Contract Law and Freedom of Speech Alan E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition of Consideration

Weekly Information Sheet 06 Consideration Definition of Contract: “An agreement between two or more parties creating obligations that are enforceable or otherwise recognizable at law.” Elements of a Contract include: • Agreement, • Between Competent Parties, • Based on Genuine Assent, • Supported by Consideration, • for Lawful Purpose Subject Matter, • in Legal Form. Definition of Consideration: “Something (such as an act, a forbearance or a return promise) bargained for and received by a promisor from a promise, that motivates a person to do something.” It’s a “Bargained-for-Exchange” and requires “Mutuality of Promises” Purpose and Function of Consideration: • The purpose of consideration is to distinguish between those promises that are enforceable, and those promises that are not. • Promises to make a gift are unenforceable because they lack consideration. • There are two primary functions of consideration – evidentiary and cautionary. Measure and Adequacy of Consideration: Measure of Consideration: Legal Detriment and Bargained for Exchange Adequacy of Consideration: • Amount of Consideration Considered Immaterial • Sufficiency of Consideration Not Reviewable • Exceptions – o Past Consideration, Pre-existing Legal Obligations and Moral Obligations Sham, Incidental, Unconscionable or Fraudulent Consideration o Forbearance, Illusory and Conditional Promises Consideration Forbearance – Positive Consideration and Forbearance Consideration Illusory Promises – Not Consideration because not a Promise Bilateral Contracts - To be enforceable, there must be mutuality of obligation. Conditional Promises: Depends on the occurrence of a future specified condition in order for the promise to be binding. Such promises are enforceable. Exceptions: • Charitable Subscriptions - A charity’s reliance on the pledge, will be a substitute for consideration • Uniform Commercial Code - In some situations, UCC abolishes the requirement of consideration. -

Breach of Employment Contracts: Restraints of Trade and The

BACKGROUND CASE UPDATE 23 May 2019 HT is a security technology company, which provides “offensive security technology” to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Its BREACH OF software is designed to access data on target devices, including hacking mobile phones or EMPLOYMENT computers, to monitor “terrorist and/or criminal” communications. CONTRACTS: One such software was the “Remote Control RESTRAINTS OF System” (“RCS”), which allowed secret access to data on target devices, without the user’s knowledge. The version at the material time was TRADE AND THE named “Galileo”. IMPORTANCE OF Woon was a former employee of HT, and had been employed as a security specialist. In January PROVING 2015, he resigned from HT and joined another company (“ReaQta”) which developed and sold DAMAGES defensive software that allowed users to detect HT SRL v Wee Shuo Woon [2019] SGHC 96 and prevent intrusive threats. This defensive software was named “ReaQta-Core”. SUMMARY HT commenced proceedings against Woon, and The Plaintiff (“HT”) sued a former employee alleged that he had breached his employment (“Woon”) for breach of his employment contract, contract by engaging in ReaQta’s business while and breach of an implied duty of good faith and still employed by HT. It further alleged that Woon fidelity. HT alleged that while Woon was still breached a non-compete clause which prohibited employed by HT, he breached Clauses 10(a) and him from being employed by a competitor within 12 10(b) of his employment contract and his implied months after termination of his employment. duty of good faith and fidelity by engaging in the business of a competitor without HT’s consent. -

Simon and Garfunkel.Pptx

Simon & Garfunkel Created by Group 2 Kao-wei Chen, Rebecca Galarowicz, Bri@any Kelly, David Oberg, Nikolas Sell Kao-wei Chen Why Simon & Garfunkel? They were one of the first folk performers make it big in the music industry and became future role models for the upcoming generaon of folk rock singers. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SimonandGarfunkel.jpg Background Informaon • Real Names • Paul Simon • Art Garfunkel • Both were born 1941, sll alive today • First met each other in elementary school • Realized their potenKal when singing together Doo-wop songs found on the radio at an early age h@p://www.last.fm/music/Simon+&+Garfunkel/ +images/138461 Beginning of Simon & Garfunkel • At age 16, they recorded their first single composed by Simon Ktled ‘’Hey Schoolgirl’’ • Peaked at the top 50 on the Billboard under Tom & Jerry • Late 50s/early 60s- both worked together ocassionally but were solo acts during this me • 1964, release of their debut album ‘’Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.’’ • release did poorly • 1964-1965, Tom Wilson, a folk-rock producer, revised Simon’s & Garfunkel’s track Ktled ‘’The Sound of Silence’’ and released it in the market • Track rose to #1 in 1965 • Song was edited by incorporang electric bass, guitar and drums The High & End Life of S&G v 1966, placed 3 albums and four singles in the top 30 of the Billboard v E.g. ‘’The Sound of Silence’’, ‘’I Am A Rock’’, and ‘’Parsely, Sage, Rosemary & Thyme’’ v 1966-1969, their career was at a turning point v WriKng of songs and recording significantly took longer v Simon’s & Garfunkel’s -

Deception in Weight-Loss Advertising Workshop

DECEPTION IN WEIGHT-LOSS ADVERTISING WORKSHOP: Seizing Opportunities and Building Partnerships to Stop Weight-Loss Fraud A Federal Trade Commission Staff Report December 2003 Federal Trade Commission TIMOTHY J. MURIS, Chairman MOZELLE W. THOMPSON, Commissioner ORSON SWINDLE, Commissioner THOMAS B. LEARY, Commissioner PAMELA JONES HARBOUR, Commissioner This is a report of the Bureau of Consumer Protection of the Federal Trade Commission. The views expressed in this report are those of the staff and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Trade Commission or any individual Commissioner. The Commission has voted to authorize the staff to publish this report. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Offi ce of the Surgeon General Rockville MD 20857 We are witnessing a growing epidemic of obesity in this country. This epidemic not only costs this nation over $117 billion a year, but it also steals 300,000 lives. Unfortunately, there is no miracle pill that can help Americans lose excess weight, so we have to rely on responsible behavior – including eating right and being physically active. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity, released in December 2001, called upon almost every segment of the public and private sectors to work together to help Americans make healthy eating and physical activity choices. By improving our nation’s “health literacy” we can ensure that Americans have the information and tools they need to make effective decisions that will improve their overall health and lead to longer, healthier lives. The media can play an important role in educating consumers by providing accurate information about weight loss programs and weight management products. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE NOMINEES ANNOUNCED FOR THE 47TH ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS 2-Hour CBS Special Airs Friday, June 26 at 8p ET / PT NEW YORK (May 21, 2020) — The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 47th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards, which will be presented in a two-hour special on Friday, June 26 (8:00-10:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. The full list of nominees is available at https://theemmys.tv/daytime. “Now more than ever, daytime television provides a source of comfort and continuity made possible by these nominees’ dedicated efforts and sense of community,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO of NATAS. “Their commitment to excellence and demonstrated love for their audience never cease to brighten our days, and we are delighted to join with CBS in celebrating their talents.” “As a leader in Daytime, we are thrilled to welcome back the Daytime Emmy Awards,” said Jack Sussman, Executive Vice President, Specials, Music and Live Events for CBS. “Daytime television has been keeping viewers engaged and entertained for many years, so it is with great pride that we look forward to celebrating the best of the genre here on CBS.” The Daytime Emmy® Awards have recognized outstanding achievement in daytime television programming since 1974. The awards are presented to individuals and programs broadcast between 2:00 am and 6:00 pm, as well as certain categories of digital and syndicated programming of similar content. This year’s awards honor content from more than 2,700 submissions that originally premiered in calendar-year 2019. -

Narrative Time and Mental Space in the Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects 8-2020 Architecture of the Mind : Narrative Time and Mental Space in The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge Monica Cecilia Winston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons ABSTRACT This thesis explores three of director Mike Nichols’s films produced during the New Hollywood period—The Graduate (1967), Catch-22 (1970), and Carnal Knowledge (1971)—in an effort to trace Nichols’s auteur signature as it relates to the depiction of the protagonist’s subjectivity and renders post-war male anxiety and existential dread. In addition to discussing formal film technique used to depict the mental space of the protagonist, how these subjective sequences are implemented in the film bears implications on the narrative form and situates Nichols alongside other New Hollywood directors who were influenced by art cinema. This analysis, like those posited by other critics influenced by film theorist David Bordwell, distinguishes the term “art cinema” as employing a range of techniques outside of continuity editing that are read as stylistic, and because of this it entails specific modes of viewership in order to find meaning in style. Because of the function of style, the thesis posits thematic kinship among The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge, which enriches the film’s respective meanings when viewed side by side. MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY Architecture of the Mind: Narrative Time and Mental Space in The Graduate, Catch-22, and Carnal Knowledge by Monica Cecilia Winston A Master’s Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Montclair State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts August 2020 College: College of Humanities and Social Sciences Department: English Dr. -

Contracts—Restraint of Trade Or Competition in Trade—Forum-Selection Clauses & Non-Compete Agreements: Choice-Of-Law

CONTRACTS—RESTRAINT OF TRADE OR COMPETITION IN TRADE—FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES & NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS: CHOICE-OF-LAW AND FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES PROVE UNSUCCESSFUL AGAINST NORTH DAKOTA’S LONGSTANDING BAN ON NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., 2017 ND 288, 904 N.W.2d 34 (2017) ABSTRACT North Dakota’s prohibition on trade restriction has been described by the North Dakota Supreme Court as “one of the oldest and most continuous ap- plications of public policy in contract law.” In a unanimous decision, the court upheld North Dakota’s longstanding public policy against non-compete agreements by refusing to enforce an employment contract’s choice-of-law and form-selection provisions. In Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., the court held: (1) as a matter of first impression, dismissal for improper venue on the basis of a forum-selection clause is reviewed de novo; (2) employment contract’s choice-of-law and forum-selection clause was unenforceable to the extent the provision would allow employers to circumvent North Dakota’s strong prohibition on non-compete agreements; and (3) the non-competition clause in the employment contract was unenforceable. This case is not only significant to North Dakota legal practitioners, but to anyone contracting with someone who lives and works in North Dakota. This decision affirms the state’s enduring ban of non-compete agreements while shutting the door on contracting around the issue through forum-selection provisions. 180 NORTH DAKOTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. 95:1 I. FACTS ............................................................................................ 180 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND .............................................................. 182 A. BROAD HISTORY OF NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS ................ 182 B. -

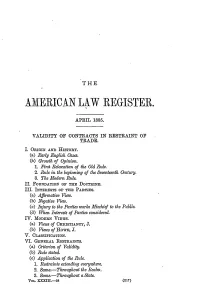

Validity of Contracts in Restraint of Trade

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. APRIL 1885. VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS IN RESTRAINT OF TRADE. I. ORIGIN AND HISTORY. (a) Early English Cases. (b) Growth of Opinion. 1. First Relaxation of the Old Rule. 2. Rule in the beginning of the Seventeenth Century. 3. The Modern Rule. II. FOUNDATION OF THE DOCTRINE. III. INTERESTS OF THE PARTIES. (a) Affrmative View. (b) Negative View. (c) Injury to the Partiesworks Mischief to the Public. (d) When Interests of Parties considered. IV. MODERN VIEWS. (a) Views of CHRISTIANCY, J. (b) Views of HowE, J. V. CLASSIFICATION. 'U. GENERAL RESTRAINTS. (a) Griterionof Validity. (b) Rule stated. (c) Application of the Rule. 1. Restraints extending everywhere. 2. 8ame.-Throughout the Realm. 3. Same.-Throughout a State. VoL. XXXII.-28 (217) VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS 4. Same.-Throughout a large portion of a State or Country. 5. Same.-Commerce upon the High Seas. 6. Same.- Confined to Locality, but sulect to Covenantees selection. 7. 1ime. 8. Restraints removable at Option of Party bound. (d) Exceptions to the Rule. I.Classification of Exceptions. ii. Exceptions considered. 1. Where the Vendee requires the Protection secured by the Restraint. (a) Scope of the Principle. (b) Cases where applied. 2. Restraints to put an end to ruinous Competition. 3. Where the Benefits secured by the Contract are lfutual. (a) Agreements of Joint-Inventors.' (b) To secure Benefits of an Invention. (c) To Labor exclusively for a particularPerson.. 4. Contracts to protect Patents, Trade-Marks and Secret Processes of Manufacture. 5. Where Business Restrained is contrary to the Policy of the Law. VII. PARTIAL RESTRAINTS. -

Komparace Pojetí Hudebního Díla V Autorskoprávní a Muzikologické Oblasti Reflexe; K Aktuálním Problémům a Podobám Hudebního Plagiátu Ve 20

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci Katedra muzikologie Mgr. et Mgr. Václav Kramář Komparace pojetí hudebního díla v autorskoprávní a muzikologické oblasti reflexe; k aktuálním problémům a podobám hudebního plagiátu ve 20. století. Comparison of the Conception of Musical Work in the Copyright and Musicological Area of Reflection; About the Contemporary Problems and Forms of Plagiarism in Music in the 20th century Disertační práce Školitel: Doc. PhDr. Lenka Křupková, Ph. D. Olomouc 2012 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. V Chrudimi 24. 12. 2012 ............................................ Václav Kramář Děkuji Doc. PhDr. Lence Křupkové, Ph. D., své školitelce v doktorském studiu, za trpělivost a rady při vzniku této práce. Poděkování patří rovněž Antonínu Foltýnovi, BcA. Veronice Chlebkové, MgA. Marku Keprtovi, Ph. D., Mgr. Zdeňce Myškové, Mgr. Martinu Thorovskému, Petru Turoňovi, Mgr. Mileně Vašíčkové a celé mé rodině. Obsah1 Obsah ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Úvod ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Stav bádání a pojetí naší reflexe ......................................................................................... 12 1 Terminologické vymezení hudebního díla..................................................................... 21 1.1 K obecným definicím -

Labor Songs: the Provocative Product of Psalmists, Prophets, and Poets

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 50 Number 1 Volume 50, 2011, Numbers 1&2 Article 12 Labor Songs: The Provocative Product of Psalmists, Prophets, and Poets Raymond A. Franklin David L. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LABOR SONGS: THE PROVOCATIVE PRODUCT OF PSALMISTS, PROPHETS, AND POETS RAYMOND A. FRANKLINt & DAVID L. GREGORY* The words of the prophets are written on subway walls and tenement halls. "The Sounds of Silence," Simon & Garfunkel' [The Rolling Stones are] the most dangerous rock-and-roll band in the world. Life, Keith Richards and James Fox2 A singing movement is a winning movement.3 Attributed to, inter alia, Pete Seeger 4 and Utah Phillips' Associate, Sapir and Frumkin; J.D., 2010, Dean's Fellow, St. John's University School of Law; B.A., 2001, Villanova University. * Dorothy Day Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Labor and Employment Law, St. John's University School of Law; J.S.D., 1987, Yale University; L.L.M., 1982, Yale University; J.D., magna cum laude, 1980, University of Detroit Law School; M.B.A., Labor Relations, 1977, Wayne State University Graduate School of Business; B.A., cum laude, 1973, The Catholic University of America School of Philosophy. -

Michael Gottlieb TV+Corporate Ltg Credits 10-2018

Michael Gottlieb (917) 796-7775 • [email protected] • mgld.com • IATSE USA829/NABET Lighting for Television and Corporate Events NBC Entertainment Specials • Saturday Night Live 1995-2012 • Shang Forbes/Paul Ogata Comedy (SNL Digital Shorts & remotes) Specials (Killer Bunny Entertainment) • Christmas in Rockefeller Plaza • Our Town on Broadway with Paul 2013—Kelly Clarkson, Ariana Grande Newman (PBS Masterpiece Theatre) 2012—Trace Adkins • Puerto Rican Day Parade (WNBC) 2006—Sting, Christina Aguilera 2004—Tony Bennett** Commericals • Last Call with Carson Daly (New York) • Lexus “It’s Your Move After Dark” Live • Late Night with Conan O’Brien • Pepsi ”MacGruber” Superbowl XLIII • DIY’s Today Show Tips • Jet Blue (J. Walter Thompson) • Your Total Health • Stride Gum (J. Walter Thompson) • JB Berns exercise video infomercials NBC Sports • 2004 Athens Olympics (venues)* Corporate Producers • Football Night in America (exteriors) • Jack Morton Worldwide • Sportsdesk • Go! Productions / C2 Creative • Devlinhair Productions NBC News • RJO Group • The Today Show (studio/exteriors) • Drury Design Dynamics • Weekend Today • Dateline Corporate Presentations (partial list) • NBC Nightly News • A&E Networks • GE NBC News Specials • Hewlett-Packard • Decision 2008 • Pizza Hut • Papal Visit 2008 • Astra-Zenica • Democracy Plaza (2004 Elections)** • Bristol-Meyers Squibb • Clinton/Lazio Senatorial Debate • Janssen Pharmacia • Novartis Affiliates and O&Os • Novo Nordisk • WNBC New York (2000-2001) • Accenture • Deloitte Daytime/Talk • Morgan Stanley • -

The Idiot Culture

Reflections of post-WafteriEate journalism. THE IDIOT CULTURE By Carl Bernstein t is now nearly a generation since the drama that old Washington Star. Woodward and I were a couple of began with the Watergate break-in and ended with guys on the Metro desk assigned to cover what at bottom the resignation of Richard Nixon, a fuU twenty years was still a burglary, so we applied the only reportorial in which the American press has been engaged in a techniques we knew. We knocked on a lot of doors, we Istrange frenzy of self-congratulation and defensiveness asked a lot of questions, we spent a lot of time listening: about its performance in that afiair and afterward. The the same thing good reporters from Ben Hecht to Mike self<ongratulation is not justified; the defensiveness, Berger tojoe Uebling to the yoimg Tom Wolfe had been alas, is. For increasingly the America rendered today in doing for years. As local reporters, we had no covey of the American media is illusionary and delusionary—<lis- highly placed sources, no sky's-the-Iimit expense figured, unreal, disconnected from the true context of accounts with which to court the powerful at fancy our Uves. In covering actually existing American life, the French restaurants. We did our work far from the media—^weekly, daily, hourly—break new ground in get- enchanting world of tbe rich and the famous and the ting it wrong. The coven^e is distorted by celebrity and powerful. We were grunts. the worship of celebrity; by the reduction of news to gos- So we worked our way up, interviewing clerks, secre- sip, which is the lowest form of news; by sensationalism, taries, administrative assistants.