Summer 2019 Meeting at Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

Cadw Custodian Handbook 2017

Cadw Custodian Handbook 2017 Index 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Opening Statement 1.2 Customer Service 1.3 Providing Information for Public, Press & Visitors 1.4 Social Media 1.5 Controlling Expenditure 1.6 Contact 1.7 New Member of Staff Induction 2.0 Cadw Membership and Group Visits 2.1 Cadw Membership 2.2 Explorer Passes 2.3 Visits By Tour Operators 2.4 Visits By Local Residents and Groups 2.5 Educational Visits & Visits By Overseas Groups to Monuments 2.6 Disabled Visitors 3.0 Dealing With Complaints 3.1 Dealing With Difficult People 3.2 Dealing With Shoplifting 3.3 Lost and Found Property 3.4 Children & Vulnerable Adult Protection Policy 4.0 Reporting Accidents & Potentially Unsafe, Dangerous & Hazardous Locations 4.1 Accident Procedure for Visitors 4.2 Unsafe, Dangerous & Hazardous Locations Procedure 4.3 Attendance at Monuments in Severe Weather Conditions 4.4 Cleanliness and Maintenance of Monuments 4.5 Property of Customers 1 5.0 General Information 5.1 Staff Uniform 5.2 Flag Flying 5.3 The Events Programme 5.4 Private Hire of Monuments 5.5 Licences – Weddings/Music/Alcohol 5.6 Training Record 5.7 Contractors Working On Site 5.8 Dogs and Guide Dogs 6.0 Health & Safety Guidance 6.1 General Health & Safety Information & Risk Assessment Process 6.2 Manual Handling 6.3 Working at Height 6.4 Lone Working 6.5 Fire Safety & Emergency Procedures 6.6 Cleaning & Control of Substances Hazardous to Health 6.7 First Aid 6.8 Office & Equipment Inspection & Testing 6.9 Display Screen Equipment 6.10 Events 6.11 Out of Hours Call Out Procedure 6.12 Health -

Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Managing online communications and feedback relating to the Welsh visitor attraction experience: apathy and inflexibility in tourism marketing practice? David Huw Thomas, BA, PGCE, PGDIP, MPhil Supervised by: Prof Jill Venus, Dr Conny Matera-Rogers and Dr Nicola Palmer Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David. 2018 i ii DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 iii iv Abstract Understanding of what constitutes a tourism experience has been the focus of increasing attention in academic literature in recent years. For tourism businesses operating in an ever more competitive marketplace, identifying and responding to the needs and wants of their customers, and understanding how the product or consumer experience is created is arguably essential. -

Talybont Farm Llawhaden | Narberth | Pembrokeshire | SA67 8HJ Talybont Farmhouse

Talybont Farm Llawhaden | Narberth | Pembrokeshire | SA67 8HJ Talybont Farmhouse “We immediately fell for this house as soon as we stepped through the front door. It offers space and tranquillity. The farmhouse is in a unique, almost fairytale, location with views of the medieval castle and church while the River Cleddau meanders its way through the countryside below,” says Jackie. “We have lived at the property for five years and have refurbished much of the house to ensure it is maintained to a high standard. We have refitted the bathrooms and converted the Aga from oil to electric,” says David. “As well as this we have two large log burners which create an inviting home in the winter months.” “Since moving into the property we have created further accommodation in a disused barn. This was stripped bare and converted into a two bedroom cottage. At the moment we use it for when friends and family come to visit but it could also be used as an annexe, holiday let or to run a business from. The house has a welcoming farmhouse style kitchen and dining room. It is my favourite room with a large inglenook fireplace which is big enough to sit in!” says Jackie. “It is a very comfortable house in the winter and our kitchen is the heart of the home where we spend the majority of our time.” “Our motivation in moving to Llawhaden was to leave the city life and embrace a fully rural way of life. At the farmhouse we have been able to do just that. -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1. -

Autumn / Winter 2013 River Special Area of Conservation (SAC) – Concentrating on the Area from the Source of the Afon Syfynwy to the Dam at Llys Y Frân

Llys y Frân Catchment Project Work began on the Llys y Frân Catchment Pro- ject in July. This new initiative, led by Afonydd Cymru in association with Pembrokeshire Riv- ers Trust, is a trial collaborative partnership with Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water and Natural Re- sources Wales (NRW). The project is based on the Afon Syfynwy catchment, a tributary of the Eastern Cleddau, which drains into the Rosebush and Llys y Frân Volume 10 Issue 3 Reservoirs and lies within the Eastern Cleddau Autumn / Winter 2013 River Special Area of Conservation (SAC) – concentrating on the area from the source of the Afon Syfynwy to the dam at Llys y Frân. In this Issue Llys y Frân Reservoir has been susceptible to Llys y Frân Catchment Blue Green Algae blooms in recent years. The Project project aims to achieve a better understanding Pages 1 & 2 of factors impacting on water quality and nutri- ent loading within the catchment in relation to Hedgehogs in land use, looking at activities such as forestry Pembrokeshire operations, sewage inputs and farming. It is Pages 2 - 4 hoped that this initiative will deliver positive measures to help improve water quality, mini- mise the risk of pollution incidents and help to Habitat for Rare Dragonfly gain favourable conservation status. Saved Pages 4 - 5 Rare Fish Caught in the Haven Pages 5 - 6 Wildlife Trust Supports Local Charcoal Maker Pages 6 - 7 Hang on to your Tackle! Pages 8 - 9 Courses and Events Pages 10 - 11 Contact details Blue Green Algae at Llys y Frân Page12 Photo: Natural Resources Wales Ant Rogers — Biodiversity Implementation Officer [email protected] 01437764551 Page 1 Further information about the project can be obtained by emailing the Catchment Project Officer, Ro Rogers at: [email protected] Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust is always keen to recruit new volunteers. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Solva Proposals Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1

Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority Solva Conservation Area Proposals Supplementary Planning Guidance to the Local Development Plan for the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Adopted 12 October 2011 Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 1 SOLVA CONSERVATION AREA PROPOSALS CONTENTS PAGE NO. FOREWORD . 3 1. Introduction. 5 2. Character Statement Synopsis . 7 3. SWOT Analysis. 14 4. POST Analysis . 18 5. Resources . 21 6. Public Realm . 23 7. Traffic Management. 25 8. Community Projects. 26 9. Awareness . 27 10. Development . 29 11. Control . 30 12. Study & Research. 31 13. Boundaries . 32 14. Next Steps . 34 15. Programme . 35 16. Abbreviations Used . 36 Appendix A: Key to Conservation Area Features Map October 2011 Solva_proposals_Layout 1 18/10/2011 15:03 Page 2 PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK Poppit A 487 Aberteifi Bae Ceredigion Llandudoch Cardigan Cardigan Bay St. Dogmaels AFON TEIFI A 484 Trewyddel Moylegrove Cilgerran A 487 Nanhyfer Nevern Dinas Wdig Eglwyswrw Boncath Pwll Deri Goodwick Trefdraeth Felindre B 4332 Newport Abergwaun Farchog Fishguard Aber-mawr Cwm Gwaun Crosswell Abercastle Llanychaer Gwaun Valley B 4313 Trefin Bryniau Preseli Trevine Mathry Presely Hills Crymych Porthgain A 40 Abereiddy Casmorys Casmael Mynachlog-ddu Castlemorris Croesgoch W Puncheston Llanfyrnach E Treletert S Rosebush A 487 T Letterston E B 4330 R Caerfarchell N C L Maenclochog E Tyddewi D Cas-blaidd Hayscastle DAU Wolfscastle B 4329 B 4313 St Davids Solfach Cross Solva Ambleston Llys-y-fran A 487 Country Park Efailwen Spittal EASTERN CLEDDAU Treffgarne Newgale A 478 Scolton Country Park Llandissilio Llanboidy Roch Camrose Ynys Dewi Ramsey Island Clunderwen Solva Simpson Cross Clarbeston Road Nolton Conservation Area Haverfordwest Llawhaden Druidston Hwlffordd A 40 B 4341 Hendy-Gwyn St. -

Carew/Cresswell Quay Half Day + Walk

carew_cresswellquay:english 21/10/10 16:42 Page 1 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Carew/Cresswell Quay Half Day + Walk SCALE: 0 400 800 m KEY DISTANCE/DURATION: 4.9 miles (7.8 km) 2 hours 30 minutes •••• Circular Route PUBLIC TRANSPORT: Service bus Carew 360/361, Cresswell Quay 361 Public Right of Way CHARACTER: Easy to moderate grade, 1.5 miles (2.5 km) minor road walking, fields and livestock, Car Park stone stiles & steps, some stretches are wet and muddy Public Toilets LOOK OUT FOR: Carew Castle, Tidal Mill and mill ponds • river views • the old quay Bus Stop pretty villages • water fowl COUNTRY CODE! • Enjoy the countryside and respect its life and work • Guard against all risk of fire • Leave gates and property as you find them • Keep your dogs under close control • Keep to public paths across farmland Cresswell • Take your litter home Quay Carew © Crown copyright. All rights reserved Pembrokeshire Coast National Park 100022534, 2004. carew_cresswellquay:english 21/10/10 16:42 Page 2 Carew/Cresswell Quay Half Day + Walk Duration: 2 hours 30 minutes 11th century, making Pembroke Castle their headquarters. However, the Length: 4.9 miles (7.8 km) constable of Pembroke Castle, Gerald Public transport: Service bus de Windsor, chose to build a castle of Carew 360/361, Cresswell Quay his own at Carew. 361. Grid ref: SN043051 The first castle was probably wooden. It was later replaced by a stone structure that was added to over the The branching pattern of the centuries with the final development in Daugleddau and its tributaries are a the 16th century. -

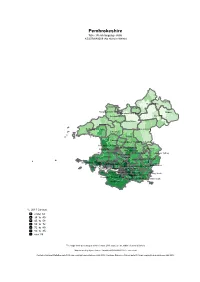

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port Environmental Statement Volume II: Figures

Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port Environmental Statement Volume II: Figures rpsgroup.com Replacement Linkspan, Fishguard Port CONTENTS FIGURES * Denotes Figures embodied within text of relevant ES chapter (Volume I) Figure 2.1: Site Location M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9000 Figure 2.2: Single Tier Linkspan Layout Plan M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-1004 *Figure 2.3: Open Piled Deck, Bankseat and Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.4: Bankseat *Figure 2.5: Landside of Buffer Dolphin and Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.6: Seaward Edge of Buffer Dolphin Showing Forward End of Linkspan Ramp *Figure 2.7: Jack Up Pontoon Figure 2.8: Demolition and site clearance M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9002 Figure 2.9: Linkspan levels M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-3001 *Figure 2.10: Typical Backseat Plan and Section, showing pile arrangement *Figure 2.11: Indicative Double Tiered Linkspan Layout Figure 2.12: Proposed site compound locations M0680-RPS-00-XX-DR-C-9003 *Figure 3.1: Comparison of Alternative Revetment Designs *Figure 4.1: Extent of hydraulic model of Fishguard harbour and its approaches *Figure 4.2: Wave disturbance patterns – 1 in 50 year return period storm from N *Figure 4.3: Significant wave heights and mean wave direction 1 in 50 year return period storm from 120° N *Figure 4.4: Typical tidal flood flow patterns in Fishguard Harbour *Figure 4.5: Typical tidal ebb flow patterns in Fishguard Harbour *Figure 4.6: Tidal levels currents and directions at the linkspan site – spring tide *Figure 4.7: Tidal current speed difference, proposed minus existing, at time of maximum current speed at -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle.