Respondeat Superior in the Light of Comparative Law Robert Neuner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's Reasonable?: Self-Defense and Mistake in Criminal and Tort

Do Not Delete 12/15/2010 10:20 PM WHAT’S REASONABLE?: SELF-DEFENSE AND MISTAKE IN CRIMINAL AND TORT LAW by Caroline Forell∗ In this Article, Professor Forell examines the criminal and tort mistake- as-to-self-defense doctrines. She uses the State v. Peairs criminal and Hattori v. Peairs tort mistaken self-defense cases to illustrate why application of the reasonable person standard to the same set of facts in two areas of law can lead to different outcomes. She also uses these cases to highlight how fundamentally different the perception of what is reasonable can be in different cultures. She then questions whether both criminal and tort law should continue to treat a reasonably mistaken belief that deadly force is necessary as justifiable self-defense. Based on the different purposes that tort and criminal law serve, Professor Forell explains why in self-defense cases criminal law should retain the reasonable mistake standard while tort law should move to a strict liability with comparative fault standard. I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1402 II. THE LAW OF SELF-DEFENSE ................................................... 1403 III. THE PEAIRS MISTAKE CASES .................................................. 1406 A. The Peairs Facts ..................................................................... 1408 B. The Criminal Case .................................................................. 1409 1. The Applicable Law ........................................................... 1409 -

Respondeat Superior Principle to Assign Responsibility for Worker Statutory Benefits and Protections Michael Harper Boston University School of Law

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 11-13-2017 Using the Anglo-American Respondeat Superior Principle to Assign Responsibility for Worker Statutory Benefits and Protections Michael Harper Boston University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Common Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Harper, Using the Anglo-American Respondeat Superior Principle to Assign Responsibility for Worker Statutory Benefits na d Protections, Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research Paper Series (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/286 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING THE ANGLO‐AMERICAN RESPONDEAT SUPERIOR PRINCIPLE TO ASSIGN RESPONSIBILITY FOR WORKER STATUTORY BENEFITS AND PROTECTIONS Michael C. Harper* Introduction The common law remains an intellectual battle ground in Anglo‐ American legal systems, even in the current age of statutes. This is true in significant part because the common law provides legitimacy for arguments actually based on policy, ideology, and interest. It also is true because of the common law’s malleability and related susceptibility to significantly varied interpretations. Mere contention over the meaning of the common law to provide legitimacy for modern statutes is usually not productive of sensible policy, however. It generally produces no more than reified doctrine unsuited for problems the common law was not framed to solve. -

The Morality of Strict Liability

THE MORALITY OF STRICT TORT LIABILITY JULES L. COLEMAN* Accidents occur; personal property is damaged and sometimes is lost altogether. Accident victims are likely to suffer anything from mere bruises and headaches to temporary or permanent disability to death. The personal and social costs of accidents are staggering. Yet the question of who should bear these costs has turned the heads of few philosophers and has occasioned surprisingly little philo- sophic discussion. Perhaps that is because the answer has seemed so obvious; accident costs, at least the nontrivial ones, ought to be borne by those at fault in causing them.' The requirement of fault at one time appeared to be so deeply rooted in the concept of per- sonal responsibility that in the famous Ives2 case, Judge Werner was moved to argue that liability without fault was not only immoral, but also an unconstitutional violation of due process of law. Al- * Ph.D., The Rockefeller University; M.S.L., Yale Law School. Associate Professor of Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The author wishes to acknowledge the enormous impact that Joel Feinberg and Guido Calabresi have had on the philosophic and legal ideas set forth in this Article, and to express appreciation to Mitchell Polinsky, Bruce Ackerman, and Robert Prichard for their valuable assistance. This Article constitutes part of the author's forthcoming book, RESPONSIBIITY AND Loss ALLOCATION OF THE LAW OF TORTS (Ed.). 1. The term "fault" takes on different shades of meaning, depending upon the legal context in which it is used. For example, the liability of an intentional or reckless tortfeasor is determined differently from that of a negligent tortfeasor. -

The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: an Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1987 The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines Alan O. Sykes Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan O. Sykes, "The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines," 101 Harvard Law Review 563 (1987). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 101 JANUARY 1988 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW1 ARTICLES THE BOUNDARIES OF VICARIOUS LIABILITY: AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE SCOPE OF EMPLOYMENT RULE AND RELATED LEGAL DOCTRINES Alan 0. Sykes* 441TICARIOUS liability" may be defined as the imposition of lia- V bility upon one party for a wrong committed by another party.1 One of its most common forms is the imposition of liability on an employer for the wrong of an employee or agent. The imposition of vicarious liability usually depends in part upon the nature of the activity in which the wrong arises. For example, if an employee (or "servant") commits a tort within the ordinary course of business, the employer (or "master") normally incurs vicarious lia- bility under principles of respondeat superior. If the tort arises outside the "scope of employment," however, the employer does not incur liability, absent special circumstances. -

Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts

University of Miami Law Review Volume 14 Number 4 Article 8 7-1-1960 Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts Edwin C. Ratiner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Edwin C. Ratiner, Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts, 14 U. Miami L. Rev. 634 (1960) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol14/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUNICIPAL TORT LIABILITY-"QUASI JUDICIAL" ACTS Plaintiff, in an action against a municipality for false imprisonment, alleged that lie was arrested by a municipal police officer pursuant to a warrant known to be void by the arresting officer and the municipal court clerk who acted falsely in issuing the warrant. Held: because the acts alleged were "quasi judicial" in nature, the municipality was not liable under the doctrine of respondeat superior. Middleton Y. City of Fort Walton Beach, 113 So.2d 431 (Fla. App. 1959). The courts uniformly agree that the tortious conduct of a public officer committed in the exercise of a "judicial" or "quasi judicial"' function shall not render either the officer or his municipal employer liable.2 The judiciary of superior and inferior courts are generally accorded immunity from civil liability arising from judicial acts and duties performed within the scope of the court's jurisdiction. -

Chapter 8 Liability Based on Agency and Respondeat Superior A. Definitions

CHAPTER 8 LIABILITY BASED ON AGENCY AND RESPONDEAT SUPERIOR A. DEFINITIONS 8:1 Agency Relationship — Defined 8:2 Disclosed or Unidentified Principal — Defined 8:3 Undisclosed Principal — Defined 8:4 Employer and Employee — Defined 8:5 Independent Contractor — Definition 8:6 Loaned Employee 8:7 Loaned Employee ― Determination 8:8 Scope of Employment of Employee — Defined 8:9 Scope of Authority of Agent — Defined 8:9A Actual Authority 8:9B Express Authority 8:10 Incidental Authority — Defined 8:11 Implied Authority — Defined 8:12 Apparent Authority (Agency by Estoppel) — Definition and Effect 8:13 Scope of Authority or Employment — Departure 8:14 Ratification — Definition and Effect 8:15 Knowledge of Agent Imputable to Principal 8:16 Termination of Agent’s Authority 8:17 Termination of Agent’s Authority — Notice to Third Parties B. LIABILITY ARISING FROM AGENCY AND RESPONDEAT SUPERIOR 8:18 Principal and Agent or Employer and Employee — Both Parties Sued — Issue as to Relationship and Scope of Authority or Employment — Acts of Agent or Employee as Acts of Principal or Employer 8:19 Principal and Agent or Employer and Employee — Only Principal or Employer Sued — No Issue as to Relationship — Acts of Agent or Employee as Acts of Principal or Employer 8:20 Principal and Agent or Employer and Employee — Only Principal or Employer Sued — Issue as to Relationship and/or Scope of Authority or Employment — Acts of Agent or Employee as Acts of Principal or Employer 8:21 Principal and Agent or Employer and Employee — Both Parties Sued — Liability of Principal or Employer When No Issue as to Relationship or Scope of Authority or Employment 8:22 Principal and Agent or Employer and Employee — Both Parties Sued — Liability When Issue as to Relationship and/or Scope of Authority or Employment 8:23 Act of Corporate Officer or Employee as Act of Corporation 2 A. -

A Critique of Vicarious Liability in the Medical Malpractice Context

THE BUCK STOPS WHERE? A CRITIQUE OF VICARIOUS LIABILITY IN THE MEDICAL MALPRACTICE CONTEXT C. J. COLWELL† In Canadian tort law, liability is almost always linked to some notion of fault, save for a few well-established exceptions. By far the most common exception is vicarious liability, i.e. the liability of employers for the torts of their employees. In its 1999 ruling in Bazley v. Curry, the Supreme Court of Canada articulated 2008 CanLIIDocs 35 exactly why this kind of faultless liability exists in Canada, and how it is justifed. In medical malpractice cases involving teaching hospitals, there are usually three possible defendants to a negligence action: the attending physician, the treating resident, and the hospital. Due to the legal nature of their employment relationship, if the resident is found liable, so too is her employer, the hospital. Tis liability is regardless of fault. Te attending physician, on the other hand, can only be held liable with fault. Tis paper proposes that imposing vicarious liability on the hospital or any other party in this type of action is inconsistent with the justifcations outlined in Bazley v. Curry. Liability in this particular context, it is argued, should be limited to liability with fault. Tis paper also briefy explores possible reasons why the courts have demonstrated a general preference to have hospitals, rather than attending physicians, pay judgments to injured plaintifs. It takes notice of a newly emerging non-delegable duty of care owed by hospitals to patients, and further points out the unique public source of funding for malpractice judgments regardless of who is liable. -

Corporate Liability for Economic Crime, Call for Evidence

Corporate Liability for Economic Crime Call for evidence This Call for Evidence begins on 13 January 2017 This Call for Evidence ends on 24 March 2017 Corporate Liability for Economic Crime Call for evidence Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty January 2017 Cm 9370 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://consult.justice.gov.uk/ Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to Criminal Law & Sentencing Policy Unit at [email protected] Print ISBN 9781474139052 Web ISBN 9781474139069 ID 181116 01/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office About this call for evidence To: This call for evidence invites academics, business, civil society, lawyers and other interested parties across the UK to consider whether there is a case for changes to the regime for corporate criminal liability for economic crime in the United Kingdom. Duration: -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

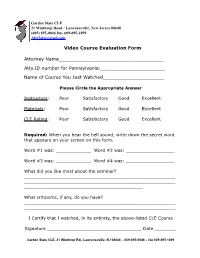

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Damien A. Macias V. Summit Management, No

Damien A. Macias v. Summit Management, No. 1130, Sept. Term, 2018 Opinion by Leahy, J. Motion for Summary Judgment > Scope of Review Maryland premises-liability law allows disposition on summary judgment when the pertinent historical facts are not in dispute. See Hansberger v. Smith, 229 Md. App. 1, 13, 21-24 (2016); see also Richardson v. Nwadiuko, 184 Md. App. 481, 483-84 (2009). Negligence > Premises Liability >Foreseeability Foreseeability—the principal consideration in actionable negligence—is not confined to the proximate cause analysis. See Kennedy Krieger Institute, Inc. v. Partlow, 460 Md. 607, 633-34 (2018); Valentine v. On Target, Inc., 112 Md. App. 679, 683-84 (1996), aff'd, 353 Md. 544 (1999). Negligence > Premises Liability >Duty The status of an entrant, and the legal duty owed thereto, are questions of law informed by the historical facts of the case. See Troxel v. Iguana Cantina, LLC, 201 Md. App. 476, 495 (2011). Negligence > Duty to Invitees > Condominium Associations Condominium unit owners and their guests occupy the legal status of invitee when they are in the common areas of the complex over which the condominium association maintains control. Barring any agreements or waivers to the contrary, the condominium association is bound to exercise “reasonable and ordinary care” to keep the premises safe for the invitee and to “protect the invitee from injury caused by an unreasonable risk which the invitee, by exercising ordinary care for his [or her] own safety, will not discover.” See Bramble v. Thompson, 264 Md. 518, 521 (1972). Negligence > Premises Liability >Legal Status An entrant’s legal status is not static and may change through the passage of time or through a change in location. -

State of Delaware Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF DELAWARE RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Updated in 2017 by Cooch and Taylor 1000 N. West St., 10th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Phone: (302) 984-3800 www.coochtaylor.com 2017 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS The Delaware State Court System ............................................................................... 2-3 Trial Courts ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 The Justice of the Peace Court .................................................................................................................. 2 The Court of Common Pleas ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Superior Court .................................................................................................................................... 2 The Family Court ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The Chancery Court ................................................................................................................................... 3 Appellate Court ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Supreme Court of the State of Delaware ........................................................................................... 3 General -

Government Responsibility for Constitutional Torts Christina B

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 1986 Government Responsibility for Constitutional Torts Christina B. Whitman University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/328 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Common Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Supreme Court of the United States Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Whitman, Christina B. "Government Responsibility for Constitutional Torts." Mich. L. Rev. 85 (1986): 225-76. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOVERNMENT RESPONSIBILITY FOR CONSTITUTIONAL TORTS Christina B. Whitman* This essay is about the language used to decide when governments should be held responsible for constitutional torts.' Debate about what is required of government officials, and what is required of government itself, is scarcely new. What is new, at least to American jurispru- dence, is litigation against government units (rather than government officials) for constitutional injuries. 2 The extension of liability to insti- tutional defendants introduces special problems for the language of responsibility. In a suit against an individual official it is easy to de- scribe the wrong as the consequence of individual behavior that is in- consistent with community norms; the language of common-law tort, which refers explicitly to those norms, has seemed to provide a useful starting point for evaluating that behavior.3 When the defendant is an institution, the language of tort provides no such ground because tra- * Professor of Law, University of Michigan.