Amanda Speight Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

L'aubette 1928

« L’AUBETTE 1928 » VISITES GUIDÉES Téléchargez gratuitement Place Kléber Possibilité de visites guidées pour l’audio-guide de l’Aubette 1928 : les groupes aux horaires d’ouverture HORAIRES de l’Aubette. Du mercredi au samedi VISITES POUR LES SCOLAIRES de 14h à 18h : R. Aginako Imp. Int. C. U. Strasbourg U. C. Int. Aginako R. Imp. : Mercredis, jeudis et vendredis matin. : M. Bertola, M. : StrasbourgMuséesVille de la de L’AUBETTE 1928 Résa. au 03 88 88 50 50 (du lundi Entrée libre au vendredi de 8h 30 à 12h 30) WWW.MUSEES.STRASBOURG.EU Photos Graphisme L’AUBETTE 1928 BIOGRAPHIES LES ESPACES RESTITUÉS LA RESTAURATION L’AUBETTE 1928 L’AUBETTE ORIGINELLE L’AUBETTE AU XIXE ET DÉBUT DU XXE SIÈCLE L’INITIATIVE DES FRÈRES HORN DESCRIPTIF DU COMPLEXE La réalisation de l’Aubette est confiée en 1765 Après avoir abrité dès 1845 un café dans une Paul Horn réalise de 1922 à 1926 les premiers plans Le complexe de loisirs de l’Aubette comprend alors à l’architecte Jacques-François Blondel (1705- partie de ses locaux, l’Aubette accueille en 1869 intérieurs. Cette même année, les entrepreneurs quatre niveaux (sous-sol, rez-de-chaussée, entresol 1774). Faute de ressources suffisantes, le projet le musée municipal de peintures, créé en 1803, s’adjoignent les compétences de Hans Jean Arp et et premier étage) dont les trois artistes se répar- initial qui comprenait, outre le corps de bâtiment, qui sera ravagé par un incendie le 24 août 1870. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Le couple d’artistes s’associe tissent la décoration. Seuls les espaces du premier le traitement symétrique de la place Kléber, est La réhabilitation du bâtiment intervient entre 1873 en septembre 1926 à Theo Van Doesburg, peintre étage, accueillant le Ciné-bal et la salle des fêtes aux abandonné. -

Gce History of Art Major Modern Art Movements

FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS Major Modern Art Movements Key words Overview New types of art; collage, assemblage, kinetic, The range of Major Modern Art Movements is photography, land art, earthworks, performance art. extensive. There are over 100 known art movements and information on a selected range of the better Use of new materials; found objects, ephemeral known art movements in modern times is provided materials, junk, readymades and everyday items. below. The influence of one art movement upon Expressive use of colour particularly in; another can be seen in the definitions as twentieth Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism, century art which became known as a time of ‘isms’. Cubism, Expressionism, and colour field painting. New Techniques; Pointilism, automatic drawing, frottage, action painting, Pop Art, Neo-Impressionism, Synthesism, Kinetic Art, Neo-Dada and Op Art. 1 FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART / MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS The Making of Modern Art The Nine most influential Art Movements to impact Cubism (fl. 1908–14) on Modern Art; Primarily practised in painting and originating (1) Impressionism; in Paris c.1907, Cubism saw artists employing (2) Fauvism; an analytic vision based on fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. It was like a deconstructing of (3) Cubism; the subject and came as a rejection of Renaissance- (4) Futurism; inspired linear perspective and rounded volumes. The two main artists practising Cubism were Pablo (5) Expressionism; Picasso and Georges Braque, in two variants (6) Dada; ‘Analytical Cubism’ and ‘Synthetic Cubism’. This movement was to influence abstract art for the (7) Surrealism; next 50 years with the emergence of the flat (8) Abstract Expressionism; picture plane and an alternative to conventional perspective. -

Gedächtnisstütze: Eine Gedenktafel Für Eugenie Goldstern (PDF, 5,7

Gedächtnisstütze Eine Gedenktafel für Eugenie Goldstern “In der komplizierten und wechselhaften Geschichte der mitteleuropäischen Staatenwelt stellen Fragen des ‘kollektiven Gedächtnisses’ neue und wichtige Forschungsansätze für das kulturelle Selbstverständnis ihrer Bewohner dar. Historische Gedächtnisorte (lieux de mémoire) dienen, wie dies Pierra Nora und andere im Rahmen von systematischen historischen Forschungen über Frankreich gezeigt haben, der symbolischen Vergegenwärtigung von Menschen und Personen. Sie sollen ein Gruppenbewußtsein schaffen oder erhalten. Die Untersuchung der Inhalte, Formen und Funktionen derartiger Gedächtnisorte (Bauwerke, Denkmäler, Begräbnisse, Straßennamen etc.) kann Hinweise auf Veränderungen der nationalen, religiösen, politischen, kulturellen und staatlichen Identitäten geben. ”1 Auf der Internationalen Tagung der Akademie der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung und der Hebraic Graduate School of Europe in Berlin geht es um „Israel in Europa – Europa in Israel.” Den Schwerpunkt bilden “Die Schoa, die Krise der Geisteswissenschaften und das jüdische Erbe Europas.” Am 21.11.2009 spricht Michel Cullin, Professor für Politikwissenschaft an der Diplomatischen Akademie, Wien über „Eugenie Goldstern und der Frankojudaismus.” Der Kulturausschuss der Stadt Wien beschließt am 7.6.2011, daß Frauen durch Benennung von Straßen, Plätzen oder Parks geehrt werden : „Rosa - Weber - Weg“, „Makebagasse“, „Marianne - Pollak - Gasse“, „Hlawkastraße“, „Polkorabplatz“, „Toskaweg“, „Adelheid-Popp-Park.“2 „Die Tagung soll die kulturphilosophischen, gesellschaftlichen und politischen Aspekte des oben Aufgeführten aus der Perspektive der Schoa, der Krise der Geisteswissenschaften und des Jüdischen Erbes Europas im Spannungsfeld von Israel in Europa und Europa in Israel thematisieren. Die Frage der Verbindung zwischen Religion, Philosophie, Wissenschaft und Kunst wird im Mittelpunkt stehen, auf der Suche nach einer Kulturellen Magna Charta für Europa.”3 “Es war Eugenie Goldstern aus Bukarest, die sich auf die Hochalpen spezialisierte. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

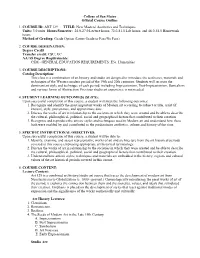

ART 129 New Masters' Aesthetics and Techniques

College of San Mateo Official Course Outline 1. COURSE ID: ART 129 TITLE: New Masters' Aesthetics and Techniques Units: 3.0 units Hours/Semester: 24.0-27.0 Lecture hours; 72.0-81.0 Lab hours; and 48.0-54.0 Homework hours Method of Grading: Grade Option (Letter Grade or Pass/No Pass) 2. COURSE DESIGNATION: Degree Credit Transfer credit: CSU; UC AA/AS Degree Requirements: CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E5c. Humanities 3. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS: Catalog Description: This class is a combination of art history and studio art designed to introduce the aesthetics, materials and techniques of the Western modern period of the 19th and 20th centuries. Students will recreate the dominant art style and technique of each period, including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Surrealism and various forms of Abstraction. Previous studio art experience is not needed. 4. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOME(S) (SLO'S): Upon successful completion of this course, a student will meet the following outcomes: 1. Recognize and identify the most important works of Modern art according to subject or title, artist (if known), style, provenance, and approximate date. 2. Discuss the works of art in relationship to the societies in which they were created and be able to describe the cultural, philosophical, political, social and geographical factors that contributed to their creation. 3. Recognize and reproduce the artistic styles and techniques used in Modern art and understand how these both were enabled by and contributed to the predominate aesthetics, culture and history of the time. 5. SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES: Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to: 1. -

Arabesken – Das Ornamentale Des Balletts Im Frühen 19

2017-10-18 10-58-48 --- Projekt: transcript.anzeigen / Dokument: FAX ID 026f474678049510|(S. 1- 2) VOR2935.p 474678049518 Aus: Eike Wittrock Arabesken – Das Ornamentale des Balletts im frühen 19. Jahrhundert November 2017, 358 Seiten, kart., zahlr. Abb., 39,99 €, ISBN 978-3-8376-2935-4 Die Arabeske ist nicht nur eine der wichtigsten Positionen des klassischen Ballettvo- kabulars, mit ihr lässt sich auch das Ornamentale des Balletts im frühen 19. Jahrhun- dert beschreiben. Aus bisher größtenteils unveröffentlichten ikonografischen Quellen entwickelt Eike Wittrock eine Ästhetik des Balletts, die sowohl die Einzelfigur Arabes- ke wie auch die Gruppenformationen des corps de ballet erfasst. Lithografien, choreo- grafische Notationen, Abbildungen in Traktaten, Musterbücher und Buchverzierun- gen werden dabei als historiografische Medien von Tanz verstanden, die die fantasti- sche Bildlichkeit dieser Ballette in der Aufzeichnung weiterführen. Eike Wittrock ist Tanzwissenschaftler an der Freien Universität Berlin und forscht dort zur Tanzgeschichte. Außerdem arbeitet er als Dramaturg und Kurator im Bereich des zeitgenössischen Tanzes. Weitere Informationen und Bestellung unter: www.transcript-verlag.de/978-3-8376-2935-4 © 2017 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2017-10-18 10-58-48 --- Projekt: transcript.anzeigen / Dokument: FAX ID 026f474678049510|(S. 1- 2) VOR2935.p 474678049518 Inhalt 1. Einleitung | 7 Le Délire d’un peintre: Figur und Fantasie | 11 Zur Methode | 20 Der Begriff Arabeske | 36 Tanzhistorischer Forschungsstand | 53 2. Danseuses d’Herculanum | 65 3. Genealogie der Arabeske | 97 Drei frühe Auftritte der Arabeske | 104 Carlo Blasis’ Theorie der Arabeske | 108 Eingebildete Linien | 131 Of the figure that moves against the wind | 146 Finale Arabeske/Unzählige Variationen | 149 Im Cirque Olympique | 159 Arabesken in Giselle | 168 4. -

The Pseudo-Kufic Ornament and the Problem of Cross-Cultural Relationships Between Byzantium and Islam

The pseudo-kufic ornament and the problem of cross-cultural relationships between Byzantium and Islam Silvia Pedone – Valentina Cantone The aim of the paper is to analyze pseudo-kufic ornament Dealing with a much debated topic, not only in recent in Byzantine art and the reception of the topic in Byzantine times, as that concerning the role and diffusion of orna- Studies. The pseudo-kufic ornamental motifs seem to ment within Byzantine art, one has often the impression occupy a middle position between the purely formal that virtually nothing new is possible to add so that you abstractness and freedom of arabesque and the purely have to repeat positions, if only involuntarily, by now well symbolic form of a semantic and referential mean, borrowed established. This notwithstanding, such a topic incessantly from an alien language, moreover. This double nature (that gives rise to questions and problems fueling the discussion is also a double negation) makes of pseudo-kufic decoration of historical and theoretical issues: a debate that has been a very interesting liminal object, an object of “transition”, going on for longer than two centuries. This situation is as it were, at the crossroad of different domains. Starting certainly due to a combination of reasons, but ones hav- from an assessment of the theoretical questions raised by ing a close connection with the history of the art-historical the aesthetic peculiarities of this kind of ornament, we discipline itself. In the present paper our aim is to focus on consider, from this specific point of view, the problem of a very specific kind of ornament, the so-called pseudo-kufic the cross-cultural impact of Islamic and islamicizing formal inscriptions that rise interesting pivotal questions – hither- repertory on Byzantine ornament, focusing in particular on to not so much explored – about the “interference” between a hitherto unpublished illuminated manuscript dated to the a formalistic approach and a functionalistic stance, with its 10th century and held by the Marciana Library in Venice. -

Abstract Styles in the Vienna Workshop: a Formalist Analysis of Josef Hoffman's

Abstract Styles in the : Vienna Workshop A Formalist Analysis of Josef Hoffman’s Two Designs Asli Arpak Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA [email protected] Abstract A shape grammar formalism is elaborated for the Vienna Workshop (Wiener Werkstaette) designer Josef Hoffmann’s two designs. Early instances of abstract expressionism are traced in Hoffman’s works by investigating stylistic d parallels through shape rules an computations. The analysis of Hoffmann’s two works are carried out in parallel to Terry Knight’s analysis of De Stijl artists Georges Vantongerloo and Fritz Glarner paintings with the normal form grammars. Keywords: Josef Hoffmann; Wiener Werkstaette; shape grammars; style. abstraction; . Introduction In the end of the nineteenth century, many significant Kabaret Fledermaus and ectural the Archit philosophical and artistic movements flourished in Europe that Detailing of Ceramics were fuelled by newly developing universal ideals, changing Kabaret Fledermaus (the Fledermaus Cabaret) was a theatre that political scenes, and ant const scientific and industrial opened in 1907 in the lively Vienna city and it was envisioned to advancements. Subsequent to the French Art Nouveau, be a meeting point for the Vienna avant-‐garde and the impressionism, and the English Arts and Crafts Movement, a large 197 intelligentsia. The cabaret could ee house thr hundred guests and group of Austrian artists and designers started the Vienna its aim was to restore the cabaret culture with an artistic twist. In Workshop (Wiener Werkstaette) in 1903 nerian with the Wag ideal addition to restaging classical plays with new décor and costumes, Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork). the Vienna Workshop artists were also producing novel Various great Austrian architects, artists, and designers were performances. -

Michael Steinbach Rare Books

Michael Steinbach Rare Books Freyung 6/4/6 – A – 1010 Vienna – Austria – Phone: +43-664-3575948 Mail: [email protected] – www.antiquariat-steinbach.com Books to be exhibited at the 51st California International Antiquarian Book Fair Pasadena Convention Center 330 E. Green St. Pasadena CA91101 - February 9-11 Please visit my booth 825 or order directly by email – Prices are net in €uros ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Alastair - Wilde, Oscar. The Sphinx. Illustrated and decorated by Alastair. London, John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1920. 31:23 cm. 10 tissue-garded plates, 2 plates before the endpapers, 13 decorated initials all in turquoise and black, by Alastair, 36 pages, Original cream cloth with gilt and turquoise illustration on front cover, gilt title on spine, top edge gilt, others untrimmed. 750, -- First Alastair edition, elaborately decorated with illustrations by Baron Hans-Henning von Voight (1887-1969), who published under the pseudonym of Alastair. One of 100 copies. - Spine very little rubbed, otherwise a fine copy. 2 Altenberg - Oppenheimer, Max. Peter Altenberg. Für die AKTION gezeichnet von Max Oppenheimer. Berlin, Die Aktion, o.J. 14,5 : 9,5 cm. 80, -- Zeit den Kopf Peter Altenbergs nach links mit seiner Signatur in Faksimile. - Werbepostkarte für die Zeitschrift 'Die Aktion'. Die Berliner Wochenzeitung DIE AKTION sei empfohlen, denn sie ist mutig ohne Literatengefecht, leidenschaftlich ohne Phrase und gebildet ohne Dünkel. (Franz Blei in 'Der lose Vogel'). 3 Andersen, Hans Christian. Zwölf mit der Post. Ein Neujahrsmärchen. Vienna Schroll (1919) 11 : 9,5 cm. With 12 coloured plates by Berthold Löffler. Illustrated original boards with coloured end-papers by B. -

2 , 31 Octobre 2009 2 , 31 Oktober 2009

les journées de l’architecture architecture en mouvement(s) 2 , 31 octobre 2009 , oktober 2009 oktober 31 2 architektur in bewegung(en) in architektur die architekturtage die Karlsruhe Haguenau Drusenheim Baden-Baden Herrlisheim Mundolsheim Bühl Wiwersheim La Wantzenau Schiltigheim Strasbourg Molsheim Lingolsheim Illkirch- Graffenstaden Offenburg Stuttgart j Saint-Pierre Sélestat Colmar Freiburg im Breisgau Dessenheim Mulhouse Riedisheim Village-Neuf Weil am Rhein Rheinfelden Basel © Google Earth 2008 Il y a mille et une façons de « lire » l’architecture et trois façons de consulter ce programme… À vous de choisir le sommaire qui vous convient : par villes (ci-dessous), par manifestations (pages 2 à 5) ou par dates (en fi n de programme). Architektur lässt sich auf verschiedenste Arten „lesen“ und dieses Programm auf drei… Wählen Sie die Inhaltsübersicht aus, die Ihnen am Besten gefällt: geordnet nach Städten Bühl (siehe unten), nach Veranstaltungen (Seiten 2 bis 5) oder nach Datum (am Ende des Programms). ●F Pour un public francophone | Für französischsprachiges Publikum ●D Pour un public germanophone | Für deutschsprachiges Publikum Sans frontière 12 Baden-Baden 20 Basel 22 Colmar 26 Freiburg im Breisgau 30 Haguenau 40 Karlsruhe 42 Mulhouse 50 Offenburg 54 Schiltigheim 58 Sélestat 62 Strasbourg 70 Wiwersheim 104 + Bühl, Dessenheim, Drusenheim, Herrlisheim, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, Lingolsheim, Molsheim, Mundolsheim, Rheinfelden, Riedisheim, Saint-Pierre, Stuttgart, Village-Neuf, La Wantzenau, Weil am Rhein 2 MANIFESTATIONS | VERANSTALTUNGEN Ouverture | Eröffnung k MULHOUSE 10 Expositions | Ausstellungen Der Osten im Übergang – Grenzen in Bewegung 20 k BADEN-BADEN BBC : bâtiments basse consommation en Alsace 26 k ColmAR EPAPA : petits projets d’architecture des pays d’Alsace 27 k ColmAR Kunst bau werk II, Architektur-Blicke 30 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU Architekturfotografie: Tomas Riehle 31 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU 15.