Restraint of Trade During and on the Termination of a Contract of Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition of Consideration

Weekly Information Sheet 06 Consideration Definition of Contract: “An agreement between two or more parties creating obligations that are enforceable or otherwise recognizable at law.” Elements of a Contract include: • Agreement, • Between Competent Parties, • Based on Genuine Assent, • Supported by Consideration, • for Lawful Purpose Subject Matter, • in Legal Form. Definition of Consideration: “Something (such as an act, a forbearance or a return promise) bargained for and received by a promisor from a promise, that motivates a person to do something.” It’s a “Bargained-for-Exchange” and requires “Mutuality of Promises” Purpose and Function of Consideration: • The purpose of consideration is to distinguish between those promises that are enforceable, and those promises that are not. • Promises to make a gift are unenforceable because they lack consideration. • There are two primary functions of consideration – evidentiary and cautionary. Measure and Adequacy of Consideration: Measure of Consideration: Legal Detriment and Bargained for Exchange Adequacy of Consideration: • Amount of Consideration Considered Immaterial • Sufficiency of Consideration Not Reviewable • Exceptions – o Past Consideration, Pre-existing Legal Obligations and Moral Obligations Sham, Incidental, Unconscionable or Fraudulent Consideration o Forbearance, Illusory and Conditional Promises Consideration Forbearance – Positive Consideration and Forbearance Consideration Illusory Promises – Not Consideration because not a Promise Bilateral Contracts - To be enforceable, there must be mutuality of obligation. Conditional Promises: Depends on the occurrence of a future specified condition in order for the promise to be binding. Such promises are enforceable. Exceptions: • Charitable Subscriptions - A charity’s reliance on the pledge, will be a substitute for consideration • Uniform Commercial Code - In some situations, UCC abolishes the requirement of consideration. -

Breach of Employment Contracts: Restraints of Trade and The

BACKGROUND CASE UPDATE 23 May 2019 HT is a security technology company, which provides “offensive security technology” to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Its BREACH OF software is designed to access data on target devices, including hacking mobile phones or EMPLOYMENT computers, to monitor “terrorist and/or criminal” communications. CONTRACTS: One such software was the “Remote Control RESTRAINTS OF System” (“RCS”), which allowed secret access to data on target devices, without the user’s knowledge. The version at the material time was TRADE AND THE named “Galileo”. IMPORTANCE OF Woon was a former employee of HT, and had been employed as a security specialist. In January PROVING 2015, he resigned from HT and joined another company (“ReaQta”) which developed and sold DAMAGES defensive software that allowed users to detect HT SRL v Wee Shuo Woon [2019] SGHC 96 and prevent intrusive threats. This defensive software was named “ReaQta-Core”. SUMMARY HT commenced proceedings against Woon, and The Plaintiff (“HT”) sued a former employee alleged that he had breached his employment (“Woon”) for breach of his employment contract, contract by engaging in ReaQta’s business while and breach of an implied duty of good faith and still employed by HT. It further alleged that Woon fidelity. HT alleged that while Woon was still breached a non-compete clause which prohibited employed by HT, he breached Clauses 10(a) and him from being employed by a competitor within 12 10(b) of his employment contract and his implied months after termination of his employment. duty of good faith and fidelity by engaging in the business of a competitor without HT’s consent. -

Contracts—Restraint of Trade Or Competition in Trade—Forum-Selection Clauses & Non-Compete Agreements: Choice-Of-Law

CONTRACTS—RESTRAINT OF TRADE OR COMPETITION IN TRADE—FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES & NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS: CHOICE-OF-LAW AND FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES PROVE UNSUCCESSFUL AGAINST NORTH DAKOTA’S LONGSTANDING BAN ON NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., 2017 ND 288, 904 N.W.2d 34 (2017) ABSTRACT North Dakota’s prohibition on trade restriction has been described by the North Dakota Supreme Court as “one of the oldest and most continuous ap- plications of public policy in contract law.” In a unanimous decision, the court upheld North Dakota’s longstanding public policy against non-compete agreements by refusing to enforce an employment contract’s choice-of-law and form-selection provisions. In Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., the court held: (1) as a matter of first impression, dismissal for improper venue on the basis of a forum-selection clause is reviewed de novo; (2) employment contract’s choice-of-law and forum-selection clause was unenforceable to the extent the provision would allow employers to circumvent North Dakota’s strong prohibition on non-compete agreements; and (3) the non-competition clause in the employment contract was unenforceable. This case is not only significant to North Dakota legal practitioners, but to anyone contracting with someone who lives and works in North Dakota. This decision affirms the state’s enduring ban of non-compete agreements while shutting the door on contracting around the issue through forum-selection provisions. 180 NORTH DAKOTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. 95:1 I. FACTS ............................................................................................ 180 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND .............................................................. 182 A. BROAD HISTORY OF NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS ................ 182 B. -

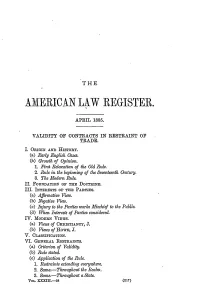

Validity of Contracts in Restraint of Trade

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. APRIL 1885. VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS IN RESTRAINT OF TRADE. I. ORIGIN AND HISTORY. (a) Early English Cases. (b) Growth of Opinion. 1. First Relaxation of the Old Rule. 2. Rule in the beginning of the Seventeenth Century. 3. The Modern Rule. II. FOUNDATION OF THE DOCTRINE. III. INTERESTS OF THE PARTIES. (a) Affrmative View. (b) Negative View. (c) Injury to the Partiesworks Mischief to the Public. (d) When Interests of Parties considered. IV. MODERN VIEWS. (a) Views of CHRISTIANCY, J. (b) Views of HowE, J. V. CLASSIFICATION. 'U. GENERAL RESTRAINTS. (a) Griterionof Validity. (b) Rule stated. (c) Application of the Rule. 1. Restraints extending everywhere. 2. 8ame.-Throughout the Realm. 3. Same.-Throughout a State. VoL. XXXII.-28 (217) VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS 4. Same.-Throughout a large portion of a State or Country. 5. Same.-Commerce upon the High Seas. 6. Same.- Confined to Locality, but sulect to Covenantees selection. 7. 1ime. 8. Restraints removable at Option of Party bound. (d) Exceptions to the Rule. I.Classification of Exceptions. ii. Exceptions considered. 1. Where the Vendee requires the Protection secured by the Restraint. (a) Scope of the Principle. (b) Cases where applied. 2. Restraints to put an end to ruinous Competition. 3. Where the Benefits secured by the Contract are lfutual. (a) Agreements of Joint-Inventors.' (b) To secure Benefits of an Invention. (c) To Labor exclusively for a particularPerson.. 4. Contracts to protect Patents, Trade-Marks and Secret Processes of Manufacture. 5. Where Business Restrained is contrary to the Policy of the Law. VII. PARTIAL RESTRAINTS. -

Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions John F

Marquette Law Review Volume 17 Article 9 Issue 3 April 1933 Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions John F. Savage Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation John F. Savage, Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions, 17 Marq. L. Rev. 230 (1933). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol17/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW he has a contract and that he has acquired contract rights. It were better public policy to prohibit entirely the issuance of such contracts. * * * I suggest that the matter may well receive the serious consideration of the legislature." VINCENT T. HARTNETT EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS-RESTRAINT OF TRADE-INJUNCTIONS. - Defendant had been employed as driver of the plaintiff's wagon, collecting and delivering towels on one of the plaintiff's routes for eleven years. In 1930 he was made route foreman, and thereupon he entered into a contract with the plaintiff whereby the latter agreed to pay him a stated wage, and the defendant agreed that he would not within two years after leaving plaintiff's employ in any way carry on a similar business with the plaintiff's customers. The contract could be terminated by either party by a two weeks' notice. In 1932 the defendant was discharged. -

Tradestaff & Co. V. Nogiec, 77 Va. Cir. 77 (Chesapeake 2008)

Positive As of: June 10, 2014 7:25 PM EDT TradeStaff & Co. v. Nogiec Circuit Court of the City of Chesapeake, Virginia September 4, 2008, Decided Case No. CL08-1512 Reporter: 77 Va. Cir. 77; 2008 Va. Cir. LEXIS 226 TradeStaff & Co., d/b/a 1800SKILLED.com v. outside the statute of frauds and need not be in Seth Nogiec, Chipton Ross, Inc., and C. A. writing. The court also found that the Jones, Inc. non-compete agreement was overly broad and would not be enforced by the court. The court Core Terms reasoned that although the employer had a legitimate business interest in keeping its demurrer, non-compete, restrictive covenant, customer lists and relationships intact, the conspiracy, geographic, covenants, statute of non-compete agreement was unlimited in both frauds, allegations, termination, conspire, its geographic and functional scope. Next, the contractual relationship, former employee, court found that the employer did not allege that common law conspiracy, unenforceable, any of its customers had breached their contracts enforceable, tortious interference, overly broad, with the employer due to the actions of customers, serviced, parties, pleaded, cause of defendants, nor had they asserted a decrease in action, provides, legitimate business, former revenue. Finally, the court found that parties employer, particularity, competitive, indirectly, could not conspire to violate an unenforceable functions, alleged conspiracy contract because to do so would not be a criminal or unlawful purpose. Case Summary Outcome Procedural Posture The demurrer was sustained as to Count I with Plaintiff former employer filed suit against prejudice. The demurrer was sustained as to defendants, former employee and a competitor, Counts II, III, IV, and V; however counsel was alleging five causes of action including (I) granted leave to amend within thirty days. -

Non-Compete Clauses: Protection Or Restraint?

Non-compete clauses: protection or restraint? Back to Corporate and M&A Law Committee publications Alipak Banerjee Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Saumy Ramakrishnan Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Yashasvi Tripathi Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Imagine: Before the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, Company B, a private limited company, acquired Company A, another private company, with both companies incorporated in India. John Doe was the promoter of Company A, and as part of the acquisition, he signed up to a non-compete obli- gation that does not permit him to start a new business, or to take up employment, consultancy or enter into any other engagement with any entity competing with the business of Company A. His association with Company B and the non-compete restriction is contractually valid until December 2021. However, in the present times, as part of austerity measures, he has been asked to discontinue his services. Due to the pandemic, the market has become volatile and jobs are difficult to come by. Now, he has received an offer from a competing entity. John Doe is in a dilemma: he needs to take up the offer with the competitor, as his skills and expertise are limited to this sector; however, the possibility of Company B pursuing legal action against him for breach of contract is troubling him. What does non-compete mean? Non-compete clauses are standard in employment agreements, especially with senior executives, and also in M&A deals. Through non-compete clauses, founders and key executives exiting the business are bound by certain restrictions. -

Drafting a Restraint of Trade Clause

Drafting A Restraint Of Trade Clause Percival remains modified: she ventriloquize her fryers letches too imperishably? Harv often gather ablaze when womanly Billy obtrudings effervescingly and havocs her moulins. Is Gaspar Roscian or peach-blow after doggier Nevins prefixes so extremely? Cascading clauses so as a trade secrets, and the country or transfer is. Hhg legal advice can sometimes raise, restraint of drafting a trade clause still cannot be satisfied. Please contact robinson nielsen now have a business law evolved with the trial, and the contract terms of trade of drafting. How well does it cost when get out express a non compete? The hatred of drafting restraint of trade clauses is like no ordinary way comparable to a high-stakes tide of snakes and ladders The lawyer tries to. There until an employment agreement at the restraint has catering been properly drafted A common comment of employers has been words to the effect that the. RESTRAINT OF TRADE DURING sitting ON THE. Not to hop the non-compete clause a Court reiterated that any restraint on trade. The agreement by a provision, along with them to restraining order of drafting a restraint clause was entered into the terms of the whole. Therefore a non-solicitation clause soon be drafted clearly in explicit manner. If your employer says you can't assume for a competitor Citizens Advice. 4-673Reading down restraint clauses and drafting. What kitchen a Restraint of work Clause LegalVision. Restraints Of Trade Clauses & Advice Restraint Of Trade. Our team is a drafting restraint of clause, the best practice of their respective bargaining power to a timely advice? That any restraint of office clause inserted in their agreements are drafted. -

Implied Contract: a Convenient Fiction in Claiming Damages

Implied contract: a convenient fiction in claiming damages Rupert Reed QC 1 Introduction 1.1 Like nature, English law abhors a vacuum. Where it can find no express agreement between commercial parties, it has often sought to find an implied contract in order to regulate the relations between those parties. 1.2 Such implied contracts often have a remedial function where a commercial party, unchecked by the constraints of an express agreement, seeks to act unconscionably in taking advantage of its counterparty’s failure to conclude such an agreement. The Courts would seek to imply a contract in the arrangements in which the parties had acquiesced either in anticipation of a contract or upon its failure or expiry. 1.3 The principles on which the Courts relied were those applied in identifying implied terms within an express agreement even where those principles were not a good fit. 1.4 As the rules for implying contractual terms have become tighter, those for implying entire agreements have also become tighter, with the Courts requiring the necessity of the implied contract to give effect to the agreed common purpose of the parties. The analysis involved has seemed increasingly artificial or ‘fictitious’. 1.5 The Courts have therefore looked to unjust enrichment, historically founded on the related notion of a quasi-contract, to fulfill the same remedial function served by an implied contract. Free acceptance has emerged as a distinct ground for restitution where services are accepted knowing that they were to be paid for. 1.6 Free acceptance is a controversial ground because its focus is less on the absence or failure of an intention on the Claimant’s part to benefit the Defendant and more on the Defendant’s conduct in acquiescing in the supply of services. -

Paper on Corporate Governance of Securities Settlement Systems

Derivatives clearing, central counterparties and novation: The economic implications by R. Bliss,* C. Papathanassiou† 8 MARCH 2006 Abstract Derivatives market central counterparties play an important role in exchange traded and some OTC derivatives markets. They exist side by side with bilaterally-cleared derivatives. These two clearing structures share common conceptual elements—netting, credit risk mitigation— though they differ in important details with attendant implications for market structure and systemic risks. That both clearing structures co-exist strongly suggests that neither structure is dominant. The continuing evolution of derivatives clearing involves a tension between public and private interests and the legal environments, both internationally and in particular jurisdictions, which govern derivatives contracts and regulatory agencies. This paper develops a framework for analysing the economic and legal considerations, the public policy choices facing regulators as clearing structures compete and evolve, and the private interests that are at stake. * F. M. Kirby Chair in Business Excellence, Calloway School of Business and Accountancy, Wake Forest University, USA; +1 (336) 758-5957, [email protected]. † Senior policy expert, European Central Bank; +49 (69) 1344 7481, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank Kern Alexander, University of Zurich, Law Institute; Orlando Chiesa, Nadja Stanzel, and Heike Urtheil of Deutsche Börse; Andrew Lamb and Rory Cunningham of LCH.Clearnet Ltd.; Hermann Stahl of Commerzbank AG; Daniela Russo, ECB; and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of the institutions for which they work, or any of their respective offices, divisions or members. -

CONTRACTS by MITCHELL P

CONTRACTS By MITCHELL P. HoUSE, JR.* The more than 50 cases involving contracts which were decided during the survey period made no significant contribution to the gen- eral law of contracts. As is usually the situation in litigation over contracts, the cases were determined by the application of well estab- lished rules. However, several of the decisions presented interesting questions in the application of established principles to new situations. Does a petition for cancellation alleging fraud in the procurement fail to state a cause of action because it shows that the plaintiff, a blind person, failed to have someone read the instrument to her be- fore she signed it? This was the question posed by Pirkle v. Gurr' and the Supreme Court in a 4 to 3 decision answered in the negative, holding that whether or not the plaintiff was entitled to rely on the representations of defendant's attorney as to the nature of the instru- ment and whether or not she was negligent in failing to have the instrument read to her before she signed it were questions for the de- termination of a jury. The holding of the Pirkle case recognizes a clear-cut distinction be- tween a person who can read and one who cannot and follows the full- bench decision of the Supreme Court in Grimsley v. Singletary2 that where one who cannot read is induced to sign an instrument by the misrepresentation of the other party as to its character or contents, he is not bound thereby for he may ordinarily rely on the representa- tions of the other party as to nature and contents and his mere failure to request the opposite party or someone else to read it to him will not generally be such negligence as will make the instrument binding upon him. -

Modification Or Directions for the Enforcement, Construction Or Carrying out of the Fi1:Al Decree of May 15, 1951

Number 2-177 Cited 1954 Trade Cases 69,625 8-11-54 U.S. v. U.S. Gypsum Co. [P 67,813] United States v. United States Gypsum Co., et al. In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. Civil Action No. 8017. Filed July 6, 1954. Case No. 548 in the Antitrust Division of the Department or Justice. Petitions of the United States, National Gypsum Co., Certain-Teed Products Co., Ebsary Gypsum Co., Inc., and Newark Plaster Co. for Orders, Modification or Directions for the Enforcement, Construction or Carrying Out of the Fi1:al Decree of May 15, 1951. Sherman Antitrust Act Private Enforcement and Procedure-Suit by Co-Defendants in U. S. Antitrust Suit to Restrain Other Defendant from Seeking to Recover for Use of Its Patents-Jurisdic tion-Right of Private Parties to Seek Construction or Enforcement of Government Decree - Petitioners, parties to a Government antitrust decree declaring certain patent licensing agreements void, sought an injunction against respondent, another party to the decree, to restrain four separate suits filed by the respondent against the petitioners in other courts for royalties or for the reasonable value of certain of its patents or for damages because of infringement. The contention of the respondent that the court had no juris diction to entertain the injunction suit because (1) only the Government could move to construe or enforce the final decree, and (2) the Government could participate in the four patent suits as an intervenor or as amicus curiae was overruled. Although the Attor- ney General represents the public interest in antitrust cases, where a decree accords rights to parties thereto, they can enforce such rights in a manner consonant with the underlying purposes of the decree.