COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS SUFFOLK, Ss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Thomas More Church Allentown, Pennsylvania

Saint Thomas More Church Allentown, Pennsylvania ©2012 Bon Venture Services, LLC ©2012Services, ©Bon | Deja Ursula Venture MASSES FOR THE WEEK OF DECEMBER 14, 2020 CATHOLIC BISHOP ABUSE REPORTING SERVICE MONDAY, December 14 If you have an allegation of abuse against a bishop, Saint John of the Cross please contact the Catholic Bishop Abuse Reporting Numbers 24:2-7, 15-17a; Matthew 21:23-27 Service at www.ReportBishopAbuse.org or by calling 7:00 a.m. Joseph Bobal 800-276-1562. 8:45 a.m. Bradley Perz PARISH REGISTRATION TUESDAY, December 15 New Parishioners are asked to register at the Rectory. Zephaniah 3:1-2, 9-13; Matthew 21:28-32 Please call first to make an appointment. You must be an 7:00 a.m. Eleanor Bialko active registered member of the parish for six months prior 8:45 a.m. Roseanne Vetter AND Jeanne Marie Warzeski to receiving a certificate of eligibility to be a sponsor for Baptism or Confirmation. Also, in regard to Marriage, WEDNESDAY, December 16 either the bride or groom must be registered and a Isaiah 45:6b-8, 18, 21c-25; Luke 7:18b-23 practicing member of the parish for at least six months. 7:00 a.m. Marie Mulik Please notify the Rectory if you change your address or 8:45 a.m. Barbara Przybylska move out of the parish. THURSDAY, December 17 PLEASE NOTE REGARDING HOSPITAL ADMISSION Genesis 49:2, 8-10; Matthew 1:1-17 If you or a loved one would be admitted to any of the local 7:00 a.m. -

Saint Thomas More Church Allentown, Pennsylvania

Respect Life Jesus loves the children of the world, the born and the unborn. Saint Thomas More Church Allentown, Pennsylvania ©2012 Bon Venture Services, LLC ©2012Services, Bon Venture MASSES FOR THE WEEK RELIGIOUS EDUCATION MONDAY, October 7 Grades: K-6: Sunday, 8:30-10:10 a.m., October 20 Jon 1:1-22, 11; Lk 10:25-37 Grades 7-8: Sunday, 8:30-10:10 a.m., October 20 7:00 a.m. Sally Thebege Grades 7-8: Monday, 7:30-9:00 p.m., October 21 8:45 a.m. Bud Landis Call 610-437-3491 with questions or to report absences. For cancellations, visit the STORMCENTER on WFMZ. TUESDAY, October 8 Jon 3:1-10; Lk 10:38-42 NEWLY BAPTIZED 7:00 a.m. Andrew J. O’Donnell Please welcome into our parish community Ashton 8:45 a.m. Paul Cera Alexander Zanchettin. We congratulate his parents! 5:30 p.m. Dr. and Mrs. Robert Biondi PARISH REGISTRATION WEDNESDAY, October 9 New Parishioners are asked to register at the Rectory. Jon 4:1-11; Lk 11:1-4 Please call first to make an appointment. You must be an 7:00 a.m. Bert Fantuzzi active registered member of the parish for six months prior 8:45 a.m. Lillian Pizza to receiving a certificate of eligibility to be a sponsor for 5:30 p.m. Clara Fioravanti Baptism or Confirmation. Also, in regard to Marriage, both THURSDAY, October 10 bride and groom must be registered and practicing Mal 3:13-20b; Lk 11:5-13 members for at least six months. -

Hello Pennsylvania

Hello Pennsylvania A QUICK TOUR OF THE COMMONWEALTH There is much to be proud of in Pennsylvania. Magnificent land, steadfast citizens, lasting traditions, resilient spirit — and a system of government that has sustained Pennsylvania and the nation for over 300 years. Hello Pennsylvania is one of a series of booklets we at the House of Representatives have prepared to make our state and the everyday workings of our government more understandable to its citizens. As your representatives, this is both our responsibility and our pleasure. Copies of this booklet may be obtained from your State Representative or from: The Office of the Chief Clerk House of Representatives Room 129, Main Capitol Building Harrisburg, PA 17120-2220 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA • HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES a hello Pennsylv marvelous mix A PENNSYLVANIA PROFILE A Quick Tour of the If you wanted to draw a 7 NORTHERN TIER Hunting, fishing, hardwood, Commonwealth picture of Pennsylvania and agriculture The largest open space in the Three hundred years ago, it Chances are you studied the you would need some facts. northeastern United States, this region houses the Little Like the size of the state Grand Canyon and more deer, was known as Penn’s Woods Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bear, and trout than people. and the kind of land and Counties: Bradford, Cameron, (Penn’s Sylvania) – and in a classroom years ago – or as Clinton, Elk, Forest, Lycoming, waterways that mark its McKean, Potter, Sullivan, William Penn owned it all! No recently as yesterday. But few Susquehanna, Tioga, Wyoming surface. You might want of us have Pennsylvania facts at 1 COLONIAL PENNSYLVANIA 4 ANTHRACITE AREA 8 STEEL KINGDOM commoner in history, before or to show major industries Historic attractions, high-tech, Recreation, manufacturing, Manufacturing, coal, high-tech, If you’ve got a good ear, education, and banking and coal and banking since, personally possessed our fingertips. -

Pennsylvania History

PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY VOL. XXI APRIL, 1954 No. 2 THE FAILURE OF THE "HOLY EXPERIMENT" IN PENNSYLVANIA, 1684-1699 By EDWIN B. BRONNER* HE founding of colonial Pennsylvania was a great success. TLet there be no misunderstanding in regard to that matter. The facts speak for themselves. From the very beginning colonists came to the Delaware Valley in great numbers. Philadelphia grew rapidly and was eventually the largest town in the British colonies. The area under cultivation expanded steadily; Pennsylvania con- tinued to grow throughout the colonial period, and her pecuniary success has never been questioned. The Proprietor granted his freemen an enlightened form of government, and gradually accepted a series of proposals by the citizenry for liberalizing the constitution. As an outgrowth of the Quaker belief that all men are children of God, the colony granted religious toleration to virtually all who wished to settle, made a practice of treating the Indians in a fair and just manner, opposed (as a matter of conscience) resorting to war, experimented with enlightened principles in regard to crime and punishment, and fostered advanced ideas concerning the equality of the sexes and the enslavement of human beings. As a colonizing venture, the founding of Pennsylvania was a triumph for William Penn and those who joined with him in the undertaking. On the other hand, conditions which prevailed in Pennsylvania in the first decades caused Penn untold grief, and results fell far short of what he had envisaged when he wrote concerning the *Dr. Edwin B. Bronner of Temple University is author of Thomas Earle as a Reformer and "Quaker Landmarks in Early Philadelphia" (in Historic Philadelphia, published by the American Philosophical Society, 1953). -

Pennsylvania Parent Guide to Special Education for School-Age Children

Pennsylvania Parent Guide to Special Education for School-Age Children INTRODUCTION Parents are very important participants in the special education process. Parents know their child better than anyone else and have valuable information to contribute about the kinds of programs and services that are needed for their child’s success in school. To ensure the rights of children with a disability, additional laws have been enacted. In this guide we use the terms “rules” and “regulations.” This booklet has been written to explain these rules so parents will feel comfortable and can better participate in the educational decision-making process for their child. The chapters that follow address questions that parents may have about special education, relating to their child who is thought to have, or may have, a disability. Chapter One focuses on how a child’s need for special education is determined. In this chapter, the evaluation and decision-making processes are discussed, as well as the members of the team who conduct the tests and make the decisions regarding a child’s eligibility for special education programs and services. Chapter Two explains how a special education program (that is, an Individualized Education Program) is devel- oped and the kinds of information it must include. This chapter describes how appropriate services are deter- mined, as well as the notice that a school district must give to parents summarizing a child’s special education program. Planning for the transition from school to adult living is also discussed. Chapter Three deals with the responsibilities that a school district has to a child who is eligible for special education services and the child’s parents. -

DCR's Beaver Brook Reservation

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Resource Management Planning Program RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts March 2010 DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010 Deval L. Patrick, Governor Timothy P. Murray, Lt. Governor Ian A. Bowles, Secretary Richard K. Sullivan, Jr., Commissioner Jack Murray, Deputy Commissioner for Parks Operations The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), an agency of the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, oversees 450,000 acres of parks and forests, beaches, bike trails, watersheds, dams, and parkways. Led by Commissioner Richard K. Sullivan Jr., the agency’s mission is to protect, promote, and enhance our common wealth of natural, cultural, and recreational resources. To learn more about DCR, our facilities, and our programs, please visit www.mass.gov/dcr. Contact us at [email protected]. Printed on Recycled Paper RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Expanded Beaver Brook Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 Planning Process 2 Distinctive Characteristics of the Expanded Reservation 2 Priority Findings 3 Recommendations 5 Capital Improvements 7 Land Stewardship Zoning Guidelines 9 Management -

Philadelphia County One of the Three Original Counties Created by William

Philadelphia County One of the three original counties created by William Penn in November 1682, and its name to him signified “brotherly love,” although the original Philadelphia in Asia Minor was actually “the city of Philadelphus.” Philadelphia was laid out in 1682 as the county seat and the capital of the Province; it was chartered as a city on October 25, 1701, and rechartered on March 11, 1789. On February 2, 1854, all municipalities within the county were consolidated with the city. The county offices were merged with the city government in 1952. Swedes and Finns first settled within the county in 1638. Dutch seized the area in 1655, but permanently lost control to England in 1674. Penn’s charter for Pennsylvania was received from the English king in 1681, and was followed by Penn’s November 1682 division of Pennsylvania into three counties. The City of Philadelphia merged (and became synonymous) with Philadelphia County in 1854. Thomas Holme made the physical plan for the City, and the Northern Liberties were designated to give urban lots to all who purchased 5,000 rural acres in Pennsylvania. The City had eighty families in 1683, 4,500 inhabitants in 1699, 10,000 in 1720, 23,700 in 1774. Philadelphia was economically the strongest city in America until surpassed by New York City in population in 1820 and in commerce by about 1830, although Philadelphia was strongest in manufacturing until the early twentieth century. It led the nation in textiles, shoes, shipbuilding, locomotives, and machinery. Leadership in transportation, both as a depot and a center for capital funding, was another Philadelphia attribute. -

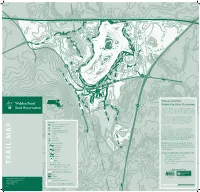

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

North Penn High School Student-Athlete Named Gatorade Pennsylvania Softball Player of the Year

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] NORTH PENN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT-ATHLETE NAMED GATORADE PENNSYLVANIA SOFTBALL PLAYER OF THE YEAR CHICAGO (June 18, 2021) — In its 36th year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, Gatorade today announced Mady Volpe of North Penn High School as its 2020-21 Gatorade Pennsylvania Softball Player of the Year. Volpe is the first Gatorade Pennsylvania Softball Player of the Year to be chosen from North Penn High School. The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Volpe as Pennsylvania’s best high school softball player. Now a finalist for the prestigious Gatorade National Softball Player of the Year award to be announced in June, Volpe joins an elite alumni association of state award-winners in 12 sports, including Cat Osterman (2000-01, Cy Spring High School, Texas), Kelsey Stewart (2009-10, Arkansas City High School, Kan.), Carley Hoover (2012-13, D.W. Daniel High School, S.C.), Jenna Lilley (2012-13, Hoover High School, Ohio), Morgan Zerkle (2012-13, Cabell Midland High School, W. Va.), and Rachel Garcia (2014-15, Highland High School, Calif.). The 5-foot-8 senior right-handed pitcher had led the Knights (24-2) to the Class 6A semifinals at the time of her selection. Volpe had posted a 24-2 record with a 0.73 ERA through 26 games, striking out 316 batters in 162 innings pitched. A two-time First Team All-State honoree and a three-time All-League selection, she also batted .309 with 22 RBI. -

A Timeline of Bucks County History 1600S-1900S-Rev2

A TIMELINE OF BUCKS COUNTY HISTORY— 1600s-1900s 1600’s Before c. A.D. 1609 - The native peoples of the Delaware Valley, those who greet the first European explorers, traders and settlers, are the Lenni Lenape Indians. Lenni Lenape is a bit of a redundancy that can be translated as the “original people” or “common people.” Right: A prehistoric pot (reconstructed from fragments), dating 500 B.C.E. to A.D. 1100, found in a rockshelter in northern Bucks County. This clay vessel, likely intended for storage, was made by ancestors of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley. Mercer Museum Collection. 1609 - First Europeans encountered by the Lenape are the Dutch: Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the Dutch flag, sailed up Delaware Bay. 1633 - English Captain Thomas Yong tries to probe the wilderness that will become known as Bucks County but only gets as far as the Falls of the Delaware River at today’s Morrisville. 1640 - Portions of lower Bucks County fall within the bounds of land purchased from the Lenape by the Swedes, and a handful of Swedish settlers begin building log houses and other structures in the region. 1664 - An island in the Delaware River, called Sankhickans, is the first documented grant of land to a European - Samuel Edsall - within the boundaries of Bucks County. 1668 - The first grant of land in Bucks County is made resulting in an actual settlement - to Peter Alrichs for two islands in the Delaware River. 1679 - Crewcorne, the first Bucks County village, is founded on the present day site of Morrisville. -

Examination of Health and Public Health Service Delivery in Delaware County, Pennsylvania

Final Report Examination of Health and Public Health Service Delivery in Delaware County, Pennsylvania July 20, 2020 Prepared by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, under contract with the Delaware County Council Principle Investigators Paulani Mui, MPH Beth Resnick, DrPH, MPH Aruna Chandran, MD, MPH Contributors: George Zhang, MPH Katherine Zellner, MPH 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................3 Background ................................................................................................................................9 Project Origins .................................................................................................................................... 9 Contextual Background ...................................................................................................................... 9 Approach and Methods .................................................................................................................... 10 Study Framework: The Core Public Health Functions & 10 Essential Public Health Services ......... 11 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Results ......................................................................................................................................19 Aim 1: Inventory of existing health and public health service structure........................................... -

Fish Population Sampling

2005 Deerfield River Watershed Fish Population Assessment Robert J. Maietta Watershed Planning Program Worcester, MA January, 2007 CN: 223.4 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ian Bowles, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Arleen O’Donnell, Acting Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Glenn Haas, Acting Assistant Commissioner Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Introduction Fish population surveys were conducted in the Deerfield River Watershed during the late summer of 2005 using techniques similar to Rapid Bioassessment Protocol V as described originally by Plafkin et al.(1989) and later by Barbour et al. (1999). Standard Operating Procedures are described in MassDEP Method CN 075.1 Fish Population SOP. Surveys also included a habitat assessment component modified from that described in the aforementioned document (Barbour et al. 1999). Fish populations were sampled by electrofishing using a Smith Root Model 12 battery powered backpack electrofisher. A reach of between 80m and 100m was sampled by passing a pole mounted anode ring, side to side through the stream channel and in and around likely fish holding cover. All fish shocked were netted and held in buckets. Sampling proceeded from an obstruction or constriction, upstream to an endpoint at another obstruction or constriction such as a waterfall or shallow riffle. Following completion of a sampling run, all fish were identified to species, measured, and released. Results of the fish population surveys can be found in Table 1. It should be noted that young of the year (yoy) fish from most species, with the exception of salmonids are not targeted for collection. Young-of-the-year fishes which are collected, either on purpose or inadvertently, are noted in Table 1.