This Is Not My Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

L'aubette 1928

« L’AUBETTE 1928 » VISITES GUIDÉES Téléchargez gratuitement Place Kléber Possibilité de visites guidées pour l’audio-guide de l’Aubette 1928 : les groupes aux horaires d’ouverture HORAIRES de l’Aubette. Du mercredi au samedi VISITES POUR LES SCOLAIRES de 14h à 18h : R. Aginako Imp. Int. C. U. Strasbourg U. C. Int. Aginako R. Imp. : Mercredis, jeudis et vendredis matin. : M. Bertola, M. : StrasbourgMuséesVille de la de L’AUBETTE 1928 Résa. au 03 88 88 50 50 (du lundi Entrée libre au vendredi de 8h 30 à 12h 30) WWW.MUSEES.STRASBOURG.EU Photos Graphisme L’AUBETTE 1928 BIOGRAPHIES LES ESPACES RESTITUÉS LA RESTAURATION L’AUBETTE 1928 L’AUBETTE ORIGINELLE L’AUBETTE AU XIXE ET DÉBUT DU XXE SIÈCLE L’INITIATIVE DES FRÈRES HORN DESCRIPTIF DU COMPLEXE La réalisation de l’Aubette est confiée en 1765 Après avoir abrité dès 1845 un café dans une Paul Horn réalise de 1922 à 1926 les premiers plans Le complexe de loisirs de l’Aubette comprend alors à l’architecte Jacques-François Blondel (1705- partie de ses locaux, l’Aubette accueille en 1869 intérieurs. Cette même année, les entrepreneurs quatre niveaux (sous-sol, rez-de-chaussée, entresol 1774). Faute de ressources suffisantes, le projet le musée municipal de peintures, créé en 1803, s’adjoignent les compétences de Hans Jean Arp et et premier étage) dont les trois artistes se répar- initial qui comprenait, outre le corps de bâtiment, qui sera ravagé par un incendie le 24 août 1870. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Le couple d’artistes s’associe tissent la décoration. Seuls les espaces du premier le traitement symétrique de la place Kléber, est La réhabilitation du bâtiment intervient entre 1873 en septembre 1926 à Theo Van Doesburg, peintre étage, accueillant le Ciné-bal et la salle des fêtes aux abandonné. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

2 , 31 Octobre 2009 2 , 31 Oktober 2009

les journées de l’architecture architecture en mouvement(s) 2 , 31 octobre 2009 , oktober 2009 oktober 31 2 architektur in bewegung(en) in architektur die architekturtage die Karlsruhe Haguenau Drusenheim Baden-Baden Herrlisheim Mundolsheim Bühl Wiwersheim La Wantzenau Schiltigheim Strasbourg Molsheim Lingolsheim Illkirch- Graffenstaden Offenburg Stuttgart j Saint-Pierre Sélestat Colmar Freiburg im Breisgau Dessenheim Mulhouse Riedisheim Village-Neuf Weil am Rhein Rheinfelden Basel © Google Earth 2008 Il y a mille et une façons de « lire » l’architecture et trois façons de consulter ce programme… À vous de choisir le sommaire qui vous convient : par villes (ci-dessous), par manifestations (pages 2 à 5) ou par dates (en fi n de programme). Architektur lässt sich auf verschiedenste Arten „lesen“ und dieses Programm auf drei… Wählen Sie die Inhaltsübersicht aus, die Ihnen am Besten gefällt: geordnet nach Städten Bühl (siehe unten), nach Veranstaltungen (Seiten 2 bis 5) oder nach Datum (am Ende des Programms). ●F Pour un public francophone | Für französischsprachiges Publikum ●D Pour un public germanophone | Für deutschsprachiges Publikum Sans frontière 12 Baden-Baden 20 Basel 22 Colmar 26 Freiburg im Breisgau 30 Haguenau 40 Karlsruhe 42 Mulhouse 50 Offenburg 54 Schiltigheim 58 Sélestat 62 Strasbourg 70 Wiwersheim 104 + Bühl, Dessenheim, Drusenheim, Herrlisheim, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, Lingolsheim, Molsheim, Mundolsheim, Rheinfelden, Riedisheim, Saint-Pierre, Stuttgart, Village-Neuf, La Wantzenau, Weil am Rhein 2 MANIFESTATIONS | VERANSTALTUNGEN Ouverture | Eröffnung k MULHOUSE 10 Expositions | Ausstellungen Der Osten im Übergang – Grenzen in Bewegung 20 k BADEN-BADEN BBC : bâtiments basse consommation en Alsace 26 k ColmAR EPAPA : petits projets d’architecture des pays d’Alsace 27 k ColmAR Kunst bau werk II, Architektur-Blicke 30 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU Architekturfotografie: Tomas Riehle 31 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU 15. -

The Devk.Opment of an Architecture

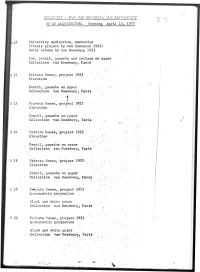

/o n Glir.CKI.IST - THi-.O V.M^ DOESBURG: TIIK DEVKl.OrMEnT OF AH ARCHITECTURli: Opcntng April 10. 1970 3-7 10 University auditorium, Amatcrdam (Thesis project by van Eesteren 1922) Color scheme by van Doesburg 1923 Ink, pencil, gouache and collage on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris ^\ ' IB 12 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris D 13 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris U 14 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris B 15 Private House, project 1923 Elevation ' ' , Pencil, gouache on paper i\ ' Collection van Doesburg, Paris D 19 Pwivatc House, proj.ect 1923 A::onoinetric projection - Black and white print Collection van Doesburg, Paris ^ 20 Private House, project 1923 ' A::onomotrtc projection Black apd vhite print Collection van Doesburg, Paris t •••••• ^ I van Docoburs/2| B 23 Private H0U80, project 1923 A::onoinetrlc projection Dlack and vhlte print vlth gouache and collage Collection van Eesteren, Amstordam B 24 Private House, project 1923 ' Axonomotrtc projection,' Lithosraph , Collection van Doesburg, Paris ..;..: I', B 25 Private House, project 1923 Study for "Counter-Construction" Ink, couache on paper .^i /, Collection van Doesburg, Paris ; B 26 Private House, project 1923 Study for "Counter-Construction" Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris' B 33 Private House, project 1923-24 V • 9> '"Counter-Construction"^ . / . Photomontage ' ' • .* Collection van Doesburg, Paris ; . B 27 Private House, project 1923 •"Counter-Cons truetlorf' Pencil and gouache on paper x Collection van Doesburg, Paris' B 28 Private House, project 1923^ v ' V "Counter-Construction" ! ' . -

Geoff Lucas -- Towards a Concrete

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Towards a Concrete Art A Practice-Led Investigation Lucas, Geoff Award date: 2015 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Towards a Concrete Art: A Practice-Led Investigation Geoff Lucas PhD Fine Art, (Full-time). Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design University of Dundee September 2010 - September 2015 Towards a Concrete Art: A Practice-Led Investigation Geoff Lucas Boyle Family: Loch Ruthven, 2010 Installation view 4 5 Contents 1.33 Can this dialogue operate without representational elements? 96 1.4 HICA Exhibition: Richard Couzins: Free Speech Bubble , 1 March–5 April 2009 98 List of Illustrations 10 1.41 Questioning the location of meaning 98 Abstract 15 1.42 Sign and signified; ‘outer’ and -

BAUHAUS Weimar 1919

Predavanje 7/1 Avant-garde u Holandiji 1917-1932 Pablo PICASSO, Bottle, Glass and Fork 1911-12. KUBIZAM 1907-1912 Picasso Baraque Georges Braque, The Portuguese 1911. HOLLAND De Stijl 1917-1931 Piet Mondrian Neoplasticism: ‘prava plasticna umetnost’ Postoji stara i nova svest vremena. Stara svest je usmerena ka pojedinacnom. Nova je usmerene ka univerzalnom. There is an old and a new consciousness of the age. The old one is directed towards the individual. The new one is directed towards universal.’ Theo van Doesburg Gerrit Rietveld Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, Blue, and Red, 1921, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 69 cm, Tate Gallery. London. Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, Strandboulevard, seaside housing project, Scheveningen, 1917 Theo van Doesburg (R) with Cornelis van Eesteren Theo van Doesburg, Construction de L'Espace-Temps II, detail 1924. Canvas, Oil. Gerrit Rietveld, Red and Blue Chair, 1917. Cornelis van Eesteren, Maison Particuliere, Cornelis van Eesteren, Maison Particuliere, Axonometric Counter-construction, drawing and color scheme by Theo projection and color scheme by Theo Van Doesburg 1923 Van Doesburg 1923. Cornelis van Eesteren, Maison Particuliere, Counter-construction, drawing and color scheme by Theo Van Doesburg 1923. Theo Van Doesburg, Aubette (remodeling), Strasbourg, Cinema and dance hall (destroyed) 1926-1928. Theo Van Doesburg, Aubette (remodeling), Strasbourg, Cinema and dance hall (destroyed, recently reconstructed) ), 1926-1928. Theo van Doesburg, Design for interior decoration of the main hall of a university 1923. Theo van Doesburg, Counter-Composition XVI, 1925. Gerrit Rietveld, Mrs. Truus Schroder House, Utrecht, 1924. Gerrit Rietveld, Mrs. Truus Schroder House, Utrecht, Plan of ground floor 1924. -

De Stijl, One of the Longest Lived and Most Influential Groups of Modern Artists, Was Formed in Holland During the First World War

de stil De Stijl, one of the longest lived and most influential groups of modern artists, was formed in Holland during the first world war. From the very beginning it was marked by extraordinary collaboration on the part of painters and sculptors on the one hand and architects and practical de- signers on the other. It included among its leaders two of the finest artists of the period, the painter Piet Mondrian and the architect J. J. P. Oud; bul its wide influence was exerted principally through the theory and tireless propaganda of its founder, Theo van Doesburg, painter, sculptor, architect, typographer, poet, novelist, critic and lecturer-a man as versatile as any figure of the renaissance. DE STIJLPAINTING, MONDRIAN AND VAN DOESBURG, 1912-1920 Three elements or principles formed the fundamental basis of the work of de Stijl, whether in painting, architecture or sculpture, furniture or typography: in form the rectangle; in color the "primary" hues, red, blue and yellow; in composition the asymmetric balance. These severely simplified elements were not, however, developed in a moment but as the result of years of trial and error on the part of the painters Mondrian, van Doesburg, and van der Leck. Mondrian first studied with his uncle, a follower of Willem Maris. Then, after three years at the Amsterdam Academy, he passed through a period of naturalistic landscapes to a mannered, mystical style resem- bling the work of Thorn-Prikkerand Toorop. By the beginning of 1912 he was in Paris and there very soon fell under the influence of Picasso. Some of his paintings of 1 91 2, based upon tree forms, were as abstract as any Braque or Picasso of that time. -

Maarten Doorman

artinprogress2.def 20-10-2003 11:58 Pagina 1 Maarten Doorman Art is supposed to be of our time or rather to be part of Art in Progress the future. This perspective has reigned the arts and art criticism for more than a century. The author of this challenging and erudite essay shows how the idea of progress in the arts came up A Philosophical Response to the End of the Avant-Garde and he describes the enormous retorical impact of progressive concepts. After the end of the avant-garde the idea of progress in the arts collapsed and soon philosophers like Arthur Danto Doorman Maarten proclaimed the end of art. Doorman investigates the crippling effects of postmodernism on the arts and proposes a new form of progress to understand contemporary art. Its history can still be seen as a process of accumulation: works of art comment on each other, enriching each other’s meanings. These complex interrelationships lead to progress in both the sensibility of the observer and the significance of the works of art. Art in Progress Maarten Doorman is an In the nineteenth century, the history of painting associate professor of was regarded as the paradigm of a progressive under- philosophy at the taking, and evidence that historical progress is a University of Maastricht possible ideal everywhere else. In post-modernist and a professor of literary times, however, progress seems to have all but lost criticism at the University meaning against prevailing philosophies of the end of Amsterdam. The Dutch of art. But the end of art does not entail that there has edition of this title was not been genuine progress in the philosophy of art. -

Booklet (Download PDF)

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Living Abstraction Biography In the first half of the twentieth century, the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber- Arp created a rich and diverse oeuvre bridging the divide between ap- plied and fine arts. Her face will be familiar to most people in Switzer- land, where it appeared on the 50-franc note from 1995 until 2016. This exhibition, which was organized in cooperation with the Museum of Modern Art, New York (Anne Umland, Walburga Krupp), and Tate Modern, London (Natalia Sidlina), seeks to introduce broad international audi- ences to a leading pioneer of abstraction. Davos and Trogen 1889–1908 Early years Sophie Taeuber is born in Davos on January 19, 1889, the youngest child of the pharmacist Emil Taeuber and his wife Sophie Taeuber-Krüsi [→1]. After her father’s death, her mother runs a boardinghouse in Trogen (AR) to provide for the family. She teaches her young daughters various crafts and nurtures the children’s creativity. St. Gallen 1908–1910, Munich 1910–1914 Studying arts and crafts Aged 18, Taeuber-Arp enrolls as an auditor at the Drawing School for Industry and Commerce in St. Gallen. The town has been a center of the textile and embroidery industries, eastern Switzerland’s eco- nomic mainstays, since the mid-nineteenth century. After their mother’s death in 1908, the sisters Sophie and Erika move to St. Gallen. In 1910, Taeuber-Arp leaves for Munich to attend the reform- oriented Debschitz School, where women and men study together [→2]. The training she receives is influenced by the ideals of the British Arts-and-Crafts Movement, which underscores the affinities between manual craftsmanship and artistic creation and envisions an alternative to the “soullessness” of industrial production. -

Europe People’S a of Idea the and Society Civil and Tack on the Open, Cosmopolitan Outlook of Europe

urope - Space for Transcultural Existence? is the first volume of the new se- Eries, Studies in Euroculture, published by Göttingen University Press. The se- ries derives its name from the Erasmus Mundus Master of Excellence Euroculture: Europe in the Wider World, a two year programme offered by a consortium of Studies in Euroculture, Volume 1 eight European universities in collaboration with four partner universities outside 1 Europe. This master highlights regional, national and supranational dimensions of the European democratic development; mobility, migration and inter-, multi- and Europe - Space for transculturality. The impact of culture is understood as an element of political and Transcultural Existence? social development within Europe. The articles published here explore the field of Euroculture in its different ele- ments: it includes topics such as cosmopolitanism, cultural memory and trau- matic past(s), colonial heritage, democratization and Europeanization as well as Edited by Martin Tamcke, Janny de Jong the concept of (European) identity in various disciplinary contexts such as law Lars Klein, Margriet van der Waal and the social sciences. In which way have Europeanization and Globalization in- fluenced life in Europe more specifically? To what extent have people in Europe turned ‘transcultural’? The ‘trans’ is understood as indicator of an overlapping mix of cultures that does not allow for the construction of sharp differentiations. It is explored in topics such as (im)migration and integration, as well as cultural products and lifestyle. The present economic crisis and debt crisis have led, as side-result, to a public at- tack on the open, cosmopolitan outlook of Europe. The values of the multicultural and civil society and the idea of a people’s Europe have become debatable. -

Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20Th Century Sculpture

Hans Arp & Other Masters Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers of 20th Century Sculpture Volume 3 Edited by Elisa Tamaschke, Jana Teuscher, and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 3 Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20th Century Sculpture Edited by Elisa Tamaschke, Jana Teuscher, and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20th Century Sculpture An Introduction Jana Teuscher 20 Negative Space in the Art of Hans Arp Daria Mille 26 Similar, Although Obviously Dissimilar Paul Richer and Hans Arp Evoke Prehistory as the Present Werner Schnell 54 Formlinge Carola Giedion-Welcker, Hans Arp, and the Prehistory of Modern Sculpture Megan R. Luke 68 Appealing to the Recipient’s Tactile and Sensorimotor Experience Somaesthetic Redefinitions of the Pedestal in Arp, Brâncuşi, and Giacometti Marta Smolińska 89 Arp and the Italian Sculptors His Artistic Dialogue with Alberto Viani as a Case Study Emanuele Greco 108 An Old Modernist Hans Arp’s Impact on French Sculpture after the Second World War Jana Teuscher 123 Hans Arp and the Sculpture of the 1940s and 1950s Julia Wallner 142 Sculpture and/or Object Hans Arp between Minimal and Pop Christian Spies 160 Contributors 164 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp is one of the established greats of twentieth-century art. As a founder of the Dada movement and an associate of the Surrealists and Con- structivists alike, as well as co-author of the iconic book Die Kunst-ismen, which he published together with El Lissitzky in 1925, Arp was active at the very core of the avant-garde.