Growing up in University School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin #26 June 30, 2018

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #26 June 30, 2018 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, June 30, 2018 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (Legislation was signed by Council President Shannon Hardin on the night of the Council meeting, Monday, June 25, 2018; Ordinances 1633-2018 and 1637-2018 were returned unsigned by Mayor Andrew J. Ginther on Tuesday, June 26, 2018; Mayor Ginther signed all of the other legislation on Wednesday, June 27, 2018; All of the legislation included in this edition was attested by the City Clerk, prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 06/30/18) 2 of 196 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 06/30/18) 3 of 196 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH 43215-9015 Minutes - Final columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council ELECTRONIC READING OF MEETING DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE DURING COUNCIL OFFICE HOURS. CLOSED CAPTIONING IS AVAILABLE IN COUNCIL CHAMBERS. -

Greater Columbus Arts Council 2016 Annual Report

2016 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY SUPPORTING ART. ADVANCING CULTURE. LETTER FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND PRESIDENT In 2016 the Greater Columbus Arts Council made substantial progress toward building 84,031 a more sustainable arts sector in Columbus. An unprecedented year for the bed tax in 2016 resulted in more support to artists and ARTIST PROFILE arts organizations than ever before. Twenty-seven Operating Support grants were awarded totaling $3.1 million and 57 grants totaling $561,842 in Project Support. VIDEO VIEWS The Art Makes Columbus/Columbus Makes Art campaign generated nearly 400 online, print and broadcast stories, $9.1 million in publicity and 350 million earned media impressions featuring the arts and artists in Columbus. We held our first annual ColumbusMakesArt.com Columbus Open Studio & Stage October 8-9, a self-guided art tour featuring 26 artist studios, seven stages and seven community partners throughout Columbus, providing more than 1,400 direct engagements with artists in their creative spaces. We hosted another outstanding Columbus Arts Festival on the downtown riverfront 142% and Columbus’ beautiful Scioto Greenways. We estimated that more than 450,000 people enjoyed fine artists from across the country, and amazing music, dance, INCREASE theater, and local cuisine at the city’s free welcome-to-summer event. As always we are grateful to the Mayor, Columbus in website traffic City Council and the Ohio Arts Council for our funding and all the individuals, corporations and community aided by Google partners who support our work in the arts. AD GRANT PROGRAM Tom Katzenmeyer David Clifton President & CEO Board Chair arts>sports that of Columbus Nonprofit arts attendance home game sports Additional support from: The Crane Group and The Sol Morton and Dorothy Isaac, in Columbus is attendance Rebecca J. -

Smart Logistics Electrification Rural Mobility Flyohio City Solutions

Rural Mobility FlyOhio Electrification Smart Logistics City Solutions Table of Contents Letter from the Director .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Focus on Safety ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Smart Mobility in Ohio ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Unmanned Aerial Systems .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Electrification ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.3. Smart Logistics ............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.4. City Solutions................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.5. Rural Mobility Solutions ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT for COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements the PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE the PACT TEAM President E

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT FOR COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements THE PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE THE PACT TEAM President E. Gordon Gee, The Ohio State University Tim Anderson, Resident, In My Backyard Health and Wellness Program Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director Mayor Michael B. Coleman, City of Columbus Lela Boykin, Woodland Park Civic Association Autumn Williams, Program Director Charles Hillman, President & CEO, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority Bryan Brown, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) Penney Letrud, Administration & Communications Assistant (CMHA) Willis Brown, Bronzeville Neighborhood Association Dr. Steven Gabbe, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Reverend Cynthia Burse, Bethany Presbyterian Church THE PLANNING TEAM Goody Clancy Barbara Cunningham, Poindexter Village Resident Council OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE ACP Visioning + Planning Al Edmondson, Business Owner, Mt. Vernon Avenue District Improvement Fred Ransier, Chair, PACT Association Community Research Partners Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director, PACT Jerry Friedman, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Skilken Solutions Jerry Friedman, Associate Vice President, Health Services, Ohio State Wexner Columbus Policy Works Medical Center Shannon Hardin, City of Columbus Radio One Tony Brown Consulting Elizabeth Seely, Executive Director, University Hospital East Eddie Harrell, Columbus Urban League Troy Enterprises Boyce Safford, Former Director of Development, City of Columbus Stephanie Hightower, Neighborhood -

Performance Measurement Plan (Pfmp) for the Smart Columbus Demonstration Program

Performance Measurement Plan (PfMP) for the Smart Columbus Demonstration Program FINAL REPORT | June 2019 Produced by City of Columbus Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because it is essential to the contents of the work. Acknowledgment of Support This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation under Agreement No. DTFH6116H00013. Disclaimer Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the Author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Acknowledgments The Smart Columbus Program would like to thank project leads and local stakeholders for each of the Smart Columbus projects for their assistance in drafting and reviewing this Smart Columbus Performance Measurement Plan. Performance Measurement Plan (PfMP) – Final Report | Smart Columbus Program | i Abstract This Performance Measurement Plan describes the outcomes of Smart Columbus and how the objectives of each of projects relate to them. The plan identifies and explains the methodology proposed to evaluate the indicators for each project, which will provide insight into the performance of a project in meeting the objectives. The plan also describes the data necessary to evaluate the objectives and the required reporting frequency and contents. The responsibilities and types of interactions between the City of Columbus and an independent evaluator are also described. -

COC Celebrateone 2019-20 Annual Report V14.Indd

2019-2020 COMMUNITY IMPACT ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CELEBRATEONE GOVERNING BOARD Dr. Mysheika Roberts, Chair Health Commissioner, Columbus Public Health Karen Morrison, Vice-Chair President, OhioHealth Foundation and Senior Vice President, OhioHealth Stephanie Hightower, Treasurer President and CEO, Columbus Urban League Erik Janas, Secretary Deputy County Administrator, Franklin County Board of Commissioners Cathy Lyttle, Immediate Past Chair Senior Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer, Worthington Industries Teddy Ceasar Pastor, Destiny Church International Dan Crane Vice President, Crane Group Tracy Davidson CEO, United Healthcare Honorable Andrew J. Ginther Mayor, City of Columbus Rebecca Howard Parent What’s Inside... Timothy C. Robinson CEO, Nationwide Children's Hospital Maureen Stapleton Executive Director, CelebrateOne, Letter from Mayor Ginther & Board Chair Dr. Roberts ............................................................................4 ex-officio and non-voting Letter from the Executive Director ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Then and Now: Community Impact ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 One of the most profound and One Mom’s Story ...........................................................................................................................................7 heartbreaking impacts of systemic racism and poverty is the loss of our Then: Our Evolution -

20-24 Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan

Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report | Report Number 20-24 | August 2020 NYSERDA Department of Transportation Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report Prepared for: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority New York, NY Robyn Marquis Project Manager and New York State Department of Transportation Albany, NY Mark Grainer Joseph Buffamonte, Region 5 Project Managers Prepared by: Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. & WSP USA Inc. Buffalo, New York NYSERDA Report 20-24 NYSERDA Contract 112009 August 2020 NYSDOT Project No. C-17-55 Notice This report was prepared by Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. in coordination with WSP USA Inc., in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (hereafter “NYSERDA”). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of NYSERDA or the State of New York, and reference to any specific product, service, process, or method does not constitute an implied or expressed recommendation or endorsement of it. Further, NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no warranties or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any product, apparatus, or service, or the usefulness, completeness, or accuracy of any processes, methods, or other information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no representation that the use of any product, apparatus, process, method, or other information will not infringe privately owned rights and will assume no liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from, or occurring in connection with, the use of information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. -

Northland I Area Plan

NORTHLAND I AREA PLAN COLUMBUS PLANNING DIVISION ADOPTED: This document supersedes prior planning guidance for the area, including the 2001 Northland Plan-Volume I and the 1992 Northland Development Standards. (The Northland Development Standards will still be applicable to the Northland II planning area until the time that plan is updated.) Cover Photo: The Alum Creek Trail crosses Alum Creek at Strawberry Farms Park. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Columbus City Council Northland Community Council Development Committee Andrew J. Ginther, President Albany Park Homeowners Association Rolling Ridge Sub Homeowners Association Herceal F. Craig Lynn Thurman Rick Cashman Zachary M. Klein Blendon Chase Condominium Association Salem Civic Association A. Troy Miller Allen Wiant Brandon Boos Michelle M. Mills Eileen Y. Paley Blendon Woods Civic Association Sharon Woods Civic Association Priscilla R. Tyson Jeanne Barrett Barb Shepard Development Commission Brandywine Meadows Civic Association Strawberry Farms Civic Association Josh Hewitt Theresa Van Davis Michael J. Fitzpatrick, Chair John A. Ingwersen, Vice Chair Cooperwoods Condominium Association Tanager Woods Civic Association Marty Anderson Alicia Ward Robert Smith Maria Manta Conroy Forest Park Civic Association Village at Preston Woods Condo Association John A. Cooley Dave Paul John Ludwig Kay Onwukwe Stefanie Coe Friendship Village Residents Association Westerville Woods Civic Association Don Brown Gerry O’Neil Department of Development Karmel Woodward Park Civic Association Woodstream East Civic Association Steve Schoeny, Director William Logan Dan Pearse Nichole Brandon, Deputy Director Bill Webster, Deputy Director Maize/Morse Tri-Area Civic Association Advisory Member Christine Ryan Mark Bell Planning Division Minerva Park Advisory Member Vince Papsidero, AICP, Administrator (Mayor) Lynn Eisentrout Bob Thurman Kevin Wheeler, Assistant Administrator Mark Dravillas, AICP, Neighborhood Planning Manager Northland Alliance Inc. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to lielp you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated vwth a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large dieet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Bulletin #20 May 15, 2021

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #20 May 15, 2021 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, May 15, 2021 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (Legislation was signed by Council President Pro Tem Elizabeth Brown on, Tuesday, May 11, 2021; by Mayor, Andrew J. Ginther on Wednesday, May 12, 2021; with the exception of Ord. 1094-2021 which was signed by Mayor Ginther on May 11, 2021 and attested by the City Clerk on May 12, 2021, all other legislation was attested by the Acting City Clerk prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 05/15/21) 2 of 343 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 05/15/21) 3 of 343 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH 43215-9015 Minutes - Final columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council Monday, May 10, 2021 5:00 PM City Council Chambers, Rm 231 REGULAR MEETING NO. -

Letter from the President

VARSITY O 2019 FALL NEWS LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Fellow Varsity O Members, Happy Fall! Autumn officially means many things: students back on The Ohio State campus, the crisp air with crunchy leaves beneath each step, our fall-sport Buckeyes taking their respective fields and courts, Saturdays in The SHOE, and… Varsity O’s most exciting time of year! In early September, we celebrated our 42nd year of The Ohio State University Athletics Hall of Fame. Our incredible inductees were legends in their sport, Olympic medalists, international icons, and can I just say, “Amazing human beings that were fun, kind, humble, and gracious to be awarded with such prestige!” As we roll into October, I want to remind all of you of our Homecoming Tailgate which will be at the French Fieldhouse on October 5th from 4-7pm prior to the Michigan State game. This is a great opportunity to join Varsity O and fellow Buckeyes for a food buffet, cash-bar, music, corn-hole, photo booth, and other fun surprises we have planned. We will also be celebrating our Jim Jones Career Achievement Award and Varsity O Loyalty award winners as well! Through the 2019-2020 academic year, the University is celebrating its storied and proud history of 150 years. We are calling it, “The Sesquicentennial Year of Celebration”. And although our Athletic Department does not date quite that far back, certainly the contributions and traditions of OSU Athletics has played a storied role in the history of the BEST university in the country. Since the earliest days, OSU athletes have inspired millions across the globe, and have delivered some of the most historic and thrilling moments in collegiate sports. -

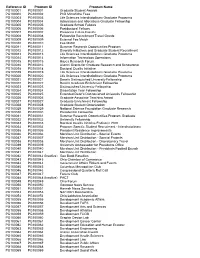

Program FDM Values

Reference ID Program ID Program Name PG100001 PG100001 Graduate Student Awards PG100002 PG100002 PhD Microfiche Fees PG100003 PG100003 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100004 PG100004 Admissions and Allocations Graduate Fellowship PG100005 PG100005 Graduate School Fellows PG100006 PG100006 Postdoctoral Fellows PG100007 PG100007 Preparing Future Faculty PG100008 PG100008 Fellowship Recruitment Travel Grants PG100009 PG100009 External Fee Match PG100010 PG100010 Fee Match PG100011 PG100011 Summer Research Opportunities Program PG100012 PG100012 Diversity Initiatives and Graduate Student Recruitment PG100013 PG100013 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100014 PG100014 Information Technology Operations PG100015 PG100015 Hayes Research Forum PG100016 PG100016 Alumni Grants for Graduate Research and Scholarship PG100018 PG100018 Doctoral Quality Initiative PG100019 PG100019 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100020 PG100020 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100021 PG100021 Dean's Distinguished University Fellowship PG100022 PG100022 Dean's Graduate Enrichment Fellowship PG100023 PG100023 Distinguished University Fellowship PG100024 PG100024 Dissertation Year Fellowship PG100025 PG100025 Extended Dean's Distinguished University Fellowship PG100026 PG100026 Graduate Associate Teaching Award PG100027 PG100027 Graduate Enrichment Fellowship PG100028 PG100028 Graduate Student Organization PG100029 PG100029 National Science Foundation Graduate Research PG100030 PG100030 Presidential