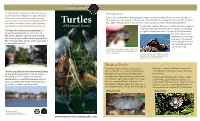

A Look at Alabama's SNAPPING Turtles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

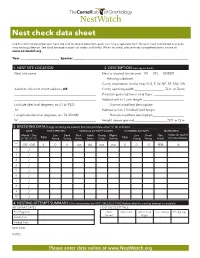

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina Rylen Nakama FISH 423: Olden 12/5/14 Figure 1. The Common Snapping Turtle, one of the most widespread reptiles in North America. Photo taken in Quebec, Canada. Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/yorthopia/7626614760/. Classification Order: Testudines Family: Chelydridae Genus: Chelydra Species: serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) Previous research on Chelydra serpentina (Phillips et al., 1996) acknowledged four subspecies, C. s. serpentina (Northern U.S. and Figure 2. Side profile of Chelydra serpentina. Note Canada), C. s. osceola (Southeastern U.S.), C. s. the serrated posterior end of the carapace and the rossignonii (Central America), and C. s. tail’s raised central ridge. Photo from http://pelotes.jea.com/AnimalFact/Reptile/snapturt.ht acutirostris (South America). Recent IUCN m. reclassification of chelonians based on genetic analyses (Rhodin et al., 2010) elevated C. s. rossignonii and C. s. acutirostris to species level and established C. s. osceola as a synonym for C. s. serpentina, thus eliminating subspecies within C. serpentina. Antiquated distinctions between the two formerly recognized North American subspecies were based on negligible morphometric variations between the two populations. Interbreeding in the overlapping range of the two populations was well documented, further discrediting the validity of the subspecies distinction (Feuer, 1971; Aresco and Gunzburger, 2007). Therefore, any emphasis of subspecies differentiation in the ensuing literature should be disregarded. Figure 3. Front-view of a captured Chelydra Continued usage of invalid subspecies names is serpentina. Different skin textures and the distinctive pink mouth are visible from this angle. Photo from still prevalent in the exotic pet trade for C. -

Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina, Overland Movements Near the Southeastern Extent of Its Range David A

Georgia Journal of Science Volume 68 No. 2 Scholarly Contributions from the Article 11 Membership and Others 2010 Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina, Overland Movements Near the Southeastern Extent of its Range David A. Steen [email protected] Sean C. Sterrett Aubrey M. Heupel Lora L. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Steen, David A.; Sterrett, Sean C.; Heupel, Aubrey M.; and Smith, Lora L. (2010) "Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina, Overland Movements Near the Southeastern Extent of its Range," Georgia Journal of Science, Vol. 68, No. 2, Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs/vol68/iss2/11 This Research Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ the Georgia Academy of Science. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia Journal of Science by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ the Georgia Academy of Science. 196 Steen et al.: Snapping Turtle Overland Movements SNAPPING Turtle, CHELYDRA SERPENTINA, OVERLAND MOVEMENTS NEAR THE SOUTHEASTERN EXTENT OF ITS RANGE David A. Steen1,2*, Sean C. Sterrett2, Aubrey M. Heupel2 and Lora L. Smith2 1Auburn University, 331 Funchess Hall, Auburn, Alabama, 36849 2Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center Route 2, Box 2324, Newton, GA 39870 Institution at which work was completed: Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Terrestrial movements of turtles are of interest due to the conserva- tion implications for this imperiled group and the general lack of information on this topic, particularly in wide-ranging species. -

Turtles of the Upper Mississippi River System

TURTLES OF THE UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER SYSTEM Tom R. Johnson and Jeffrey T. Briggler Herpetologists Missouri Department of Conservation Jefferson City, MO March 27, 2012 Background: A total of 13 species and subspecies of turtles are known to live in the Upper Mississippi River, its backwaters and tributaries. There are a few species that could be found occasionally, but would likely account for less than 5% of the species composition of any area. These species are predominantly marsh animals and are discussed in a separate section of this paper. For additional information on turtle identification and natural history see Briggler and Johnson (2006), Christiansen and Bailey (1988), Conant and Collins (1998), Ernst and Lovich (2009), Johnson (2000), and Vogt (1981). This information is provided to the fisheries field staff of the LTRM project so they will be able to identify the turtles captured during fish monitoring. The most current taxonomic information of turtles was used to compile this material. The taxonomy followed in this publication is the Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with comments regarding confidence in our understanding (6th edition) by Crothers (2008). Species Identification, Natural History and Distribution: What follows is a synopsis of the 13 turtle species and subspecies which are known to occur in the Upper Mississippi River environs. Species composition changes between the upper and lower reaches of the LTRM study area (Wisconsin/Minnesota state line and southeastern Missouri) due to changes in aquatic habitats. For example, the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica) is abundant in the northern portion of the river with clearer water and abundant snail prey. -

Bird Nests What Is a Bird's Nest?

Duke Gardens Winter Fun at Home BIRD NESTS Winter can be a good time to spot bird nests in bare tree branches that lost their leaves in the fall. Have you ever spotted any bird nests or squirrel dreys in a tree? (Drey is the word for a squirrel nest, and they usually look like a messy ball of sticks and leaves). WHAT IS A BIRD’S NEST? All birds start their life cycle as an egg. Eggs need to be protected from weather and predators. An egg also needs to stay warm from the time it is laid until it hatches. This is called the incubation period. A nest is the shelter most adult birds build to protect their eggs until A squirrel drey they hatch and to keep baby birds safe until they are ready to leave (not a bird nest!) the nest. Nests range in size, shape, location and building materials, and all of these can be clues about the kind of bird that made it. For example, bald eagle nests can be 5-6 feet across, while a cardinal’s nest is about 4 inches across. Hummingbird nests can be as small as a thimble when they are built, but they are made with materials that allow the nest to stretch as the baby birds inside it grow. Nests can be built in many places. Some birds make cavity nests inside something by finding or making an opening inside a tree, a stump or a nest box. Carolina wrens, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and some owls are a few examples of cavity nesting birds. -

A Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles

A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks This publication may be cited as: Bandas, Sarah J., and Kenneth F. Higgins. 2004. Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles. SDCES EC 919. Brookings: South Dakota State University. Copies may be obtained from: Dept. of Wildlife & Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University Box 2140B, NPBL Brookings SD 57007-1696 South Dakota Dept of Game, Fish & Parks 523 E. Capitol, Foss Bldg Pierre SD 57501 SDSU Bulletin Room ACC Box 2231 Brookings, SD 57007 (605) 688–4187 A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks Sarah J. Bandas Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Kenneth F. Higgins U.S. Geological Survey South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Contents 2 Introduction . .3 Status of South Dakota turtles . .3 Fossil record and evolution . .4 General turtle information . .4 Taxonomy of South Dakota turtles . .9 Capturing techniques . .10 Turtle handling . .10 Turtle habitats . .13 Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) . .15 Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) . .17 Spiny Softshell Turtle (Apalone spinifera) . .19 Smooth Softshell Turtle (Apalone mutica) . .23 False Map Turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) . .25 Western Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata) . -

North Louisiana Refuges Complex: Freshwater Turtle Inventory

NORTH LOUISIANA REFUGES COMPLEX: FRESHWATER TURTLE INVENTORY USFWS Award No: F17PX01556 John L. Carr, Aaron C. Johnson & J. Benjamin Grizzle November 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Inventory and Monitoring Branch for USFWS Award No. F17PX01556, “Freshwater Turtle Inventory of the North Louisiana Refuges Complex”. In addition, this report incorporates data from other, complementary projects that were funded by a variety of sources. This has been done in order to provide a more fulsome picture of knowledge on the turtle fauna of the refuges within the Complex. These other projects were funded in part by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Aid, through the State Wildlife Grants Program (series of projects targeting the Alligator Snapping Turtle and map turtles). Other sources include data collected for grant activities funded by USGS-BRD (Cooperative Agreement No. 99CRAG0017), funding from the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Foundation beginning in 1998, funding directly from LDWF (2000-2002), The Nature Conservancy (contract #LAFO_022309), Friends of Black Bayou, the Turtle Research Fund of the University of Louisiana at Monroe Foundation, and the Kitty DeGree Professorship in Biology (2011-2017). U.S. Fish and Wildlife personnel helped facilitate our work by granting access to all parts of the refuges at various times, and providing a series of Special Use Permits over 20+ years. We acknowledge Lee Fulton, Joe McGowan, Brett Hortman, Kelby Ouchley, and George Chandler for facilitating our work on refuges over the years; in particular, we thank Gypsy Hanks for long-sustained support and cooperation, especially during the course of the current project. -

Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus Carolinensis

eastern gray squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern gray squirrel’s head-body length is Class: Mammalia between eight and 11 inches, with its tail about the Order: Rodentia same length as the body. Its body fur is gray, and there is a border of white fur on the bushy, gray tail. Family: Sciuridae The belly fur is white, a cream line surrounds each ILLINOIS STATUS eye, and white tips are present on the back of the ears. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern gray squirrel may be found statewide in Illinois. It lives in woods or forests that have a closed canopy, nut-bearing trees and plenty of cavity trees. As these mature forests have been destroyed in Illinois, the population of gray squirrels has declined. However, gray squirrels are common in cities. Here, they live in trees without the conditions described above. The gray squirrel eats buds, leaves, fruits, berries, fungi, pecans, acorns, hickory nuts, tree bark, walnuts and the seeds of various other trees. It stores nuts in holes in the ground. This squirrel grasps food in its front paws. It is primarily arboreal, and its large, bushy tail helps it balance while climbing and resting in trees. Urban squirrels are good at climbing brick walls and walking along wires and cables. The eastern gray squirrel does not hibernate and is active during the day year-round. It ILLINOIS RANGE may sleep for several consecutive days in winter, however. Its call is “kuk-kuk-cut-cut-cut.” This animal builds a leaf nest in the high branches of a tree but may use a tree cavity for escape from predators and poor weather and for raising its young. -

Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol

CANADA GOOSE EGG ADDLING PROTOCOL The Humane Society of the United States Wild Neighbors Program 2100 L Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 (202) 452-1100 humanesociety.org/wildlife January 2009 ©The Humane Society of the United States. The HSUS Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol January 2009 Introduction Addling means “loss of development.” It commonly refers to any process by which an egg ceases to be viable. Addling can happen in nature when incubation is interrupted for long enough that eggs cool and embryonic development stops. People addle where they want to manage bird populations. Population management should be only one component of a comprehensive, integrated, humane program to resolve conflict between people and wild Canada geese (see Humanely Resolving Conflicts with Canada Geese: a Guide for Urban and Suburban Property Owners and Communities available online at humanesociety.org/wildlife). A contraceptive drug, nicarbazin sold under the brand name OvoControl (online at ovocontrol.com), reduces hatching to manage populations humanely. Geese who consume an adequate dose during egg production lay infertile eggs. Managing populations with OvoControl requires less labor than addling as you do not have to find and treat individual nests. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has registered this drug in the United States. A U.S Fish and Wildlife Agency (USFWS) permit is required. Potential users should also check to see if their state wildlife agencies require an additional permit. Complete contact information for the supplier is at the end of this Protocol. This Protocol is for Canada geese (Branta canadensis spp.) only. Other species of birds have different nesting chronologies and incubation periods that make appropriate addling different. -

Starlings and Mynas

Beneficial Starlings The Eurasian Rose-colored and African Wattled Starlings are believed Starlings to be beneficial due to their insect con trol near agricultural crops. Both species establish breeding colonies in and Mynas areas where swarms of locusts and by Susan Congdon, grasshoppers appear. It is believed that Disney's Animal Kingdom, FL they eat enough of these insects to protect food crops. banded and released have been sub Pest Starlings? he names starling and myna sequently recovered when found for There are some species of star are often used interchange sale in Indonesian bird markets. The ling/myna that are considered to be T ably similar to pigeoN. and conversion of forest to agricultural pests. The European Starling and dove. Myna is the Hindi word for star land, and deforestation for firewood Common Myna are two examples of ling and is often used for species native and human settlements have greatly this. European Starlings were intro to southern and southeastern Asia and decreased their natural habitat. duced to North America and are the southeastern Pacific. Many of the In response to the decreasing wild extremely gregarious. As well as dam Asian birds are known as both starlings population, the American Zoo and aging important crops they compete and mynas. Aquarium Association, Jersey Wildlife with native birds for hollows in which Preservation Trust, and the Indonesian to nest. Near Extinction ofthe Bali Myna government have set up a Species Common Mynas, introduced to There are 114 species in the Survival Program (SSP). The main goals many places including Hawaii and sturnidae family. -

Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations Cliff swallows present a high degree of intraspecific brood parasitism. Individuals often lay eggs in other individuals’ nests within the same colony. It has been observed that some parasitic swallows have even tossed out their neighbors’ eggs and replaced them with their own offspring. Parasitized swallows had lower success in fledging their own chicks. This behavior has been adapted to increase the parasitic swallow’s offspring’s success by passing on the burden of taking care of chicks to another individual. Solitary Barn swallow at Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS There are eight species of swallows that regularly breed in North America: the Bank swallow, Barn swallow, Cave swallow, Cliff swallow, Northern Rough-winged swallow, Purple martin, Tree swallow, and Violet-green swallow. Natural History: After migrating north from their wintering grounds, mostly in Central America, Cliff and Barn swallows often nest on cliffs, canyons, bridges, and eaves of buildings. Swallows may construct an entirely new Cliff swallows constructing their nests at Kern National nest or they may use old nests, building off of traces Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS of mud where an old nest used to be. The breeding season for swallows lasts from March through Ecological Value of Swallows: September. They often produce two clutches per Swallows provide us with an ecological service as year, with a clutch size of 3-5 eggs. Eggs incubate insect controllers. They particularly consume between 13-17 days and fledge after 18-24 days. swarming insects such as bees, wasps, flies, However, chicks return to the nest after fledging for damselflies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, and several weeks before they leave the nest for good. -

Turtles Are Reptiles--Kin to Snakes, Lizards, Alligators, and Crocodiles

Nature Series The Monmouth County Park System has two envi- ronmental centers dedicated to nature education. Introduction Each has a trained staff of naturalists to answer Turtles are reptiles--kin to snakes, lizards, alligators, and crocodiles. However, they carry part of visitor questions and a variety of displays, exhibits, their skeleton on the outside of their bodies, which makes them unique from most other animals. and hands-on activities where visitors of all ages Turtles Plus, with a lifespan of up to 80 years for some local species, they are very special indeed! can learn about area wildlife and natural history. of Monmouth County As with other reptiles, turtles are ectothermic (also known as “cold-blooded”), which means they use their surroundings The Huber Woods Environmental Center, on to regulate body temperature. To cool off, they burrow in Brown’s Dock Road in the Locust Section of the mud or hide under Middletown, features newly renovated exhibits vegetation. To warm up, about birds, plants, wildlife and the Lenape Indians. they bask in the sun. In Miles of surrounding trails offer many opportunities winter, all reptiles in our to enjoy and view nature. area must hibernate to survive the cold. Turtle Tales is a popular program offered by Park System Naturalists-here a baby painted turtle is displayed. Spend some time in the parks, especially near the water, and you will have to try hard NOT to see Painted Turtles. Threats to Turtles Road mortality is a threat to many local Bog Turtle, continued habitat destruction The Manasquan Reservoir Environmental Center, species.