Joe Sacco's Palestine and the Uses of Graphic Narrative for (Post)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Am Lit 1945-Present List

Renee Hudson American Literature 1945-Present (Ngai) Primary Texts: 1. A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams (1947) 2. Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith (1950) 3. The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1953) 4. A Good Man is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor (1955) 5. Howl by Allen Ginsberg (1956) 6. Catch-22 by Joseph Heller (1961) 7. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee (1962) 8. The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (1962) 9. Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara (1964) 10. Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965) 11. Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed (1972) 12. Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon (1973) 13. Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow (1975) 14. Meridian by Alice Walker (1976) 15. Buried Child by Sam Shepard (1978) 16. Sixty Stories by Donald Barthelme (1982) 17. Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1982) 18. Great Expectations by Kathy Acker (1983) 19. Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy (1985) 20. White Noise by Don DeLillo (1985) 21. Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987) 22. The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker (1990) 23. Woman Hollering Creek by Sandra Cisneros (1991) 24. Patchwork Girl by Shelley Jackson (1995) 25. Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace (1996) 26. Tropic of Orange by Karen Tei Yamashita (1997) 27. American Pastoral by Philip Roth (1997) 28. Palestine by Joe Sacco (2001) 29. Pattern Recognition by William Gibson (2003) 30. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz (2007) Renee Hudson Secondary Texts: 1. The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord (1973) 2. -

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE (Div

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE (Div. I) Chair, Associate Professor CHRISTOPHER NUGENT Professors: BELL-VILLADA, CASSIDAY, DRUXES, S. FOX, FRENCH, KAGAYA**, NEWMAN***, ROUHI, VAN DE STADT. Associate Professors: C. BOLTON***, DEKEL, S. FOX, HOLZAPFEL, MARTIN, NUGENT, PIEPRZAK***, THORNE, WANG**. Assistant Professors: BRAGGS*, VARGAS. Visiting Assistant Professor: EQEIQ. Students motivated by a desire to study literary art in the broadest sense of the term will find an intellectual home in the Program in Comparative Literature. The Program in Comparative Literature gives students the opportunity to develop their critical faculties through the analysis of literature across cultures, and through the exploration of literary and critical theory. By crossing national, linguistic, historical, and disciplinary boundaries, students of Comparative Literature learn to read texts for the ways they make meaning, the assumptions that underlie that meaning, and the aesthetic elements evinced in the making. Students of Comparative Literature are encouraged to examine the widest possible range of literary communication, including the metamorphosis of media, genres, forms, and themes. Whereas specific literature programs allow the student to trace the development of one literature in a particular culture over a period of time, Comparative Literature juxtaposes the writings of different cultures and epochs in a variety of ways. Because interpretive methods from other disciplines play a crucial role in investigating literature’s larger context, the Program offers courses intended for students in all divisions of the college and of all interests. These include courses that introduce students to the comparative study of world literature and courses designed to enhance any foreign language major in the Williams curriculum. In addition, the Program offers courses in literary theory that illuminate the study of texts of all sorts. -

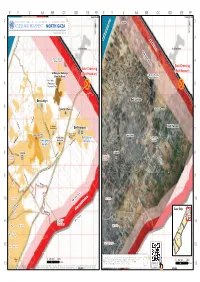

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

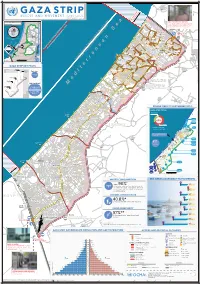

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Considering Ethical Questions in (Non)Fiction: Reading and Writing About Graphic Novels

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Considering Ethical Questions in (Non)Fiction: Reading and Writing about Graphic Novels Gene McQuillan Kingsborough Community College /The City University of New York Brooklyn, NY, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT Teachers often feature graphic novels in college courses, and recent research notes how these texts can help make the process of reading more engaging as well as more complex. Graphic novels help enhance a variety of “literacies”; they offer bold representations of people dealing with trauma or marginalization; they explore how “texts” can be re-invented; they exemplify how verbal and visual texts are often adapted; they are ideal primers for introducing basic concepts of “post-modernism.” However, two recurring textual complications in graphic novels can pose difficulties for students who are writing about ethical questions. First, graphic novels often present crucial scenes by relying heavily on the use of verbal silence (or near silence) while emphasizing visual images; second, the deeper ethical dimensions of such scenes are suggested rather than discussed through narration or dialogue. This article will explain some of the challenges and options for writing about graphic novels and ethics. Keywords: Graphic novels; ethics; literacies; Art Spiegelman; Maus; Alison Bechdel; Fun Home 38 Volume 5, Issue 1 Considering Ethical Questions in (Non)Fiction I am committed to using graphic novels in my English courses. This commitment can be a heavy one- -in my case, it sometimes weighs about 40 pounds. If one stopped by my Introduction to Literature course at Kingsborough Community College (the City University of New York), one could see exactly what I mean. -

Comics As a Medium Dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds David Eric Low University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Low, David Eric, "Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1090. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1090 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1090 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comics as a Medium dor Inquiry: Urban Students (Re-)Designing Critical Social Worlds Abstract Literacy scholars have argued that curricular remediation marginalizes the dynamic meaning-making practices of urban youth and ignores contemporary definitions of literacy as multimodal, socially situated, and tied to people's identities as members of cultural communities. For this reason, it is imperative that school-based literacy research unsettle status quos by foregrounding the sophisticated practices that urban students enact as a result, and in spite of, the marginalization they manage in educational settings. A hopeful site for honoring the knowledge of urban students is the nexus of alternative learning spaces that have taken on increased significance in ouths'y lives. Many of these spaces focus on young people's engagements with new literacies, multimodalities, the arts, and popular media, taking the stance that students' interests are inherently intellectual. The Cabrini Comics Inquiry Community (CCIC), located in a K-8 Catholic school in South Philadelphia, is one such space. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights

11/17/2016 Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continued to use excessive force in the oPt 6 Palestinian civilians, including 2 children, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. House demolitions on grounds of collective punishment. A room was closed with concrete in Yatta, south of Hebron. Israeli forces conducted 64 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and 6 ones in occupied Jerusalem. 57 civilians, including 15 children and a woman, were arrested. Fifteen of them, including 12 children and the woman, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. The Health Improvement Program’s office in Ramallah was raided and some of its content were confiscated. Israeli forces continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip Sea. 2 fishermen were arrested and their fishing boat was confiscated, north of the Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued their efforts to create Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem. 2 residential apartments in alMukaber Mount and 2 stores in Beit Hanina were selfdemolished by their owners. 2 barracks, an agricultural room and a mosque foundation in Silwan and Sour Baher villages were demolished. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 2 agricultural rooms in Qalqilya and a residential tent, a social service centre and a well, south of Hebron, were demolished. -

A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28 Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 20

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 The Westin Copley Place 10 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02116 Conference Director: Olivia Carr Edenfield Georgia Southern University American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 Acknowledgements: The Conference Director, along with the Executive Board of the ALA, wishes to thank all of the society representatives and panelists for their contributions to the conference. Special appreciation to those good sports who good-heartedly agreed to chair sessions. The American Literature Association expresses its gratitude to Georgia Southern University and its Department of Literature and Philosophy for its consistent support. We are grateful to Rebecca Malott, Administrative Assistant for the Department of Literature and Philosophy at Georgia Southern University, for her patient assistance throughout the year. Particular thanks go once again to Georgia Southern University alumna Megan Flanery for her assistance with the program. We are indebted to Molly J. Donehoo, ALA Executive Assistant, for her wise council and careful oversight of countless details. The Association remains grateful for our webmaster, Rene H. Treviño, California State University, Long Beach, and thank him for his timely service. I speak for all attendees when I express my sincerest appreciation to Alfred Bendixen, Princeton University, Founder and Executive Director of the American Literature Association, for his 28 years of devoted service. We offer thanks as well to ALA Executive Coordinators James Nagel, University of Georgia, and Gloria Cronin, Brigham Young University. -

Burma Chronicles and Guibert, Lefèvre, and Lemercier’S the Photographer

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies 5 (2014) 23-44. Graphic Self-Consciousness, Travel Narratives, and the Asian American Studies Classroom: Delisle’s Burma Chronicles and Guibert, Lefèvre, and Lemercier’s The Photographer By Monica Chiu As graphic narratives find solid purchase in the literary marketplace and in academia, students flock to related courses. I recently experienced this enthusiasm when I offered an upper-level Asian American graphic narratives course that filled beyond capacity, the first time this umbrella course for the field of Asian American studies had ever over enrolled in the fifteen years I had taught at my New England- based institution. In the course, students first grappled with comics terminology, introduced through Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Thierry Groensteen’s The System of Comics. After this basic introduction to reading verbal-visual texts, we discussed those by and about Asian Americans: Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’s Skim, Tofic El Rassi’s Arab in America, among others. These comics rely on recognizable (stereotypical) images of Asians and Asian Americans to expose accepted types and then to subvert or dismantle them. Students were most challenged by the autobiographical Burma Chronicles (2008) by Guy Delisle and The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders (2009), an artistic collaboration among Didier Lefèvre’s photographs, which served as an impetus for the text; Emmanuel Guibert’s comic art; and colorist Frédéric Lermercier’s book design. Delisle’s and Lefèvre’s travel narratives by non-Asian Americans about Southeast Asians (Burmese) and West Asians (Afghans) asked students to consider the self-representation of the comics’ Canadian and French protagonists, respectively, as they navigated foreign territories. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp.