Barristers ' Clerks the Law's Middlemetr John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Ireland Prepared by Lex Mundi Member Firm, Arthur Cox

Guide to Doing Business Northern Ireland Prepared by Lex Mundi member firm, Arthur Cox This guide is part of the Lex Mundi Guides to Doing Business series which provides general information about legal and business infrastructures in jurisdictions around the world. View the complete series at: www.lexmundi.com/GuidestoDoingBusiness. Lex Mundi is the world’s leading network of independent law firms with in-depth experience in 100+ countries. Through close collaboration, our member firms are able to offer their clients preferred access to more than 21,000 lawyers worldwide – a global resource of unmatched breadth and depth. Lex Mundi – the law firms that know your markets. www.lexmundi.com Lex Mundi: A Guide to Doing Business in Northern Ireland. Prepared by Arthur Cox Updated June 2016 This document is intended merely to highlight issues for general information purposes only. It is not comprehensive nor does it provide legal advice. Any and all information is subject to change without notice. No liability whatsoever is accepted by Arthur Cox for any action taken in reliance on the information herein. LEX MUNDI: A GUIDE TO DOING BUSINESS IN NORTHERN IRELAND, PREPARED BY ARTHUR COX PAGE 2 Contents I. THE COUNTRY AT-A-GLANCE ............................................................................................................. 4 A. What languages are spoken? ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 B. What is the exchange -

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Middle Society Honourable the The of 2019 Issue 59 Michaelmas 2019 Issue 59 Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales Practice Note (Relevance of Law Reporting) [2019] ICLR 1 Catchwords — Indexing of case law — Structured taxonomy of subject matter — Identification of legal issues raised in particular cases — Legal and factual context — “Words and phrases” con- strued — Relevant legislation — European and International instruments The common law, whose origins were said to date from the reign of King Henry II, was based on the notion of a single set of laws consistently applied across the whole of England and Wales. A key element in its consistency was the principle of stare decisis, according to which decisions of the senior courts created binding precedents to be followed by courts of equal or lower status in later cases. In order to follow a precedent, the courts first needed to be aware of its existence, which in turn meant that it had to be recorded and published in some way. Reporting of cases began in the form of the Year Books, which in the 16th century gave way to the publication of cases by individual reporters, known collectively as the Nominate Reports. However, by the middle of the 19th century, the variety of reports and the variability of their quality were such as to provoke increasing criticism from senior practitioners and the judiciary. The solution proposed was the establishment of a body, backed by the Inns of Court and the Law Society, which would be responsible for the publication of accurate coverage of the decisions of senior courts in England and Wales. -

OUTLINE KD51-9500 Law of England and Wales KD51-59 Bibliography

OUTLINE KD51-9500 Law of England and Wales KD51-59 Bibliography KD62 Official gazettes KD124-180 Legislation KD124-150 Statues KD166-173 Subordinate (Delegated legislation) KD175-180 Prerogative legislation KD187-300 Law reports and related materials KD310 Encyclopedias KD313 Law dictionaries. Words and phrases KD315 Legal maxims. Quotations KD318 Form books KD327-332 Judicial statistics KD336-340 Directories KD345 Society and bar association journals KD347 Congresses KD353-358 Collections KD370-379.5 Trials KD370-376 Criminal trials and judicial investigations KD378-379.5 Civil trials KD392-400 Legal research. Legal bibliography KD404 Legal composition and draftsmanship KD411 Law reporting. Law reporters KD417-452 Legal education KD456 Law societies KD460-510 The legal profession KD512-513 Community legal services. Legal aid KD530-632 History KD640 Jurisprudence and philosophy of English law KD654 Criticism. Legal reform. General administration of justice KD658-669 General and comprehensive works KD671 Common law KD674 Equity KD680-685 Conflict of laws KD687 Retroactive law. Intertemporal law KD691-700 General principles and concepts KD703 Concepts applying to several branches of law KD720-721 Private (Civil) law KD723-785 Persons KD723-746 General. Status. Capacity KD750-785 Domestic relations. Family law vii OUTLINE Law of England and Wales - Continued KD810-1465 Property KD810-815 General. Ownership. Possession KD821-1195 Real property. Land law KD833-1020.6 Land tenure. Transfer of rights in land. Real estate management KD1034-1195 Public property. Public restraints on private property KD1035 Conservation of natural resources KD1040-1048 Roads KD1070-1072 Water resources. Rivers. Water courses KD1090-1107 Public land law KD1125-1162 Regional and city planning. -

Principles of Administrative Law 1

CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD PRINCIPLES OF LAW SERIES Professor Paul Dobson Visiting Professor at Anglia Polytechnic University Professor Nigel Gravells Professor of English Law, Nottingham University Professor Phillip Kenny Professor and Head of the Law School, Northumbria University Professor Richard Kidner Professor and Head of the Law Department, University of Wales, Aberystwyth In order to ensure that the material presented by each title maintains the necessary balance between thoroughness in content and accessibility in arrangement, each title in the series has been read and approved by an independent specialist under the aegis of the Editorial Board. The Editorial Board oversees the development of the series as a whole, ensuring a conformity in all these vital aspects. David Stott, LLB, LLM Deputy Head, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University Alexandra Felix, LLB, LLM Lecturer in Law, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney First published in Great Britain 1997 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX. Telephone: 0171-278 8000 Facsimile: 0171-278 8080 e-mail: [email protected] Visit our Home Page on http://www.cavendishpublishing.com © Stott, D and Felix, A 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

Northern Irish Legal Education After Brexit

Northern Irish Legal Education After Brexit Flear, M. L., & Mac Sithigh, D. (2019). Northern Irish Legal Education After Brexit. The Law Teacher, 53(2), 148- 159. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069400.2019.1589745 Published in: The Law Teacher Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2019 The Association of Law Teachers. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Northern Irish Legal Education after Brexit Mark L Flear and Daithí Mac Síthigh* In this article we argue that the impact of Brexit on the law schools in Northern Ireland is tied to the ‘unique circumstances’ of legal education in this part of the world. Legal education in Northern Ireland is likely to develop to become even more distinctive than that in other parts of the UK. -

Court Reform in England

Comments COURT REFORM IN ENGLAND A reading of the Beeching report' suggests that the English court reform which entered into force on 1 January 1972 was the result of purely domestic considerations. The members of the Commission make no reference to the civil law countries which Great Britain will join in an important economic and political regional arrangement. Yet even a cursory examination of the effects of the reform on the administration of justice in England and Wales suggests that English courts now resemble more closely their counterparts in Western Eu- rope. It should be stated at the outset that the new organization of Eng- lish courts is by no means the result of the 1971 Act alone. The Act crowned the work of various legislative measures which have brought gradual change for a period of well over a century, including the Judicature Acts 1873-75, the Interpretation Act 1889, the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925, the Administration of Justice Act 1933, the County Courts Act 1934, the Criminal Appeal Act 1966 and the Criminal Law Act 1967. The reform culminates a prolonged process of response to social change affecting the legal structure in England. Its effect was to divorce the organization of the courts from tradition and history in order to achieve efficiency and to adapt the courts to new tasks and duties which they must meet in new social and economic conditions. While the earlier acts, including the 1966 Criminal Appeal Act, modernized the structure of the Supreme Court of Judicature, the 1971 Act extended modern court structure to the intermediate level, creating the new Crown Court, and provided for the regular admin- istration of justice in civil matters by the High Court in England and Wales, outside the Royal Courts in London. -

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Report 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Common abbreviations used in this report are set out below. Local abbreviations are explained in the report. ABM Area Business Manager HMCPSI Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate ABP Area Business Plan JDA Judge Directed Acquittal AEI Area Effectiveness Inspection JOA Judge Ordered Acquittal ASBO Anti-Social Behaviour Order JPM Joint Performance Monitoring BCU Basic Command Unit or Borough Command Unit LCJB Local Criminal Justice Board BME Black and Minority Ethnic MAPPA Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements CCP Chief Crown Prosecutor MG3 Form on which a record of the CJA Criminal Justice Area charging decision is made CJS Criminal Justice System NCTA No Case to Answer CJSSS Criminal Justice: Simple, Speedy, NRFAC Non Ring-Fenced Administrative Summary Costs CJU Criminal Justice Unit NWNJ No Witness No Justice CMS Case Management System OBTJ Offences Brought to Justice CPIA Criminal Procedure and OPA Overall Performance Assessment Investigations Act PCD Pre-Charge Decision CPO Case Progression Officer PCMH Plea and Case Management Hearing CPS Crown Prosecution Service POCA Proceeds of Crime Act CPSD CPS Direct PTPM Prosecution Team Performance CQA Casework -

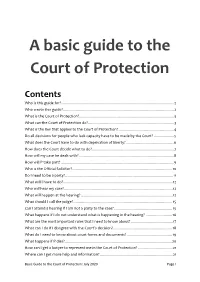

A Basic Guide to the Court of Protection

A basic guide to the Court of Protection Contents Who is this guide for? ................................................................................................................ 2 Who wrote this guide? .............................................................................................................. 2 What is the Court of Protection? .............................................................................................. 3 What can the Court of Protection do? ..................................................................................... 3 What is the law that applies to the Court of Protection? ....................................................... 4 Do all decisions for people who lack capacity have to be made by the Court? .................... 5 What does the Court have to do with deprivation of liberty? ................................................ 6 How does the Court decide what to do? ................................................................................. 7 How will my case be dealt with? .............................................................................................. 8 How will P take part? ................................................................................................................ 9 Who is the Official Solicitor? ................................................................................................... 10 Do I need to be a party? ........................................................................................................... 11 -

4 PAPER BUILDINGS Court of Protection Seminar

4 PAPER BUILDINGS Court of Protection Seminar 5th May 2011 CHAIR Robin Barda TOPICS & SPEAKERS : Court of Protection - Welfare Sally Bradley The Property and Affairs of Mentally Incapacitated Adults: Cases of Interest Following The Coming Into Force of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 James Copley A Mediation process for Court of Protection Matters Angela Lake-Carroll The Chambers of Jonathan Cohen QC INDEX 1. 4 Paper Buildings: Who we are 2. Court of Protection - Welfare Sally Bradley 3. The Property and Affairs of Mentally Incapacitated Adults: -Cases of Interest Following The Coming Into Force of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 James Copley 4. A Mediation process for Court of Protection Matters Angela Lake-Carroll 5. Court of Protection Handout & Crib Sheet (notes only) Henry Clayton 6. Profiles of the speakers 7. Members of Chambers Section 1 4 Paper Buildings: Who we are The Chambers of Jonathan Cohen QC 4 Paper Buildings “This dedicated family set has expanded rapidly in recent years and now has a large number of the leading players in the field.” Chambers UK 2010 At 4 Paper Buildings, Head of Chambers Jonathan Cohen QC has 'developed a really strong team across the board'. 'There is now a large number of specialist family lawyers who provide a real in-depth service on all family matters.' The 'excellent' 4 Paper Buildings 'clerks are very helpful' and endeavor to solve problems, offering quality alternatives if the chosen counsel is not available.' Legal 500 2010 “4 Paper Buildings covers a broad spectrum of civil and family matters. On the family front its best known for its children- related work, although its reputation does extend to matrimonial finance work as well”. -

Request for Transcription of Court Or Tribunal Proceedings

EX107GN Guidance Notes – Request for Transcription of Court or Tribunal proceedings If you want a transcript of proceedings in any court or tribunal (except the Court of Appeal Criminal Division or the Administrative Court*), please complete form EX107. If you want to order a transcript for more than one case, please complete a separate form EX107 for each different case in which you’re interested. Please note that not all Tribunals record proceedings so transcription services may not be available. Enquiries should be made to the relevant tribunal prior to completion of this form. EX107 can be sent digitally or by post to the court or tribunal. Contract details for the relevant venue can be obtained via Court Finder at https://courttribunalfinder.service.gov.uk/search/ For Civil and Family jurisdictions where you are selecting a transcription company, you are advised to talk with the transcription company before you complete form EX107. If an EX107 is requested by your chosen transcription company this should, where possible, be sent digitally using the e-mail addresses in Section 2a. You may send by post if you do not have an e-mail account. There may be occasions where a transcript you have requested via the EX107 may have already been produced for HMCTS. There may also be times where the court’s authorised Transcription Company provided a stenographer or court logger to make a record of the proceedings. In these circumstances the court’s authorised Transcription Company will provide the transcript and the court will tell you who to contact. Where a transcript is required of a court hearing which was held in private (ex parte) the process will vary by jurisdiction as follows: a) In cases heard at the Royal Courts of Justice and Crown Courts and some tribunals (or if the Court so orders at other venues), where a transcript is required of Court proceedings which were officially designated by the judge as being held in private (ex-parte), authorisation will be required from a Judge.