe Sacco’s graphic narrative Palestine contributes a spatial and sonic record of territorial occupation to the Palestinian national narrative. Sacco utilizes the comics form to represent the complex of physi- cal borders and spatial narratives he encounters in the Occupied Palestinian Territories at the end of the first Intifada. Further, he renders graphically the epiphenomenal sonic regime resulting from spatial management. Rather than an absence or gap in the Palestinian narrative, Sacco understands spatialized sound as a presence or marker of materiality. Ultimately, Palestine suggests the rich potential of the comics form for postcolonial literary stud- ies. Sacco’s graphic narrative reinvigorates the field’s engagement with literary representations of Israel-Palestine by demonstrating the continued utility of the (post)colonial paradigm and by chal- lenging the fields’ scholars to forge new interdisciplinary links to comics studies. Keywords: Palestine, Israel, graphic narrative, textual space and sound, postcolonial In “Permission to Narrate” (1984), Edward Said assesses the state of the Palestinian national narrative shortly after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. He laments that it draws from “a small archive . discussed in terms of absences and gaps—in terms of either pre-narrative or, in a sense, anti-narrative. -

Comic Creator Half the Length and Covers Three People

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS him about the beauty of a flower being accessible to both the artist and the scientist in different ways, and how they add to each other. So the comic format is valid. Why did you decide not to present his life chronologically? We asked: what would Feynman do? In his books, Feynman wrote in short scenes and acts, presenting some things out of order. A continuous narrative — born, lived, died — did not serve the person or the story. So BOOKS SECOND AND L. MYRICK/FIRST J. OTTAVIANI using anecdotes seemed natural. Choos- ing the anecdotes, choosing when to break the continuity, that was when it got more difficult. Our intention was to make him seem more human. The words and pictures in your book tell different aspects of the story. Why did you choose such a challenging format? Leland and I assumed that the readership would be willing to read both the words and the pictures. We wanted to bring something new, to enrich the experience. Otherwise, why do another book about Feynman? We wanted to go beyond James Gleick’s 1992 book Genius or Feynman’s own stories. Jim Ottaviani’s comic-strip biography of Richard Feynman conveys the physicist’s colourful personality. What is the subject of your next book? It is aimed at a young readership, and is about primatologists Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas, with a good Q&A Jim Ottaviani helping of their mentor Louis Leakey. The book is targeted at readers aged between 10 and 12, mainly girls. It is nowhere near as in-depth as Feynman, because it is about Comic creator half the length and covers three people. -

Joe Sacco: Panels, Journalism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

TRANSLATED ARTICLES 122 Mónica Yoldi · Eme nº 5 · 2017 ISSN 2253-6337 JOE SACCO: PANELS, JOURNALISM AND THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT Mónica Yoldi BA and PhD in Fine Arts by the Universitat de Barcelona (University of Barcelona) The article focuses on the work on Palestine The Novel of Nonel and Vovel by Oreet Ashery by journalist and cartoonist Joe Sacco. Mem- and Larissa Sansour that tells the story of two art- ber of the current denominated journalistic ists that have superpowers (alter egos of the two comic, Joe Sacco, through his direct, commit- authors of the comic) and fifty female ninjas who ted drawings, offers his particular view of the have the mission of saving Palestine. But in this Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He tries to avoid realm, the work of the comic artist and journalist preconceptions and common places. In this Joe Sacco (Malta, 1960) leads the trend of comic- text we analyse his main comic books, such as journalism that approaches reality to narrate, as a Palestine or Footnotes in Gaza. journalistic report, armed conflicts such as the one that is taking place between Palestine and Israel. Key words: Joe Sacco spent two months in Palestine be- Joe Sacco, journalistic comic, cartoons, Israeli- tween 1991 and 1992 “My interests in the Near Palestinian conflict, Palestine. East,” he remarks, “did not begin as a consequence of the war itself, but rather as a matter of social For some time now, contemporary comic has ap- justice. I grew up thinking the Palestinians were proached current events and narrates stories of terrorists and for many reasons. -

La Bande Dessinée En Dissidence Comics in Dissent

Collection ACME La bande dessinée en dissidence Alternative, indépendance, auto-édition Comics in Dissent Alternative, Independence, Self-Publishing Christophe Dony, Tanguy Habrand et Gert Meesters (éditeurs) Presses Universitaires de Liège 2014 Reassessing the Mainstream vs. Alternative/Independent Dichotomy or, the Double Awareness of the Vertigo Imprint Christophe Dony Université de Liège Abstract This article examines how the traditional mainstream vs. alternative/independent dicho- tomy usually employed to characterize the cultural production of comics in the US may have become outdated, and perhaps even obsolete, when considering and analyzing the editorial policies and ideological agenda of Vertigo, DC’s adult-oriented imprint. More specifically, this essay sheds light on how Vertigo engages in a critical, ironic, and sometimes ambiguous discourse with both the history of the medium and staple practices and traditions from the mainstream and alternative wings of the American comics production. In so doing, I maintain that Vertigo is characterized by a hybrid identity and has developed a “double awareness” that allows it to appeal to both mainstream and alternative audiences. Vertigo’s hybridity, however, is not devoid of cultural, political, and even sociological implications that upset the categories of reception and production structuring the field of American comics. These im plications underlying both the hybrid character of the label and its concomitant politics of demarcation in regards to the mainstream/alternatve dialectic will first be explored through the label’s obsession with processes of rewriting and recuperation, and second, through a close-reading of some of Vertigo promotional books’ covers. Résumé À la lumière d’une étude de cas examinant les pratiques éditoriales ainsi que le discours politique et culturel du label américain de bande dessinée Vertigo (DC Comics), cet article illustre la faillibilité du modèle binaire mainstream vs. -

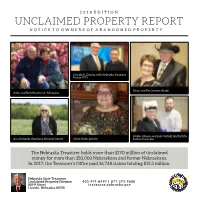

Unclaimed Property Report Notice to Owners of Abandoned Property

2018 EDITION UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORT NOTICE TO OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY Tom Rock, Omaha, with Nebraska Treasurer Photo by KETV Karen and Ken Sawyer, Brady Ardys and Herb Roszhart Jr., Marquette Walter Johnson and Josh Gartrell, North Platte Ann Zacharias Grosshans, Nemaha County Alicia Deats, Lincoln Photo by Tammy Bain The Nebraska Treasurer holds more than $170 million of unclaimed money for more than 350,000 Nebraskans and former Nebraskans. In 2017, the Treasurer’s Office paid 16,748 claims totaling $15.3 million. Nebraska State Treasurer Unclaimed Property Division 402-471-8497 | 877-572-9688 809 P Street treasurer.nebraska.gov Lincoln, Nebraska 68508 Tips from the Nebraska State Treasurer’s Office Filing a Claim If you find your name on these pages, follow any of these easy steps: • Complete the claim form and mail it, with documentation, to the Unclaimed Property Division, 809 P Street, Lincoln, NE 68508. • For amounts under $500, you may file a claim online at treasurer.nebraska.gov. Include documentation. • Call the Unclaimed Property Division at 402-471-8497 or 1-877-572-9688 (toll free). • Stop by the Treasurer’s Office in Suite 2005 of the Capitol or the Unclaimed Property Division at 809 P Street in Lincoln’s Haymarket. Hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Recognizing Unclaimed Property Unclaimed property comes in many shapes and sizes. It could be an uncashed paycheck, an inactive bank account, or a refund. Or it could be dividends, stocks, or the contents of a safe deposit box. Other types are court deposits, utility deposits, insurance payments, lost IRAs, matured CDs, and savings bonds. -

Frank Stack Collection

Special Collections 401 Ellis Library Columbia, MO 65201 & Rare Books (573) 882-0076 [email protected] University of Missouri Libraries http://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/ Frank Stack Collection Stack, Frank. b. 1937. Papers, 1957- MU Ellis Special Collections Comic Collection 2 1/2 linear feet Scope and Contents Note The collection contains material published from Stack’s college days, through the early underground comic book period, and to the publication of our Cancer Year in 1995. An extensive collection of letters from Gilbert Shelton, William Helmer, the Rip Off Press and others is included. Continuities by Harvey Pekar for which Stack prepared art work are in the collection. Provenance The material in the collection was originally donated by Frank Stack, with several subsequent additions. Photocopies of articles about the artist and his work have been made for inclusion in the collection. Restrictions on Access Most of the collection is available to all researchers, however, permission to use Folders 32-34 must be obtained from Frank Stack. Permission to publish material in the collection must be obtained from the Head of Special Collections. Selected items may also require permission from Frank Stack. Inquire with Special Collections for details. Biographical Sketch Frank Stack was born October 31, 1937 in Houston, Texas. He was educated at the University of Texas (B.F.A.), University of Wyoming (M.A.) and received additional training at the School of Art Institute of Chicago and Academie Grande Chaumiere of Paris. Stack was editor of Texas Ranger magazine 1957-1959 while at the University of Texas. Stack names his biggest creative influences as Gustave Dore, Roy Crane and V.T. -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Updated March 18, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL34074 SUMMARY RL34074 The Palestinians: Background and U.S. March 18, 2021 Relations Jim Zanotti The Palestinians are an Arab people whose origins are in present-day Israel, the West Bank, and Specialist in Middle the Gaza Strip. Congress pays close attention—through legislation and oversight—to the ongoing Eastern Affairs conflict between the Palestinians and Israel. The current structure of Palestinian governing entities dates to 1994. In that year, Israel agreed with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to permit a Palestinian Authority (PA) to exercise limited rule over Gaza and specified areas of the West Bank, subject to overarching Israeli military administration that dates back to the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. After the PA’s establishment, U.S. policy toward the Palestinians focused on encouraging a peaceful resolution to the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, countering Palestinian terrorist groups, and aiding Palestinian goals on governance and economic development. Since then, Congress has appropriated more than $5 billion in bilateral aid to the Palestinians, who rely heavily on external donor assistance. Conducting relations with the Palestinians has presented challenges for several Administrations and Congresses. The United States has historically sought to bolster PLO Chairman and PA President Mahmoud Abbas vis-à-vis Hamas (a U.S.- designated terrorist organization supported in part by Iran). Since 2007, Hamas has had de facto control within Gaza, making the security, political, and humanitarian situation there particularly fraught. The Abbas-led PA still exercises limited self-rule over specified areas of the West Bank. -

Refugees Or Returnees: European Jews, Palestinian Arabs And

STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA CX Ulf Carmesund Refugees or Returnees European Jews, Palestinian Arabs and the Swedish Theological Institute in Jerusalem around 1948 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Geijersalen, Thun- bergsvägen 3P, Uppsala, Friday, October 1, 2010 at 14:00 for the degree of Doctor of Theolo- gy. The examination will be conducted in Swedish. Abstract Carmesund, U. 2010. Refugees or Returnees. European Jews, Palestinian Arabs and the Swe- dish Theological Institute in Jerusalem around 1948. Uppsala Universitet. Studia Missionalia Svecana CX. 265 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-506-2145-7. In this study five individuals who worked in Svenska Israelsmissionen and at the Swedish Theological Institute in Jerusalem are focused. These are Greta Andrén, deaconess in Svenska Israelsmissionen from 1934 and matron at the Swedish Theological Institute from 1946 to 1971, Birger Pernow, director of Svenska Israelsmissionen from 1930 to 1961, Harald Sahlin director of the Swedish Theological Institute in 1947, Hans Kosmala director of the Swedish Theological Institute from 1951 to 1971, and finally H.S. Nyberg, Chair of the Swedish board of the Swedish Theological Institute from 1955 to 1974. The study uses theoretical perspec- tives from Hannah Arendt, Mahmood Mamdani and Rudolf Bultmann. A common idea among Lutheran Christians in the first half of 20th century Sweden implied that Jews who left Europe for Palestine or Israel were not just seen as refugees or colonialists - but viewed as returnees, to the Promised Land. The idea of peoples’ origins, and original home, is traced in European race thinking. This study is discussing how many of the studied individuals combined superstitious interpretations of history with apocalyptic interpretations of the Bible and a Romantic national ideal.