The Iwo Jima Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 the Bottom Line C-3

INSIDE National Anthem A-2 2/3 Air Drop A-3 Recruiting Duty A-6 Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 The Bottom Line C-3 High School Cadets D-1 MVMOLUME 35, NUMBER 8 ARINEARINEWWW.MCBH.USMC.MIL FEBRUARY 25, 2005 3/3 helps secure clinic Marines maintain security, enable Afghan citizens to receive medical treatment Capt. Juanita Chang Combined Joint Task Force 76 KHOST PROVINCE, Afghanistan — Nearly 1,000 people came to Khilbasat village to see if the announcements they heard over a loud speaker were true. They heard broadcasts that coalition forces would be providing free medical care for local residents. Neither they, nor some of the coalition soldiers, could believe what they saw. “The people are really happy that Americans are here today,” said a local boy in broken English, talking from over a stone wall to a Marine who was pulling guard duty. “I am from a third-world country, but this was very shocking for me to see,” said Spc. Thia T. Valenzuela, who moved to the United States from Guyana in 2001, joined the United States Army the same year, and now calls Decatur, Ga., home. “While I was de-worming them I was looking at their teeth. They were all rotten and so unhealthy,” said Valenzuela, a dental assistant from Company C, 725th Main Support Battalion stationed out of Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. “It was so shocking to see all the children not wearing shoes,” Valenzuela said, this being her first time out of the secure military facility, or “outside the wire” as service members in Afghanistan refer to it. -

Henry Hansen Memorial Park Somerville, MA

Community Meeting #1 Henry Hansen Memorial Park Somerville, MA AGENDA • Introductions • Design Schedule • History • Existing Conditions & Site Analysis • Possible Precedents • Questions for Discussion Monday March 26, 2018 PROJECT OVERVIEW HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC PROJECT OVERVIEW INTRODUCTIONS City of Somerville Bryan Bishop, Commissioner of Veterans’ Services CBA Landscape Architects LLC D.J. Chagnon, Principal-in-Charge & Project Manager Jessica Choi & Liz Thompson, Staff Landscape Designers HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC DESIGN SCHEDULE PROJECT OVERVIEW Community Meeting 1 (March 26, 2018): Present history, site analysis, and precedents. Gather community input, and develop wish list to guide Schematic Designs for future meetings. Community Meeting 2 (Late April 2018:) Present Schematic Design Alternatives based on first meeting input. Community review and discussion, with the goal of developing a final Preferred Design Plan. Community Meeting 3 (Early June 2018): Present Definitive Design for park construction, including features and site furnishings based on community discussion at Meeting 2. With community input, discuss project budget, bidding process, suggested Alternates, and prioritize strategy to maximize budget. Design Development (Summer 2018): CBA will further develop and refine Definitive Design. Funding Application (Fall 2018): City of Somerville will apply for Funding. Construction Documents (Winter - Spring 2019): CBA will finalize Definitive Design and suggested Alternates into detailed Construction Documents suitable for bidding purposes. Construction Start (Late Spring - Summer 2019) HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC VISION PROJECT OVERVIEW To renovate Henry Hansen Park - a small gem of Somerville’s park system with an important story to tell in both local and national history. -

Spearhead-Fall-Winter-2019.Pdf

Fall/Winter 2019 SpearheadOFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the 5TH MARINE DIVISION NEWS“Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue” ASSOCIATION OCTOBER 22 - 25, 2020 71ST ANNUAL REUNION DALLAS, TEXAS Sons of Iwo vets take the helm of FMDA Bruce Hammond and statue in Semper Fi Tom Huffhines, both Memorial Park at the native Texans and sons Marine Corps War of Iwo Jima veterans Museum at Quantico, who previously (Triangle) Va., and served as Association had long worked with presidents and reunion the FMDA. hosts, were selected to Continuing his lead the Fifth Marine father’s work with the Division Association Association, President as president and vice Bruce Hammond said, president, respectively, “It is important that we for the next year. channel our passion, Additionally, move forward and lifetime FMDA mem- President Bruce Hammond and Vice President Tom Huffhines focus on our mission ber, Army helicopter for our Marine veterans.” pilot and Vietnam veteran John Powell volunteered to Vice President John Huffhines agreed and said, host the next FMDA reunion from Oct. 22-25, 2020, in “Communication with the membership, as good and Dallas. as often as possible, is extremely key to its existence. Hammond’s father, Ivan (5th JASCO), hosted the Stronger fundraising ideas and efforts should be the 2016 reunion in San Antonio, Texas, when John Butler main thing on each of our agendas.” was president, and in Houston, Texas, in 2009 when he Hammond graduated from the University of Texas, was president himself. Austin, in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Huffhines’ father, John (HS 2/3), hosted the 2006 He worked for 24 years as a well-site drilling-fluids reunion in Irving, Texas, when he was president. -

79-Years Ago on December 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

The December 7, 2020 American Indian Tribal79 -NewsYears * Ernie Ago C. Salgado on December Jr.,CE0, Publisher/Editor 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii America Entered World War II 85-90 Million People Died WW II Ended - Germany May 8, 1945 & Japan, September 2, 1945 All the Nations involved in the war threw and a majority of it has never been recovered. Should the Voter Fraud succeed in America their entire economic, industrial, and scien- Japan, which aimed to dominate Asia and the and the Democratic Socialist Party win the tific capabilities behind the war effort, blur- 2020 Presidential election we will become Pacific, was at war with China by 1937. ring the distinction between civilian and mili- Germany 1933. World War II is generally said to have begun tary resources. on 1 September 1939, with the invasion of And like Hitler’s propaganda news the main World War II was the deadliest conflict in hu- Poland by Germany and subsequent declara- stream media and the Big Tech social media man history, marked by 85 to 90 million fatal- tions of war on Germany by France and the fill that role. ities, most of whom were civilians in the So- United Kingdom. We already have political correctness which is viet Union and China. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of anti-free speech, universities and colleges that It included massacres, the genocide of the campaigns and treaties, Germany conquered prohibit free speech, gun control, judges that Jews which is known as the Holocaust, strate- or controlled much of continental Europe, and make up their own laws, we allow the mur- gic bombing, premeditated death from starva- formed alliance with Italy and Japan. -

Dedication Marine Corps War Memorial

• cf1 d>fu.cia[ CJI'zank 'Jjou. {tom tf'u. ~ou.1.fey 'Jou.ndation and c/ll( onumE.nt f]:)E.di catio n eMu. §oldie. ~~u.dey 9Jtle£: 9-o't Con9u~ma.n. ..£a.uy J. dfopkira and .:Eta(( Captain §ayfc. df. cf?u~c., r"Unitc.d 2,'tat~ dVaay cf?unac. c/?e.tiud g:>. 9 . C. '3-t.ank.fin c.Runyon aow.fc.y Captain ell. <W Jonu, Comm.andtn.9 D((kn, r"U.cS.a. !lwo Jima ru. a. o«. c. cR. ..£ie.utenaJZI: Coforuf c.Richa.t.d df. Jetl, !J(c.ntucky cflit dVa.tionaf §uat.d ..£ieuienant C!ofond Jarnu df. cJU.affoy, !J(wtucky dVa.tional §uat.d dU.ajo"< dtephen ...£. .::Shivc.u r"Unit£d c:Sta.tu dU.a.t.in£ Cotp~ :Jfu. fln~pul:ot.- fl~huclot. c:Sta.{{. 11/: cJU.. P.C.D., £:ci.n9ton., !J(!:J· dU.a1tn c:Sc.1.9c.a.nt ...La.ny dU.a.'ltin, r"Unltc.d c:Stal£~ dU.a.t.lnc. Cot.pi cR£UW£ £xi1t9ton §t.anite Company, dU.t.. :Daniel :be dU.at.cUJ (Dwnc.t.} !Pa.t.li dU.onurncn.t <Wot.ki, dU.t. Jim dfifk.e (Dwn£"tj 'Jh£ dfonowbf£ Duf.c.t. ~( !J(£ntucky Cofone£. <l/. 9. <W Pof.t dVo. 1834, dU.t.. <Wiffu df/{~;[ton /Po1l Commarzdz.t} dU.t.. Jarnu cJU.. 9inch Jt.. dU.t.. Jimmy 9tn.ch. dU.u. dVo/J[~; cflnow1m£th dU.u. 'Je.d c:Suffiva.n dU.t.. ~c. c/?odt.'9uc.z d(,h. -

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots by NATHANIEL S. PATCH n the morning of September 2, 1944, the submarine USS OFinback was floating on the surface of the Pacific Ocean—on lifeguard duty for any downed pilots of carrier-based fighters at- tacking Japanese bases on Bonin and Volcano Island. The day before, the Finback had rescued three naval avi- near Haha Jima. Aircraft in the area confirmed the loca- ators—a torpedo bomber crew—from the choppy central tion of the raft, and a plane circled overhead to mark the Pacific waters near the island of Tobiishi Bana during the location. The situation for the downed pilot looked grim; strikes on Iwo Jima. the raft was a mile and a half from shore, and the Japanese As dawn broke, the submarine’s radar picked up the in- were firing at it. coming wave of American planes heading towards Chichi Williams expressed his feelings about the stranded pilot’s Jima. situation in the war patrol report: “Spirits of all hands went A short time later, the Finback was contacted by two F6F to 300 feet.” This rescue would need to be creative because Hellcat fighters, their submarine combat air patrol escorts, the shore batteries threatened to hit the Finback on the sur- which submariners affectionately referred to as “chickens.” face if she tried to pick up the survivor there. The solution The Finback and the Hellcats were starting another day was to approach the raft submerged. But then how would of lifeguard duty to look for and rescue “zoomies,” the they get the aviator? submariners’ term for downed pilots. -

Closingin.Pdf

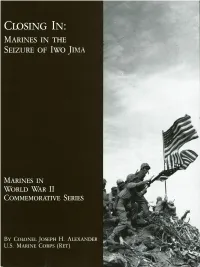

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

Teacher's Guide for Quiet Hero the Ira Hayes Story

Lee & Low Books Quiet Hero Teacher’s Guide p.1 Classroom Guide for QUIET HERO: THE IRA HAYES STORY by S.D. Nelson Reading Level *Reading Level: Grades 4 UP Interest Level: Grades 2-8 Guided Reading Level: P Lexile™ Measure: 930 *Reading level based on the Spache Readability Formula Themes Heroism, Patriotism, Personal Courage, Loyalty, Honor, World War II, Native American History National Standards SOCIAL STUDIES: Culture; Individual Development and Identity; Individuals, Groups, and Institutions LANGUAGE ARTS: Understanding the Human Experience; Multicultural Understanding Born on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona, Ira Hayes was a bashful boy who never wanted to be the center of attention. At the government-run boarding school he attended, he often felt lonely and out of place. When the United States entered World War II, Hayes joined the Marines to serve his country. He thrived at boot camp and finally felt as if he belonged. Hayes fought honorably on the Pacific front and in 1945 was sent with his battalion to Iwo Jima, a tiny island south of Japan. There he took part in the ferocious fighting to secure the island. On February 23, 1945, Hayes was one of six men who raised the American flag on the summit of Mount Suribachi at the far end of the island. A photographer for the Associated Press, Joe Rosenthal, caught the flag- raising with his camera. Rosenthal’s photo became an iconic image of American courage and is one of the best-known war pictures ever taken. The photograph also catapulted Ira Hayes into the role of national hero, a position he felt he hadn’t earned. -

Two US Navy's Submarines

Now available to the public by subscription. See Page 63 Volume 2018 2nd Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Special Election Issue USS Thresher (SSN-593) America’s two nuclear boats on Eternal Patrol USS Scorpion (SSN-589) More information on page 20 Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN List 978-0-9896015-0-4 American Submariner Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 2 Page 3 Table of Contents Page Number Article 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission 4 USSVI National Officers 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees AMERICAN 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer 6 Message from the Chaplain SUBMARINER 7 District and Base News This Official Magazine of the United 7 (change of pace) John and Jim States Submarine Veterans Inc. is 8 USSVI Regions and Districts published quarterly by USSVI. 9 Why is a Ship Called a She? United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 9 Then and Now is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 10 More Base News in the State of Connecticut. 11 Does Anybody Know . 11 “How I See It” Message from the Editor National Editor 12 2017 Awards Selections Chuck Emmett 13 “A Guardian Angel with Dolphins” 7011 W. Risner Rd. 14 Letters to the Editor Glendale, AZ 85308 18 Shipmate Honored Posthumously . (623) 455-8999 20 Scorpion and Thresher - (Our “Nuclears” on EP) [email protected] 22 Change of Command Assistant Editor 23 . Our Brother 24 A Boat Sailor . 100-Year Life Bob Farris (315) 529-9756 26 Election 2018: Bios [email protected] 41 2018 OFFICIAL BALLOT 43 …Presence of a Higher Power Assoc. -

THE GRUNT the Lakeland Grunt, PO Box 0008, Pompton Lakes, NJ 07442 April 2014 March 2015 Mike Mcnulty –Editor 732-213-5264

Lakeland Detachment #744 THE GRUNT The Lakeland Grunt, PO Box 0008, Pompton Lakes, NJ 07442 April 2014 March 2015 Mike McNulty –Editor 732-213-5264 Your Officers for 2015 Commandants Corner Charles Huha-Commandant 973-835-2315 [email protected] Michael McNulty—Sr. Vice 732-213-5264 Marine Corps League [email protected] Lakeland Detachment—744 Kevin O’Leary -Jr. Vice 201-644-8078 March 2015 [email protected] On February 18, 2015, Detachment member Dave Peter Alvarez—Paymaster/Adj 973-839-5693 Elshout and I had the distinct pleasure of having din- [email protected] ner with a Marine giant, Zigmund “Ziggy” Gasiewicz. We joined Ziggy, his son Peter, Nephew, Louis, both Paul Thompson Service Officer 201-651-1822 Marines, and other family members and Marines for [email protected] a wonderful night of sharing and being with a legend, Ray Sears– Judge Advocate 973-694-8457 up close and personal. Ziggy will be 94 in July. He [email protected] joined the Marine Corps in 1940 while still a teenag- er. After Parris Island, he served at Guantanamo Theresa Muttel– Secretary 973-764-9565 Bay and did practice assaults in the islands off of [email protected] Puerto Rico. After Pearl Harbor, he was sent to Cali- fornia for training, then to New Zealand and the Fiji Bill De Lorenzo—Legal Officer 201-337-6677 Islands for more training. His ultimate destination [email protected] was Guadalcanal. Dennis Kievit—Chaplain 201-825-0183 Ziggy hit Guadalcanal as a 75 mil pack Howitzer ar- [email protected] tillery man. -

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish Explorer Don

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish explorer Don Gasper de Portola first scouted the area where Camp Pendleton is located in 1769. He named the Santa Margarita Valley in honor of St. Margaret of Antioch, after sighting it July 20, St. Margaret's Day. The Spanish land grants, the Rancho Santa Margarita Y Las Flores Y San Onofre came in existence. Custody of these lands was originally held by the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, located southeast of Pendleton, and eventually came into the private ownership of Pio Pico and his brother Andre, in 1841. Pio Pico was a lavish entertainer and a politician who later became the last governor of Alto California. By contrast, his brother Andre, took the business of taming the new land more seriously and protecting it from the aggressive forces, namely the "Americanos." While Andre was fighting the Americans, Pio was busily engaged in entertaining guests, political maneuvering and gambling. His continual extravagances soon forced him to borrow funds from loan sharks. A dashing businesslike Englishman, John Forster, who has recently arrived in the sleepy little town of Los Angeles, entered the picture, wooing and winning the hand of Ysidora Pico, the sister of the rancho brothers. Just as the land-grubbers were about to foreclose on the ranch, young Forster stepped forward and offered to pick up the tab from Pio. He assumed the title Don Juan Forster and, as such, turned the rancho into a profitable business. When Forster died in 1882, James Flood of San Francisco purchased the rancho for $450,000. -

Flags of Our Fathers

SURVIVORS RAISE CASH via WAR BONDS 0. SURVIVORS RAISE CASH via WAR BONDS - Story Preface 1. A PACIFIC EMPIRE 2. DANGEROUS OPPONENTS 3. DEATH IN CHINA 4. ATROCITIES IN CHINA 5. ABOUT IWO JIMA 6. THE ARMADA ARRIVES 7. JAPAN'S IWO JIMA DEFENSES 8. LETTERS FROM IWO JIMA 9. JUST A MOP-UP? 10. D-DAY: 19 FEBRUARY 1945 11. THE UNBROKEN CODE 12. INCHING TOWARD SURIBACHI 13. A FLAG-RAISING ON SURIBACHI 14. THE REPLACEMENT FLAG RAISERS 15. THE FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPH 16. FLAG RAISERS DIE IN BATTLE 17. KURIBAYASHI'S LAST LETTERS 18. SECURING IWO JIMA 19. IWO JIMA MEDALS OF HONOR 20. SURVIVORS RAISE CASH via WAR BONDS 21. WHY IWO JIMA WAS CAPTURED 22. FIRE BOMBS OVER TOKYO 23. RESULTS of WAR 24. THE REST OF THEIR LIVES 25. EPILOGUE - EARTHQUAKE in JAPAN 26. Awesome Guide to 21st Century Research Example of a WWII-era war bond, used by the federal government to fund the war effort. US National Archives. Paying for both world wars did not come directly from the U.S. federal budget. Money was not just taken, as it were, through taxes. American citizens, including children - like students from Chicago's South-Central School District who raised $263,148.83 (that’s about $3 million in today’s dollars) - loaned the government money through war bonds. If a person invested $18.75 in a war bond, for example, the government would repay that amount in ten years. In fact, the investor would make money on such a loan because the U.S. Treasury repaid $25 for the matured bond.