Romero, Aldemaro, Ruth Baker, Joel E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Users\Usuario\Desktop\TFE

Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Conservatorio Superior de Música de Jaén. Trabajo Fin de Estudios MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE DE TABLAS ................................................................................................ II ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES ........................................................................................... II RESUMEN Y PALABRAS CLAVE .............................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT AND KEYWORDS ................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................... 3 2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN ............................................................................ 4 2.1. Objetivos ......................................................................................................... -

Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0038 Aldemaro Romero Archive Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

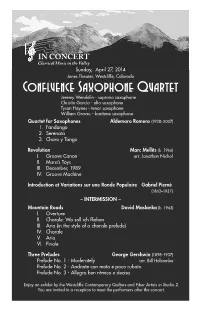

Confluence Saxophone Quartet

IN CONCERT Classical Music in the Valley Sunday, April 27, 2014 Jones Theater, Westcliffe, Colorado Confluence Saxophone Quartet Jeremy Wendelin - soprano saxophone Christin Garcia - alto saxophone Tyson Haynes - tenor saxophone William Graves - baritone saxophone Quartet for Saxophones Aldemaro Romero (1928–2007) 1. Fandango 2. Serenata 3. Choro y Tango Revolution Marc Mellits (b. 1966) I. Groove Canon arr. Jonathan Nichol II. Mara’s Toys III. December, 1989 IV. Groove Machine Introduction et Variations sur une Ronde Populaire Gabriel Pierné (1863–1937) – INTERMISSION – Mountain Roads David Maslanka (b. 1943) I. Overture II. Chorale: Wo soll ich fliehen III. Aria (in the style of a chorale prelude) IV. Chorale V. Aria VI. Finale Three Preludes George Gershwin (1898–1937) Prelude No. 1 - Moderately arr. Bill Holcombe Prelude No. 2 - Andante con moto e poco rubato Prelude No. 3 - Allegro ben ritmico e deciso Enjoy an exhibit by the Westcliffe Contemporary Quilters and Fiber Artists in Studio 2. You are invited to a reception to meet the performers after the concert. PROGRAM NOTES by David Niemeyer You may not be familiar with the name Aldemaro Romero, but you have probably heard his work many times over several decades. He worked with non-classical musicians including Dean Martin, Jerry Lee Lewis, Stan Kenton, and Tito Puente. In addition, Romero was a classical musician who was a guest conductor for the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Orchestra, and the Royal Phil- harmonic Orchestra, and he founded the Caracas Philharmonic Orchestra. As a composer, Romero stuck to his Venezuelan roots, as evidenced by the Quartet for Saxophones. -

Weissman Was My Destination

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 2018 Weissman Was My Destination Aldemaro Romero Jr. CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/226 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Weissman Was My Destination Aldemaro Romero Jr. “The moments of happiness we enjoy take us by surprise. It is not that we seize them, but that they seize us.” Ashley Montagu, British-American anthropologist The date was Monday, August 8, 2016. The coeditor of this book, Gary Hentzi, and I visited Baruch College’s archives to get an idea of the kind of photographic resources we would have available to use as illustrations. We were impressed by how much material the archives contained and by how well organized they were. The director of the archives, Sandra Roff, and her staff walked us through the collection and occasionally showed us a particular picture that they thought could be of interest. “Here’s one you might find curious,” she said. “This is the building that used to be where the Vertical Campus is today.” And when she mentioned the name of the original owner of the building I got goosebumps. “Too good to be true!” I said to myself. I My father and I in Riverside Park in 1953 felt I needed to check the facts. -

A Glimpse Into Quiroga's Musical Roots

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 2017 A Glimpse into Quiroga’s Musical Roots Aldemaro Romero Jr. CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/208 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Glimpse into Quiroga’s Musical Roots sometimes it’s painting. It’s pretty demanding, and Dr. Aldemaro Romero Jr. composition is something that you really have to devote to.” College Talk Selene also knows that that demands on a performer can be pretty daunting when compared “At the music conservatory, I was told that with those of a composer. “I probably feel more popular music is not music, and that’s one of the pressure as a classical pianist than as a composer. things that connected me with your dad, Aldemaro As a composer, I always feel very free, so thank Romero. He could do classical, Bolero, so I God, I don’t have that fear and that anxiety over felt connected because I felt ‘there’s someone my shoulders. I fear more when it comes to being a who had the same problem that I did.’ I felt like classical pianist, but not with composing. Probably classical music is, of course, beautiful, but I needed because I haven’t been composing with very something else.” classical structures. But the academic work I’ve That is how Selene Quiroga, an artist recently composed, I haven’t been putting that pressure invited to Baruch College, explains why she crosses on myself. -

NOAA Tech Rep

NOAA Technical Report NMFS 151 A Technical Report of the Fishery Bulletin Cetaceans of Venezuela: Their Distribution and Conservation Status Aldemaro Romero A. Ignacio Agudo Steven M. Green Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara January 2001 U.S. Department of Commerce Seattle, Washington 1 Abstract.–Sighting, stranding, and cap Cetaceans of Venezuela: Their Distribution and ture records of whales and dolphins for Venezuela were assembled and analyzed Conservation Status to document the Venezuelan cetacean fauna and its distribution in the eastern Caribbean. An attempt was made to con Aldemaro Romero firm species identification for each of the Macalester College records, yielding 443 that encompass 21 Environmental Studies Program and Department of Biology species of cetaceans now confirmed to 1600 Grand Ave. occur in Venezuelan marine, estuarine, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55105-1899 and freshwater habitats. For each species, E-mail address: [email protected] we report its global and local distribu tion, conservation status and threats, and the common names used, along with our A. Ignacio Agudo proposal for a Spanish common name. Fundacetacea, Fundación Sudamericana Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni) is the “Saida Josefina Blondell de Agudo” most commonly reported mysticete. The para la Conservación de Mamíferos Acuáticos long-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus P. O. Box 010, 88010-970 capensis) is the most frequent of the odon Florianópolis, Santa Catarina-SC, Brazil tocetes in marine waters. The boto or tonina (Inia geoffrensis) was found to be ubiquitous in the Orinoco watershed. The Steven M. Green distribution of marine records is consis Department of Biology tent with the pattern of productivity of University of Miami Venezuelan marine waters, i.e., a concen P.O. -

Helix Concert Programme

Innovative Concerts Inspiring Directors Exceptional Musicians Musical Director Clare Bhabra Saturday 15th July 2017 Clare Bhabra studied Music at Birmingham University and then at the Royal Northern College of Music under the guidance of Lydia Mordkovitch. Whilst still studying there she joined Opera North where she enjoyed ten very happy years wallowing in the beautiful music of Opera! She also found time within a busy schedule to become a founder member of the Mirage String Quartet and the Janacek Piano Trio. Now living in Nottingham, Clare continues to perform as both an orchestral and chamber musician including Sinfonia Viva with whom, as well as giving concerts, she is a regular contributor to their outreach education team. In 2010 she was appointed leader of the Nottingham Philharmonic Orchestra and recently performed the Lark ascending with them at the Royal Concert Hall. In 2012 she was invited to join the Tedesca string quartet. As well as performing all over the country they have recently been invited to become quartet in residence for the Midland Sinfonia and directors of regular courses at Benslow Music School. In her spare time you will find her watching cricket or waiting for her bread to rise! Wagner: Siegfried Idyll Finzi: Romance Raff: Sinfonietta in F major Op. 188 ########## Clive Pollard: Southwell Suite Romero: Fuga con Pajarillo Malcolm Arnold: Sinfonietta No 1. Op 48 Siegfried Idyll Richard Wagner (1830-1883) In most books about chamber music, Wagner appears, in some cases somewhat dismissively, as a reference point and influence on others, rather than a subject of study. Siegfried Idyll was written to be played on Christmas day 1870 in the most domestic of situations, to give his waking wife a joint 33rd birthday and Christmas present in gratitude for their baby who shared the opera hero’s name and it was performed on the stairs of their home. -

Aldemaro Romero Jr

Aldemaro Romero Jr. Curriculum Vitae Effective: June 2013 Areas of Expertise Higher Education and Not-for-Profit Administration. Promotion of Higher Education. Innovation and Creativity in Higher Education. Fundraising. Public Outreach. Strategic Planning. Internationalization and Diversification. Teaching and Research. Academic Fields Integrative Biology. Environmental Studies. Marine Mammalogy. Biospeleology. History and Philosophy of Science. Science Communication. Academic Address Dr. Aldemaro Romero Jr., Dean College of Arts and Sciences Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Edwardsville, Illinois 62026-1608, USA [email protected] Telephone: 618 650-5044 Facsimile: 618 650-5050 Personal Address Aldemaro Romero Jr. 2509 Gecko Dr. Maryville, IL 62062 [email protected] Cell phone: 870 761-9465 Current Position Dean and Professor of Biological Sciences Universities Attended University Location, Dates Degree Universidad de Oriente Cumaná, Venezuela 1/70-6/70 Universitat de Barcelona Barcelona, Spain Licenciado Biología 9/70-6/77 University of Miami Coral Gables, FL Ph.D. Biology 1/81-8/84 Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA Certificate, 11/87-12/87 Management for Managers in Natural Resources 2 University and Administrative Experience 2009–Present: Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE) and Professor of Biological Sciences Responsibilities and Accomplishments: • Responsible for 19 departments and 85 areas of study, which include more than 330 full-time faculty/instructors -

CURRICULUM VITAE (Effective: February 2009)

CURRICULUM VITAE (Effective: February 2009) Name Aldemaro Romero Academic Fields Integrative Biology, Environmental Studies. Academic Address Department of Biological Sciences Arkansas State University P.O. Box 599 State University, AR 72467, USA [email protected] Ph.: (870) 972-3082 Fax: (870) 972-2638 Current Position Chair and Professor Universities Attended University Location, Dates Degree Universidad de Oriente Cumaná, Venezuela 1/70-6/70 Universidad de Barcelona Barcelona, Spain Licenciado Biología 9/70-6/77 University of Miami Coral Gables, FL Ph. D. 1/81-8/84 Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA Certificate, 11/87-12/87 Management for Managers in Natural Resources University and Administrative Experience 2003 – Present: Chair and Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR. 1998-2003: Associate Professor and Director of the Environmental Studies Program, Macalester College, St. Paul, MN. 1996-1998: Assistant Professor of Biology, Florida Atlantic University, Davie, FL. 1994-1996: Adjunct (Research) Associate Professor, University of Miami, FL. 1986-1994: Executive Director and CEO, BIOMA, The Venezuelan Foundation for the Conservation of Biodiversity, Caracas, Venezuela. 1985-1986: Country Program Director, The Nature Conservancy, Washington, D.C. 2 Grants, University Scholarships, Fellowships, and Prizes A) Research Grants: 1981 - Peter Nikolic Fellowship in Animal Behavior and Charles Tobach Fund award. Amount: $330. Project Title: The evolution of behavior in surface (eyed), cave (blind), and intermediate forms of Astyanax mexicanus (Pisces: Characidae). 1982 - Organization for Tropical Studies post-course award. Amount: $1,500. Project Title: Genetic basis of behavior and phenotypic variability in Astyanax fasciatus (Cuvier) (Pisces: Characidae) in different environments of Costa Rica. -

Strengthening Friendly Relations

4 The Japan Times Saturday, July 5, 2014 Venezuela national day Strengthening friendly relations Growing ties in energy sector, Working for mutual benefit expanding bonds in other areas Toshihiro nikai Ministry of Economy, trade ChairmAn of the JApAn- and Industry of Japan and the Seiko Ishikawa democracy has grown the most Takeo Hiranuma venezuelA frIendship Council People’s Ministry for Energy Ambassador of venezuelA since 1995, standing first in the ChairmAn of the JApAn-venezuelAn Parliamentary frIendship and Petroleum of the Bolivar- region, with 93 percent polled leAgue as Chairman of the Japan- ian Republic of Venezuela, to On the happy occasion of the answering “agree” or “very Venezuela Friendship Coun- which I had the opportunity to 203rd Anniversary of the Inde- much agree” with the state- venezuela today marks the 203rd Anniversary of the cil, I would like subscribe in March 2009, was pendence of the Bolivarian Re- ment, “democracy might have proclamation of its Independence and I would like to ex- to extend my the first agreement on energy public of problems but it is the best gov- press my deepest congratulations to the warmest con- development between Japan Venezuela, I ernment system.” Also, Vene- government and people of the bolivarian gratulations to and a South American coun- am honored to zuela was ranked second when republic of venezuela on this remarkable the govern- try. It opened a channel of convey the re- people were asked if they be- date as an independent and sovereign ment and peo- communication to diversify newed com- lieved income distribution is country. -

1 R a Brief History of Cave Biology

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-53553-3 - Cave Biology: Life in Darkness Aldemaro Romero Excerpt More information 1 r A brief history of cave biology Some specialist books include a short introduction or brief chronology of the major historical events related to the branch of knowledge they cover. In this book there is an entire chapter on the history of biospele- ological ideas. This is because it is essential to explain why biospeleology as a science in general, and our understanding of cave biology in partic- ular, lags so far behind in mainstream organismal biology, particularly in terms of evolution and ecology. In fact, the author argues that this is so because many biospeleologists have failed to understand the histori- cal framework in which this science has developed. This has led many to uncritically accept both concepts and lexicons that are inconsistent with current biological thought. Thus, this chapter provides a historical explanation of the ideological framework surrounding the majority of biospeleological research. This chapter also contains a number of illus- trations (Figs. 1.1–1.5) related to the historical narrative presented here; more illustrations on this topic may be found in Romero (2001b). 1.1 Conceptual issues An understanding of the history of any particular area of scientific inquiry is essential in order to really appreciate the significance of current knowledge and the voids that need to be filled. Most scientists are not particularly interested in pursuing such a task because the history of science is influenced by philosophy, politics, religion, and other expres- sions of human activities whose comprehension requires interdisciplinary approaches that go beyond what scientists have been normally trained for in universities. -

El Jazz En Venezuela: Trayectoria, Presencia Y Proyección

Cifra Nueva, Trujillo, 7, Enero-Junio 98 El Jazz en Venezuela: Trayectoria, Presencia y Proyección Pancho Crespo Quintero ... Jazz es tocar lo que uno siente (Jo Jones Baterista norteamericano) El día del nacimiento del Jazz fue el día del nacimiento de América. (Manuel Barrios Saxofonista Venezolano) Entre algunos otros, dos hechos han significado un impulso de primer orden para el desarrollo y estado actual de la propuesta jazzística venezolana: la creación del Sistema de Orquestas Juveniles y los estudios musicales en universidades extranjeras. Desde los años 80 gran cantidad de jóvenes músicos iniciaron su formación en estas instituciones, y los resultados comienzan a verse en la presente década. Venezuela se ha convertido en el país con el movimiento jazzístico emergente más sólido del Subcontinente, aseveración que nos permitimos hacer por lo siguiente: un número muy significativo de músicos de gran calidad; una búsqueda consciente y seria de un sonido propio que está abriendo un camino infinito, donde se junta la experiencia de músicos de considerable oficio, con una cantidad impresionante de músicos de nuevas generaciones (en el país y en el exterior, sólo en el Colegio de Música de la Universidad de Berklee*, Bostón, hay A los fines de este trabajo, es importante señalar que el Colegio de Música de Berklee es una tradicional institución dedicada a la enseñanza del jazz. Cifra Nueva • 69 Pancho Crespo Quintero actualmente más de treinta venezolanos, y haciendo carrera profesional en Estados Unidos y en Europa no menos quince). Por último, Venezuela es, desde el año 95 hasta hoy, el país que anualmente edita mayor cantidad de discos de Jazz (producción nacional) en Latinoamérica.