Farr FERNWOOD AREA in 1860 One of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Impact Study Stage 1 Final – Rev 0

202 - 2780 Veterans Memorial Parkway Victoria, BC, V9B 3S6 Phone: 778-433-2672 web: www.greatpacific.ca E-Mail: [email protected] COWICHAN VALLEY REGIONAL DISTRICT MARINE DISCHARGE OUTFALL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STUDY STAGE 1 FINAL – REV 0 Attention: Cowichan Valley Regional District 175 Ingram Street Duncan, BC V9L 1N8 June 25, 2015 1019-001 REV 0 Cowichan Valley Regional District Marine Discharge Outfall - EIS Executive Summary The Cowichan Valley Regional District (CVRD) is undertaking the development of Amendment 3 to the existing Central Sector Liquid Waste Management Plan (CSLWMP). The Central Sector is serviced by the Joint Utilities Board (JUB) Lagoon Systems co-owned by the City of Duncan and the Municipality of North Cowichan, and also provides service to properties within parts of CVRD Electoral Areas D and E and parts of Cowichan Tribes reserve. The Joint Utilities Board (JUB) sewage treatment lagoons are located adjacent to the Cowichan River. The aerated lagoon treatment system produces secondary quality effluent, which is disinfected by chlorination, then dechlorinated. Treated wastewater is discharged into the lower reaches of the Cowichan River and subsequently to the Cowichan Estuary and ocean environment. In recent years, low flows in the Cowichan River have resulted in a situation where there is insufficient dilution of the effluent plume with respect to the river flow. This resulted in the temporary closure of the Cowichan River to recreational activities in August of 2014. It is proposed that the point of discharge be moved from the Cowichan River to the marine environment of Satellite Channel, where significantly more dilution can be achieved and where the likelihood of interaction between the effluent plume and sensitive areas can be reduced. -

A Study of the Wellington Miners5 Strike of 1890-911 JEREMY MOUAT

The Politics of Goal: A Study of the Wellington Miners5 Strike of 1890-911 JEREMY MOUAT The coal miners of Vancouver Island occupy a special place in the history of British Columbia. The communities in which they and their families lived — Ladysmith, Wellington, Nanaimo, and Cumberland — experi enced class tensions to a degree and duration rarely seen in other parts of the province. An Island miner involved in the 1912 strike, for example, might have had a grandparent who went through the 1877 strike or a parent who witnessed the 1890 strike. These outbursts of militancy reflect the uneasiness in the social relations of production on the coal fields. Class tensions found expression in other ways as well, such as the ethnic preju dice of the miners or their left-leaning political representatives. Each strike was fought out in a different context, informed both by past struggles and current conditions. What follows is an attempt to explore the context of one such episode, the Wellington strike of 1890-91. It began quietly enough on a Monday morning, 19 May 1890, when miners employed at the Dunsmuirs' Wellington colliery on Vancouver Island arrived late for work. The action expressed their demand for an eight-hour working day and recognition of their union. The Dunsmuirs refused to grant either of these, and an eighteen-month struggle followed. When the strike was finally called off in November 1891, the Wellington miners had failed to achieve their two goals. The strike has received scant attention from historians, a neglect it scarcely deserves.2 At a time when the industry played a vital role in the 1 I would like to thank R. -

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Pete Davidson∗, Robert W Butler∗+, Andrew Couturier∗, Sandra Marquez∗ & Denis LePage∗ Final report to Parks Canada by ∗Bird Studies Canada and the +Pacific WildLife Foundation December 2010 Recommended citation: Davidson, P., R.W. Butler, A. Couturier, S. Marquez and D. Lepage. 2010. Status and Distribution of Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Bird Studies Canada & Pacific Wildlife Foundation unpublished report to Parks Canada. The data from this survey are publicly available for download at www.naturecounts.ca Bird Studies Canada British Columbia Program, Pacific Wildlife Research Centre, 5421 Robertson Road, Delta British Columbia, V4K 3N2. Canada. www.birdscanada.org Pacific Wildlife Foundation, Reed Point Marine Education Centre, Reed Point Marina, 850 Barnet Highway, Port Moody, British Columbia, V3H 1V6. Canada. www.pwlf.org Contents Executive Summary…………………..……………………………………………………………………………………………1 1. Introduction 1.1 Background and Context……………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Previous Studies…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 2. Study Area and Methods 2.1 Study Area……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 2.2 Transect route……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3 Kernel and Cluster Mapping Techniques……………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3.1 Kernel Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.3.2 Clustering Analysis………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.4 -

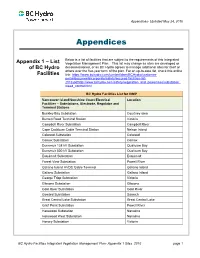

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016 Appendices Below is a list of facilities that are subject to the requirements of this Integrated Appendix 1 – List Vegetation Management Plan. This list may change as sites are developed or of BC Hydro decommissioned, or as BC Hydro agrees to manage additional sites for itself or others over the five-year term of the plan. For an up-to-date list, check this online Facilities link: https://www.bchydro.com/content/dam/BCHydro/customer- portal/documents/corporate/safety/secured-facilities-list- 2013.pdfhttp://www.bchydro.com/safety/vegetation_and_powerlines/substation_ weed_control.html. BC Hydro Facilities List for IVMP Vancouver Island/Sunshine Coast Electrical Location Facilities – Substations, Electrode, Regulator and Terminal Stations Buckley Bay Substation Courtney area Burnett Road Terminal Station Victoria Campbell River Substation Campbell River Cape Cockburn Cable Terminal Station Nelson Island Colwood Substation Colwood Comox Substation Comox Dunsmuir 138 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Dunsmuir 500 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Esquimalt Substation Esquimalt Forest View Substation Powell River Galiano Island HVDC Cable Terminal Galiano Island Galiano Substation Galiano Island George Tripp Substation Victoria Gibsons Substation Gibsons Gold River Substation Gold River Goward Substation Saanich Great Central Lake Substation Great Central Lake Grief Point Substation Powell River Harewood Substation Nanaimo Harewood West Substation Nanaimo Horsey Substation Victoria BC Hydro Facilities Integrated Vegetation -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Winter 2004 Volume 18

CON TROVERSY LOOKOUT #18 • a forum for writers 3516 W. 13th Ave., Vancouver, BC V6R 2S3 LOOKOUTLOOKOUTLOOKOUT s Richard Heinberg recounts in Power A Down: Options and Actions for a Post- Petroleum is Carbon World (New Society $22.95), America was the world’s foremost oil producer during the period when mankind evolved from ox carts to jet planes. For much of that century, USSR production of oil ranked second. $ According to Heinberg, oil discovery in America peaked in the 1930s; its oil pro- water. You notice now that the raft is surrounded by many sound-looking canoes, each duction peaked around 1970; but by then America hadP established its linksO with the carrying aWER family of indigenous fishers. Men on the raft are systematically forcing peo- Middle East for oil imports. Soviet oil production peaked in 1987. During the Eight- ple out of the canoes and onto the raft at gunpoint, and shooting holes in the bottoms ies, the CIA fomented proxy wars in Soviet territories (i.e. Osama bin Laden in Af- of the canoes. This is clearly insane behaviour: the canoes are the only possible sources ghanistan) and Saudi Arabia was persuaded to flood the world oil market with cheap of escape or rescue if the raft goes down, and taking more people on board the already oil. The Soviet Union crumbled. overcrowded raft is gradually bringing its deck even with the water line. You reckon The lone superpower left standing was determined to keep it that way. “If, instead that there must now be four hundred souls aboard. -

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: a Canadian War Story

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: A Canadian War Story Bruce Davies Curator © Craigdarroch Castle 2016 2 Abstract As one of many military hospitals operated by the federal government during and after The Great War of 1914-1918, the Dunsmuir house “Craigdarroch” is today a lens through which museum staff and visitors can learn how Canada cared for its injured and disabled veterans. Broad examination of military and civilian medical services overseas, across Canada, and in particular, at Craigdarroch, shows that the Castle and the Dunsmuir family played a significant role in a crucial period of Canada’s history. This paper describes the medical care that wounded and sick Canadian soldiers encountered in France, Belgium, Britain, and Canada. It explains some of the measures taken to help permanently disabled veterans successfully return to civilian life. Also covered are the comprehensive building renovations made to Craigdarroch, the hospital's official opening by HRH The Prince of Wales, and the question of why the hospital operated so briefly. By highlighting the wartime experiences of one Craigdarroch nurse and one Craigdarroch patient, it is seen that opportunities abound for rich story- telling in a new gallery now being planned for the museum. The paper includes an appendix offering a synopsis of the Dunsmuir family’s contributions to the War. 3 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................. 04 I. Canadian Medical Services -

Jun17-1915.Pdf (8.204Mb)

•'V Vol. XV., 15th Ye»r, No, 24. DUNCAN, B. C., THDEsilAY, JUNE l?th, 1915. Subscription |1 Yearly hi Advance North Cowichan Cattle Question At the Front Casual^ List The Fortune of War Batepayers Pass Two Eesolutions—Matter flow Coiriehan Boys More Cowiclian Men To Be Decided By Plebiscite Behave Under Fire Among Wonnded The Leader is' indebted \ Last Thursday 'morning ’s list show The eatUe on roads question roads The point was that the nation J. H. Gillespie. DAA. and Q.M.C. ed that Cowiehan boys had been in shelved by North Cowiehan conneil was at war and they wanted to raise central camp, Vei the thick of the fighting. In addition on Monday at a qiecial meeting of I they could, as there B. Cw for the following letter written which no i^tifieation had been given would be. a meat ahorse all over Lance-Corporal J. C Ciceri, Lance 10 him by Sergeant Cleland, 7th Bat- to the pres? or the public. • * the world. She said that many had talion. in whose pbloon most of the Corporal Dennis Ashby and Private From the resolutions it is learned put all their available land ouder cul- Cowiehan men are (o be found. Dated J. L. A. -Gibbs, noted laR week as that Councilors Herd and Pahner trvation. ' from France, May 21st. he writes: ' wounded, and Private H. C. Bridges sponsored a luotion *that the pound Major Mntter said that if people "My dear Cspt. Gillespie:—This is bylaw be neither amended nor raid not feed their stock they had suffering from shock, the list of just a short letter to lell yon how pealed until the reanlt of the plebis > right W keep them. -

The Influence of Political Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1977 The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia Henrik J. von Winthus Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation von Winthus, Henrik J., "The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia" (1977). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1432. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1432 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL LEADERS ON THE PROVINCIAL PERFORMANCE OF THE LIBERAL PARTY IN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Henrik J. von Winthus ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development of Liberalism In British Columbia from the aspect of leader influence. It intends to verify the hypothesis that in the formative period of provincial politics in British Columbia (1871-1941) the average voter was more leader- oriented than party-oriented. The method of inquiry is predominantly historical. In chronological sequence the body of the thesis describes British Columbia's political history from 1871, when the province entered Canadian confederation, to the resignation of premier Thomas Dufferin Pattullo, in 1941. The incision was made at this point, because the following eleven year coalition period would not yield data relevant to the hypothesis. Implicitly, the performance of political leaders has also been evaluated in the light of Aristotelian expectations of the 'zoon politikon'. -

Crofton, BC, Canada | Red Seal Recruiting

Crofton, BC http://www.croftonbc.com/ The active community of Crofton is situated on the calm waters of Osborne Bay in the Cowichan Valley, 22 minutes’ drive from Duncan. It is home to 2,500 people. The modern town of Crofton was founded in 1902 by Henry Croft, who owned a nearby copper in Mt. Sicker. He used the town to build a smelter, export his copper, and house his workers. The town prospered until world copper prices dropped, causing the closure of the mine in 1908. The miners struggled to find work in the logging and fishing industries until 1956, when a large pulp and paper mill was built on the outskirts of town, attracted by Crofton's deep-sea port. The mill is still in operation today. These days, this friendly forestry community offers quiet parks, comfortable accommodation and a host of family activities such as golfing, swimming, fishing, hiking, and wildlife viewing. Close to Victoria and Nanaimo, Crofton is also is home to one of the ferries heading to Saltspring Island. Phone: 1-855-733-7325 Email: [email protected] Weather Crofton has mild temperatures and above average rainfall. Average Yearly Precipitation Average Days with Rainfall per Year: 141.5 Average Days with Snowfall per Year: 9.8 Seasonal Average Temperatures (˚C) January: 2.7˚ April: 8.8˚ July: 17.9˚ October: 9.7˚ Additional Information For further information about annual climate data for Port Alberni, please use the following links to visit The Weather Network or Environment Canada http://www.theweathernetwork.com/ http://www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/canada_e.ht ml. -

Japanese Immigration to British Columbia and the Vancouver Riot of 1907

Japanese Immigration to British Columbia and the Vancouver Riot of 1907 ––––––– A Sourcebook Selected, transcribed and annotated By Chris Willmore Cover: Anonymous. (c. 1912). Japanese Women, Vancouver [Photograph]. Collection of C. Willmore Victoria, B.C. November 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. 2 Table of Contents Antecedents ..................................................................................................................................5 “A great kindness toward Japan” (October 5, 1893) ............................................................................................ 5 “Regularly as clock work” (March 13, 1895) ........................................................................................................ 5 “Scarce this year” (August 12, 1895) .................................................................................................................... 6 “It was not Japan’s desire” (January 25, 1896) .................................................................................................... 6 “Perfect and efficient laws” (July 6, 1896) ........................................................................................................... 7 “Not conducive to the general good” (March 7, 1901) ...................................................................................... 10 “The Japanese question” (August 7, 1907) ....................................................................................................... -

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series Legislative Assembly of British Columbia Victoria British Columbia V8V 1X4 CONTENTS UP TO 1858 1 1843 – Fort Victoria is Established 1 1846 – 49th Parallel Becomes International Boundary 1 1849 – Vancouver Island Becomes a Colony 1 1850 – First Aboriginal Land Treaties Signed 2 1856 – First House of Assembly Elected 2 1858 – Crown Colony of B.C. on the Mainland is Created 3 1859-1870 3 1859 – Construction of “Birdcages” Started 3 1863 – Mainland’s First Legislative Council Appointed 4 1866 – Island and Mainland Colonies United 4 1867 – Dominion of Canada Created, July 1 5 1868 – Victoria Named Capital City 5 1871-1899 6 1871 – B.C. Joins Confederation 6 1871 – First Legislative Assembly Elected 6 1872 – First Public School System Established 7 1874 – Aboriginals and Chinese Excluded from the Vote 7 1876 – Property Qualification for Voting Dropped 7 1886 – First Transcontinental Train Arrives in Vancouver 8 1888 – B.C.’s First Health Act Legislated 8 1893 – Construction of Parliament Buildings started 8 1895 – Japanese Are Disenfranchised 8 1897 – New Parliament Buildings Completed 9 1898 – A Period of Political Instability 9 1900-1917 10 1903 – First B.C Provincial Election Involving Political Parties 10 1914 – The Great War Begins in Europe 10 1915 – Parliament Building Additions Completed 10 1917 – Women Win the Right to Vote 11 1917 – Prohibition Begins by Referendum 11 CONTENTS (cont'd) 1918-1945 12 1918 – Mary Ellen Smith, B.C.’s First Woman MLA 12 1921 – B.C. Government Liquor Stores Open 12 1920 – B.C.’s First Social Assistance Legislation Passed 12 1923 – Federal Government Prohibits Chinese Immigration 13 1929 – Stock Market Crash Causes Great Depression 13 1934 – Special Powers Act Imposed 13 1934 – First Minimum Wage Enacted 14 1938 – Unemployment Leads to Unrest 14 1939 – World War II Declared, Great Depression Ends 15 1941 – B.C.