Court Statistics for England and Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

Court Reform in England

Comments COURT REFORM IN ENGLAND A reading of the Beeching report' suggests that the English court reform which entered into force on 1 January 1972 was the result of purely domestic considerations. The members of the Commission make no reference to the civil law countries which Great Britain will join in an important economic and political regional arrangement. Yet even a cursory examination of the effects of the reform on the administration of justice in England and Wales suggests that English courts now resemble more closely their counterparts in Western Eu- rope. It should be stated at the outset that the new organization of Eng- lish courts is by no means the result of the 1971 Act alone. The Act crowned the work of various legislative measures which have brought gradual change for a period of well over a century, including the Judicature Acts 1873-75, the Interpretation Act 1889, the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925, the Administration of Justice Act 1933, the County Courts Act 1934, the Criminal Appeal Act 1966 and the Criminal Law Act 1967. The reform culminates a prolonged process of response to social change affecting the legal structure in England. Its effect was to divorce the organization of the courts from tradition and history in order to achieve efficiency and to adapt the courts to new tasks and duties which they must meet in new social and economic conditions. While the earlier acts, including the 1966 Criminal Appeal Act, modernized the structure of the Supreme Court of Judicature, the 1971 Act extended modern court structure to the intermediate level, creating the new Crown Court, and provided for the regular admin- istration of justice in civil matters by the High Court in England and Wales, outside the Royal Courts in London. -

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Report 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Common abbreviations used in this report are set out below. Local abbreviations are explained in the report. ABM Area Business Manager HMCPSI Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate ABP Area Business Plan JDA Judge Directed Acquittal AEI Area Effectiveness Inspection JOA Judge Ordered Acquittal ASBO Anti-Social Behaviour Order JPM Joint Performance Monitoring BCU Basic Command Unit or Borough Command Unit LCJB Local Criminal Justice Board BME Black and Minority Ethnic MAPPA Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements CCP Chief Crown Prosecutor MG3 Form on which a record of the CJA Criminal Justice Area charging decision is made CJS Criminal Justice System NCTA No Case to Answer CJSSS Criminal Justice: Simple, Speedy, NRFAC Non Ring-Fenced Administrative Summary Costs CJU Criminal Justice Unit NWNJ No Witness No Justice CMS Case Management System OBTJ Offences Brought to Justice CPIA Criminal Procedure and OPA Overall Performance Assessment Investigations Act PCD Pre-Charge Decision CPO Case Progression Officer PCMH Plea and Case Management Hearing CPS Crown Prosecution Service POCA Proceeds of Crime Act CPSD CPS Direct PTPM Prosecution Team Performance CQA Casework -

Request for Transcription of Court Or Tribunal Proceedings

EX107GN Guidance Notes – Request for Transcription of Court or Tribunal proceedings If you want a transcript of proceedings in any court or tribunal (except the Court of Appeal Criminal Division or the Administrative Court*), please complete form EX107. If you want to order a transcript for more than one case, please complete a separate form EX107 for each different case in which you’re interested. Please note that not all Tribunals record proceedings so transcription services may not be available. Enquiries should be made to the relevant tribunal prior to completion of this form. EX107 can be sent digitally or by post to the court or tribunal. Contract details for the relevant venue can be obtained via Court Finder at https://courttribunalfinder.service.gov.uk/search/ For Civil and Family jurisdictions where you are selecting a transcription company, you are advised to talk with the transcription company before you complete form EX107. If an EX107 is requested by your chosen transcription company this should, where possible, be sent digitally using the e-mail addresses in Section 2a. You may send by post if you do not have an e-mail account. There may be occasions where a transcript you have requested via the EX107 may have already been produced for HMCTS. There may also be times where the court’s authorised Transcription Company provided a stenographer or court logger to make a record of the proceedings. In these circumstances the court’s authorised Transcription Company will provide the transcript and the court will tell you who to contact. Where a transcript is required of a court hearing which was held in private (ex parte) the process will vary by jurisdiction as follows: a) In cases heard at the Royal Courts of Justice and Crown Courts and some tribunals (or if the Court so orders at other venues), where a transcript is required of Court proceedings which were officially designated by the judge as being held in private (ex-parte), authorisation will be required from a Judge. -

[email protected]

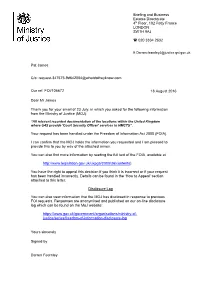

Briefing and Business Estates Directorate 4th Floor, 102 Petty France LONDON SW1H 9AJ 020 3334 2632 E [email protected] Pat James C/o: [email protected] Our ref: FOI/106672 18 August 2016 Dear Mr James Thank you for your email of 23 July, in which you asked for the following information from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ): “All relevant recorded documentation of the locations within the United Kingdom where G4S provide 'Court Security Officer' services to HMCTS”. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). I can confirm that the MOJ holds the information you requested and I am pleased to provide this to you by way of the attached annex. You can also find more information by reading the full text of the FOIA, available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/36/contents). You have the right to appeal this decision if you think it is incorrect or if your request has been handled incorrectly. Details can be found in the ‘How to Appeal’ section attached to this letter. Disclosure Log You can also view information that the MOJ has disclosed in response to previous FOI requests. Responses are anonymised and published on our on-line disclosure log which can be found on the MoJ website: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ministry-of- justice/series/freedom-of-information-disclosure-log Yours sincerely Signed by Darren Fearnley Annex HMCTS sites where security is provided by G4S Building Name Address Aberdeen Tribunal Atholl House, 84-86 Guild Street, Aberdeen -

Change at Lewes Crown Court

News from the South Eastern Circuit THE CIRCUITEER INSIDE THIS ISSUE 8 9 10 12 19 Meeting of the Inns of Court John Downes 23rd Keble A view from the Chairs of the College of Alliot a tribute Course Naval Bar SEC Bar Messes Advocacy (ICCA) ALL CHANGE AT LEADER’S LEWES CROWN REPORT And so, the time has come for me to bid farewell as Leader of COURT this great Circuit. 2016 has been a time of change across Max Hill QC See page 3 the whole of the Criminal Justice System. Lewes Crown Court has seen significant change, with its three most experienced judges retiring in the space of a few months. See page 6 Wellbeing at the Bar Does our wellbeing depend on the respite we all seek to find in holidays or should it be more a part of our daily lives even whilst working. Valerie Charbit See page 22 Reflections of a Circuiteer CIRCUIT TRIP TO PARIS I was called to the Bar in 1963. To practice It has been a number of years since the last circuit trip, and at what was then called the Independent many more since the last to Paris. This diplomatic mission Bar, whether you intended to venture out was long overdue, and, as we discovered from the moment of London or not, you were required to we arrived, a venture enthusiastically welcomed by our join a Circuit. Parisian counterparts. See page 14 See page 5 Igor Judge THE CIRCUITEER Issue 42 / October 2016 1 News from the South Eastern Circuit EDITOR’S COLUMN Much has happened across or friends, we are reminded • 88% of trans people have the Circuit since the Spring of the transient nature of our experienced depression edition, with changes of flickering flames. -

A Barrister's Role in the Plea Decision

A Barrister’s Role in the Plea Decision: An analysis of drivers affecting advice in the Crown Court By James Dominic Edward Barry Queen Mary, University of London Submitted for PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own …………………………………. Date: ……………………………. James D.E Barry 2 Abstract: This thesis explores the reasons behind barristers' advice to defendants in the Crown Court on plea, primarily through interviews with criminal law practitioners themselves. Beginning with a critical overview of the current research, the thesis argues that the views of criminal barristers are a neglected significant source of information in developing an understanding of why particular advice is given. The thesis, in the context of other research, analyses the data from interviews conducted with current practitioners on the London and the Midlands Circuits, and discusses the various drivers that act upon barristers in deciding what advice to give. Starting with the actual advice given and the advising styles adopted, the thesis explores why guilty pleas might be advised and plea bargains sought with prosecutors. The research goes on to examine the impact of various influences, including legal, ethical, cultural, regional and financial to produce an overview of what factors impact upon a barrister's advice. The thesis argues that the current view of the Bar sustained in much of the literature is insufficiently nuanced and outdated, and that the reasons behind the advice given to defendants on plea are extraordinarily varied, occasionally contradictory, and highly complex. The thesis concludes that the data from the interviews warrants a rethink of why particular advice is given and that discovering what drives barristers’ advice is critical to formulating law and government policy. -

The High Court's Jurisdiction in Relation to Criminal

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 184 THE HIGH COURT’S JURISDICTION IN RELATION TO CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS A Consultation Paper The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Etherton, Chairman Mr Stuart Bridge Mr David Hertzell Professor Jeremy Horder Kenneth Parker QC Professor Martin Partington CBE is Special Consultant to the Law Commission responsible for housing law reform. The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Steve Humphreys and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. This consultation paper, completed on 1 October 2007, is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on its proposals before 22 February 2008. Comments may be sent either – By post to: David Hughes Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WC1N 2BQ Tel: 020-7453-1212 Fax: 020-7453-1297 By email to: [email protected] It would be helpful if, where possible, comments sent by post could also be sent on disk, or by email to the above address, in any commonly used format. We will treat all responses as public documents in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act and we may attribute comments and include a list of all respondents' names in any final report we publish. Those who wish to submit a confidential response should contact the Commission before sending the response. -

Rebecca Upton Call: 1999

Rebecca Upton Call: 1999 Rebecca Upton practises primarily in the Crown Courts of the South East of England. She also has significant experience in the Court of Appeal, civil and criminal applications made by the police and inquests. ‘She is a very meticulous advocate with a very thorough preparation process.’ Legal 500 2021 “She’s very good at adapting her style to the case she’s handling.” Chambers & Partners 2020 “She is always thoroughly prepared and has a very good rapport with other advocates and judges.” Legal 500 2019 Crime Rebecca has built up a strong criminal practice and undertakes work in all areas of criminal law including murder, manslaughter, death by dangerous / careless driving and other motoring offences, serious violence, sexual offences (including rape and possession of indecent images), drugs, fraud and arson. Rebecca has been led many times and has also been instructed as leading junior. She is often involved in multi handed cases, including conspiracies. Rebecca also has experience in Courts Martial, Environment Agency, Inquest and RSPCA cases, and advises and appears in the Court of Appeal. T: +44 (0)1273 625 625 [email protected] www.1cor.com Rebecca has particular experience in advising on the need for psychiatric / psychological reports and calling expert witnesses. She also has regular cases dealing with vulnerable clients and witnesses, including those who need intermediaries, and those who are very young or mentally unwell. Selected Cases R v JM (2021) Lewes CC: defended JM who was charged with sexual offences against 2 strangers on the same night. R v CC (2021) Lewes CC: junior counsel, CC was accused of murdering his girlfriend whilst they were on a camping trip. -

Faulty Adversarial Performance by Criminal Defenders in the Crown Court

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2001 Faulty Adversarial Performance by Criminal Defenders in the Crown Court Peter W. Tague Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/241 12 King's C. L.J. 137-173 (2001) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications February 2010 Faulty Adversarial Performance by Criminal Defenders in the Crown Court 12 King’s C. L.J. 137-173 (2001) Peter W. Tague Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/241/ Posted with permission of the author (2001) 12 KCL] 137 PETER W. TAGUE* FAULTY ADVERSARlAL PERFORMANCE BY CRIMINAL DEFENDERS IN THE CROWN COURT " x THO IS the more able advocate, the lawyer in the United States or the barrister V V in England and Wales?! Answering that question is extremely difficult because of a multitude of differences in the procedural regimes in which each works and in the scope of each's responsibility.2 Yet, one facet stands out, like a full moon in a dark sky: The comparative number of defenders who on appeal have been accused ofhav ing provided inappropriate representation in the process leading to conviction. -

Written Evidence from the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales 1

Written evidence from the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales 1. The Committee has identified a number of particular issues it wishes to consider in connection with court capacity and the impact of the Covid emergency. Sitting days 2. The “sitting day” is the unit of currency which has been used historically to determine the provision of resources in all jurisdictions. In particular, staffing levels follow sitting day allocations. As is well known, in the two financial years leading up to April 2020, there were very substantial cuts in the sitting days in the Crown Courts. During the course of 2019 it became clear that the volume of outstanding cases in the Crown Court was rising and so additional sitting days were agreed by the Lord Chancellor at the end of 2019. In Civil and Family, in broad terms, the sitting day allocation was designed to match the likely availability of judicial resources, that is both salaried and fee-paid judges. Volumes of work in both the County Court and the Family Court were increasing before Covid engulfed the nation. Sitting days, or more accurately sessions, in the Magistrates’ Court, were adequate to deal with the volumes of work flowing through that court. 3. During the initial lockdown from March 2020, and in the months that have followed, the position in all jurisdictions is that as much work as it has been possible to do consistently with social distancing and available technology, has been done. 4. The Lord Chancellor and I have agreed that sitting days are not a constraint in any jurisdiction for the remainder of this financial year. -

The Student's Guide to the Leading Law Firms And

2021 The student’s guide to the leading law firms and sets in the UK e-Edition chambers-student.com Connect with us on cbaK Travers Smith is everything you could want from a law firm. First-rate training and market-leading work alongside some of the City’s finest lawyers. Prestigious clients. The opportunity to progress. And all in a supportive, non-hierarchical and inclusive environment. www.traverssmith.com 10 Snow Hill, London EC1A 2AL +44 (0) 20 7295 3000 Chambers Reports Atkin Chambers p.662 Littleton Chambers p.740 2 Bedford Row p.664 Maitland Chambers p.744 Blackstone Chambers p.668 Matrix Chambers p.748 Brick Court Chambers p.672 Monckton Chambers p.752 Cloisters Chambers p.676 4 New Square p.754 Crown Office Chambers p.680 No5 Barristers’ Chambers p.758 Devereux p.683 XXIV Old Buildings p.761 Erskine Chambers p.687 Outer Temple Chambers p.764 One Essex Court p.691 4 Pump Court p.768 5 Essex Court p.694 Pump Court Tax Chambers p.772 Essex Court Chambers p.696 Quadrant Chambers p.776 Falcon Chambers p.700 Queen Elizabeth Building QEB p.780 Farrar’s Building p.703 Radcliffe Chambers p.783 Fountain Court Chambers p.707 Serle Court p.786 Francis Taylor Building p.711 South Square p.790 Hailsham Chambers p.714 St Philips Chambers p.794 1 Hare Court p.718 4 Stone Buildings p.797 Henderson Chambers p.721 Tanfield Chambers p.801 11KBW p.724 2 Temple Gardens p.804 Keating Chambers p.728 3 Verulam Buildings p.808 7 King’s Bench Walk p.732 Wilberforce Chambers p.812 Landmark Chambers p.736 chambersstudent.co.uk Chambers Reports Chambers Reports Choosing where to apply for pupillage is hard.