Note on a Colemanite Deposit Near Shoshone, Calif., with a Sketch Op the Geology of a Part of Amargosa Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Multi-Methodological Study of Kurnakovite: a Potential B-Rich 2 Aggregate 3 4 G

1 A multi-methodological study of kurnakovite: a potential B-rich 2 aggregate 3 4 G. Diego Gatta1, Alessandro Guastoni2, Paolo Lotti1, Giorgio Guastella3, 5 Oscar Fabelo4 and Maria Teresa Fernandez-Diaz4 6 7 1Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Milano, 8 Via Botticelli 23, I-20133 Milano, Italy 9 2Dipartmento di Geoscienze, Università degli Studi di Padova, 10 Via G. Gradenigo 6, I-35131, Padova, Italy 11 3Agenzia delle Dogane e dei Monopoli, Direzione Regionale per la Lombardia, 12 Laboratorio e Servizi Chimici, Via Marco Bruto 14, I-20138 Milan, Italy 13 4Institut Laue-Langevin, 71 Avenue des Martyrs, F-38000 Grenoble, France 14 15 16 Abstract 17 The crystal structure and crystal chemistry of kurnakovite from Kramer Deposit (Kern 18 County, California), ideally MgB3O3(OH)5·5H2O, was investigated by single-crystal neutron 19 diffraction (data collected at 293 and 20 K) and by a series of analytical techniques aimed to determine 20 its chemical composition. The concentration of more than 50 elements was measured. The empirical 21 formula of the sample used in this study is: Mg0.99(Si0.01B3.00)Σ3.01O.3.00(OH)5·4.98H2O. The fraction 22 of rare earth elements (REE) and other minor elements is, overall, insignificant. Even the fluorine 23 content, as potential OH-group substituent, is insignificant (i.e., ~ 0.008 wt%). The neutron structure 24 model obtained in this study, based on intensity data collected at 293 and 20 K, shows that the 25 structure of kurnakovite contains: [BO2(OH)]-groups in planar-triangular coordination (with the B- 2 26 ions in sp electronic configuration), [BO2(OH)2]-groups in tetrahedral coordination (with the B-ions 3 27 in sp electronic configuration), and Mg(OH)2(H2O)4-octahedra, connected in (neutral) 28 Mg(H2O)4B3O3(OH)5 units forming infinite chains running along [001]. -

Inyoite Cab3o3(OH)5 • 4H2O C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Inyoite CaB3O3(OH)5 • 4H2O c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Monoclinic. Point Group: 2/m. Typically as crystals, short prismatic along [001], tabular on {001}, exhibiting prominent {110} and {001} and a dozen other minor forms, to 2.5 cm; in cockscomb aggregates of pseudorhombohedral crystals; also coarse spherulitic, granular. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {001}, good; {010}, distinct. Fracture: Irregular. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 2 D(meas.) = 1.875 D(calc.) = 1.87 Soluble in H2O. Optical Properties: Transparent, translucent on dehydration. Color: Colorless, white on dehydration. Luster: Vitreous. Optical Class: Biaxial (–). Orientation: Y = b; X ∧ c =37◦; Z ∧ c = –53◦. Dispersion: r< v, slight. α = 1.490–1.495 β = 1.501–1.505 γ = 1.516–1.520 2V(meas.) = 70◦–86◦ Cell Data: Space Group: P 21/a. a = 10.621(1)) b = 12.066(1) c = 8.408(1) β = 114◦1.2◦ Z=4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Monte Azul mine, Argentina. 7.67 (100), 2.526 (25), 3.368 (22), 1.968 (22), 2.547 (21), 3.450 (20), 2.799 (19) Chemistry: (1) (2) B2O3 37.44 37.62 CaO 20.42 20.20 + H2O 9.46 − H2O 32.46 H2O 42.18 rem. 0.55 Total 100.33 100.00 • (1) Hillsborough, Canada; remnant is gypsum. (2) CaB3O3(OH)5 4H2O. Occurrence: Along fractures and nodular in sedimentary borate deposits; may be authigenic in playa sediments. Association: Meyerhofferite, colemanite, priceite, hydroboracite, ulexite, gypsum. Distribution: In the USA, in California, from an adit on Mount Blanco, Furnace Creek district, Death Valley, Inyo Co., and in the Kramer borate deposit, Boron, Kern Co. -

Alphabetical List

LIST L - MINERALS - ALPHABETICAL LIST Specific mineral Group name Specific mineral Group name acanthite sulfides asbolite oxides accessory minerals astrophyllite chain silicates actinolite clinoamphibole atacamite chlorides adamite arsenates augite clinopyroxene adularia alkali feldspar austinite arsenates aegirine clinopyroxene autunite phosphates aegirine-augite clinopyroxene awaruite alloys aenigmatite aenigmatite group axinite group sorosilicates aeschynite niobates azurite carbonates agate silica minerals babingtonite rhodonite group aikinite sulfides baddeleyite oxides akaganeite oxides barbosalite phosphates akermanite melilite group barite sulfates alabandite sulfides barium feldspar feldspar group alabaster barium silicates silicates albite plagioclase barylite sorosilicates alexandrite oxides bassanite sulfates allanite epidote group bastnaesite carbonates and fluorides alloclasite sulfides bavenite chain silicates allophane clay minerals bayerite oxides almandine garnet group beidellite clay minerals alpha quartz silica minerals beraunite phosphates alstonite carbonates berndtite sulfides altaite tellurides berryite sulfosalts alum sulfates berthierine serpentine group aluminum hydroxides oxides bertrandite sorosilicates aluminum oxides oxides beryl ring silicates alumohydrocalcite carbonates betafite niobates and tantalates alunite sulfates betekhtinite sulfides amazonite alkali feldspar beudantite arsenates and sulfates amber organic minerals bideauxite chlorides and fluorides amblygonite phosphates biotite mica group amethyst -

The Calcination Behaviour of Fine-Sized Colemanite and Ulexite

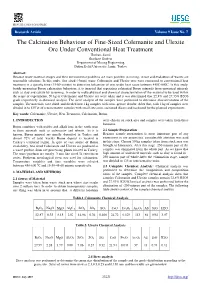

ISSN 2321 3361 © 2019 IJESC Research Article Volume 9 Issue No. 7 The Calcination Behaviour of Fine -Sized Colemanite and Ulexite Ore Under Conventional Heat Treatment Hoskan, Samil Graduate Student Department of Mining Engineering Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir, Turkey Abstract: Because waste material stroges and their enviromental problems are main problem in mining, re-use and evalaution of wastes are reasonable solutions. In this study, fine sized ( -3mm) waste Colemanite and Ulexite ores were exposured to conventional heat treatment in a spesific time (15-60 minute) to determine behaviour of ores under heat range bet ween 450C -600C. İn this study, beside measuring Boron calcination behaviour, it is targeted that seperating calcinated Boron minerals from unwanted minerals such as clay and calcite by screening. In order to make physical and chemical characterization of t he material to be used within the scope of experiments, 50 kg of Colemanite and Ulexite ore were taken and it was determined that 22,8% and 27,53% B2O3 grade respectively in chemical analysis. The sieve analysis of the samples were performed to determine c haracterization of the samples. The materials were dried and divided into 1 kg samples with cross -groove divider. After that, each 1 kg of samples were divided in to 125’gr of representative samples with small size cross -sectioned slicers and packaged for the planned experiments. Key words: Colemanite, Ulexite, Heat Treatment, Calcination, Boron . 1. INTRODUCTION were chosen on stock area and samples were taken from these locations. Boron combines with oxides and alkali ions in the earth crust to form minerals such as colemanite and ulexite. -

Cal Poly Geology Club Death Valley Field Trip – 2004

Cal Poly Geology Club Death Valley Field Trip – 2004 Guidebook by Don Tarman & Dave Jessey Field Trip Organizers Danielle Wall & Leianna Michalka DEATH VALLEY Introduction Spring 2004 Discussion and Trip Log Welcome to Death Valley and environs. During the next two days we will drive through the southern half of Death Valley and see some of the most spectacular geology and scenery in the United States. A detailed road log with mileages follows this short introductory section. We hope to keep the pace leisurely so that everyone can see as much as possible and have an opportunity to ask questions and enjoy the natural beauty of the region. IMPORTANT: WATER- carry and drink plenty. FUEL- have full tank upon leaving Stovepipe Wells or Furnace Creek (total driving distance approx. 150 miles). Participants must provide for their own breakfasts Saturday morning. Lunches will be prepared at the Stovepipe Wells campground before departing. We will make a brief stop at Furnace Creek visitor’s center and for fuel etc. Meeting Points Saturday morning meet in front at the Chevron station on the north side of the highway a short distance east of the campground (8:30 AM) Sunday morning (tentative- depending upon what our last stop is Saturday) meet at the Charles Brown highway intersection with 127 just at the south side of Shoshone. (8:30 AM). Get fuel before meeting. As you know we will be camping Saturday night between the hamlets of Shoshone and Tecopa. If for some reason you become separated from the main caravan during our journey Saturday – and this would be very difficult to accomplish- simply head for Shoshone/Tecopa. -

Death Valley National Monument

DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL MONUMENT CALIFORNIA NEVADA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL MONUMENT Contents DEATH VALLEY FROM BREAKFAST CANYON Cover Open all year • Regular season, October 15 to May 15 BEFORE WHITE MEN CAME 3 THE HISTORICAL DRAMA 4 cipitation at headquarters during the past TALES WRITTEN IN ROCK AND LANDSCAPE 5 DEATH VALLEY National Monument is distinguished by its desert scenery— 15 years has been 2.03 inches. DESERT WILDLIFE 10 a combination of unusual geology, flora, Summer daytime temperatures in the DESERT PLANTLIFE 11 fauna, and climate. Famed as a scene of valley itself are quite high. The maxi suffering in the gold-rush drama of mum air temperature of 134° F. in the INTERPRETIVE SERVICES 12 1849, Death Valley has long been shade recorded in Death Valley was a WHAT TO SEE AND DO WHILE IN THE MONUMENT 12 known to scientist and layman alike as world record until 1922 when 136.4° F. HOW TO REACH DEATH VALLEY 13 a region rich in scientific and human was reported from El Azizia, Libya. interest. The monument was established Higher locations on the mountains in the MONUMENT SEASON 14 in 1933 and covers almost 3,000 square monument have comfortable daytime WHAT TO WEAR 14 miles. temperatures and cool nights. ACCOMMODATIONS 14 The monument is in the rugged desert From late October until May, the val ADMINISTRATION 15 region east of the Sierra Nevada in east ley climate is usually very pleasant. ern California and southwestern Nevada. Days are often warm and sunny, nights PLEASE HELP PROTECT THIS MONUMENT 15 The valley itself is about 140 miles long, cool and invigorating, with the temper with the forbidding Panamint Range ature seldom below freezing. -

Borax: History & Uses Borax Belongs to a Group of Boron Minerals Called Borates Resembling Quartz Crystals, Fibrous Cottonballs Or Earthy White Powders

Borax: History & Uses Borax belongs to a group of boron minerals called borates resembling quartz crystals, fibrous cottonballs or earthy white powders. They originated in hot springs or vapors associated with the outpouring of volcanic rocks such as the colorful formations of Artists Drive. Seeping groundwater formed glassy borate veins in the extinct lakebeds of Furnace Creek and has moved soluble borates to modern salt flats such as the floor of Death Valley. There, evaporation has left a mixed white crust of salt, borax and alkalies. The history of borax in America began in earnest with the borax boom of the 1870s, when many California and Nevada salt flats were claimed by prospectors. One was Aaron Winters, who used the famous green-flame test to locate borax on a Death Valley salt marsh in 1881. His claims were soon purchased by W.T. Coleman, builder of Harmony Borax Works, where marsh muds were refined until 1889. The contemporary Eagle Borax Works folded in 1882 because of poor depos-its, summer heat and remoteness. Coleman’s company beat the heat by moving summer operation to the Amargosa Works near less- torrid Shoshone. The transportation problem was solved by hitching 20-mule teams to gigantic borax wagons with a payload in tandem of over 20 tons. By 1890, salt marsh operations were obsolete and F.M. “Borax” 20 Mule Team Wagon. Photo Courtesy of NPS. Smith consolidated most claims in the Pacific Coast Borax Company. He concentrated on mining glassy veins of a rich new borate in the Calico Mountains, south of Death Valley. -

Densitie @F Minerals , and ~Ela I Ed

Selecte,d , ~-ray . ( I Crystallo ~raphic Data Molar· v~ lumes,.and ~ Densitie @f Minerals , and ~ela i ed. Substances , GEO ,LOGICAL ~"l!JRVEY BULLETIN 1248 I ' " \ f • . J ( \ ' ' Se Iecte d .L\.-ray~~~T Crystallo:~~raphic Data Molar v·olumes, and Densities of Minerals and Related Substances By RICHARD A. ROBIE, PHILIP M. BETHKE, and KEITH M. BEARDSLEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1248 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1967 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 67-276 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 3 5 cents (paper cover) OC)NTENTS Page Acknowledgments ________ ·-·· ·- _____________ -· ___ __ __ __ __ __ _ _ __ __ __ _ _ _ IV Abstract___________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction______________________________________________________ 1 Arrangement of data _______ .. ________________________________________ 2 X-ray crystallographic data of minerals________________________________ 4 Molar volumes and densities. of minerals_______________________________ 42 References_________________________________________________________ 73 III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We wish to acknowledge the help given in the preparation of these tables by our colleagues at the U.S. Geological Survey, particularly Mrs. Martha S. Toulmin who aided greatly in compiling and checking the unit-cell parameters of the sulfides and related minerals and Jerry L. Edwards who checked most of the other data and prepared the bibliography. Wayne Buehrer wrote the computer program for the calculation of the cell volumes, molar volumes, and densities. We especially wish to thank Ernest L. Dixon who wrote the control programs for the photo composing machine. IV SELECTED X-RAY CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC DATA, MOLAR VOLUMES, AND DENSITIES OF !'.IINERALS AND RELATED SUBSTANCES By RICHARD A. -

Download the Scanned

AmericanMineralogist, Volume64, pages 369-375, 1979 Newdata on hungchaoite,the second world occurrence, Death Valley region, California RtcHnRoC. Eno, Jluss F. McAlr-rsrER ANDG. DoNeln EsrnI-urN U.S. GeologicalSuruey Menlo Park, Califurnia 94025 Abstract Hungchaoiteoccurs with ginorite,mcallisterite, sborgite, sassolite, nobleite, ulexite, and, wheregypsum and ulexiteare abundant,with kurnakovite.inderite. and mcallisteritein surficialmatrix as productsfrom weatheredcolemanite and priceiteveins in late Tertiary rocks. Hungchaoiteis triclinic,space group PT;a :8.811(1), b : 10.644(2),c : 7.888(l)A;a : 103"23(l)',0 : 108o35(l)', 97.09(l), unit-cellvolume 666.2(l)Aa;Z 2[MgO.4BrOs.9HrO].Euhedral, tabular {100} to equant,colorless, untwinned crystals, up to 0.5mm, showl7 forms.The strongest lines in theX-ray powder pattern are, in A: 6.71(100), 3.3s6(92), 5.36(85 ), 4.093(78), 4.079(64), and 7.I 4(59). Hungchaoiteisoptically(-):*:1.445(2),0=1.485(2),7:l.a9}Q)(Nalight);2Il": ( -66.. 15(4)";r u,distinct; Xlta: +28",2Lb = 437",Y4 c = Good{lll}and {lll}and imperfect{010} cleavages. Hardness 2Yz. G (meas)1.706(5), p (calc)1.705 g cm-s. Hungchaoiteis metastablewith respectto inderite and mcallisteritein solution. Dehy- dration data are given. Introduction of DeathValley National Monument. The first local- ity is about 50 m southwestof the road in Twenty Hungchaoite,MgO.2BrO3.9H2O, was first de- Mule TeamCanyon, 2,140 m N25'W of U.S.mineral scribedby (1964a,b) Chu et al. from salinelacustrine monument40 on Monte Blanco(McAllister, 1970), sedimentsat an unspecified localityin Chinawhere it andis in thesoutheastern part of the Meridianclaim. -

COLEMANITE Safety Data Sheet

COLEMANITE Safety Data Sheet www.keramikos.nl In compliance with Regulation (EC)1907/2006 (REACH) Regulation (EC) 1272/2008 (CLP) Date of issue: 03/03/2011 Revision date: 07/05/2015 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE AND THE COMPANY 1.1 Identification of the substance Name of the substance: Colemanite Annex VI Index number: CAS number: 12291-65-5 EC number: - REACH registration number: Exempted from registration under REACH Regulation according to Article 2(7)(b). Colemanite is a natural occurring mineral which is not chemically modified, therefore, considered within the scope of Annex V of the REACH Regulation. Synonyms: Calcium borate, di-calcium hexaborate pentahydrate Chemical formula Ca2B6O11.5H2O , (2CaO.3B2O3.5H2O) Molecular weight: 411,08 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance and uses advised against Identified uses: The product is used in industrial manufacturing, in particular in: Textile grade fibreglass Boron alloys Metallurgical fluxing Borosilicate glass 1.3 Supplier identification Supplier: Keramikos Oudeweg 153 2031 CC Haarlem 1.4 Emergency telephone number 023 – 542 44 16 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION 2.1 Classification of the substance 2.1.1 Classification of the substance according to Regulation (EC) Nr. 1272/2008 [CLP] No classification 2.1.2 Classification of the substance according to Directive 67/548/CEE No classification SDS Ref:– 07-05-2015 Page 1 COLEMANITE Safety Data Sheet In compliance with Regulation (EC)1907/2006 (REACH) Regulation (EC) 1272/2008 (CLP) Date of issue: 03/03/2011 Revision date: 07/05/2015 2.2 Labelling of the substance 2.2.1 Labelling of the substance according to Regulation (EC) Nr. -

New Mineral Names*

AmericanMineralogist, Volume 80, pages 1328-1333,1995 NEW MINERAL NAMES* JonN L. Janson Department of Earth Sciences,University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3Gl, Canada J.lcnx Pvztnwtcz Institute of Geological Sciences,University of Wroclaw, Cybulskiego30, 50-205 Wroclaw, Poland ANunnw C. Ronnnrs Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street,Ottawa, Ontario KlA 0E8, Canada Alarsite* rhtinite, but the synthetic phaseis much higher in Ti and T.F. Semenova,L.P. Vergasova,S.K. Filatov, V.V. An- lacks Fe. anev (1994) Alarsite AlAsOo: A new mineral from vol- Discussion.Known only as a synthetic product; not a canic exhalations.Doklady Akad. Nauk, 338(4),501- valid mineral name. J.L.J. 505 (in Russian). Electron microprobe analysis (averageof 20) gave AlrO. 31.98,FerO, 0.60, CuO 0.54,AsrO, 66.71,sum 99.83 Crawfordite* wt0/0,corresponding to Al, ooFefig,Cufrj,AsonuOo.Occurs as A.P. Khomyakov, L.I. Polezhaeva,E.V. Sokolova(1994) colorlessaggregates with yellowish, pale green,and bluish Crawfordite NarSr(POo)(COr):A new mineral from the tints, commonly containing powdery hematite or tenorite bradleyite group. Zapiski Vseross. Mineral. Obshch., and gaseousinclusions; also as equant grains to 0.3 mm 123(3),4l -49 (in Russian). in diameter, some with poorly developed faces.Vitreous Electron microprobe analysis (averageof two grains) luster, white streak, brittle, no cleavage, VHNro: 449 gaveNarO 31.83,KrO 0.22,CaO 1.45,SrO 27.42,P2O5 (336-480),D-""" : 3.32(l),D*r.: 3.34g,/cm3 for Z : 3. 23.64, CO2(calculatedfrom X-ray structural data) 14.47, Stableat atmospheric conditions; soluble in dilute acids. -

Download the Scanned

PLATE 15 Colruenrrn psEUDoMoRpHous aFTER rNyorrp FRoM Dpern Var,r,nv. Cer,rronwte TnB AunnICAN MrxnnALocIST Vor,. 4 NOVEMBER, 1919 No. 11 COLEMANITE PSEUDOMORPHOUS AFTER INYOITE FROM DEATH VALLEY. CALIFORNIA AUSTIN F. ROGERS S tanJord U niaersitg, Calif ornia The frontispieceof this number is a photograph of an interest- ing specimenpresented to the geologydepartment of Stanford University by the late Mr. C. A. W-aringof the California State Mining Bureau. This, and a similar specimenin the department, museum collectedby Mr. H. P. Knight, are from the Biddy McOarty mine of the Pacific CoasLBorax Company in Death Valley, Inyo County, California. The specimenshown in the photographwas labeled in the field "colemanite after calcite," while the other specimenwas labeled "rare form of calcium borate." Frc. 1. Forrn of original inyoite. Cnysrer, Fonlr The material of both specimens proves to be colemanite, but the original mineral was inyoite, a hydrous calcium borate recently describedby Schallerl from the same region. The crystals, on closeexamination, prove to be monoclinic instead of hexagonal as at first supposed. The forms present are: c (001),m (ll0), b (010),and p (111). The habit is tabular parallelto c (001)as representedin Fig. l. The following inter- I U. S.Geol. Suruey, BuIl.6lO, tt,rtJ't6. 136 THE aMEnICAN MINEuaLIGIST facial angles, (each the average of ten values with the limits stated) weremeasured with a contact goniometer: ADgle Schaller'g Value 773"-79+" 7802L', 79" 45', 7t -72 71 36 69 20 883-e0+ 89 34 900 63+-65* 64 31 62 37 37 -39 37 57 36 15 32?-35 33 54 335 These measurementsclearly prove that the form is that of inyoite, but it is believed that the,average angles given are closerto the truth than those given by Schaller,in spite of the fact that the crystals are pseudomorphs.