Flesh and Blood Educator Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lanfranco's Camerino Degli Eremiti and the Meaning of Landscape Around 1600

m kw Arnold A. Witte THE ARTFUL HERMITAGE THE PALAZZETTO FARNESE AS A COUNTER-REFORMATION DIAETA <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ARNOLD A. WITTE The Artful Hermitage The Palazzetto Farnese as a Counter-reformation Diaeta Copyright 2008 © <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER Via Cassiodoro, 19 - 00193 Roma http://www.lerma.it Progetto grafico: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER Tutti i diritti riservati. E' vietata la riproduzione di testi e ifiustrazioni senza II permesso scritto dell'Editore. Wine, Arnold A. The artful hermitage : the Palazzetto Farnese as a counter-reformation diaeta / Arnold A. Witte. - Roma <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, 2008 - 206 p. : ill. ; 31 cm. - (LemArte ; 2) ISBN 978-88-8265-477-1 CDD 21. 728.820945632 1. Roma - Palazzetto Farnese - Camerino degli Eremiti 2. Roma - Palazzetto Farnese - Storia 3. Pittura - Roma - Sec. 17. This publication of this book was made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Stichting Charema, Amsterdam. Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS pag. 7 INTRODUCTION: LANFRANCO'S CA1vIEFJN0 DEGLI EREMITI AND THE MEANING OF LANDSCAPE AROUND1600 ............................................................ >> 9 1. TYPOLOGY AND DECORATION OF THE PALAZZETTO ............................... >> 23 Camerino and Palazzetto: a reconstruction .................................. >> 27 Decoration of the Palazzetto .............................................. >> 29 The giardino segreto as 'theatre of nature' ................................... >> 38 The typology of studioli ................................................. -

Barbara Ramasco

Responsabile divisione restauro della Carbone Costruzioni BARBARA RAMASCO Curriculum Vitae Nata a Roma il 25 Marzo 1958. Dal 1981 svolge attività di restauro e conservazione dei beni culturali specializzandosi nei seguenti settori: • Dipinti murali • Dipinti su tela • Dipinti su tavola • Manufatti lapidei • Cortina laterizia • Intonaci • Statue lignee policrome • Mosaici • Decorazioni in stucco ed in gesso • Rifacimento intonaci secondo le tecniche antiche • Tinteggiature a calce secondo le tecniche antiche Titoli di studio e formazione professionale Diploma Maturità Scientifica conseguito presso l’Istituto Archimede di Roma a.s. 1977/1978 Apprendistato presso i cantieri di restauro del Prof. Gianluigi Colalucci 1980-1981 Corso di aggiornamento professionale effettuato presso l’Università del Disegno – Docente Professor Gaspare De Fiore a.s. 1992-93 Corso di aggiornamento professionale “Controlli non distruttivi e metodologie diagnostiche applicate al restauro” a cura di .A.G.U. – Ministero Beni Culturali -Soprintendenza Beni Artistici e Storici di Roma 1993 Corso di aggiornamento professionale “Principi teorici dei metodi di pulitura chimici e fisici a cura dei Professori M. Coladonato – U. Santamaria – F. Malarico 1996 Restauratrice qualificata ai sensi del D.M. 294 del 03.08.2000 e successive modifiche e Integrazioni Attività lavorative 1981-1982 Apprendistato presso la ditta Gianluigi Colalucci 1982 Inizia l’attività in qualità di Ditta Individuale Barbara Ramasco associandosi o collaborando con le seguenti ditte di restauro: Annamaria Sorace; Cecilia Bernardini; Cooperativa C.B.C. 1983-1991 Socia fondatrice del Consorzio “CRBC Eleazar” – Presidente Gianluigi Colalucci 1991-1992 Associazione in partecipazione con le Ditte Simone Colalucci e Luigia Gambino 1994 Associazione in partecipazione con le Ditte Simone Colalucci e Paola Vitagliano 1995 Collaborazione con la Ditta Lia Breschi 1995-1998 Collaborazione con la S.E.I. -

1 Caravaggio and a Neuroarthistory Of

CARAVAGGIO AND A NEUROARTHISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT Kajsa Berg A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia September 2009 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior written consent. 1 Abstract ABSTRACT John Onians, David Freedberg and Norman Bryson have all suggested that neuroscience may be particularly useful in examining emotional responses to art. This thesis presents a neuroarthistorical approach to viewer engagement in order to examine Caravaggio’s paintings and the responses of early-seventeenth-century viewers in Rome. Data concerning mirror neurons suggests that people engaged empathetically with Caravaggio’s paintings because of his innovative use of movement. While spiritual exercises have been connected to Caravaggio’s interpretation of subject matter, knowledge about neural plasticity (how the brain changes as a result of experience and training), indicates that people who continually practiced these exercises would be more susceptible to emotionally engaging imagery. The thesis develops Baxandall’s concept of the ‘period eye’ in order to demonstrate that neuroscience is useful in context specific art-historical queries. Applying data concerning the ‘contextual brain’ facilitates the examination of both the cognitive skills and the emotional factors involved in viewer engagement. The skilful rendering of gestures and expressions was a part of the artist’s repertoire and Artemisia Gentileschi’s adaptation of the violent action emphasised in Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes testifies to her engagement with his painting. -

Sant Agostino

(078/31) Sant’Agostino in Campo Marzio Sant'Agostino is an important 15th century minor basilica and parish church in the rione Sant'Eustachio, not far from Piazza Navona. It is one of the first Roman churches built during the Renaissance. The official title of the church is Sant'Agostino in Campo Marzio. The church and parish remain in the care of the Augustinian Friars. The dedication is to St Augustine of Hippo. [2] History: The convent of Sant’Agostino attached to the church was founded in 1286, when the Roman nobleman Egidio Lufredi donated some houses in the area to the Augustinian Friars (who used to be called "Hermits of St Augustine" or OESA). They were commissioned by him to erect a convent and church of their order on the site and, after gaining the consent of Pope Honorius IV, this was started. [2] Orders to build the new church came in 1296, from Pope Boniface VIII. Bishop Gerard of Sabina placed the foundation stone. Construction was to last nearly one and a half century. It was not completed until 1446, when it finally became possible to celebrate liturgical functions in it. [2] However, a proposed church for the new convent had to wait because of its proximity to the small ancient parish church of San Trifone in Posterula, dedicated to St Tryphon and located in the Via della Scrofa. It was a titular church, and also a Lenten station. In 1424 the relics of St Monica, the mother of St Augustine, were brought from Ostia and enshrined here as well. -

Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy

Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy by Colin Alexander Murray A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Colin Murray 2016 Collaborative Painting Between Minds and Hands: Art Criticism, Connoisseurship, and Artistic Sodality in Early Modern Italy Colin Alexander Murray Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The intention of this dissertation is to open up collaborative pictures to meaningful analysis by accessing the perspectives of early modern viewers. The Italian primary sources from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries yield a surprising amount of material indicating both common and changing habits of thought when viewers looked at multiple authorial hands working on an artistic project. It will be argued in the course of this dissertation that critics of the seventeenth century were particularly attentive to the practical conditions of collaboration as the embodiment of theory. At the heart of this broad discourse was a trope extolling painters for working with what appeared to be one hand, a figurative and adaptable expression combining the notion of the united corpo and the manifold meanings of the artist’s mano. Hardly insistent on uniformity or anonymity, writers generally believed that collaboration actualized the ideals of a range of social, cultural, theoretical, and cosmological models in which variously formed types of unity were thought to be fostered by the mutual support of the artists’ minds or souls. Further theories arose in response to Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s hypothesis in 1590 that the greatest painting would combine the most highly regarded old masters, each contributing their particular talents towards the whole. -

Rowland Charles Mackenzie Phd Thesis

THE SOUND OF COLOUR : THE INTELLECTUAL FOUNDATIONS OF DOMENICHINO'S APPROACH TO MUSIC AND PAINTING Rowland Charles MacKenzie A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 1998 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/15247 This item is protected by original copyright Rowland Charles MacKenzie The Sound of Colour: The Intellectual Foundations of Domenichino's Approach to Music and Painting. Part One Master of Philosophy Thesis, University of St Andrews Submitted on March 31st 1998. ProQuest Number: 10167222 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10167222 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 b 'u £ \ DECLARATIONS I, Rowland Charles MacKenzie, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 78,000 words in length has been written by me, that it is a record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. -

Galerie Canesso Tableaux Anciens

Galerie Canesso Tableaux anciens GIOVANNI BATTISTA BEINASCHI fossano, c. 634 naples, 688 Saint Paul oil on canvas, 49 ¹⁄₄ × 39 ³⁄₈ in ⁽25 × 00 cm⁾ as indicated by a label glued into the back of the picture at an early date,1 our Saint Paul was accompanied by a Saint Peter,2 its likely pendant, with which it shared the same history until they were both put up for public auction in 990. Francesco Petrucci has confirmed the authorship of Beinaschi, publishing the work in the addenda section of the monograph he co-wrote with Vincenzo Pacelli. According to the scholar, the canvas was painted when the artist was still in his early period, in about 660. Indeed, the style is not yet influenced by Neapolitan painting, instead displaying an enduring link with Giovanni Lanfranco (582-647) and Gian Domenico Cerrini (609-68). The saint is depicted frontally, an open book on his lap and his right hand raised heavenward: one can imagine him in the midst of a sermon. The cold light, in dynamic contrast with areas of shadow, lends drama to the figure, and the absence of setting and the presence of ample draperies show close adherence to the Baroque style. Beinaschi was trained in Turin, his native region, and then in Rome, where he made copies after Annibale Carracci and Giovanni Lanfranco. He settled in Naples in 664 and remained there until his death. In 677-678 he returned to Rome to work with Giacinto Brandi on the decoration of the Basilica of Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 1, Winter 2018

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 1, Winter 2018 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association Society of Architectural Historians International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts Scholars Committee member Tenley Bick, exploring the theme of “Processi italiani: Examining Process in Postwar March 21, 2017 Italian Art, 1945-1980.” The session was well-attended, inspired lively discussion between the audience and Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: speakers, and marks our continued successful expansion into the fields of modern and contemporary Italian Art. Dario As I get ready to make the long flight to New Donetti received a Conference Travel Grant for Emerging Orleans for RSA, I write to bring you up to date on our Scholars to present his paper “Inventing the New St. Peter’s: recent events, programs, and awards and to remind you Drawing and Emulation in Renaissance Architecture.” The about some upcoming dates for the remainder of this conference also provided an opportunity for another in our academic year and summer. My thanks are due, as series of Emerging Scholars Committee workshops, always, to each of our members for their support of the organized by Kelli Wood and Tenley Bick. IAS and especially to all those who so generously serve CAA also provided the venue for our annual the organization as committee members and board Members Business Meeting. Minutes will be available at the members. IAS website shortly, but among the topics discussed were Since the publication of our last Newsletter, our the ongoing need for more affiliate society sponsored members have participated in sponsored sessions at sessions at CAA, the pros and cons of our current system of several major conferences, our 2018 elections have taken voting on composed slates of candidates selected by the place, and several of our most important grants have Nominating Committee, the increasingly low attendance of been awarded. -

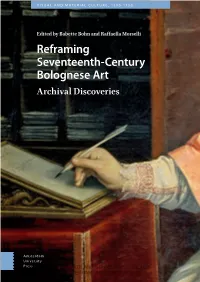

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Bohn & Morselli (eds.) Edited by Babette Bohn and Raffaella Morselli Reframing Seventeenth-CenturySeventeenth-century Bolognese Art Archival Discoveries Reframing Seventeenth-Century Bolognese Art Bolognese Seventeenth-Century Reframing FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Reframing Seventeenth-Century Bolognese Art FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Reframing Seventeenth-Century Bolognese Art Archival Discoveries Edited by Babette Bohn and Raffaella Morselli Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Guido Reni, Portrait of Cardinal Bernardino Spada, Rome, Galleria Spada, c. -

The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Dissertations and Theses 2009 Velázquez: The pS anish Style and the Art of Devotion Lawrence L. Saporta Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/dissertations Custom Citation Saporta, Lawrence L. "Velázquez: The pS anish Style and the Art of Devotion." Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College, 2009. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/dissertations/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Velázquez: The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion. A Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Department of the History of Art Bryn Mawr College Submitted by Lawrence L. Saporta Advisor: Professor Gridley McKim-Smith © Copyright by Lawrence L. Saporta, 2009 All Rights Reserved Dissertation on Diego Velázquez Saporta Contents. Abstract Acknowledgements i Image Resources iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Jesuit Art Patronage and Devotional Practice 13 Chapter 2. Devotion, Meditation, and the Apparent Awkwardness of Velázquez’ Supper at Emmaus 31 Chapter 3. Velázquez’ Library: “an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries” 86 Chapter 4 Technique, Style, and the Nature of the Image 127 Chapter 5 The Formalist Chapter 172 Chapter 6 Velázquez, Titian, and the pittoresco of Boschini 226 Synthesis 258 Conclusion 267 Works Cited 271 Velázquez: The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion. Lawrence L. Saporta, Ph.D. Bryn Mawr College, 2009 Supervisor: Gridley McKim-Smith This dissertation offers an account of counter-reformation mystical texts and praxis with art historical applicability to Spanish painting of the Seventeenth Century— particularly the work of Diego Velázquez. -

Lectionary Texts for August 2, 2020 •Ninth Sunday After Pentecost - Year a Genesis 32:22-31 • Psalm 17:1-7, 15 • Romans 9:1-5 • Matthew 14:13-21

Lectionary Texts for August 2, 2020 •Ninth Sunday after Pentecost - Year A Genesis 32:22-31 • Psalm 17:1-7, 15 • Romans 9:1-5 • Matthew 14:13-21 Matthew 14:13-21 The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, 1624-1625 by Giovanni Lanfranco, Italian, 1582-1647 Oil on canvas National Gallery of Ireland, On-Line Collection, Dublin, Ireland Lanfranco created many religious decorations for churches and palaces in Rome. This paint- ing is one of eight canvases on the theme of the Eucharist that he produced for a chapel in the Basilica of Saint Paul Fuori le Mura (Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls) there. Considered one of Lanfranco’s most successful achievements, the cycle is a re-affirmation of the Counter Refor- mation dogma of the real presence of the body of Christ in the sacrament of the Eucharist, the loaves foreshadowing the sacramental bread. The painting style is one where the content volume was important; thus, numerous clearly delineated figures as well as light and shadows predominate. Slightly off-center, Jesus is pointing to the bread, and the crowd, drawn in detail, is responding in many different ways — moving, pointing, surprised, agitated, pleading. Born in Parma, Italy, Lanfranco received independent commissions in Rome as early as his 20’s, and he and another artist engaged in a rivalry for the main fresco commissions. He was fairly eclectic in terms of style but preferred a visionary, theatrical approach for the ceiling paintings that were gaining in popularity in the early 17th century. He become the pre-eminent painter of the circle of Pope Paul V. -

FB Catalogue Final.Pdf

Seattle, Seattle Art Museum Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum October 17 2019 - January 26 2020 March 01 2020 - June 14 2020 Curated by Sylvain Bellenger with the collaboration of Chiyo Ishikawa, George Shackleford and Guillaume Kientz Embassy of Italy Washington The Embassy of Italy in Washington D.C. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte Seattle Art Museum Director Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO Front cover Sylvain Bellenger Amada Cruz Parmigianino Lucretia Chief Curator Susan Brotman Deputy Director for Art and 1540, Oil on panel Linda Martino Curator of European Painting and Sculpture Naples, Museo e Real Bosco Chiyo Ishikawa di Capodimonte Exhibition Department Patrizia Piscitello Curatorial Intern Exhibition Catalogue Giovanna Bile Gloria de Liberali Authors Documentation Department Deputy Director for Art Administration Sylvain Bellenger Alessandra Rullo Zora Foy James P. Anno Christopher Bakke Head of Digitalization Exhibitions and Publications Manager Proofreading and copyediting Carmine Romano Tina Lee Mark Castro Graphic Design Restoration Department Director of Museum Services Studio Polpo Alessandra Golia and Chief Registrar Lauren Mellon Photos credits Legal Consulting Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte Studio Luigi Rispoli Associate Registrar for Exhibitions © Alberto Burri by SIAE 2019, Fig. 5 Megan Peterson © 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation American Friends of Capodimonte President for the Visual Arts by SIAE, Fig. 6 Nancy Vespoli Director of Design and Installation Photographers Nathan Peek and his team Luciano Romano Speranza Digital Studio, Napoli Exhibition Designer Paul Martinez Published by MondoMostre Printed in Italy by Tecnostampa Acting Director of Communications Finished printing on September 2019 Cindy McKinley and her team Copyright © 2019 MondoMostre Chief Development Ofcer Chris Landman and his team All Rights Reserved.