1 R a Brief History of Cave Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Users\Usuario\Desktop\TFE

Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Título Superior de Música. Especialidad Interpretación (Violonchelo) Trabajo Fin de Estudios PROPUESTA INTERPRETATIVA DE LA OBRA SUITE FOR CELLO AND PIANO DE ALDEMARO ROMERO ALUMNO: MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL MODALIDAD A: Trabajo teórico-práctico de carácter profesional TUTORA: Mª NATIVIDAD ÁLVAREZ-OSSORIO TORRES CURSO 2017-2018 Jaén, Junio 2018 Conservatorio Superior de Música de Jaén. Trabajo Fin de Estudios MARIO HIDALGO BERROCAL ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE DE TABLAS ................................................................................................ II ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES ........................................................................................... II RESUMEN Y PALABRAS CLAVE .............................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT AND KEYWORDS ................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................... 3 2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN ............................................................................ 4 2.1. Objetivos ......................................................................................................... -

Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Aldemaro Romero Archive (ASM0038) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0038 Aldemaro Romero Archive Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

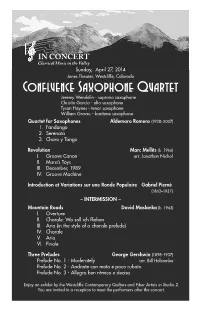

Confluence Saxophone Quartet

IN CONCERT Classical Music in the Valley Sunday, April 27, 2014 Jones Theater, Westcliffe, Colorado Confluence Saxophone Quartet Jeremy Wendelin - soprano saxophone Christin Garcia - alto saxophone Tyson Haynes - tenor saxophone William Graves - baritone saxophone Quartet for Saxophones Aldemaro Romero (1928–2007) 1. Fandango 2. Serenata 3. Choro y Tango Revolution Marc Mellits (b. 1966) I. Groove Canon arr. Jonathan Nichol II. Mara’s Toys III. December, 1989 IV. Groove Machine Introduction et Variations sur une Ronde Populaire Gabriel Pierné (1863–1937) – INTERMISSION – Mountain Roads David Maslanka (b. 1943) I. Overture II. Chorale: Wo soll ich fliehen III. Aria (in the style of a chorale prelude) IV. Chorale V. Aria VI. Finale Three Preludes George Gershwin (1898–1937) Prelude No. 1 - Moderately arr. Bill Holcombe Prelude No. 2 - Andante con moto e poco rubato Prelude No. 3 - Allegro ben ritmico e deciso Enjoy an exhibit by the Westcliffe Contemporary Quilters and Fiber Artists in Studio 2. You are invited to a reception to meet the performers after the concert. PROGRAM NOTES by David Niemeyer You may not be familiar with the name Aldemaro Romero, but you have probably heard his work many times over several decades. He worked with non-classical musicians including Dean Martin, Jerry Lee Lewis, Stan Kenton, and Tito Puente. In addition, Romero was a classical musician who was a guest conductor for the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Orchestra, and the Royal Phil- harmonic Orchestra, and he founded the Caracas Philharmonic Orchestra. As a composer, Romero stuck to his Venezuelan roots, as evidenced by the Quartet for Saxophones. -

Evolution of the Nitric Oxide Synthase Family in Vertebrates and Novel

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.14.448362; this version posted June 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Evolution of the nitric oxide synthase family in vertebrates 2 and novel insights in gill development 3 4 Giovanni Annona1, Iori Sato2, Juan Pascual-Anaya3,†, Ingo Braasch4, Randal Voss5, 5 Jan Stundl6,7,8, Vladimir Soukup6, Shigeru Kuratani2,3, 6 John H. Postlethwait9, Salvatore D’Aniello1,* 7 8 1 Biology and Evolution of Marine Organisms, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, 80121, 9 Napoli, Italy 10 2 Laboratory for Evolutionary Morphology, RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics 11 Research (BDR), Kobe, 650-0047, Japan 12 3 Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR), 2-2- 13 3 Minatojima-minami, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Hyogo, 650-0047, Japan 14 4 Department of Integrative Biology and Program in Ecology, Evolution & Behavior (EEB), 15 Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 16 5 Department of Neuroscience, Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center, and 17 Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA 18 6 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech 19 Republic 20 7 Division of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 21 Pasadena, CA, USA 22 8 South Bohemian Research Center of Aquaculture and Biodiversity of Hydrocenoses, 23 Faculty of Fisheries and Protection of Waters, University of South Bohemia in Ceske 24 Budejovice, Vodnany, Czech Republic 25 9 Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA 26 † Present address: Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of 27 Málaga; and Andalusian Centre for Nanomedicine and Biotechnology (BIONAND), 28 Málaga, Spain 29 30 * Correspondence: [email protected] 31 32 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.14.448362; this version posted June 14, 2021. -

Genetic Variants Vetted by Natural Selection

GENETICS | THE 2015 GSA HONORS AND AWARDS “Wrecks of Ancient Life”: Genetic Variants Vetted by Natural Selection John H. Postlethwait Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5476-2137 (J.H.P.) HE Genetics Society of America’s George W. Beadle Award honors individuals who have made outstanding contributions T to the community of genetics researchers and who exemplify the qualities of its namesake as a respected academic, administrator, and public servant. The 2015 recipient is John Postlethwait. He has made groundbreaking contributions in developing the zebrafish as a molecular genetic model and in understanding the evolution of new gene functions in vertebrates. He built the first zebrafish genetic map and showed that its genome, along with that of distantly related teleost fish, had been duplicated. Postlethwait played an integral role in the zebrafish genome-sequencing project and elucidated the genomic organization of several fish species. Postlethwait is also honored for his active involvement with the zebrafish community, advocacy for zebrafish as a model system, and commitment to driving the field forward. Genetics blossomed as a science spurred by wise selections important genetic variants that can shed light on the mech- of compliant organisms. One hundred years ago, the first anisms of development and physiology in the wild (Albertson paper in the first issue of GENETICS used genetic maps and et al. 2009). Phenotypes exhibited by these “wrecks of ancient chromosome anomalies in Drosophila melanogaster to support life” would be disease states in related species, but in par- the chromosomal theory of inheritance (Bridges 1916). -

Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) En La Cuenca Del Mediterráneo Occidental

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS TESIS DOCTORAL Filogenia, filogeografía y evolución de Luciobarbus Heckel, 1843 (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) en la cuenca del Mediterráneo occidental MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Miriam Casal López Director Ignacio Doadrio Villarejo Madrid, 2017 © Miriam Casal López, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas Departamento de Zoología y Antropología física Phylogeny, phylogeography and evolution of Luciobarbus Heckel, 1843, in the western Mediterranean Memoria presentada para optar al grado de Doctor por Miriam Casal López Bajo la dirección del Doctor Ignacio Doadrio Villarejo Madrid - Febrero 2017 Ignacio Doadrio Villarejo, Científico Titular del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – CSIC CERTIFICAN: Luciobarbus Que la presente memoria titulada ”Phylogeny, phylogeography and evolution of Heckel, 1843, in the western Mediterranean” que para optar al grado de Doctor presenta Miriam Casal López, ha sido realizada bajo mi dirección en el Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – CSIC (Madrid). Esta memoria está además adscrita académicamente al Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física de la Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Considerando que representa trabajo suficiente para constituir una Tesis Doctoral, autorizamos su presentación. Y para que así conste, firmamos el presente certificado, El director: Ignacio Doadrio Villarejo El doctorando: Miriam Casal López En Madrid, a XX de Febrero de 2017 El trabajo de esta Tesis Doctoral ha podido llevarse a cabo con la financiación de los proyectos del Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Además, Miriam Casal López ha contado con una beca del Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. -

The Genome 10K Project: a Way Forward

The Genome 10K Project: A Way Forward Klaus-Peter Koepfli,1 Benedict Paten,2 the Genome 10K Community of Scientists,Ã and Stephen J. O’Brien1,3 1Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, St. Petersburg State University, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russian Federation; email: [email protected] 2Department of Biomolecular Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 3Oceanographic Center, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33004 Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015. 3:57–111 Keywords The Annual Review of Animal Biosciences is online mammal, amphibian, reptile, bird, fish, genome at animal.annualreviews.org This article’sdoi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev-animal-090414-014900 The Genome 10K Project was established in 2009 by a consortium of Copyright © 2015 by Annual Reviews. biologists and genome scientists determined to facilitate the sequencing All rights reserved and analysis of the complete genomes of10,000vertebratespecies.Since Access provided by Rockefeller University on 01/10/18. For personal use only. ÃContributing authors and affiliations are listed then the number of selected and initiated species has risen from ∼26 Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015.3:57-111. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org at the end of the article. An unabridged list of G10KCOS is available at the Genome 10K website: to 277 sequenced or ongoing with funding, an approximately tenfold http://genome10k.org. increase in five years. Here we summarize the advances and commit- ments that have occurred by mid-2014 and outline the achievements and present challenges of reaching the 10,000-species goal. We summarize the status of known vertebrate genome projects, recommend standards for pronouncing a genome as sequenced or completed, and provide our present and futurevision of the landscape of Genome 10K. -

Weissman Was My Destination

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 2018 Weissman Was My Destination Aldemaro Romero Jr. CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/226 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Weissman Was My Destination Aldemaro Romero Jr. “The moments of happiness we enjoy take us by surprise. It is not that we seize them, but that they seize us.” Ashley Montagu, British-American anthropologist The date was Monday, August 8, 2016. The coeditor of this book, Gary Hentzi, and I visited Baruch College’s archives to get an idea of the kind of photographic resources we would have available to use as illustrations. We were impressed by how much material the archives contained and by how well organized they were. The director of the archives, Sandra Roff, and her staff walked us through the collection and occasionally showed us a particular picture that they thought could be of interest. “Here’s one you might find curious,” she said. “This is the building that used to be where the Vertical Campus is today.” And when she mentioned the name of the original owner of the building I got goosebumps. “Too good to be true!” I said to myself. I My father and I in Riverside Park in 1953 felt I needed to check the facts. -

A Glimpse Into Quiroga's Musical Roots

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 2017 A Glimpse into Quiroga’s Musical Roots Aldemaro Romero Jr. CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/208 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Glimpse into Quiroga’s Musical Roots sometimes it’s painting. It’s pretty demanding, and Dr. Aldemaro Romero Jr. composition is something that you really have to devote to.” College Talk Selene also knows that that demands on a performer can be pretty daunting when compared “At the music conservatory, I was told that with those of a composer. “I probably feel more popular music is not music, and that’s one of the pressure as a classical pianist than as a composer. things that connected me with your dad, Aldemaro As a composer, I always feel very free, so thank Romero. He could do classical, Bolero, so I God, I don’t have that fear and that anxiety over felt connected because I felt ‘there’s someone my shoulders. I fear more when it comes to being a who had the same problem that I did.’ I felt like classical pianist, but not with composing. Probably classical music is, of course, beautiful, but I needed because I haven’t been composing with very something else.” classical structures. But the academic work I’ve That is how Selene Quiroga, an artist recently composed, I haven’t been putting that pressure invited to Baruch College, explains why she crosses on myself. -

Construction of a Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly for Genome-Wide

Yin et al. Zool. Res. 2021, 42(3): 262−266 https://doi.org/10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.321 Letter to the editor Open Access Construction of a chromosome-level genome assembly for genome-wide identification of growth-related quantitative trait loci in Sinocyclocheilus grahami (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae) The Dianchi golden-line barbel, Sinocyclocheilus grahami (Zhao et al., 2013). However, the S. grahami population has (Regan, 1904), is one of the “Four Famous Fishes” of Yunnan declined sharply since the 1960s due to habitat damage, Province, China. Given its economic value, this species has water pollution, and alien species invasion (Yang et al., 2007). been artificially bred successfully since 2007, with a nationally As such, it was listed as an animal of Second-Class National selected breed (“S. grahami, Bayou No. 1”) certified in 2018. Protection in 1989, and as an endangered fish in the “China For the future utilization of this species, its growth rate, Red Book of Endangered Animals” in 1998 (Le & Chen, 1998). disease resistance, and wild adaptability need to be improved, Since 2007, our team has successfully achieved the artificial which could be achieved with the help of molecular marker- breeding of S. grahami (Yang et al., 2007), which has not only assisted selection (MAS). In the current study, we constructed helped in avoiding its wild extinction, but also opened a new the first chromosome-level genome of S. grahami, assembled era for its utilization. Moreover, after four generations of 48 pseudo-chromosomes, and obtained a genome size of artificial selection, a new national breed (“S. -

The Sinocyclocheilus Cavefish Genome Provides Insights Into Cave

Yang et al. BMC Biology (2016) 14:1 DOI 10.1186/s12915-015-0223-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The Sinocyclocheilus cavefish genome provides insights into cave adaptation Junxing Yang1*†, Xiaoli Chen2†, Jie Bai2,3,4†, Dongming Fang2,6†, Ying Qiu2,3,5†, Wansheng Jiang1†, Hui Yuan2, Chao Bian2,3, Jiang Lu2,7, Shiyang He2,7, Xiaofu Pan1, Yaolei Zhang2,8, Xiaoai Wang1, Xinxin You2,3, Yongsi Wang2, Ying Sun2,5, Danqing Mao2, Yong Liu2, Guangyi Fan2, He Zhang2, Xiaoyong Chen1, Xinhui Zhang2,3, Lanping Zheng1, Jintu Wang2, Le Cheng5,9, Jieming Chen2,3, Zhiqiang Ruan2,3, Jia Li2,3,7, Hui Yu2,3,7, Chao Peng2,3, Xingyu Ma10,11, Junmin Xu10,11, You He12, Zhengfeng Xu13, Pao Xu14, Jian Wang2,15, Huanming Yang2,15, Jun Wang2,16, Tony Whitten4*, Xun Xu2* and Qiong Shi2,3,10,11* Abstract Background: An emerging cavefish model, the cyprinid genus Sinocyclocheilus, is endemic to the massive southwestern karst area adjacent to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China. In order to understand whether orogeny influenced the evolution of these species, and how genomes change under isolation, especially in subterranean habitats, we performed whole-genome sequencing and comparative analyses of three species in this genus, S. grahami, S. rhinocerous and S. anshuiensis. These species are surface-dwelling, semi-cave-dwelling and cave-restricted, respectively. Results: The assembled genome sizes of S. grahami, S. rhinocerous and S. anshuiensis are 1.75 Gb, 1.73 Gb and 1.68 Gb, respectively. Divergence time and population history analyses of these species reveal that their speciation and population dynamics are correlated with the different stages of uplifting of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. -

Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of the AIG Family in Vertebrates

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Communication Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of the AIG Family in Vertebrates Yuqi Huang 1,†, Minghao Sun 2,† , Lenan Zhuang 2,* and Jin He 1,* 1 Department of Animal Science, College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Veterinary Medicine, College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (J.H.); Tel.: +86-15-8361-28207 (L.Z.); +86-17-6818-74822 (J.H.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Androgen-inducible genes (AIGs), which can be regulated by androgen level, constitute a group of genes characterized by the presence of the AIG/FAR-17a domain in its protein sequence. Previous studies on AIGs demonstrated that one member of the gene family, AIG1, is involved in many biological processes in cancer cell lines and that ADTRP is associated with cardiovascular diseases. It has been shown that the numbers of AIG paralogs in humans, mice, and zebrafish are 2, 2, and 3, respectively, indicating possible gene duplication events during vertebrate evolution. Therefore, classifying subgroups of AIGs and identifying the homologs of each AIG member are important to characterize this novel gene family further. In this study, vertebrate AIGs were phyloge- netically grouped into three major clades, ADTRP, AIG1, and AIG-L, with AIG-L also evident in an outgroup consisting of invertebrsate species. In this case, AIG-L, as the ancestral AIG, gave rise to ADTRP and AIG1 after two rounds of whole-genome duplications during vertebrate evolution.