Italian Champion Struggles to Compete Globally Case Taken from the International Business Environment, Second Edition (Palgrave, 2006), by Janet Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

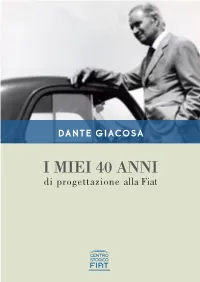

I MIEI 40 ANNI Di Progettazione Alla Fiat I Miei 40 Anni Di Progettazione Alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA

DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat Editing e apparati a cura di: Angelo Tito Anselmi Progettazione grafica e impaginazione: Fregi e Majuscole, Torino Due precedenti edizioni di questo volume, I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat e Progetti alla Fiat prima del computer, sono state pubblicate da Automobilia rispettivamente nel 1979 e nel 1988. Per volere della signora Mariella Zanon di Valgiurata, figlia di Dante Giacosa, questa pubblicazione ricalca fedelmente la prima edizione del 1979, anche per quanto riguarda le biografie dei protagonisti di questa storia (in cui l’unico aggiornamento è quello fornito tra parentesi quadre con la data della scomparsa laddove avve- nuta dopo il 1979). © Mariella Giacosa Zanon di Valgiurata, 1979 Ristampato nell’anno 2014 a cura di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. Logo di prima copertina: courtesy di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. … ”Noi siamo ciò di cui ci inebriamo” dice Jerry Rubin in Do it! “In ogni caso nulla ci fa più felici che parlare di noi stessi, in bene o in male. La nostra esperienza, la nostra memoria è divenuta fonte di estasi. Ed eccomi qua, io pure” Saul Bellow, Gerusalemme andata e ritorno Desidero esprimere la mia gratitudine alle persone che mi hanno incoraggiato a scrivere questo libro della mia vita di lavoro e a quelle che con il loro aiuto ne hanno reso possibile la pubblicazione. Per la sua previdente iniziativa di prender nota di incontri e fatti significativi e conservare documenti, Wanda Vigliano Mundula che mi fu vicina come segretaria dal 1946 al 1975. -

30 06 2019 Annual Financial Report

30 06 2019 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 30 06 2019 REGISTERED OFFICE Via Druento 175, 10151 Turin Contact Center 899.999.897 Fax +39 011 51 19 214 SHARE CAPITAL FULLY PAID € 8,182,133.28 REGISTERED IN THE COMPANIES REGISTER Under no. 00470470014 - REA no. 394963 CONTENTS REPORT ON OPERATIONS 6 Board of Directors, Board of Statutory Auditors and Independent Auditors 9 Company Profile 10 Corporate Governance Report and Remuneration Report 17 Main risks and uncertainties to which Juventus is exposed 18 Significant events in the 2018/2019 financial year 22 Review of results for the 2018/2019 financial year 25 Significant events after 30 June 2019 30 Business outlook 32 Human resources and organisation 33 Responsible and sustainable approach: sustainability report 35 Other information 36 Proposal to approve the financial statements and cover losses for the year 37 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 30 JUNE 2019 38 Statement of financial position 40 Income statement 43 Statement of comprehensive income 43 Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 44 Statement of cash flows 45 Notes to the financial statements 48 ATTESTATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 154-BIS OF LEGISLATIVE DECREE 58/98 103 BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT 106 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 118 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT AT 30 06 19 5 REPORT ON OPERATIONS BOARD OF DIRECTORS, BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIRMAN Andrea Agnelli VICE CHAIRMAN Pavel Nedved NON INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS Maurizio Arrivabene Francesco Roncaglio Enrico Vellano INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS Paolo Garimberti Assia Grazioli Venier Caitlin Mary Hughes Daniela Marilungo REMUNERATION AND APPOINTMENTS COMMITTEE Paolo Garimberti (Chairman), Assia Grazioli Venier e Caitlin Mary Hughes CONTROL AND RISK COMMITTEE Daniela Marilungo (Chairman), Paolo Garimberti e Caitlin Mary Hughes BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS CHAIRMAN Paolo Piccatti AUDITORS Silvia Lirici Nicoletta Paracchini DEPUTY AUDITORS Roberto Petrignani Lorenzo Jona Celesia INDEPENDENT AUDITORS EY S.p.A. -

Cento Anni AL SERVIZIO DEL CALCIO a TUTELA DELLE REGOLE

n. 1/2011 Rivista fondata nel 1924 da G. Mauro e O. Barassi CENTO ANNI AL SERVIZIO DEL CALCIO A TUTELA DELLE REGOLE AssociAzione itAliAnA Arbitri Pubblicazione periodica Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Roma499 del 01/09/89 - Posta Italiane s.p.a. - Sped. in abb. post. - Art. D.L. 353/2003 - (Conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n°46) art. 1, comma 2, DCB Roma di Roma499 del 01/09/89 - Posta Italiane s.p.a. Sped. in abb. post. Art. D.L. 353/2003 (Conv. Pubblicazione periodica Autorizzazione del Tribunale Umberto Meazza, Anno LXIX n. 1/2011 nella foto a destra, primo Presidente dell’Associazione Italiana Arbitri, con Renzo De Vecchi storico capitano azzurro Direttore Marcello Nicchi Direttore Responsabile Mario Pennacchia Comitato di Redazione Narciso Pisacreta, Alfredo Trentalange, Filippo Antonio Capellupo, Umberto Carbonari, Massimo Della Siega, Maurizio Gialluisi, Erio Iori, Giancarlo Perinello, Francesco Meloni Coordinatori Carmelo Lentino Alessandro Paone Salvatore Consoli Referenti Abruzzo Marco Di Filippo Basilicata Francesco Alagia Calabria Paolo Vilardi Campania Giovanni Aruta Emilia Romagna Vincenzo Algeri Friuli Venezia Giulia Massimiliano Andreetta Lazio Teodoro Iacopino Liguria Federico Marchi Lombardia Paolo Cazzaniga Marche Emanuele Frontoni Molise Andrea Nasillo Piemonte Valle d’Aosta Davide Saglietti Puglia Corrado Germinario Sardegna Valentina Chirico Sicilia Rodolfo Puglisi Toscana Francesco Querusti Trentino Alto Adige Adriano Collenz Umbria Alessandro Apruzzese Veneto Samuel Vergro Segreteria di Redazione Gennaro Fiorentino Direzione-redazione Via Tevere 9 - 00198 ROMA Tel. 06 84915026 / 5041 - Fax 06 84915039 Sito internet: www.aia-figc.it e-mail: [email protected] Realizzazione grafica e stampa Grafiche Marchesini s.r.l. Via Lungo Bussè, 884 - Angiari/Verona wwww.grafichemarchesini.it [email protected] Pubblicazione periodica Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Roma n. -

30 06 2019 Annual Financial Report

30 06 2019 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 30 06 2019 WorldReginfo - 5e6c0907-48a0-45c0-a606-45719a985900 WorldReginfo - 5e6c0907-48a0-45c0-a606-45719a985900 REGISTERED OFFICE Via Druento 175, 10151 Turin Contact Center 899.999.897 Fax +39 011 51 19 214 SHARE CAPITAL FULLY PAID € 8,182,133.28 REGISTERED IN THE COMPANIES REGISTER Under no. 00470470014 - REA no. 394963 WorldReginfo - 5e6c0907-48a0-45c0-a606-45719a985900 WorldReginfo - 5e6c0907-48a0-45c0-a606-45719a985900 CONTENTS REPORT ON OPERATIONS 6 Board of Directors, Board of Statutory Auditors and Independent Auditors 9 Company Profile 10 Corporate Governance Report and Remuneration Report 17 Main risks and uncertainties to which Juventus is exposed 18 Significant events in the 2018/2019 financial year 22 Review of results for the 2018/2019 financial year 25 Significant events after 30 June 2019 30 Business outlook 32 Human resources and organisation 33 Responsible and sustainable approach: sustainability report 35 Other information 36 Proposal to approve the financial statements and cover losses for the year 37 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 30 JUNE 2019 38 Statement of financial position 40 Income statement 43 Statement of comprehensive income 43 Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 44 Statement of cash flows 45 Notes to the financial statements 48 ATTESTATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 154-BIS OF LEGISLATIVE DECREE 58/98 103 BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT 106 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 118 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT AT 30 06 19 5 WorldReginfo - 5e6c0907-48a0-45c0-a606-45719a985900 -

Roma, 10 Febbraio 2016

Il 22 febbraio a Firenze la premiazione della ‘Hall of fame del calcio italiano’ Roma, 10 Febbraio 2016 - Sarà ancora una volta la splendida cornice del Salone dei Cinquecento di Palazzo Vecchio a Firenze ad ospitare lunedì 22 febbraio alle ore 11.30 la cerimonia di premiazione della ‘Hall of fame del calcio italiano’, il riconoscimento istituito nel 2011 dalla FIGC e dalla Fondazione Museo del Calcio che vedrà altri 10 fuoriclasse entrare a far parte di un firmamento calcistico dove brillano 47 stelle: Gianluca Vialli (Giocatore italiano), Ronaldo (Giocatore straniero), Roberto Mancini (Allenatore italiano), Corrado Ferlaino (Dirigente italiano), Roberto Rosetti (Arbitro italiano), Marco Tardelli (Veterano Italiano), Patrizia Panico (Calciatrice italiana), Giacinto Facchetti, Helenio Herrera, Umberto Agnelli (Premi alla memoria). Prima della cerimonia di premiazione, all’interno della Sala d’Arme di Palazzo Vecchio, 100 bambini e ragazzi delle scuole fiorentine avranno la possibilità di conoscere Ronaldo Luís Nazário de Lima, Patrizia Panico e Roberto Rosetti. L’incontro vedrà la partecipazione del Sindaco di Firenze Dario Nardella, da tempo impegnato con gli istituti scolastici del Comune in un percorso di confronto aperto con le giovani generazioni su diversi temi. La giornata proseguirà al Salone dei Cinquecento, dove saranno esposte anche le quattro Coppe del Mondo vinte dalla Nazionale che dal 19 febbraio potranno essere ammirate a Palazzo Vecchio. La miglior cornice possibile per celebrare dieci grandi protagonisti del nostro calcio, -

Juventus Football Club: from a Soccer to an Entertainment Company

LUISS TEACHING CASES Juventus Football Club: From a Soccer to an Entertainment Company Alessandro Zattoni Luiss University Rumen Pozharliev Luiss University TEACHING CASES 2020 ISBN 978-88-6105-575-9 Introduction The season 2018/19 finishes with a bittersweet flavor. The 20th of April Juventus wins – for the 35th time1 and for the 8th straight - the Italian premier league (Serie A). As the team has knocked out of both the Champions league in the quarterfinals by Ajax and the Italian cup in the eight-fi- nals by Atalanta, it is time for Juventus’ president Andrea Agnelli and the top managers to think about the future. After few weeks of doubts and rumors, the 17th of May Juventus announces that Massimiliano Allegri will not be the coach of the team in the next season. The day after Juventus organizes a highly emotional press meeting with the president and the coach to communicate the decision. After one month, the 16th of June Juventus announces that the new trainer will be Maurizio Sarri, previously coach of Napoli (2015-18) and of Chelsea (2018/19). The new coach – that won the last European League with Chelsea - has a 3-years contract and the ambition to lead the club to new victories. During the Summer, Juventus buys and sells several players, with a net loss of about €90 million (=-181,7+92). Among the new players there are talents like Matthijs de Ligt, Adrien Rabiot, Aaron Ramsey and Danilo. At the same time, some promising players like Cancelo, Kean and Spinazzola leave the team. Juventus’ objective is to continue to win and to launch another assault to the Champions League, but also to further develop the business model and to increase its brand awareness over the world. -

Kissinger Watch Bym.T

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 12, Number 7, February 19, 1985 Kissinger Watch byM.T. Upharsin 'Of Turin and in taking over Italy's Mediobanca in ulate that on that evening, Henry had one of his famous fits against Lyndon the Bohemian Grove terests from a set of interests associ ated with a director of Assicurazioni LaRouche, EIR's founder and former During the weekend of Feb. 2-4, Hen Generali di Venezia, Cesare Merza independent presidential candidate. ry A. Kissinger suddenly showed up gora. Merzagora tends to be associ That was Election Eve, and LaRouche in Turin, Italy, for meetings with the ated with certain more "conservative" was informing the American popula bigs hots of the Fiat financial empire, financial factions in Venice who are tion that Kissinger had brought "the Gianni and Umberto Agnelli and Ces somewhat more hesitant to make morality of a Bulgarian pederast" into are Romiti, whose multinationals are global "New Yalta" deals with Mos the State Department. AgneUi, tied controlled by the old Venetian and cow of the sort that Kissinger is as into high-level Balkan interests, would Swiss titled nobility. signed to negotiate. have a special appreciation for that Evidently, something of great im The Mediobanca takeover is also comment. portance was afoot. After all, the last key to attempts by the Visentini crowd Soon after, word began circulat time Henry Kissinger tried to get into to decapitate what is left of the Italian ing that Kissinger was looking for a Italy, ca. Dec. Il-12, 1984, a trip to public sector in favor of Italy's drug new way to "get" LaRouche. -

30 06 2018 Annual Financial Report

30 06 2018 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 30 06 2018 WorldReginfo - 89f1192a-3a47-426a-870a-ab2706eb9dc2 WorldReginfo - 89f1192a-3a47-426a-870a-ab2706eb9dc2 REGISTERED OFFICE Via Druento 175, 10151 Turin Contact Center 899.999.897 Fax +39 011 51 19 214 SHARE CAPITAL FULLY PAID € 8,182,133.28 REGISTERED IN THE COMPANIES REGISTER Under no. 00470470014 - REA no. 394963 WorldReginfo - 89f1192a-3a47-426a-870a-ab2706eb9dc2 WorldReginfo - 89f1192a-3a47-426a-870a-ab2706eb9dc2 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 6 REPORT ON OPERATIONS 10 Board of Directors, Board of Statutory Auditors and Independent Auditors 13 Company Profile 14 Corporate Governance Report and Remuneration Report 21 Main risks and uncertainties to which Juventus is exposed 22 Significant events in the financial year 2017/2018 26 Review of results for the financial year 2017/2018 28 Significant events after 30 June 2018 33 Business outlook 35 Human resources and organisation 36 Other information 38 Proposal for the approval of the financial statements and of cover of losses for the year 39 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 30 JUNE 2018 40 Statement of financial position 42 Income statement 45 Statement of comprehensive income 45 Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 46 Statement of cash flows 47 Notes to the financial statements 50 CERTIFICATION PURSUANT TO SECTION 154-BIS OF ITALIAN LEGISLATIVE DECREE 58/98 101 BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT 102 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 111 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT AT 30 06 18 5 WorldReginfo - 89f1192a-3a47-426a-870a-ab2706eb9dc2 -

Hall of Fame Del Calcio Italiano’: Pirlo, Boniek E Mazzone Tra I Premiati Della 9A Edizione

INIZIATIVE ‘Hall of Fame del calcio italiano’: Pirlo, Boniek e Mazzone tra i premiati della 9a edizione Nella ‘Hall of Fame’ anche Percassi, Oriali, Gama e l’ex arbitro Michelotti. Premi alla memoria per Anastasi e Radice, il premio Astori a Lukaku e a un giovane calciatore che ha salvato la vita ad un avversario. Il 4 maggio a Firenze la cerimonia di premiazione Altre 11 stelle entrano nel firmamento della ‘Hall of Fame del calcio italiano’, istituita nel 2011 dalla FIGC e dalla Fondazione Museo del Calcio per celebrare giocatori, allenatori, arbitri e dirigenti capaci di lasciare un segno indelebile nella storia del nostro calcio. Questi i premiati della 9ª edizione, che vanno a comporre una ‘rosa’ di 99 personaggi illustri formata anche da grandi campioni del passato ormai scomparsi: Andrea Pirlo (Giocatore italiano), Zbigniew Boniek (Giocatore straniero), Carlo Mazzone (Allenatore), Antonio Percassi (Dirigente italiano), Alberto Michelotti (Arbitro italiano), Gabriele Oriali (Veterano italiano), Sara Gama (Calciatrice italiana), Pietro Anastasi e Luigi Radice (Premi alla memoria), Romelu Lukaku e Mattia Agnese (Premio Astori). La Hall of Fame dà quindi il benvenuto alla classe cristallina di un Campione del Mondo come Andrea Pirlo, a Zibì Boniek, ieri ‘Bello di notte’ e oggi presidente della Federcalcio polacca e a Carlo Mazzone, uno degli allenatori italiani dotati di maggior carisma. Altri riconoscimenti sono stati assegnati ad Antonio Percassi, capace di portare la sua Atalanta nel gotha del calcio europeo, all’ex arbitro Alberto Michelotti e a Sara Gama, la capitana della Nazionale Femminile che al Mondiale francese ha tenuto incollati davanti alla Tv milioni di italiani. -

Juventus Official Fan Club Toronto

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE JUVENTUS CLUB DOC TORONTO SPRING 2011 Noi perenni testimoni di una storia senza fine… Juventus: RESULTS Serie A / Cups Guardando Who made avanti it to the end Juve Club: All the events planned for our members juventusclubdoctoronto.com 2 zeb 2.4 2.4 SPRING 2011 OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE JUVENTUS CLUB DOC TORONTO Table of Contents 2 Notes from the Editors 3 News and Notes What’s been happening in our Club 4 Juventus Club DOC Toronto Merchandise also: Comments You can contact us by e-mail at 5 The President’s Address [email protected] 6 In Memoriam Honoring members who have or by phone at (905) 856-0929 passed 7 Posta per la Squadra 8 Upcoming Club Events Wine-Tasting Event, Annual Picnic 10 Membership Perks 11 Juventus Club DOC Toronto Scholarship Program 12 Serie A 2010-2011 Risultati, classifica e la partita focale: Roma vs Juventus 13 L’Opinione di….Alfredo Olivieri 14 Our Club Events Texas Hold’em Poker Tournament 16 Promote My Juve Club 17 Around the World News from the world of soccer 18 Picture Perfect 19 Games Page World Cup Adventures Crossword 20 I risultati delle Coppe Champions League, Europa Cup, Coppa Italia, Qualificazioni Europei 22 Dove Sono Adesso? Alessio Tacchinardi 23 Juve Life Juventus Legends vs Torino Legends 24 Top 10 Libri bianconeri 25 Curiosità also: On the Net Juve-inspired links 26 Kids Play 27 Juve Kids The next generation 28 Giving Back to Our Community Agropoli Tournament 30 Wall of Fame 31 Essentials Info all members should know 32 Say What? Verbal slip-ups of our athletes Tiziana Pace Julia Pace Co-Editor in Chief Co-Editor in Chief Principal Writer Style Director Copy Writer In the past few years there has been a steady flow In the past few years, Salt Lake City has become a of foreign soccer teams into Canada in general, and soccer town. -

Lajuvelloraaumbertoagnelli

34 FÚTBOL INTERNACIONAL MUNDO DEPORTIVO Sábado 29 de mayo de 2004 El laureado técnico italiano dirigirá las próximas tres campañas al equipo 'bianconero', donde como jugador permaneció de 1970 hasta 1976 Capello deja la Roma y se fuga con la 'vecchia signora' Jordi Archs BARCELONA cera en el 'calcio', arranca así su EL GRAN BAILE DE BANQUILLOS Pierpaolo Marchetti ROMA reconstrucción en una campaña en la que deberá afrontar la fase ITALIA abio Capello, hasta ahora previa de la Liga de Campeones. EQUIPO LLEGA SE VA Juventus Fabio Capello Marcello Lippi Ftécnico de la Roma, será el Capello, que el próximo 18 de Chievo ¿ ? ¿Del Neri al Oporto? nuevo entrenador de la Ju- junio cumplirá 58 años, firmó su ventus de Turín para las tres nuevo contrato con la Juve el jue- ESPAÑA R. Madrid J. A. Camacho Carlos Queiroz próximas temporadas, según in- ves por la noche y el club turinés Atlético César Ferrando G. Manzano formó ayer el club turinés. El no ha facilitado la cifra que perci- Real Sociedad ¿ ? ¿Raynald Denoueix? anuncio se produjo pocas horas birá, aunque los medios italianos Betis ¿ ? Víctor Fernández después del fallecimiento de Um- apuntan que perderá dinero res- Málaga ¿ ? Juande Ramos Villarreal Manuel Pellegrini Paquito berto Agnelli, presidente honorífi- pecto a su etapa en la Roma. Albacete ¿José González? César Ferrando co de la Juve. Capello toma así el Celta ¿F. Vázquez? Carnero-Sáez relevo en el banquillo turinés de Ya fue jugador juventino Marcello Lippi, que se decantó por Curiosamente, Fabio Capello vuel- ALEMANIA renunciar al cargo tras una tempo- ve a una casa que conoce bien, Bayern Felix Magath Ottmar Hitzfeld rada en la que la 'vecchia signora' porque fue jugador juventino en- Stuttgart ¿ ? Felix Magath vivió una sequía total de títulos. -

Tigullio Itineraries

IV TIGULLIO ITINERARIES When all France (after the war) was teething and tittering, and busy, oh BUSY , there was ONE temple of QUIET . There was one refuge of the eternal calm that is no longer in the Christian religion. There was one place where you could take your mind and have it sluiced clean, like you can get in the Gulf of Tigullio on a June day on a bathing raft with the sun on the lantern sails. EP on Brancusi’s studio (“Brancusi” 307) Desmond Chute, Portrait of Ezra Pound, Rapallo 1929. 24 TIGULLIO ITINERARIES : EZRA POUND AND FRIENDS Massimo Bacigalupo Rapallo in Brief Tigullio is the name of the gulf at the center of which is Rapallo, limited by Portofino to the south-west and Sestri Levante to the east. Ezra Pound mentions the Tigullio with affection several times in The Cantos , recalling for example a comment by W. B. Yeats during one of their walks: “Sligo in heaven” murmured uncle William when the mist finally settled down on Tigullio. (77/493) The implication is that Yeats, being a man of Irish mists by birth and inclination, was most enthusiastic about the Tigullio when he got to see it on a misty day. On the other hand, EP was very much a sun-worshipper, in Venice, then at Lake Garda and finally in Rapallo. The name Tigullio also recurs in the final lines of canto 116, which is as close as EP ever got to writing a finale to The Cantos . The history of Rapallo goes back to the first century A.D., th ough the oldest remains that have been preserved date from circa 1200 (the ruins of the monasteries of San Tommaso and Valle Christi in the valley behind the town).