Hillforts and the Durotriges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

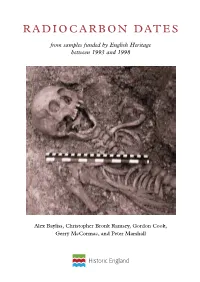

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Ancient Dumnonia

ancient Dumnonia. BT THE REV. W. GRESWELL. he question of the geographical limits of Ancient T Dumnonia lies at the bottom of many problems of Somerset archaeology, not the least being the question of the western boundaries of the County itself. Dcmnonia, Dumnonia and Dz^mnonia are variations of the original name, about which we learn much from Professor Rhys.^ Camden, in his Britannia (vol. i), adopts the form Danmonia apparently to suit a derivation of his own from “ Duns,” a hill, “ moina ” or “mwyn,” a mine, w’hich is surely fanciful, and, therefore, to be rejected. This much seems certain that Dumnonia is the original form of Duffneint, the modern Devonia. This is, of course, an extremely respectable pedigree for the Western County, which seems to be unique in perpetuating in its name, and, to a certain extent, in its history, an ancient Celtic king- dom. Such old kingdoms as “ Demetia,” in South Wales, and “Venedocia” (albeit recognisable in Gwynneth), high up the Severn Valley, about which we read in our earliest records, have gone, but “Dumnonia” lives on in beautiful Devon. It also lives on in West Somerset in history, if not in name, if we mistake not. Historically speaking, we may ask where was Dumnonia ? and who were the Dumnonii ? Professor Rhys reminds us (1). Celtic Britain, by G. Rhys, pp. 290-291. — 176 Papers, §*c. that there were two peoples so called, the one in the South West of the Island and the other in the North, ^ resembling one another in one very important particular, vizo, in living in districts adjoining the seas, and, therefore, in being maritime. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Old Oswestry Hillfort and Its Landscape: Ancient Past, Uncertain Future

Old Oswestry Hillfort and its Landscape: Ancient Past, Uncertain Future edited by Tim Malim and George Nash Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-611-0 ISBN 978-1-78969-612-7 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors and Archaeopress 2020 Cover: Painting of Old Oswestry Hillfort by Allanah Piesse Back cover: Old Oswestry from the air, photograph by Alastair Reid Please note that all uncredited images and photographs within each chapter have been produced by the individual authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Contributors ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii Preface: Old Oswestry – 80 years on �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������v Tim Malim and George Nash Part 1 Setting the scene Chapter 1 The prehistoric Marches – warfare or continuity? �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 David J. Matthews Chapter 2 Everybody needs good neighbours: Old Oswestry hillfort in context ��������������������������������������������� -

Changing Identities in a Changing Land: the Romanization of the British Landscape

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Changing Identities in a Changing Land: The Romanization of the British Landscape Thomas Ryan Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Changing Identities in a Changing Land: The Romanization of the British Landscape By Thomas J. Ryan Jr. A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2015 Thomas J. Ryan Jr. All Rights Reserved. 2015 ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis _______________ ______________________________ Date Thesis Advisor Matthew K. Gold _______________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract CHANGING IDENTITIES IN A CHANGING LAND: THE ROMANIZATION OF THE BRITISH LANDSCAPE By Thomas J. Ryan Jr. Advisor: Professor Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis This thesis will examine the changes in the landscape of Britain resulting from the Roman invasion in 43 CE and their effect on the identities of the native Britons. Romanization, as the process is commonly called, and evidence of these altered identities as seen in material culture have been well studied. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring. -

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent Papers from the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017 edited by Gary Lock and Ian Ralston Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-226-6 ISBN 978-1-78969-227-3 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover images: A selection of British and Irish hillforts. Four-digit numbers refer to their online Atlas designations (Lock and Ralston 2017), where further information is available. Front, from top: White Caterthun, Angus [SC 3087]; Titterstone Clee, Shropshire [EN 0091]; Garn Fawr, Pembrokeshire [WA 1988]; Brusselstown Ring, Co Wicklow [IR 0718]; Back, from top: Dun Nosebridge, Islay, Argyll [SC 2153]; Badbury Rings, Dorset [EN 3580]; Caer Drewyn Denbighshire [WA 1179]; Caherconree, Co Kerry [IR 0664]. Bottom front and back: Cronk Sumark [IOM 3220]. Credits: 1179 courtesy Ian Brown; 0664 courtesy James O’Driscoll; remainder Ian Ralston. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii -

Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning Behind Animal Burials

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning behind Animal Burials JAMES MORRIS The remains of animals, fragments of bone and horn, are often the most common finds recovered from archaeological excavations. The potential of using this mate- rial to examine questions of past economics and environment has long been recognized and is viewed by many archaeologists as the primary purpose of animal remains. In part this is due to the paradigm in which zooarchaeology developed and a consequence of prac- titioners’ concentration on taphonomy and quantification.1 But the complex intertwined relationships between humans and animals have long been recognized, a good example being Lévi-Strauss’s oft quoted “natural species are chosen, not because they are ‘good to eat’ but because they are ‘good to think.’”2 The relatively recent development of social zooarchae- ology has led to a more considered approach to the meanings and relationships animals have with past human cultures.3 Animal burials are a deposit type for which social, rather than economic, interpretations are of particular relevance. When animal remains are recovered from archaeological sites they are normally found in a state of disarticulation and fragmentation, but occasionally remains of an individual animal are found in articulation. These types of deposits have long been noted in the archaeological record, although their descriptions, such as “special animal deposit,”4 can be heavily loaded with interpretation. In Europe some of the earliest work on animal buri- als was Behrens’s investigation into the “Animal skeleton finds of the Neolithic and Early Metallic Age,” which discussed 459 animal burials from across Europe.5 Dogs were the most common species to be buried, and the majority of these cases were associated with inhumations. -

The Celts Free Download

THE CELTS FREE DOWNLOAD Dr. Alice Roberts | 320 pages | 18 Oct 2016 | Quercus Publishing | 9781784293321 | English | London, United Kingdom The History of Great Britain. The Celts in the British Isles (6th-3d B.C.) Part 3 In fact the Romans called these people Britonsnot Celts. Although this new form of Celtic identity is far removed from its prehistoric origins, it is The Celts testament to the powerful nature of this most distinctive and magnificent of ancient civilisations. Like other European Iron Age tribal societies, the Celts practised a polytheistic The Celts. Some scholars think that the Urnfield culture of western Middle Europe represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European family. However continued exposure to Anglo-Saxon influences resulted in the loss The Celts almost all the P-Celtic heritage except in a few place names. Much Greek and Roman literature has survived and it ought to be easy to pinpoint the Celts on their home ground. Celts and the Classical World. Diodorus Siculus and Strabo both suggest that the heartland of the people they called Celts was in southern France. The Celts of the most influential tribes, the Scordiscihad established their capital at Singidunum in the 3rd century BC, which is present-day BelgradeSerbia. Archived from the original on The Celts April For instance, the Irish god Lugh, associated with storms, lightningand culture, is seen in similar forms as Lugos in Gaul and Lleu in Wales. Our understanding of these tribes is incomplete, although their names — such as the Atrebates, Durotriges, Catuvellauni and Iceni — were recorded by the Romans. -

Display PDF in Separate

local environment agency plan WEST DORSET CONSULTATION REPORT NOVEMBER 1997 BLANDFORD FORUM National Information Centre The Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive Aztec West BRISTOL BSI2 4 UD Due for return FOREWORD • WEST DORSET LOCAL ENVIRONMENT AGENCY PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT Foreword This Plan is one of a series that is being prepared to cover the whole of England and Wales. Together they represent a significant step forward in environmental thinking. It has been clear for many years that the problems of land, air and water, particularly in the realms of pollution control, cannot be addressed individually. They are interdependant, each affecting the others. The Government's an swer was to create the Environment Agency with an umbrella responsibility for all three, and these Plans are one of the principal ways in which the Agency is approaching the task of bringing them together within an overall programme. * Like most of these Plans, this one covers very contrasting areas. The western part is basically rural while the eastern section is dominated by the more urban character of Weymouth and Portland. It does, however, differ from most in covering a number of small catchments rather than a single river. The issues covered in this Plan are central to the future quality of life for all the people who live in the area. They complement the work being done by the local authorities, and are strongly, allied to the environmental aims of the various Local Agenda 21 Groups. These Plans influence the'priorities of the Environment Agency in the area, and so must be of great importance to the growing number of people who are concerned for the environment So, do please read this document Think about its contents, discuss it with your colleagues, and let us know your conclusions.