The Moving Body As Catalyst for Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22. MEL PATRICK the Author of This Site and the Book "Egocentricity and Spirituality"

22. MEL PATRICK The author of this site and the book "Egocentricity and spirituality" is not a guru, an enlightened being, a Jivanmukti or a Jnani (a realized person who holds sacred knowledge). He teaches nothing nor organizes sessions of meditation and Satsang (talks about spirituality and non-duality). He isn’t more or less "awakened" than anybody else when he doesn’t sleep in the arms of Morpheus. He doesn’t claim to be free from anything and doesn’t think to have realized the Self. He doesn’t live in Nirvana or in a world of non-duality, and even less in a fourth dimension of pure consciousness or in heaven, but on earth as all other human beings. He’s actually a very normal and ordinary human being and not God, the Self, the universal consciousness, stillness or an ocean of bliss. He writes to share his experience with other seekers of truth and what is according to him good for humanity. As a matter of fact, he is a seeker of truth and that’s why he doesn’t hesitate to denounce the delirious abuses of spirituality (especially in the non-duality circles) that we can witness today in the West. His initiation with Swami Girdanandaji from Uttarkashi and study of Advaita Vedanta with Mr. Brahma Chaitanya from Gangotri enable him to have a relatively clear idea of what is meant by the term "non-duality". And it’s precisely this subject that he wishes to introduce to the reader, subject based on an experience he has lived and very clearly described in the section "Experience" dated the 4/2/2012. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice. -

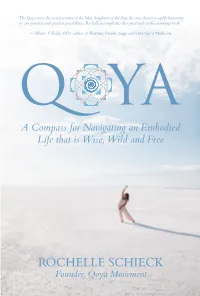

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

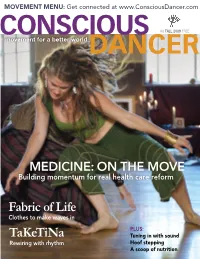

Taketina Tuning in with Sound Rewiring with Rhythm Hoof Stepping a Scoop of Nutrition

MOVEMENT MENU: Get connected at www.ConsciousDancer.com CONSCIOUS #8 FALL 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER MEDICINE: ON THE MOVE Building momentum for real health care reform Fabric of Life Clothes to make waves in PLUS: TaKeTiNa Tuning in with sound Rewiring with rhythm Hoof stepping A scoop of nutrition • PLAYING ATTENTION • DANCE–CameRA–ACtion • BREEZY CLEANSING American Dance Therapy Association’s 44th Annual Conference: The Dance of Discovery: Research and Innovation in Dance/Movement Therapy. Portland, Oregon October 8 - 11, 2009 Hilton Portland & Executive Tower www.adta.org For More Information Contact: [email protected] or 410-997-4040 Earn an advanced degree focused on the healing power of movement Lesley University’s Master of Arts in Expressive Therapies with a specialization in Dance Therapy and Mental Health Counseling trains students in the psychotherapeutic use of dance and movement. t Work with diverse populations in a variety of clinical, medical and educational settings t Gain practical experience through field training and internships t Graduate with the Dance Therapist Registered (DTR) credential t Prepare for the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) process in Massachusetts t Enjoy the vibrant community in Cambridge, Massachusetts This program meets the educational guidelines set by the American Dance Therapy Association For more information: www.lesley.edu/info/dancetherapy 888.LESLEY.U | [email protected] Let’s wake up the world.SM Expressive Therapies GR09_EXT_PA007 CONSCIOUS DANCER | FALL 2009 1 Reach -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

H J KRAMER ECKHART TOLLE EDITIONS NATARAJ PUBLISHING NAMASTE PUBLISHING Contents New Titles

NEW WORLD LIBRARY FALL 2018 H J KRAMER ECKHART TOLLE EDITIONS NATARAJ PUBLISHING NAMASTE PUBLISHING Contents New Titles The Meaning of Happiness............................................................................................2 The Holy Wild................................................................................................................3 Rescuing Ladybugs........................................................................................................4 The Resilience Toolkit.....................................................................................................5 The Divorce Hacker’s Guide to Untying the Knot..........................................................6 Mysterious Realities........................................................................................................7 The Emotionally Healthy Child......................................................................................8 Step into Your Moxie.....................................................................................................9 Jeff Herman’s Guide to Book Publishers, Editors & Literary Agents 2019..................10 The Life You Were Born to Live....................................................................................11 Feeling Better.............................................................................................................12 Smart Ass....................................................................................................................13 The Jewel of -

New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W

The New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-111-9 Published by Way of Life Literature P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) • [email protected] (e-mail) http://www.wayoflife.org (web site) Canada: Bethel Baptist Church, 4212 Campbell St. N., London, Ont. N6P 1A6 • 519-652-2619 (voice) • 519-652-0056 (fax) • [email protected] (e-mail) Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry 2 CONTENTS I. The New Age’s Vain Dream ....................................................5 II. Oprah Winfrey: The New Age High Priestess ......................10 III. My Experience in the New Age ..........................................27 IV. The New Age and the Mystery of Iniquity ..........................32 V. What Is the New Age? ..........................................................36 VI. The Origin of the New Age .................................................47 VII. How the New Age Evolved over the Past 100 Years .........61 The Stage Was Set at the Turn of the 20th Century The Mind Science Cults ................................................62 Christian Science ...........................................................64 Unity School of Christianity .........................................69 Helena Blavatsky and Theosophy .................................72 Alice Bailey ...................................................................80 The New Thought Positive-Confession Movement ......85 Aldous Huxley ..............................................................91 Alan -

Eckhart Tolle, "The Power of Now"

The Power of Now A Guide to SPIRITUAL ENLIGHTENMENT By Eckhart Tolle CONTENT Foreword ........................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 8 The Origin Of This Book .................................................................................................. 8 The Truth That Is Within You......................................................................................... 10 1. YOU ARE NOT YOUR MIND....................................................................................... 13 The Greatest Obstacle to Enlightenment......................................................................... 13 Freeing yourself from your mind .................................................................................... 16 Enlightenment: Rising above Thought............................................................................ 19 Emotion: The Body's Reaction to Your Mind................................................................. 21 2. CONSCIOUSNESS: THE WAY OUT OF PAIN ........................................................... 26 Create No More Pain In The Present............................................................................... 26 Past Pain: Dissolving The Pain-Body ............................................................................ -

The Emergence of Conspirituality’, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26(1): 103-121

The text that follows was written in 2009 and published as: Ward, Charlotte and Voas, David (2011) ‘The Emergence of Conspirituality’, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26(1): 103-121. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13537903.2011.539846?journalCode=cjcr20 The Emergence of Conspirituality Charlotte Ward & David Voas Abstract The female-dominated New Age (with its positive focus on self) and the male-dominated realm of conspiracy theory (with its negative focus on global politics) may seem antithetical. There is a synthesis of the two, however, that we call ‘conspirituality’. We define, describe, and analyse this hybrid system of belief; it has been noticed before without receiving much scholarly attention. Conspirituality is a rapidly growing web movement expressing an ideology fuelled by political disillusionment and the popularity of alternative worldviews. It has international celebrities, bestsellers, radio and TV stations. It offers a broad politico- spiritual philosophy based on two core convictions, the first traditional to conspiracy theory, the second rooted in the New Age: 1) a secret group covertly controls, or is trying to control, the political and social order, and 2) humanity is undergoing a ‘paradigm shift’ in consciousness. Proponents believe that the best strategy for dealing with the threat of a totalitarian ‘new world order’ is to act in accordance with an awakened ‘new paradigm’ worldview. Introduction The growth of industry, cities, and administrative structures has led to the separation and specialisation of social institutions. Individuals themselves occupy distinct roles (in the family, workplace, and community) that may no longer overlap. This social and personal fragmentation has caused conventional religion to become disconnected from everyday life. -

A Christian Response to Eckhart Tolle's: a New Earth: Awakening To

-An Open Letter to Oprah Winfrey and Eckhart Tolle- A Christian Response to Eckhart Tolle’s: A New Earth: Awakening to Your Lifes’ Purpose (By Dr. Ron Woodworth) Introduction I first heard of Eckhart Tolle when dear friends of ours mentioned they had, out of curiosity, ordered a copy of his latest book A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose, after hearing of it advertised on the Oprah Winfrey show. The more we discussed the content and popularity of the book the more certain I was that I should read, research, and write a response (rather than a reaction) from a “Christian” perspective.1 My objective here is to present an article that is informed by my experience as an adjunct professor of world religions,2 a seminary graduate,3 a published Christian apologist,4 5 and a former senior pastoral leader. Please know that in the article that follows there is absolutely no judgmentalism, resentment or vitriol in my intention. In fact, I am quite certain that Tolle and Winfrey are both sincerely seeking to bring awareness to many of those who have felt alienated from the irrelevance of legalistic “religion,” be it Christian or otherwise. I also share their concern. People are 1 hurting and are on a quest for healing, wholeness (harmony and alignment), and true meaning in life. Hence, rather than engage in an argumentative debate, my hope is that this article will at least help to clarify some fundamental issues between the worldview and subsequent spirituality recommended by Tolle vis-à-vis the biblical worldview and attending spirituality taught by Jesus Christ. -

Oprah Winfrey Loved It. Millions More Have Bought It. the Self

WW | wellbeing Oprah Winfrey loved it. Millions more have bought it. The self- help best-sellerHOW The Power of Now has turned German-born TO LIVE writer Eckhart Tolle into a spiritual guru, writes David Leser. HERE’S AN ADMISSION. I take Eck- rewarding experience of my career to teach your mind wrongly – you usually don’t use hart Tolle to bed with me every night. I this book online with Eckhart Tolle and it at all. It uses you. This is the disease. You share him with others, of course, but he’s witness millions of people all over the globe believe that you are your mind. This is the the constant companion. He’s the one awaken to their lives in such profound ways.” delusion. The instrument has taken over.” that’s always there. Sometimes, when I Oprah Winfrey isn’t the only celebrity Eckhart says the beginning of “freedom” don’t sleep, I turn to him for comfort or to have endorsed the teachings of this one- comes from the realisation that we are advice. At other times, deep in the grip of time homeless spiritual seeker. Meg Ryan not what we think, that a vast realm of some dream state, I feel him guarding the first recommended The Power of Now to intelligence exists beyond thought. night like my own personal shepherd. her and, in June 2007, Paris Hilton opted Thinking is only a tiny aspect of that Time magazine might have dismissed for Eckhart’s wise counsel when she intelligence and all the things that truly his teachings as New Age mumbo jumbo, entered the Century Regional Detention matter to us – beauty, creativity, joy, but I think the magazine is wrong, as do Facility in California on a driving offence. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.1: a - D

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.1: A - D © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E27 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.1: A - D Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others).