Chametz in Eighteen Minutes? an Inquiry Into the Correct Text of the Talmud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

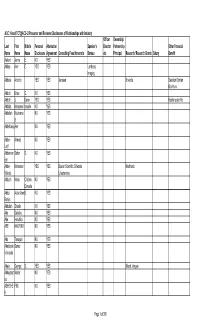

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

I. Maot Chitim II. Ta'anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns III. Chametz

To The Brandeis Community, Many of us have fond memories of preparing for the holiday of Pesach (Passover), and our family's celebration of the holiday. Below is a basic outline of the major halakhic issues for Pesach this year. If anyone has questions they should be in touch with me at h[email protected]. In addition to these guidelines, a number of resources are available online from the major kashrut agencies: ● Orthodox Union: http://oukosher.org/passover/ ○ a pdf of the glossy magazine that’s been seen around campus can be found here ● Chicago Rabbinical Council: link ● Star-K: link Best wishes for a Chag Kasher ve-Sameach, Rabbi David, Ariel, Havivi, and Tiffy Pardo Please note: Since we are all spending Pesach all over the world (literally...I’m selling your chametz for you, I know) please use the internet to get appropriate halakhic times. I recommend m yzmanim.com or the really nifty sidebar on https://oukosher.org/passover/ I. Maot Chitim The Rema (Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayim 429) records the ancient custom of ma'ot chitim – providing money for poor people to buy matzah and other supplies for Pesach. A number of tzedka organizations have special Maot Chitim drives. II. Ta’anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns Erev Pesach is the fast of the firstborns, to commemorate the fact that the Jewish firstborns were spared during m akat bechorot (the slaying of the firstborns). This year the fast is observed on Friday April 3 (14 Nissan) beginning at alot hashachar (i.e. -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Pesach Status of Enriched White Rice Ask Ou

ww ww VOL. y h / NO. 7 IYAR 5771 / MAY 2011 s xc THEDaf a K ashrus a monthlyH newsletter for th e o U r a bb inic field representative DAF NOTES On Sunday, March 27, for the first time, the Harry H. Beren ASK OU OUTREACH Kashrut Shiurim were presented to the Sephardic community at Bnei Shaare Zion in Brooklyn, NY. The OU Poskim, Rav Hershel Schachter and Rav Yisroel Belsky, both discussed the current Pesach status of enriched white rice for those who are permitted to eat Kitniyot on Pesach. These discussions sparked much interest in the Sephardic community. Although by now, Pesach is behind us, the Daf feels it important to share with its readers the research Rabbi Gavriel Price has made on this subject in the article below, as well as the accompanying Teshuva written by Rav Schachter Shlita. Rav Schachter writes in his Teshuva that the potential Chametz in rice that is produced by several major US manufacturers would be Botul before Pesach. How- ever, it is proper for Sephardim to wash the rice to remove the possible Chametz in the added vitamins. It is preferable for Sephardim to use any unprocessed brown rice or white rice with an acceptable Kosher L’Pesach certification as found in Eretz Yisroel, for those permitted to eat Kitniyot. Please refer to the Teshuva for the reasons Rav Schachter gives for these Psokim. Parboiled, pre-cooked, boil-in-a-bag, and converted rice are either pesach statUs naturally enriched or use a special method of enrichment that will of enriched white rice not be discussed here. -

Jerusalem Between Segregation and Integration: Reading Urban Space Through the Eyes of Justice Gad Frumkin

chapter 8 Jerusalem between Segregation and Integration: Reading Urban Space through the Eyes of Justice Gad Frumkin Y. Wallach Introduction Jerusalem is seen as an archetypal example of a divided city, where extreme ethno-national polarization is deep rooted in a long history of segregation. In this chapter I challenge this perception by re-examining urban dynamics of late Ottoman and British Mandate Jerusalem, while questioning the manner in which urban segregation is theorized and understood. In the past few decades, there has been a reinvigorated scholarly discus- sion of urban segregation, driven by the challenges of difference and diversity.1 Entrenched segregation between different groups (defined by race, ethnicity, religion or class), or the “parallel lives” of different communities, living side by side with little contact, are seen to undermine the multicultural model of the late twentieth century. At the same time, mechanistic models of integration through urban mixing are increasingly challenged, and it is no longer accepted as evident that segregation is always undesirable. Nor is it obvious that everyday contact between different communities necessarily helps to engender greater understanding and dialogue. Scholars have been debating how to locate the discussion of urban encounter and segregation in the lived experience of the city. Writing on this topic suffers from the idealization of urban cosmopoli- tanism, on the one hand, or, conversely, describing segregation in overdeter- mined terms. To avoid this double pitfall, closer attention to the historical and spatial context is necessary, as well as close examination of socioeconomic real- ities. One suggestion, that I follow in this chapter, is to focus on life histories.2 By 1 This chapter forms part of ‘Conflict in Cities and the Contested Stated’ project, funded by the esrc’s Large Grants Programme (res-060-25-0015). -

One of My Old Ambitions Was to Put out an English Version of Rabbeinu

One of my old ambitions was to put out an English version of Rabbeinu Chayim HaLevi al HoRambam that made the beauty of Brisker lomdus accessible to those with no yeshiva background – the ArtScroll Rav Chayyim. That’s unlikely to happen at this stage (and perhaps ArtScroll has already found an author), but I thank Ethan Hauser for sending me back to Rav Chayyim this week, and here’s a very rough, and much less accessible, version of what might have been:) 1. Rambam in Laws of Chametz and Matzah 1:3 One does not get lashes for violating lo yeiraeh and lo yimatzei1 unless one acquired chametz on Pesach or else caused something to become chametz, so that one does an action in order to violate, but if one had chametz prior to Pesach, and was not mevaer2 it, but rather left it under one’s authority, even though he violated the two DO NOTs mentioned above, he is not liable to lashes under Biblical law, because he did not do an action in order to violate (lo asah bo maaseh). A. How can Rambam claim that one gets lashes for violating lo yeiraeh and lo yimatzei under any circumstances?! The Talmud on Pesachim 95a says explicitly that these DO NOTs are consider to be nitak to the DO (laaseh) of tashbisu, and the rule is that any DO NOT that is nitak to a DO is not subject to lashes!? a. Other versions of Pesachim 95a make no mention of the issue of nitak laaseh, and rather declare these DO NOT’s to be DO NOT’s not involving actions, perfectly in accordance with Rambam. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in