Whither French Socialism?*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Social Dialogue the History of a Social Innovation (1985-2003) — Jean Lapeyre Foreword by Jacques Delors Afterword by Luca Visentini

European Trade Union Institute Bd du Roi Albert II, 5 1210 Brussels Belgium +32 (0)2 224 04 70 [email protected] www.etui.org “Compared to other works on the European Social Dialogue, this book stands out because it is an insider’s story, told by someone who was for many years the linchpin, on the trade unions’ side, of this major accomplishment of social Europe.” The European social dialogue — Emilio Gabaglio, ETUC General Secretary (1991-2003) “The author, an ardent supporter of the European Social Dialogue, has put his heart and soul into this The history of a social meticulous work, which is enriched by his commitment as a trade unionist, his capacity for indignation, and his very French spirit. His book will become an essential reference work.” — Wilfried Beirnaert, innovation (1985-2003) Managing Director and Director General at the Federation of Belgian Enterprises (FEB) (1981-1998) — “This exhaustive appraisal, written by a central actor in the process, reminds us that constructing social Europe means constructing Europe itself and aiming for the creation of a European society; Jean Lapeyre something to reflect upon today in the face of extreme tendencies which are threatening the edifice.” — Claude Didry, Sociologist and Director of Research at the National Centre of Scientific Research (CNRS) Foreword by Jacques Delors (Maurice Halbwachs Centre, École Normale Supérieure) Afterword by Luca Visentini This book provides a history of the construction of the European Social Dialogue between 1985 and 2003, based on documents and interviews with trade union figures, employers and dialogue social European The The history of a social innovation (1985-2003) Jean Lapeyre European officials, as well as on the author’s own personal account as a central actor in this story. -

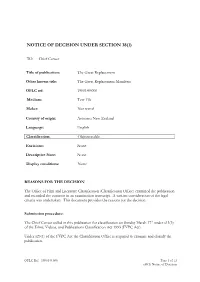

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

Lionel Jospjn

FACT SHEET N° 5: CANDIDATES' BIOGRAPHIES LIONEL JOSPJN • Lionel Jospin was born on 12 July 1937 in Meudon (Houts de Seine). The second child in a family of four, he spent his whole childhood in the Paris region, apart from a period during the occupation, and frequent holidays in the department of Tam-et-Garonne, from where his mother originated. First a teacher of French and then director of a special Ministry of Education school for adolescents with problems, his father was an activist in the SFIO (Section franr;aise de l'intemationale ouvrierej. He was a candidate in the parliamentary elections in l'lndre in the Popular Front period and, after the war, the Federal Secretary of the SFIO in Seine-et-Marne where the family lived. Lionel Jospin's mother. after being a midwife, became a nurse and school social worker. EDUCATION After his secondary education in Sevres, Paris, Meaux and then back in Paris, lionel Jospin did a year of Lettres superieures before entering the Paris lnstitut d'efudes politiquesin 1956. Awarded a scholarship, he lived at that time at the Antony cite universitaire (student hall of residence). It was during these years that he began to be actively involved in politics. Throughout this period, Lionel Jospin spent his summers working as an assistant in children's summer camps (colonies de vacances'J. He worked particularly with adolescents with problems. A good basketball player. he also devoted a considerable part of his time to playing this sport at competitive (university and other) level. After obtaining a post as a supervisor at ENSEP, Lionel Jospin left the Antony Cite universifaire and prepared the competitive entrance examination for ENA. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Populism, Political Culture, and Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French Presidential Election*

Eleven The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology VOLUME 9 2018 CREATED BY UNDERGRADUATES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Editors-in-Chief Laurel Bard and Julia Matthews Managing Editor Michael Olivieri Senior Editors Raquel Zitani-Rios, Annabel Fay, Chris Chung, Sierra Timmons, and Dakota Brewer Director of Public Relations Juliana Zhao Public Relations Team Katherine Park, Jasmine Monfared, Brittany Kulusich, Erika Lopez-Carrillo, Joy Chen Undergraduate Advisors Cristina Rojas and Seng Saelee Faculty Advisor Michael Burawoy Cover Artist Kate Park Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology is the annual publication of Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology, a non-profit unincorporated association at the University of California, Berkeley. Grants and Financial Support: This journal was made possible by generous financial support from the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Special Appreciation: We would also like to thank Rebecca Chavez, Holly Le, Belinda White, Tamar Young, and the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Contributors: Contributions may be in the form of articles and review essays. Please see the Guide for Future Contributors at the end of this issue. Review Process: Our review process is double-blind. Each submission is anonymized with a number and all reviewers are likewise assigned a specific review number per submission. If an editor is familiar with any submission, she or he declines to review that piece. Our review process ensures the highest integrity and fairness in evaluating submissions. Each submission is read by three trained reviewers. Subscriptions: Our limited print version of the journal is available without fee. If you would like to make a donation for the production of future issues, please inquire at [email protected]. -

Assemblée Nationale Sommaire

A la découverte de l’Assemblée nationale Sommaire Petite histoire d’une loi (*) ................................... p. 1 à lexique parlementaire ............................................. p. 10 à ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE Secrétariat général de l’Assemblée et de la Présidence Service de la communication et de l’information multimédia www.assemblee-nationale.fr Novembre 2017 ^ Dessins : Grégoire Berquin Meme^ si elle a été proposée par une classe participant au Parlement des enfants en 1999, la loi dont il est question dans cette bande dessinée n’existe pas. Cette histoire est une fiction. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Groupe politique Ordre du Jour lexique Un groupe rassemble des députés C’est le programme des travaux de qui ont des affinités politiques. l’Assemblée en séance publique. parlementaire Les groupes correspondent, Il est établi chaque semaine par en général, aux partis politiques. la Conférence des Présidents, composée des vice-présidents de Guignols l’Assemblée, des présidents de Tribunes situées au-dessus des deux commission et de groupe et d’un Amendement Commission portes d’entrée de la salle des représentant du Gouvernement. Proposition de modification d’un Elle est composée de députés séances. Elle est présidée par le Président projet ou d’une proposition de loi représentant tous les groupes Journal officiel de l’Assemblée. Deux semaines de soumise au vote des parlementaires. politiques. Elle est chargée d’étudier séance sur quatre sont réservées en L’amendement supprime ou modifie et, éventuellement, de modifier les Le Journal Officiel de la République priorité aux textes présentés par le un article du projet ou de la projets et propositions de loi avant française publie toutes les décisions de Gouvernement. -

Fonds De L'union Démocratique Et Socialiste De La Résistance

Fonds de l'Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance. Vol. 2 (1945-1965) Inventaire semi-analytique (412AP/35-412AP/67) Par N. Faure Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1979-1981 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_004946 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2010 par l'entreprise diadeis dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 412AP/35-412AP/67 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Fonds de l'Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance. Parties 4-6 : élections ; correspondance - interventions ; François Mitterrand. Date(s) extrême(s) 1945-1965 Nom du producteur • Bourdan, Pierre (1909-1948) • Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance (France ; 1945-1964) Localisation physique Pierrefitte DESCRIPTION Type de classement L'inventaire a été établi par la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques : à son système de cotation propre (cotes "x UDSR x"), ont donc succédé les cotes des Archives nationales (412AP/xx). Liens : Liens annexes : Voir l'annexe jointe • Table de concordance entre les cotes attribuées par la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques et celles des Archives nationales (412AP) Abréviations utilisées dans l'instrument de recherche : Dr : Dossier l.s. : lettre signée l.a.s. : lettre autographe signée l.dact.s. : lettre dactylographiée signée n.s. : non signé s.d. : sans date man. : manuscrit dact. : dactylographié SOURCES ET REFERENCES Sources complémentaires Liens : Liens IR : 3 Archives nationales (France) • Fonds de l'Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance. -

The Ideas of Economists and Political Philosophers, Both When They Are Right and When They Are Wrong, Are More Powerful Than Is Commonly Understood

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. J. M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (chapter 24, §V). The evolution of the international monetary and financial system: Were French views determinant? Alain Alcouffe (University of Toulouse) alain.alcouffe@ut‐capitole.fr Fanny Coulomb (IEP Grenoble) Anthony M. Endres in his 2005 book, has stressed the part player by some economists in the design of the international monetary system during the Bretton Woods era. He proposed a classification of their doctrines and proposals in a table where fifteen economists are mentioned for ten proposals (Hansen, Williams , Graham, Triffin, Simons, Friedman/Johnson, Mises/Rueff/ Heilperin/Hayek/Röpke, Harrod, Mundell). Among them only one French economist, Jacques Rueff, is to be found but he did not stand alone but merged with those of other « paleo‐liberals ». At the opposite, in his 2007 book, Rawi Abdelal pointed the predominant part played by French citizens in the evolution of the international monetary system during the last decades, especially during the building up of the euro area and the liberalization of the capital movements. The article outlines the key stages in the evolution of the international monetary system and the part played by French actors in the forefront of the scene (Jacques Delors – European commission, Pascal Lamy, WTO) or in the wings (Chavranski, OECD). -

Composition De L'assemblée Nationale Française Par Législature - Wikipédia

Composition de l'Assemblée nationale française par législature - Wikipédia http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_de_l%27Assembl%C3%A9e... Voici la composition de l'Assemblée nationale française par législature depuis 1789. France 1 Hémicycles 1.1 Troisième République Cet article fait partie de la série sur 1.2 GPRF et Quatrième République la 1.3 Cinquième république 2 Composition politique de la France, 2.1 Révolution française sous-série sur la politique. 2.1.1 États généraux (1789) 2.1.2 Assemblée nationale constituante (1789-1791) 2.1.3 Assemblée nationale législative (1791-1792) Cinquième République 2.1.4 Première République-Convention nationale (1792-1795) Constitution 2.1.5 Les Conseils (1795-1799) Conseil constitutionnel 2.2 Consulat et Premier Empire (1800-1814) Pouvoir exécutif 2.3 Première Restauration (1814-1815) Président de la République 2.4 Cent-Jours (1815) Premier ministre 2.5 Seconde Restauration (1815-1830) Gouvernement Administration centrale 2.6 Monarchie de Juillet (1830-1848) Pouvoir législatif 2.7 Deuxième République Parlement : 2.7.1 Assemblée nationale constituante (1848-1849) Assemblée nationale 2.7.2 Assemblée nationale législative (1849-1852) (composition) 2.8 Second Empire Sénat Collectivités territoriales 2.8.1 1852-1857 Conseil régional 2.8.2 1857-1863 Conseil général 2.8.3 1863-1869 Commune 2.8.4 1869-1870 Élections 2.9 Troisième République (1871-1940) Présidentielle 2.9.1 Assemblée nationale (1871-1876) Législatives Sénatoriales 2.9.2 1876-1877 Régionales 2.9.3 1877-1881 Cantonales 2.9.4 1881-1885 Territoriales -

Monde.20011122.Pdf

EN ÎLE-DE-FRANCE a Dans « aden » : tout le cinéma et une sélection de sorties Demandez notre supplément www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17674 – 7,90 F - 1,20 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE -- JEUDI 22 NOVEMBRE 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Afghanistan : les débats de l’après-guerre b Quels étaient les buts de la guerre, quel rôle pour les humanitaires ? b « Le Monde » donne la parole à des intellectuels et à des ONG b Conférence à Berlin sur l’avenir de l’Afghanistan, sous l’égide de l’ONU b Le reportage de notre envoyée spéciale en territoire taliban SOMMAIRE formation d’un gouvernement pluriethnique. Les islamistes étran- BRUNO BOUDJELAL/VU b Guerre éclair, doute persistant : gers de Kunduz encerclée risquent Dans un cahier spécial de huit d’être massacrés. Kaboul retrouve a REPORTAGE pages, Le Monde donne la parole à le goût des petites libertés, mais un spécialiste du droit d’ingéren- une manifestation de femmes a ce, Mario Bettati, et à deux person- été interdite. Notre envoyée spé- Une petite ville nalités de l’humanitaire, Rony ciale en territoire taliban, Françoi- Brauman et Sylvie Brunel. Ils disent se Chipaux, a rencontré des popula- leur gêne ou leur inquiétude tions déplacées qui redoutent l’Al- POINTS DE VUE en Algérie devant le rôle que les Etats-Unis liance du Nord. p. 2 et 3 font jouer aux ONG. Des intellec- L’ÉCRIVAIN François Maspero tuels français, Robert Redeker, b La coalition et l’humanitaire : Le Cahier a passé le mois d’août dans une Jean Clair, Daniel Bensaïd et Willy Pentagone compte sur l’Alliance petite ville de la côte algéroise. -

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Review of GERMANY 64th session, 24 September - 12 October 2018 INTERNATIONALE FRAUENLIGA FÜR WOMEN’S INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE FOR FRIEDEN UND FREIHEIT PEACE & FREEDOM DEUTSCHLAND © 2018 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the publishing organisation; the text is not altered, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. 1ST EDITION AUGUST 2018 Design and layout: WILPF www.wilpf.org // www.ecchr.eu Contents I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Germany’s extraterritorial obligations in relation to austerity measures implemented in other countries ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 4 III. Increased domestic securitisation ............................................................................................ 5 a) Steep increase in demands for ‘small’ licences for weapons ............................................................... 5 b) Increase in anti-immigrant sentiments .............................................................................................. -

Comparison of Constitutionalism in France and the United States, A

A COMPARISON OF CONSTITUTIONALISM IN FRANCE AND THE UNITED STATES Martin A. Rogoff I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 22 If. AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM ..................... 30 A. American constitutionalism defined and described ......................................... 31 B. The Constitution as a "canonical" text ............ 33 C. The Constitution as "codification" of formative American ideals .................................. 34 D. The Constitution and national solidarity .......... 36 E. The Constitution as a voluntary social compact ... 40 F. The Constitution as an operative document ....... 42 G. The federal judiciary:guardians of the Constitution ...................................... 43 H. The legal profession and the Constitution ......... 44 I. Legal education in the United States .............. 45 III. THE CONsTrrTION IN FRANCE ...................... 46 A. French constitutional thought ..................... 46 B. The Constitution as a "contested" document ...... 60 C. The Constitution and fundamental values ......... 64 D. The Constitution and nationalsolidarity .......... 68 E. The Constitution in practice ...................... 72 1. The Conseil constitutionnel ................... 73 2. The Conseil d'ttat ........................... 75 3. The Cour de Cassation ....................... 77 F. The French judiciary ............................. 78 G. The French bar................................... 81 H. Legal education in France ........................ 81 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................