A Spirited Life by Bob Andelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

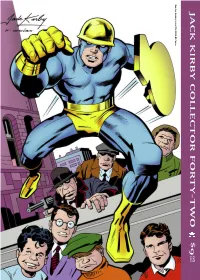

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Vol. 72, Ed. 10 | the West Georgian Editorial Generation Generalization Jaenaeva Watson on the Role of Breaking the Odds and Start a Pasta Business?” Their Talents

The West GeorgianEst. 1934 Volume 72, Edition Ten November 13 - November 19, 2017 In this DINING WITH MARVEL VS DC HOOP UP Who rules the box UWG ready for edition... WOLVES UWG students office? basketball season learn table / / PAGE 4 / / PAGE 7 etiquitte / / PAGE 2 A Star is Leaving UWG Photo Courtesy of Dr. Bob Powell Photo Courtesy of Dr. Photo Credit: Steven Broome Jamie Walloch his students’ names. interacting with the physics majors as In 2005, Powell became chair of the well as others that I taught in science Contributing Writer Physics and Astronomy department instead courses, compared to today’s students who of retiring. presumably are better prepared. I am not Even a health problem in 2014 did so sure that our current students work quite Dr. Bob Powell is retiring from UWG after not stop the dedicated professor from doing as hard and really remember and can apply 50 years of dedication to serving students what he loves. He continued teaching after things that they should have learned in within his teachings of physics and recovery and decided to retire after exactly earlier courses, however.” astronomy along with serving as director of 50 years and one semester of teaching. In Fall 1971, Powell became a the Observatory and a faculty advisor. “The obvious time for me to retire faculty advisor for the Chi Omega Sorority. A In September of 1967, Powell began was May of last year but I like the fall member of the sorority and a student in his teaching at West Georgia College at 26 semester,” said Powell. -

{PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50'S Horror and SF Comics by Alex Toth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50's Horror and S.F. Comics by Alex Toth Dick Briefer's Frankenstein: The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics HC (2010 IDW) comic books. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 1st printing. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. Frankenstein! Dick Briefer is one of the seminal artists who worked with Will Eisner on some of the very first comic books. If you like the comic-book weirdness of cartoonists Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, and Boody Rogers, you're sure to thrill over Dick Briefer's creation of Frankenstein. The large-format book lovingly reproduces a monstrous number of stories from the original 1940s and '50s comic books. The stories are fascinatingly supplemented by an insightful introduction with rare photos of the artist, original art, letters from Dick Briefer, drawings by Alex Toth inspired by Briefer's Frankenstein-and much more! Hardcover, 112 pages, full color. Cover price $21.99. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 2nd or later printings. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. -

Studies in Literature and Culture: the Graphic Novel

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators Studies in Literature and Culture: The Graphic Novel • REQUIRED TEXTS: Chynna Clugston-Major, Blue Monday: Absolute Beginners (Oni Press) Will Eisner, A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories (DC Comics) Mike Gold (Ed.), The Greatest 1950s Stories Ever Told (DC Comics) Harold Gray, Little Orphan Annie: The Sentence (Pacific Comics Club) Jason Lutes, Jar of Fools (Drawn & Quarterly) Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics (Harper-Perennial) Frank Miller and David Mazzuchelli, Batman: Year One (DC Comics) Art Spiegelman, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (Vol. I) (Pantheon) James Sturm, The Revival (Bear Bones Press) You will also need the following: • A notebook. I would like you to keep track of major points which come up in my lectures and also in our class discussions. • A folder or binder for reserve readings and class handouts. I would suggest you make copies of the reserve readings available at the library. I will also give you a number of photocopied handouts which include directed-reading questions and material which supplements the primary readings for the course. • GRADES ––Attendance and class participation (including short response papers and reading quizzes): 25% ––Writing Assignment/Mini-comic project: 25% ––Midterm exam: 25% ––Final exam: 25% * Your papers must be turned in on time! I will deduct a full grade for each day a paper is late. If you have any questions about your papers or the assigned paper topics, please see me during my office hours or by appointment. I will be glad to talk with you about our readings and about your essays. -

A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duncan, Ralph Randolph II, "Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4910. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4910 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualityof this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copysubmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

September 2007 Caa News

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLLEGE ART ASSOCIATION VOLUME 32 NUMBER 5 SEPTEMBER 2007 CAA NEWS Cultural Heritage in Iraq SEPTEMBER 2007 CAA NEWS 2 CONTENTS FEATURES 3 Donny George Is Dallas–Fort Worth Convocation Speaker FEATURES 4 Cultural Heritage in Iraq: A Conversation with Donny George 7 Exhibitions in Dallas and Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum 8 Assessment in Art History 13 Art-History Survey and Art- Appreciation Courses 13 Lucy Oakley Appointed caa.reviews Editor-in-Chief 17 The Bookshelf NEW IN THE NEWS 18 Closing of CAA Department Christopher Howard 19 National Career-Development Workshops for Artists FROM THE CAA NEWS EDITOR 19 MFA and PhD Fellowships Christopher Howard is editor of CAA News. 21 Mentors Needed for Career Fair 22 Participating in Mentoring Sessions With this issue, CAA begins the not-so-long road to the next 22 Projectionists and Room Monitors Needed Annual Conference, held February 20–23, 2008, in Dallas and 24 Exhibit Your Work at the Dallas–Fort Fort Worth, Texas. The annual Conference Registration and Worth Conference Information booklet, to be mailed to you later this month, 24 Annual Conference Update contains full registration details, information on special tours, workshops, and events at area museums, Career Fair instruc- CURRENTS tions, and much more. This publication, as well as additional 26 Publications updates, will be posted to http://conference.collegeart.org/ 27 Advocacy Update 2008 in early October. Be sure to bookmark that webpage! 27 Capwiz E-Advocacy This and forthcoming issues of CAA News will also con- tain crucial conference information. On the next page, we 28 CAA News announce Donny George as our Convocation speaker. -

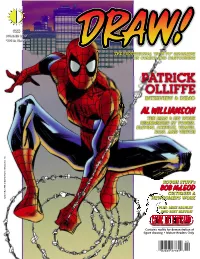

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Jenette Kahn

Characters TM & © DC Comics. All rights reserved. 0 6 No.57 July 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! JENETTE KAHN president president and publisher with former DC Comics An in-depth interview imprint VERTIGO DC’s The birth of ALSO: Volume 1, Number 57 July 2012 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks EISNER AWARDS COVER DESIGNER 2012 NOMINEE Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS BEST COMICS-RELATEDJOURNALISM Karen Berger Andy Mangels Alex Boney Nightscream BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 John Costanza Jerry Ordway INTERVIEW: The Path of Kahn . .3 DC Comics Max Romero Jim Engel Bob Rozakis A step-by-step survey of the storied career of Jenette Kahn, former DC Comics president and pub- Mike Gold Beau Smith lisher, with interviewer Bob Greenberger Grand Comic-Book Roy Thomas Database FLASHBACK: Dollar Comics . .39 Bob Wayne Robert Greenberger This four-quarter, four-color funfest produced many unforgettable late-’70s DCs Brett Weiss Jack C. Harris John Wells PRINCE STREET NEWS: Implosion Happy Hour . .42 Karl Heitmueller Marv Wolfman Ever wonder how the canceled characters reacted to the DC Implosion? Karl Heitmueller bellies Andy Helfer Eddy Zeno Heritage Comics up to the bar with them to find out Auctions AND VERY SPECIAL GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The Lost DC Kids Line . .45 Alec Holland THANKS TO Sugar & Spike, Thunder and Bludd, and the Oddballs were part of DC’s axed juvie imprint Nicole Hollander Jenette Kahn Paul Levitz BACKSTAGE PASS: A Heroine History of the Wonder Woman Foundation .