Copyright Law and Pornography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bel Ami Freshmen 2020 Bel Ami

BRUNO GMUENDER Bel Ami Freshmen 2020 Bel Ami This stunning calendar features Bel Ami’s most charming young guys, captured on their way to becoming stunning men. Summary They might be young, but they’re anything but innocent! Here are Bel Ami’s most charming young guys, captured on their way to becoming stunning men. They like each other a lot, and so will you. This calendar features the hottest and freshest new Bel Ami guys. Contributor Bio Bel Ami is a gay film studio with offices in Bratislava, Prague and Budapest. It was established in 1993 by Bruno Gmuender filmmaker George Duroy, a Slovak native who took his pseudonym from the protagonist Georges Duroy in Guy 9783959853699 Pub Date: 7/1/19 de Maupassant's novel Bel Ami. In addition to DVDs, Bel Ami and Bruno Gmünder also produce calendars and $21.99 USD/$28.99 CAD photo books, and its performers are frequent headliners at nightclubs and similar venues around Europe, the United States and elsewhere. 14 Pages Carton Qty: 0 Series: Calendars 2020 16.5 in H | 12 in W Bel Ami Online Boys 2020 Bel Ami This calendar features the freshest Online Boys from Bel Ami's Internet presence BelamiOnline.com, one of the hottest sites on the net. Summary This calendar of the world-famous brand Bel Ami lets hearts beat faster around the globe. You will find the freshest Online Boys faces from their Internet presence BelamiOnline.com, one of the hottest sites on the net. This monthly calendar features the brand’s most successful boys and promising newcomers. -

Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 7 3-15-2011 Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything Alan Wilcox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan Wilcox, Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything, 31 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 1 (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol31/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything By Alan Wilcox* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. ....... 254 II. PAST AND CURRENT RESTRICTIONS ON VIOLENCE IN VIDEO GAMES ........................................... 256 A. The Origins of Video Game Regulation...............256 B. The ESRB ............................. ..... 263 III. RESTRICTIONS IMPOSED IN OTHER COUNTRIES . ............ 275 A. The European Union ............................... 276 1. PEGI.. ................................... 276 2. The United -

Sexercising Our Opinion on Porn: a Virtual Discussion

Psychology & Sexuality ISSN: 1941-9899 (Print) 1941-9902 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpse20 Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion Elly-Jean Nielsen & Mark Kiss To cite this article: Elly-Jean Nielsen & Mark Kiss (2015) Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion, Psychology & Sexuality, 6:1, 118-139, DOI: 10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 Published online: 22 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 130 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpse20 Psychology & Sexuality, 2015 Vol.6,No.1,118–139, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.984518 Sexercising our opinion on porn: a virtual discussion Elly-Jean Nielsen* and Mark Kiss Department of Psychology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada (Received 1 May 2014; accepted 11 July 2014) A variety of pressing questions on the current topics and trends in gay male porno- graphy were sent out to the contributors of this special issue. The answers provided were then collated into a ‘virtual’ discussion. In a brief concluding section, the contributors’ answers are reflected upon holistically in the hopes of shedding light on the changing face of gay male pornography. Keywords: gay male pornography; gay male culture; bareback sex; pornography It is safe to say that gay male pornography has changed. Gone are the brick and mortar adult video stores with wall-to-wall shelves of pornographic DVDs and Blu-rays for rental and sale. -

Copyright Law and the Commoditization of Sex

COPYRIGHT LAW AND THE COMMODITIZATION OF SEX Ann Bartow* I. COPYRIGHT LAW PERFORMS A STRUCTURAL ROLE IN THE COMMODITIZATION OF SEX ............................................................................ 3 A. The Copyrightable Contours of Sex ........................................................ 5 B. Literal Copying is the Primary Basis for Infringement Allegations Brought by Pornographers ................................................ 11 1. Knowing Pornography When One Sees It ...................................... 13 C. Sex Can Be Legally Bought and Sold If It Is Fixed in a Tangible Medium of Expression ........................................................................... 16 II. THE COPYRIGHT ACT AUTHORIZES AND FACILITATES NON- CONTENT-NEUTRAL REGULATION OF EXPRESSIVE SPEECH ........................ 20 III. HARMFUL PORNOGRAPHY IS ―NON-PROGRESSIVE‖ AND ―NON- USEFUL‖ ....................................................................................................... 25 A. Pornography as Cultural Construct ...................................................... 25 B. Toward a Copyright Based Focus on Individual Works of Pornography ......................................................................................... 35 1. Defining and Promoting Progress .................................................. 37 2. Child Pornography ......................................................................... 39 2. Crush Pornography ........................................................................ 42 3. “Revenge Porn” -

Progress in Empirical Research on Children's

Volume XII Number 2, November 1983 ISSN:0091-3995 Sex Information and Education Council of the U.S. PROGRESS IN EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ON CHILDREN’S SEXUALITY Ernest Borneman, PhD President, Austrian Society for Research in Sexology President, German Society for Research in Sociological Sexology [Throughout my years of attending local, regional, national, impossible in most countries of the western world. The result is and international conferences, I have rarely heard a paper that not only ignorance but a plethora of false information. provoked such intense and prolonged discussion as did Dr. When my first research team began its work some 40 years Ernest Borneman’s presentation at the Sixth World Congress of ago, we believed, for instance, that a boy’s first pollution (emis- Sexology he/d in Washington, D.C. in May 7983. For days after sion of semen at times other than during coitus) indicated that his talk, wherever conference participants gathered, someone his semen had become fertile. We believed, too, that a girl would invariably ask; “Did you hear Borneman’s paper!” and could not be impregnated before she had her menarche. We thus trigger engrossed interaction. Both the methodology and accepted these assumptions because they seemed obvious. It the interpretation of his findings prompted heated reaction never occurred to us to question or test them. pro and con. I a/so had the opportunity of using Dr. Borne- Then we heard of a nine-year-old girl who had been raped man’s paper with our New York University international and had borne a child prior to her menarche. -

Rethinking the Liberal Legacy

56 I Allan Janik 72. Gerhard Ostreich has laid the foundations of such a study in the essays collected in Geist und Gestalt desfriihmodernen Staats (Berlin, 1%9) and Strukturprobleme der Neuzeit; ed. G. Osrreich (Berlin, 1980). I have benefited from conversations with Raoul Kneucker and Waltraud Heindl on this subject. 73. Erna Lesky, The Vienna Medical School of the Nineteenth Century, trans. J. Levij (Bal- timore, 1976). 74. Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (New York, 1%7). Like Dahrendorf's study of society and democracy in Germany, Hofstadrer's well-docu- Chapter2 mented book claims to be an exercise in civil courage more than an academic study. If they are accurate in describing their work, the importance of both of these books ought to tell us something about standard "academic" priorities. One important re- minder to American students of Austrian culture implicit in Hofsradrer's work is the closeness of American and Austrian forms of political fundamentalism. Schorske RETHINKING THE LIBERAL LEGACY himself has pointed out how the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a model to Schonerer (Schorske, Fin-de-Siecle Vienna, 129), whereas Pauley has indicated that the quotas on Jewish students that Viennese antisemites demanded in the 1930s ~ were already in effect at American elite institutions like Harvard (Pauley, From Prej- udice to Persecution, 94, 128). Pieter M Judson na review of Carl Schorske's influential Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics Iand Culture two decades ago, John Boyer noted the "uneven mono- graphic base" from which Schorske had drawn his portrayal of Austria's liberals. -

ECPAT International to the Council of Europe Lanzarote Committee

Submission on behalf of ECPAT International to the Council of Europe Lanzarote Committee General overview questionnaire on the implementation of the Lanzarote Convention January 2014 1 ECPAT International ECPAT international is a global network of civil society organisations, represented by 81 member groups in 74 countries. ECPAT International was the primary impetus behind the three World Congresses against the commercial sexual exploitation of children (Stockholm, Sweden – 1996; Yokohama, Japan – 2001; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – 2008), encouraging the world community to ensure that children everywhere enjoy their fundamental rights, free from all forms of commercial sexual exploitation. Through collaborative efforts, ECPAT encourages governments to adopt measures to strengthen their child protection policies in compliance with international child-rights standards and their international obligations. This includes advocating for policy changes to address gaps in legislation; formulation of national plans of action; creation of effective bilateral and multi-lateral agreements; and advocating for States to commit to the ratification of international treaties to protect children, such as the Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. ECPAT International has special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the UN (ECOSOC) and has received international recognition for its achievements, including the 2013 Conrad N. Hilton Humanitarian Prize. Collaboration with the private sector, as highlighted by the Stop Sex Trafficking of Children and Young People campaign, in partnership with The Body Shop, has drawn considerable recognition for ECPAT, including the praise of former US President Bill Clinton. The Campaign also led to one of the largest human rights petitions ever presented to the UN Human Rights Council in September 2011 (more than 7.2 million signatures), cementing ECPAT International’s reputation as a global leader in influencing social change. -

List of All Porno Film Studio in the Word

LIST OF ALL PORNO FILM STUDIO IN THE WORD 007 Erections 18videoz.com 2chickssametime.com 40inchplus.com 1 Distribution 18virginsex.com 2girls1camera.com 40ozbounce.com 1 Pass For All Sites 18WheelerFilms.com 2hotstuds Video 40somethingmag.com 10% Productions 18yearsold.com 2M Filmes 413 Productions 10/9 Productions 1by-day.com 3-Vision 42nd Street Pete VOD 100 Percent Freaky Amateurs 1R Media 3-wayporn.com 4NK8 Studios 1000 Productions 1st Choice 30minutesoftorment.com 4Reel Productions 1000facials.com 1st Showcase Studios 310 XXX 50plusmilfs.com 100livresmouillees.com 1st Strike 360solos.com 60plusmilfs.com 11EEE Productions 21 Naturals 3D Club 666 130 C Street Corporation 21 Sextury 3d Fantasy Film 6666 Productions 18 Carat 21 Sextury Boys 3dxstar.com 69 Distretto Italia 18 Magazine 21eroticanal.21naturals.com 3MD Productions 69 Entertainment 18 Today 21footart.com 3rd Degree 6969 Entertainment 18 West Studios 21naturals.com 3rd World Kink 7Days 1800DialADick.com 21roles.com 3X Film Production 7th Street Video 18AndUpStuds.com 21sextreme.com 3X Studios 80Gays 18eighteen.com 21sextury Network 4 Play Entertainment 818 XXX 18onlygirls.com 21sextury.com 4 You Only Entertainment 8cherry8girl8 18teen 247 Video Inc 4-Play Video 8Teen Boy 8Teen Plus Aardvark Video Absolute Gonzo Acerockwood.com 8teenboy.com Aaron Enterprises Absolute Jewel Acheron Video 8thstreetlatinas.com Aaron Lawrence Entertainment Absolute Video Acid Rain 9190 Xtreme Aaron Star Absolute XXX ACJC Video 97% Amateurs AB Film Abstract Random Productions Action Management 999 -

The Sexual Marketing of Eastern European Women Through Internet Pornography

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2010 The sexual marketing of eastern european women through internet pornography Karina Beecher DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Beecher, Karina, "The sexual marketing of eastern european women through internet pornography" (2010). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 33. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEXUAL MARKETING OF EASTERN EUROPEAN WOMEN THROUGH INTERNET PORNOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June, 2010 BY Karina Beecher Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Source: IOM Lisbon initiated Cooperação, Acção, Investigação, Mundivisão (CAIM) Project, Including a Public Awareness Campaign Against Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking. Eastern Europe Source: http://www.geocities.com/wenedyk/ib/easterneurope.html Contents Acknowledgments I. Introduction 1 II. Historical Context: The Rise of the Sex Industry in 4 Eastern Europe III. Literature Review 15 Feminist Debate Over Pornography 16 Pornography, Sexuality: Objectification and Commodification 20 Sexualizing Women Through Advertising in Media 26 Sexualizing Beauty and Whiteness 35 Rise of the Internet as a Space for the Sex Industry 43 IV. -

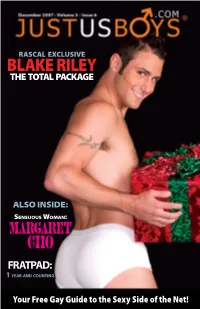

BLAKE RILEY T H E T O T a L P a C K a G E

RASCAL EXCLUSIVE BLAKE RILEY THE TOTAL PACKAGE ALSO INSIDE: SEN S UOU S WOMAN : Margaret CHO FRATPAD: 1 YEAR AND COUNTING Your Free Gay Guide to the Sexy Side of the Net! Full photo sets Full length streaming movies Live chat shows with the Fratmen Real college jocks and athletes in sizzling hot solo scenes Fratmen.TV JUSTUSBOYS.COM MAGAZINE • 5 8 • JUSTUSBOYS.COM MAGAZINE JUSTUSBOYS.COM MAGAZINE • 9 What’s Inside: Margaret Cho Corbin Fisher’s Real Couple: Charlie. He’s Brian Hansen reflects on and Brad Pat- hot! He’s sexy! 2007 with JUB. ton from COLT He’s straight! Studios. Page 14 Page 20 Page 36 Thanks for picking up the December 2007 issue of the JustUsBoys. DECEMBER 2007 com Magazine. What an exciting year it has been! This issue we VOLUME 3 look back on a few things that made 2007 such a great year. ISSUE 6 We start off with the self proclaimed fag-hag Margaret Cho. Mar- garet reflects on 2007 by telling us about her experience on the “True Colors Tour” and talks to JustUsBoys.com about her directo- rial debut of Two Sisters. Next we are excited to bring you an in- terview with Corbin Fisher’s Charlie. When Charlie first appeared - BLAKE RILEY - in the galleries on our website, fans went crazy. We thought it was only appropriate to share this beautiful stud with the rest of the world through our magazine. Don’t miss this hot interview. Also in this issue, we revisit the FratPad. Last year we brought you an exclusive look inside the FratPad and now the owners of this popular site invited us back to talk about what has happened in the past year and what has changed since our last visit. -

Gay Pornography and the First Amendment: Unique, First-Person Perspectives on Free Expression, Sexual Censorship, and Cultural Images Clay Calvert

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law Volume 15 | Issue 4 Article 2 2007 Gay Pornography and the First Amendment: Unique, First-Person Perspectives on Free Expression, Sexual Censorship, and Cultural Images Clay Calvert Robert D. Richards Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Calvert, Clay and Robert D. Richards. "Gay Pornography and the First Amendment: Unique, First-Person Perspectives on Free Expression, Sexual Censorship, and Cultural Images."American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law. 15, no. 1 (2006): 687-731. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Calvert and Richards: Gay Pornography and the First Amendment: Unique, First-Person Per GAY PORNOGRAPHY AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT: UNIQUE, FIRST-PERSON PERSPECTIVES ON FREE EXPRESSION, SEXUAL CENSORSHIP, AND CULTURAL IMAGES CLAY CALVERT* & ROBERT D. RICHARDS** Introduction ...............................................................................................688 -

Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015)

Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) Evangelos Tziallas A Thesis In the Department of The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Moving Image Studies Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada October 2015 © Evangelos Tziallas, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis is prepared By: Evangelos Tziallas Entitled: Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Film and Moving Image Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Chair Amy Swifen Examiner John Mercer Examiner Ara Osterweil Examiner Juliann Pidduck Supervisor Thomas Waugh Approved by Chair of Department of Graduate Program Director 2015 Dean of Faculty Abstract Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) Evangelos Tziallas, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2015 In this thesis I make the case for rethinking fictional and explicit queer representation as a form of surveillance. I put recent research in surveillance studies, particularly work on informational doubling, in conversation with the concepts of the uncanny and the doppelgänger to reconsider the legacy of screen theory and cinematic discipline in relation to the ongoing ideological struggle between normativity and queerness. I begin my investigation in and around the Stonewall era examining the gothic roots and incarnation of gay identity.