The Case of Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice SI 128A of 1997 the Zimbabwe Export Processing Zones

Export Processing Zones (Declaration of Export Processing Zones) Notice SI 128A of 1997 The Zimbabwe Export Processing Zones Authority hereby, in terms of section 20 of the Export Processing Zones Act [Chapter 14:07], and after consultation with the Minister responsible for Industry and Commerce and the Minister responsible for Finance makes the following notice:- 1. This notice may be cited as the Export Processing Zones (Declaration of Export Processing Zones). 2. The areas and premises of the companies specified in the first column of the Schedule are declared by the Authority to be export processing zones to the extent defined in the second column.. Schedule 2 (Section 2) EXPORT PROCESSING ZONES S.I. No Notice, Date, Name of Companies, areas or premises, and Definition of premises 128A/97,1,06.06.97,Ollabery Investments (Pvt) Ltd, Lot 5, Arlington Estate, Harare, measuring 110 hectares; 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, IDC Ventersburg Estate, The remaining estate of Ventersburg Estate, Harare, measuring 304,67 acres; 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Manyame Development Corporation, An area measuring 220 hectares west of Harare International Airport ; 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Unsburn Enterprises (Pvt) Ltd Stand Nos. 5748-5806, Mutare Township, Raheen Industrial Park; 128A/97,1,06.06.97, Shagelok Chemicals (Pvt) Ltd Stand NO. 2540, Owl Mine Road, Kadoma, measuring 1,6 hectares; 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Fresca Holdings (Pv t) Ltd, Lot 5A, Cotbank, Shamwari Road, Stapleford, measuring 9300 square metres; 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Wayfield Investments (Pvt) Ltd, Stand Nos. 229 and 230, Galloway Road, Industrial Sites, Norton, measuring 3,910 8 hectares 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, JPS World of Lighting Willowvale Industrial Centre, Units 10, 11 and 12, corner Gleneagles and Bagenham Road, Harare, measuring 1 400 square metres 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Kanyururahove Trading (Pvt) Ltd, Golden Vale Farm in Chinhoyi, measuring 1 010 square metres 128A/97,1, 06.06.97, Zip Plastic Bags (Pvt) Ltd, Stand No. -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland Central Karanda Chimandau Guruve MukosaMukosa Guruve Kamusasa Karanda Marymount Matsvitsi Marymount Mary Mount Locations ShinjeShinje Horseshoe Nyamahobobo Ruyamuro RUSHINGA CentenaryDavid Nelson Nyamatikiti Nyamatikiti Province Capital Nyakapupu M a z o w e CENTENARY Mazowe St. Pius MOUNT DARWIN 2 Chipuriro Mount DarwinZRP NyanzouNyanzou Mt Darwin Chidikamwedzi Town 17 GoromonziNyahuku Tsakare GURUVE Jingamvura MAKONDE Kafura Nyamhondoro Place of Local Importance Bepura 40 Kafura Mugarakamwe Mudindo Nyamanyora Chingamuka Bure Katanya Nyamanyora Bare Chihuri Dindi ARDA Sisi Manga Dindi Goora Mission M u s e n g e z i Nyakasoro KondoKondo Zvomanyanga Goora Wa l t o n Chinehasha Madziwa Chitsungo Mine Silverside Donje Madombwe Mutepatepa Nyamaruro C o w l e y Chistungo Chisvo DenderaDendera Nyamapanda Birkdale Chimukoko Nyamapanda Chindunduma 13 Mukodzongi UMFURUDZI SAFARI AREA Madziwa Chiunye KotwaKotwa 16 Chiunye Shinga Health Facility Nyakudya UZUMBA MARAMBA PFUNGWE Shinga Kotwa Nyakudya Bradley Institute Borera Kapotesa Shopo ChakondaTakawira MvurwiMvurwi Makope Raffingora Jester H y d e Maramba Ayrshire Madziwa Raffingora Mvurwi Farm Health Scheme Nyamaropa MUDZI Kasimbwi Masarakufa Boundaries Rusununguko Madziva Mine Madziwa Vanad R u y a Madziwa Masarakufa Shutu Nyamukoho P e m b i Nzvimbo M u f u r u d z i Madziva Teacher's College Vanad Nzvimbo Chidembo SHAMVA Masenda National Boundary Feock MutawatawaMutawatawa Mudzi Rosa Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mutorashanga Madimutsa Chiwarira -

Mashonaland East Province District Population Projections Report

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE DISTRICT POPULATION PROJECTIONS REPORT i Contents ...........................................................................................................................................................i Foreword .........................................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................4 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................................6 1.2 Objectives of the District Population Projections ............................................................6 1.3 Methodology .........................................................................................................................6 1.4 Limitations of the Analysis ...............................................................................................7 2.0 Base Population ...................................................................................................................7 ii List of tables Table 1: Population by sex according to provinces numbers and proportions 1992, 2002 and 2012 .........8 Table 2: Projected Male Population by District Mashonaland East Province 2012-2032...........................9 Table -

ZIMBABWE), Urban Growth in Ruwa (Zimbabwe), 1986-2015

MATSETE KAPA PEHELETSO YA TJHELETE YA DIKHAMPANE TSA PORAEFETE TSA NTSHETSOPELE Published by the UFS YA LEFATSHE LE KGOLO YA http://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/trp TOROPO KA MORA DINAKO TSA © Creative Commons With Attribution (CC-BY) How to cite: Muzorewa, T.T. & Nyandoro, M. 2019. Investment by private land developer companies and postcolonial BOKOLONE RUWA (ZIMBABWE), urban growth in Ruwa (Zimbabwe), 1986-2015. Town and Regional planning, no.74, pp. 51-63. 1986-2015 Atikele ena e lekola ka mokgwa Investment by private land developer companies wa boleng, seabo sa letsete kapa and postcolonial urban growth in Ruwa (Zimbabwe), peheletso ya tjhelete ya dikhampane tsa poraefete tsa ntshetsopele ya lefatshe 1986-2015 ntshetsopeleng ya toropo ya Zimbabwe ka mora dinako tsa bokolone, ka ho qoolla, re itshetlehile toropong ya Ruwa Terence Muzorewa & Mark Nyandoro (Ruwa Town). Toropo ena e teteaneng e tswa pele ka ho kenya batho ba poraefete ba ntshetsang lefatshe pele kgolong le katolosong ya yona. Ditoropo tsohle tse DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp74i1.5 entsweng ka mora nako ya bokolone Revised April 2019, Published 30 June 2019 di ile tsa hlaha ho tswa ho letsete kapa The authors declared no conflict of interest for this title or article peheletsong ya tjhelete ya Mmuso ka tshebediso ya Growth Point Policy. Ka ho bontsha phapang, Ruwa e ne e ikgethile, Abstract ka lebaka la hore e hlahile/thehilwe This article qualitatively analyses the role of private land developer companies’ ka mokgwa wa kopanelo ya setjhaba- investment in postcolonial Zimbabwe’s urban development, with special reference to poraefete (public-private). -

Census Results in Brief

116 Appendix 1a: Census Questionnaire 117 118 119 120 Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe 309 Gokwe North 702 Urban Areas Gokwe South 703 Marondera 321 Gweru Rural 704 Chivhu Town Board 322 Kwekwe Rural 705 Ruwa Local Board 323 Mberengwa 706 MASHONALAND WEST 4 Shurugwi 707 Rural Districts Zvishavane 708 Chegutu 401 Urban Areas Hurungwe 402 Gweru 721 Mhondoro-Ngezi 403 Kwekwe 722 Kariba 404 Redcliff 723 Makonde 405 Zvishavane 724 Gokwe Centre 725 . -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital Hunyani Casembi Key Location Chikafa Chidodo Muzeza Musengezi Mine Mushumbi Musengezi Pools Chadereka Mission Mbire Mukumbura Place of Local Importance Hoya Kaitano Kamutsenzere Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Muzarabani Mavhuradonha Village Bakasa St. St. Gunganyama Pachanza Centenary Alberts Alberts Nembire Road Network Kazunga Chawarura Dotito Primary Chironga Rushinga Mount Rushinga Mukosa Guruve Karanda Rusambo Marymount Chimanda Secondary Marymount Shinje Darwin Rusambo Centenary Nyamatikiti Guruve Feeder azowe MashonalandMount M River Goromonzi Darwin Mudindo Dindi Kafura Bure Nyamanyora Railway Line Central Goora Kondo Madombwe Chistungo Mutepatepa Dendera Nyamapanda International Boundary Madziwa Borera Chiunye Kotwa Nyakudya Shinga Bradley Jester Mvurwi Madziwa Vanad Kasimbwi Institute Masarakufa Nzvimbo Madziwa Province Boundary Feock Mutawatawa Mudzi Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mudzi Mutorashanga Charewa Chikwizo Howard District Boundary Nyota Shamva Nyamatawa Gozi Institute Bindura Chindengu Kawere Muriel Katiyo Rwenya Freda & Mont Dor Caesar Nyamuzuwe River Mazowe Rebecca Uzumba Nyamuzuwe Katsande Makaha River Shamva Mudzonga Makosa Trojan Shamva Nyamakope Fambe Glendale BINDURA MarambaKarimbika Sutton Amandas Uzumba All Nakiwa Kapondoro Concession Manhenga Kanyongo Souls Great Muonwe Mutoko PfungweMuswe Dyke Mushimbo Chimsasa Lake/Waterbody Madamombe Jumbo Bosha Nyadiri Avila Makumbe Mutoko Jumbo Mazowe Makumbe Parirewa Nyawa Rutope Conservation Area -

Cleveland Dam Ramsar Site

Cleveland Dam Ramsar Site Introduction Cleveland Dam is a reservoir located 12.5km from the Harare city centre under the municipal urban district of Greendale in Harare province, Zimbabwe. The Dam is leased to Haka Camp who manages it in collaboration with the City of Harare. It was constructed in 1913 for water supply for the city of Harare. Cleveland Dam covers an area of 2500 hectares and is one of the countries seven Ramsar sites. The Ramsar Convention provides a framework for wetland conservation and asks that nations promote the sustainable utilization and conservation of wetlands. Zimbabwe became a signatory to the convention in 2011. Cleveland Dam has a water capacity of 910 million litres. There are three principal water sources draining into the dam, namely the Mabvuku, Manresa and Chikurubi rivers. The catchment area is a public amenity and vital water source as the water from the Cleveland Dam ultimately flows into Lake Chivero and is distributed to people in Harare, Chitungwiza, Ruwa, and Norton Municipal towns for drinking and other industrial and domestic purposes. Biodiversity Much of the areas to the north and east of the site are covered by miombo woodland. The southern plateau area is being re-afforested through planting of indigenous tree species such as acacia and Azanza garckeana, Julbernardia globiflora, Brachystegia spiciformis and Uapaca kirkiana. A smaller, but sparse woodland lies at the centre of the grassland covering the northern section of the park. The rest of the site (about 1,500 hectares) is woodland grassland Ramsar Criteria - 2,3,4 and grassland. -

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map Kanyemba Mana Lake C. Bassa Pools Legend Province Capital Mashonaland Key Location r ive R Mine zi West Hunyani e Paul V Casembi b Chikafa Chidodo Mission Chirundu m Angwa Muzeza a Bridge Z Musengezi Place of Local Importance Rukomechi Masoka Mushumbi Musengezi Mbire Pools Chadereka Village Marongora St. International Boundary Cecelia Makuti Mashonaland Province Boundary Hurungwe Hoya Kaitano Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Chitindiwa Muzarabani District Boundary Shamrocke Bakasa Central St. St. Vuti Alberts Alberts Nembire KARIBA Kachuta Kazunga Chawarura Road Network Charara Lynx Centenary Dotito Kapiri Mwami Guruve Mount Lake Kariba Dora Shinje Masanga Centenary Darwin Doma Mount Maumbe Guruve Gachegache Darwin Railway Line Chalala Tashinga KAROI Kareshi Magunje Bumi Mudindo Bure River Hills Charles Mhangura Nyamhunga Clack Madadzi Goora Mola Mhangura Madombwe Chanetsa Norah Silverside Mutepatepa Bradley Zvipane Chivakanyama Madziwa Lake/Waterbody Kariba Nyakudya Institute Raffingora Jester Mvurwi Vanad Mujere Kapfunde Mudzumu Nzvimbo Shamva Conservation Area Kapfunde Feock Kasimbwi Madziwa Tengwe Siyakobvu Chidamoyo Muswewenhede Chakonda Msapakaruma Chimusimbe Mutorashanga Howard Other Province Negande Chidamoyo Nyota Zave Institute Zvimba Muriel Bindura Siantula Lions Freda & Mashonaland West Den Caesar Rebecca Rukara Mazowe Shamva Marere Shackleton Trojan Shamva Chete CHINHOYI Sutton Amandas Glendale Alaska Alaska BINDURA Banket Muonwe Map Doc Name: Springbok Great Concession Manhenga Tchoda Golden -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. XCVIII, No. 52 29th MAY, 2020 Price RTGS$20,00 General Notice 898 of 2020. The following documents must accompany your application: CITY OF GWERU (a) Company Profile; Invitation to Competitive Bidding (b) Financial Profile; (c) Organisation Structure including any associates and/or partner firms; TENDERS are invited from registered and reputable companies in terms of the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets (d) Number of years in practice of each partner; Act [Chapter 22:23], and the Public Procurement and Disposal of (e) Dedicated area and core competency; and Public Assets (General) Regulations, 2018 (Statutory Instrument 5 (f) Practising certificates copy. of 2018) for the following goods: State proven experience in provision of personnel where your Tender number company has carried out similar engagements in the past and briefly describe the nature and tasks. Confirm that your company: Has no COG/01/05/2020. Supply and delivery of water treatment on-going litigation with any party; and is not currently suspended chemicals (Chlorine Gas, Aluminium sulphate granular, by the Law Society of Zimbabwe. HTH and Hydrated lime). Closing date: 19th June, 2020. In addition, submit: Certificate of incorporation; Current Tax Submission of tender Clearance Certificate; and three contactable referees. Tender documents can be obtained from City of Gweru All applications must be marked Invitation to Expression of Interest (Procurement Management Unit, Offices 373 and375), Third for Legal Services and must be submitted at City of Gweru (Town loor, o nHo se,dur g ork ghours(0830hours o1 3 rFlTH^dmai w ki h!0830u hm w m t i1630Clerk’so ° Office) not later than 19th June, 2020, before 1000 hours. -

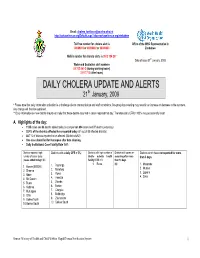

DAILY CHOLERA UPDATE and ALERTS 21Th January, 2009

Email: [email protected] http://ochaonline.un.org/Default.aspx?alias=ochaonline.un.org/zimbabwe Toll free number for cholera alert is Office of the WHO Representative in 08089001 or 08089002 or 08089000 Zimbabwe Mobile number for cholera alerts is 0912 104 257 Date of issue:21th January, 2008 Water and Sanitation alert numbers 04 703 941-2 (during working hours) 2 917 710 (after hours) DAILY CHOLERA UPDATE AND ALERTS 21th January, 2009 * Please note that daily information collection is a challenge due to communication and staff constraints. On-going data cleaning may result in an increase or decrease in the numbers. Any change will then be explained. ** Daily information on new deaths should not imply that these deaths occurred in cases reported that day. Therefore daily CFRs >100% may occasionally result A. Highlights of the day: • 1125 cases and 38 deaths added today (in comparison 894 cases and 37 deaths yesterday) • 53.4% of the districts affected have reported today (31 out of 58 affected districts) • 88.7 % of districts reported to be affected (55 districts/62) • One case denotified for Hurungwe after data cleaning. • Daily Institutional Case Fatality Rate 1.6% Districts reported high Districts with a daily CFR > 5% : Districts with high number of Districts with cases re- Districts which have not reported for more number of cases today deaths outside health occurring after more than 3 days: (cases added today> 30) facility/ CTC > 3 than 14 days 1. Rushinga 1. Ruwa Nil 1. Makumbe 1. Harare (BRIDH) 2. Mutoko 2. Shamva 2. Murehwa 3. -

4.6 Zimbabwe Storage and Milling Company Contact List

4.6 Zimbabwe Storage and Milling Company Contact List Bulawayo Milling Companies Name Phone Number Basic Foods Mr. M. A. Bingepinge Tel:+263(09)484851/3 78 Silver Crescent Kelvin West, Bulawayo Rainbow Foods Mr. M. Zhuwarara Tel:+263(0)772278842 15 Ironbidge Donnington, Bulawayo Ilanga Foods A Chiswa Tel:+263(0)733246582 18 Market Road, Kelvin North National Foods Ltd Mr. Nheta Tel:+263(0)712422112 Multifoods Milling Company Mrs. S. Moyo Tel:+263(0)712607191 Farm 19Holland Ragavin T/A Fatsita Foods F. Moyo Tel:+263(0)772378307 CSC Old Complex Bulateke Milling E Nkala Tel:+263(0)712529520 14640 Kelvin North Zim Milling Company Mr. M. Ratisai Tel:+263(0)712767261 13926 Inotho Road,Kelving North Rd Membar Milling Mr. B. Tshuma Tel:+263(0) 712786569 65 Mpumelelo Rd, Kelvin North Upwell Foods CSC Old Complex W. Makavana Tel:+263(0)772741629 Ivegill Milling E. Ndebele Tel:+263(0)712702513 Old Cold Storage Complex, Crown Foods Farm 19Holland, Bulawayo/Malaba Farm, Woolendale Vusa Sibanda Tel:+263(0)712801441 Memban Milling Company Mr. B. Tshuma Tel:+263(0)405506-8 65 Mpumelelo Rd, Kelvin North Xaba Milling Subdivision G of Portion B, Kensington Farm Mr. J. Xaba Tel:+263(0)712207196 Goldendale Trading Mr. T. Sibanda Tel:+263(0)712766560 17055 Steelarc Road Kelving West LongwalkMillingNowRockForestInvestment CSC Old Complex J. Nkomazana Tel:+263(0)712760020 AdamsMilling15341 Kelvin North Rd T. Tavengwa Tel:+263(0)77739879 ZimbabweMilling M. Ratisai Tel:+263(0)712767261 13926 Inotho Road,Kelving North Rd Socialised Milling Co. Mr. K Sibanda Tel:+263(0)772708661 10 Wingrove Rd, Thorngrove Euroquest Mr. -

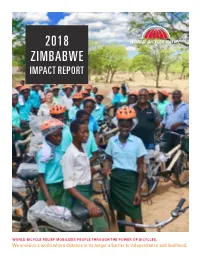

2018 Zimbabwe Impact Report

2018 ZIMBABWE IMPACT REPORT WORLD BICYCLE RELIEF MOBILIZES PEOPLE THROUGH THE POWER OF BICYCLES. We envision a world where distance in no longer a barrier to independence and livelihood. ZIMBABWE COUNTRY PROFILE 17.1M 43.3/Km2 POPULATION1 POPULATION DENSITY1 2 390,757 Km LIVE IN RURAL LIVE IN URBAN 2 2 SURFACE AREA1 68% AREAS 32% COMMUNITIES In areas of Zimbabwe where walking is the primary mode of In areas where distance is a transportation, distance is a challenge to earning a livelihood. challenge, meeting everyday needs is a struggle against time 38% and fatigue. OF RURAL ZIMBABWE LIVES ON LESS THAN 9Km $2 PER DAY3 AVERAGE DISTANCE TO A HEALTHCARE FACILITY7 SCHOOL ENROLLMENT RATE4 89% 49% 88% 48% PRIMARY GIRLS SECONDARY GIRLS PRIMARY BOYS SECONDARY BOYS LIFE EXPECTANCY1 HIV PREVALENCE1 ACCESS TO SAFE WATER1 59 YEARS 14.7% 96% REFERENCES: 1) http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/zimbabwe-population/ 3) https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Zimbabwe_ 2) http://tradingeconomics.com/zimbabwe/rural-population-percent-of-total Health_System_Assessment20101.pdf -population-wbr-data.html 4) https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/zimbabwe_statistics.html http://uis.unesco.org/country/ZW 2018 ZIMBABWE IMPACT REPORT 3 DEAR FRIENDS We at World Bicycle Relief have the honour of being a world-class organization that is paving the way for increased mobility in Zimbabwe. Offering quality products and excellent service, we stand shoulder to shoulder with our global partners. Not everyone has the luxury of riding a bicycle when they really need it. However, when one does it often does the trick to bring one closer to one’s home environment and makes it easier to commit to various tasks, whilst making one healthier and happier.