An Analysis of US Media Coverage of Terrorism from 2011–2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S8188

S8188 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE November 30, 2015 the three holds I have on ambassa- to be with our families and give thanks Republicans to consider calling on the dorial nominations: Mr. Samuel Heins, for all of the great goodness we have floor of the Senate—in light of all of who is nominated to be the U.S. Am- had showered on us as individuals and this gun violence—commonsense re- bassador to Norway, and Ms. Azita those lucky enough to live in this great forms that would keep guns out of the Raji, who is nominated to be the U.S. Nation, but for many families this was hands of dangerous people. Ambassador to Sweden. I believe both a painful holiday weekend. It is sober- Whether or not you own a gun, are qualified to represent our Nation ing to realize how many American fam- whether or not you hunt, whatever abroad, and we have significant inter- ilies have their lives impacted by gun your view is of the Constitution, can’t ests in Scandinavia. My hope is that violence in America every single day. we all basically agree that people who both nominees receive a vote and are Sadly, the past holiday weekend was have been convicted of a felony and confirmed in the Senate sooner rather no exception. those who are mentally unstable than later. In my home State of Illinois, in the should not be allowed to buy a gun? I will retain, however, the hold on city of Chicago, gun violence has taken That, to me, is just common sense. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JANUARY 7, 2016 No. 4 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, January 11, 2016, at 2 p.m. House of Representatives THURSDAY, JANUARY 7, 2016 The House met at 10 a.m. and was ican workers who seek jobs that pay This claimed labor shortage is unsup- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- enough to support their families. ported by jobs or wage data and is po- pore (Mr. LAHOOD). In December, on less than 72 hours’ litical bunk. Per Federal labor statis- f notice, Congress and President Obama tics, 57 percent—57 percent—of Ameri- shoved down the throats of Americans cans without a high school diploma had DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO a 2,000-page, financially irresponsible, no job in 2015’s second quarter. That TEMPORE $1.1 trillion omnibus spending bill that bears repeating. Fifty-seven percent of The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- not only risks America’s solvency, it Americans without a high school di- fore the House the following commu- also threatens American jobs for Amer- ploma had no job in 2015’s second quar- nication from the Speaker: ican workers. ter. That is a lot of Americans who Under old law, 66,000 H–2B foreign WASHINGTON, DC, would love to have those jobs President January 7, 2016. worker visas could be issued each year. -

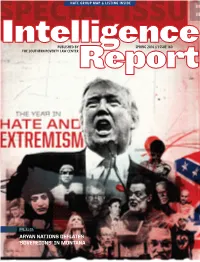

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

SUPREME COURT, STATE of COLORADO 2 East 14Th Ave., Denver, Colorado 80203 Original Proceeding Pursuant to C.A.R

SUPREME COURT, STATE OF COLORADO 2 East 14th Ave., Denver, Colorado 80203 Original Proceeding Pursuant to C.A.R. 21 DATE FILED: February 16, 2016 4:49 PM El Paso County Dist. Court, Case No. 2015CR5795 Honorable Gilbert Martinez, Chief Judge In re: People v. Robert Lewis Dear, Jr. PETITIONERS: ABC, Inc; The Associated Press; Cable News Network, Inc. (“CNN”); CBS News, a division of CBS Broadcasting Inc., and KCNC-TV, owned and operated by CBS Television Stations Inc.; Colorado Broadcasters Association; Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition; Colorado Press Association; Colorado Springs Independent; The Denver Post; Dow Jones & Company; First Look Media, Inc.; Fox News Network, LLC; Gannett Co., Inc.; The Gazette; KDVR-TV, Channel 21; KKTV-TV, Channel 11; KMGH-TV, Channel 7; KRDO-TV, Channel 13; KUSA- TV, Channel 9; KWGN-TV, Channel 2; NBCUniversal Media, LLC; The New York Times Company; The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press; Rocky Mountain PBS; The E.W. Scripps Company; TEGNA, Inc.; Tribune Media Company, and the Washington Post Company, and RESPONDENTS: District Court for the Fourth Judicial District of Colorado (the Hon. Gilbert Martinez, Chief Judge, presiding). COURT USE ONLY CYNTHIA H. COFFMAN, Attorney General FREDERICK R. YARGER, Solicitor General* GRANT T. SULLIVAN, Assistant Solicitor General* Case No.: 2016SA13 MATTHEW D. GROVE, Assistant Solicitor General* 1300 Broadway, 6th Floor Denver, CO 80203 Phone: (720) 508-6349 (Sullivan) / 6157 (Grove) Fax: (720) 508-6041 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Registration Numbers: 39479, 40151, 34269 *Counsel of Record THE HONORABLE GILBERT MARTINEZ’S ANSWER TO ORDER AND RULE TO SHOW CAUSE CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I hereby certify that this brief complies with all requirements of C.A.R. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JULY 12, 2016 No. 112 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Now, I am proud to say that this bill leaders focus on preparing students for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- passed unanimously out of committee, the workforce—not duplicative or over- pore (Mr. WEBSTER of Florida). which is good news because a reauthor- ly prescriptive Federal requirements— f ization is badly needed. and enable them to determine the best It is no secret that our country con- way to do so. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO tinues to face significant economic To increase transparency and ac- TEMPORE challenges, and it is no surprise that countability, H.R. 5587 streamlines per- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- many men and women are worried formance measures to ensure sec- fore the House the following commu- about their futures and their family’s ondary and post-secondary programs nication from the Speaker: future. Last week a Gallup poll found deliver results, helping students grad- uate, prepared to secure a good-paying WASHINGTON, DC, that 54 percent—just 54 percent—of July 12, 2016. Americans believed today’s young peo- job or further their education. The bill I hereby appoint the Honorable DANIEL ple will live a better life than their also includes measures to provide stu- WEBSTER to act as Speaker pro tempore on parents. -

2019-20 U.S. FIGURE SKATING MEDIA GUIDE Nathan Chen 2019 World Champion Vincent Zhou 2019 World Bronze Medalist TABLE of CONTENTS

2019-20 U.S. FIGURE SKATING MEDIA GUIDE Nathan Chen 2019 World champion Vincent Zhou 2019 World bronze medalist TABLE OF CONTENTS U.S. FIGURE SKATING U.S. Ladies Team .....................31 Marketing & Communications Staff ...... 2 U.S. Men’s Team ......................45 Media Credential Guidelines ............ 3 U.S. Pairs Team ......................63 Headquarters ..........................6 U.S. Ice Dance Team .................75 Figure Skating on Television ............ 7 HISTORY & RESULTS Streaming Figure Skating Online . .8 History of Figure Skating ..............88 Figure Skating by the Numbers .........9 World & U.S. Hall of Fame ............ 90 Figure Skating Record Book .......... 94 VIEWERS GUIDE TO FIGURE SKATING Olympic Winter Games ............... 102 Disciplines ............................ 10 World Championships ................108 Ladies & Men’s .........................11 World Junior Championships ......... 128 Pairs .................................12 Four Continents Championships ...... 138 Ice Dance ............................13 Grand Prix Final. .144 INTERNATIONAL JUDGING SYSTEM Junior Grand Prix Final ...............150 Overview .............................14 Skate America ....................... 156 Judges & Officials .....................15 U.S. Championships .................. 165 Program Components .................16 IJS Best Scores ...................... 185 Calculations ..........................17 U.S. Qualifying Best Scores ........... 189 Scales of Values (SOV) ................18 Skate America Best -

In Studio, Online Rates for Both Residential from His fi Nal Sermon and Commercial Properties at Hope Chapel on Actually Decreased from Nov

EVENT FOOTBALL TRINITY CHURCH SUPER BOWL FESTIVAL OF TREES SEQUEL PAGE B3 PAGE B1 Thursday, December 3, 2015 Melrose.WickedLocal.com Vol. 118, No. 28 ■ $2 MORE INSIDE NATIVE SON SCHOOLS, A2 Melrose remembers Garrett Swasey By Aaron Leibowitz save,” President Barack Obama former Olympian Nancy Ker- [email protected] said in a statement, “and may He rigan, who is from Stoneham. grant the rest of us the courage After school, David Swasey Before he was a police of cer, a to do the same thing.” would pick up Kerrigan and pastor, a champion fi gure skater Swasey was born in Melrose drive her and Garrett to the rink, and a hero, Garrett Swasey was and grew up at 24 Park St. with Kerrigan told Wicked Local’s a boy with big dreams. his parents, David and Sheila, news partner, WCVB. “Watch 96 Olympics,” Swasey and his sister, Kimberly. Every In June of 1991, Swasey left BLUE RIBBON told his classmates in the 1989 morning, Swasey would wake up Melrose for Colorado Springs Melrose High School yearbook. early to skate in Stoneham. By to train with Christine Fowler- “See you there.” the time he got to school each Binder, according to the U.S. PROFILES, A3 Swasey, 44, was one of three day, he was exhausted. Figure Skating website. On Jan. people killed last Friday, Nov. 27, “A few of our science classes 11, 1992, the pair won gold at the by a shooter at a Planned Parent- early in the day, he was always U.S. junior ice dancing champi- hood Clinic in Colorado Springs. -

Senate Has Done the Finding That Common Ground, Finding I Want to Express My Condolences to Same Hard Work

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 161 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2015 No. 175 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE backyards of Savannah and the local called to order by the Speaker. The SPEAKER. Will the gentleman bootlegger who bribed local law en- from Georgia (Mr. CARTER) come for- forcement. f ward and lead the House in the Pledge Tom’s extraordinary career as a jour- nalist and his work over the years has of Allegiance. made life better for many people. He PRAYER Mr. CARTER of Georgia led the will truly be missed. The Chaplain, the Reverend Patrick Pledge of Allegiance as follows: J. Conroy, offered the following prayer: I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the f Father of us all, thank You for giving United States of America, and to the Repub- TAX EXTENDERS us another day. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, (Mr. SCHRADER asked and was indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. In so many ways, the world is explod- given permission to address the House ing with crisis after crisis. We ask f for 1 minute.) Your blessing on the people and city of ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER Mr. SCHRADER. Mr. Speaker, I come San Bernardino, but also upon this Na- The SPEAKER. The Chair will enter- to the floor today to state my opposi- tion, which seems plagued by so many tain up to five requests for 1-minute tion to the $800 billion of unpaid tax problems of violence and resulting extenders now being discussed in Con- speeches on each side of the aisle. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 161 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2015 No. 183 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was to wear the cloth of this country’s In our encounters with each other, called to order by the Speaker. Navy. guide us with Your steadfast love that, We would ask that You would grant in these days of tumultuous seas of f Your blessing on these whom You have conflict and raging waters of uncer- called to ensure that the voices of faith tainty, Your way be known and Your PRAYER are never silenced, to provide the sanc- path revealed. It is in the strength of Rear Admiral Margaret Grun Kibben, tuary of Your presence, to serve along- Your name we pray. Chief of Chaplains for the United side the sons and daughters who faith- Amen. States Navy, Washington, D.C., offered fully serve in every clime and place to f the following prayer: preserve the ideals You have offered. Almighty God, whose way is in the THE JOURNAL sea and whose paths are in the great In our efforts to preserve liberty, re- The SPEAKER. The Chair has exam- waters, we offer our gratitude to You, mind us that the freedoms we enjoy are ined the Journal of the last day’s pro- for the pastors, rabbis, priests, and gifts of Your grace. ceedings and announces to the House imams who, over the course of 240 In our deliberations to uphold jus- his approval thereof. -

University Students Protest Institutionalized Racism on Campuses Shooter Attacks Planned Parenthood Clinic in Colorado Springs S

Page 4 • Students protest • Obama stops XL pipeline National El Gato • Friday, December 4, 2015 • Los Gatos High School • www.elgatonews.com Shooter attacks Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs by Hyuntae Byun former soldier and Iraq War veteran, and Jennifer Markovsky, a Editor-in-Chief 35-year-old mother who was married to an Army veteran. Both Stewart On Fri., Nov. 27, a 57-year-old gunman walked into a Colorado and Markovsky were parents; Stewart was a father to two girls, and Springs Planned Parenthood clinic and opened fire, killing three Markovsky was a mother to two. The last victim was Garrett Swasey, a people, wounding nine, and sparking a five-hour gunfight that ended 44-year-old member of the University of Colorado campus police force. with his surrender. The chief suspect has been identified as Robert Following the attacks, families of the victims held several vigils. Lewis Dear, who has a history of arrests and run-ins with local police. The day after the attack, a morning event at the All Souls Unitarian The victims included civilians Ke’Arre M. Stewart, a 29-year-old Universalist Church allowed attendees to mourn and reflect. Later on Saturday, an evening event commemorated Swasey’s heroism and dedication. On Sunday, friends and family of Swasey congregated at the evangelical Hope Chapel, where Swasey was a co-pastor, for a celebration of his life, including a video of him skating. POLITICAL RESPONSE: Presidential candidate Jeb Bush said the violence was unjustifiable. Though exact motives for the attack are still unclear, some wit- nesses have reported that Dear shouted “no more baby parts!” as The shooting prompted responses from several prominent pol- he commenced his attack. -

Inside Trump Country Moms on Lsd the Gop's Real Victory

JAN/FEB 2017 INSIDE TRUMP COUNTRY MOMS ON LSD THE GOP’S REAL VICTORY Anyone who wants to make America great has to grow the economy. Here’s how. “ Never one to aim low, David Smick is calling for America to reinvent herself through a new innovative era of ‘mass fl ourishing.’ And even more impressive, he’s written a game plan on how to do it. The Great Equalizer is chock full of can- ny insights and bold ideas; it defi nitely deserves a close read.” —PAUL RYAN, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives “ The next U.S. President should thank David Smick for The Great Equalizer.” —BILL BRADLEY, former U.S. Senator “ Whoever advises the next president on economics will want to read this book.” —LAWRENCE SUMMERS , former secretary of the U.S. Treasury Pataja © Tec www.publicaffairsbooks.com • Available now in hardcover and e-book wherever books are sold GreatEqualizer_ad4 Final.indd 1 11/11/16 1:03 PM contents JAN/FEB 2017 UP FRONT 6 Trump’s Vanishing Base 20 Blue-collar whites put him over the top. It won’t happen again. BY BOB MOSER 8 The Democrats’ Biggest Disaster The GOP dominates state legislatures. BY NICOLE NAREA AND ALEX SHEPHARD 10 The Disease Detectives Why is the government spying on mosquitoes? BY CYNTHIA GRABER 11 Q&A: Bad Education For-profit colleges don’t work. So how can we stop them? BY RACHEL M. COHEN 13 #IHeartMyDictator Authoritarian regimes are winning the social media wars. BY SEAN WILLIAMS COLUMNS 16 Great White Hopes Why did the rural working class elect Trump? BY ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD 18 He’s Making a List Trump is more paranoid and dangerous than Nixon. -

Obama Slams Gun Violence After Shooting French PM Calls on Gulf to Accept More... Scans Point to Hidden Chamber in Tut's Tomb

NEWS SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2015 Reps attack Muslims with impunity Continued from Page 1 quences,” Mogahed said. “We’ve really moved the threshold of what is socially acceptable.” Other inflammatory rhetoric from the Trump and Carson Singling out Muslims is not new. Before the 2012 presiden- campaigns has generated far different reactions. When Trump tial election, Republican candidate Newt Gingrich called for a announced his campaign, he said Mexican immigrants are federal ban on Islamic law and said Muslims could hold public “bringing crime. They’re rapists.” He was widely denounced. office in the US if “the person would commit in public to give Polls find Latinos strongly disapprove of his candidacy and his up sharia”. Huckabee, then considering a presidential run, remarks alienated other immigrant groups. The potency of called Islam “the antithesis of the gospel of Christ”. comments criticizing Muslims was apparent even before But candidates at the top of the field stayed away from recent attacks by extremists in France, Lebanon and Egypt. such rhetoric. “The kind of things that Donald Trump and Ben Carson’s campaign reported strong fundraising and more Carson are saying today are things that Mitt Romney would than 100,000 new Facebook friends in the 24 hours after he have never said,” said Farid Senzai, a political scientist at Santa told NBC’s “Meet the Press” in September, “I would not advo- Clara University. Romney was the Republican nominee in cate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation.” Campaign 2012. Criticism of Muslims is hardly limited to presidential manager Barry Bennett told AP, “While the leftwing is huffing campaigns.