Panorama: the Thatcher Interviews and the NHS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Thomson CV

James Thomson Sound Recordist / mixer e-mail: [email protected] mobile: + 44 (0)7711 031 615 Nationality: Canadian and British passports ( no I Visa required for working in the USA ) Bases: West Hampstead, London & Clifton, Bristol Languages: English / conversational French Diary service: Jane Murch at Films at 59 + 44 ( 0)117 906 4334 Credits - Documentary Fred and Rose West the Untold Story - Blink Films for ITV Studios, directed by Adam Kaleta Drive to Survive F1 - Box to Box Productions for Netflix TV, directed by James Gay-Rees Push the Global Housing Crisis - WG Films / Malmo Inc for Netflix TV, directed by Fredrik Gertten The English Surgeon - Storyville for BBC TV, directed by Geoffrey Smith with music by Nick Cave Keith Richards X-Pensive Winos - Main Offender Tour, directed by the late Roger Pomphrey The Musicals - with Neil Brand, 3 X 1hrs for BBC 4, directed by Sebastian Barfield Sachin A Billion Dreams - docudrama Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, directed by James Erskine The Murder Detectives - Films of Record Productions for Channel 4, directed by Bart Corpe Britain and the Sea - with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by John Hodgson Nazi Mega Stuctures - Darlow-Smithson for Nat Geo, directed by Simon Breen All Change at Longleat - Shine Productions, BBC 1, directed by Lynn Alleyway Origins of Us - with Dr. Alice Roberts, BBC TV, directed by David Stewart A Picture of Britain – with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by Jonty Claypool Magritte - The life of surrealist painter Rene Magritte for Channel 4, directed by Michael Burke Omnibus - Bernardo Bertolucci & ‘The Dreamers’, BBC TV, directed by David Thompson Race Across America with James Cracknell for Discovery USA, directed by Andrew Barron The Great British Paraorchestra for Channel 4, directed by Cesca Eaton The Vanishing Family - Channel 4, directed by Richard Bond D-Day - Dangerous Productions for BBC TV, directed by Richard Dale James May’s 20th Century, BBC TV, directed by Helen Thomas Churchill’s Forgotten Years – BBC TV, directed by Russell Barnes Ultimate Swarms with Dr. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department Of

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature The Passive in the British Political News Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Written by: Mgr. Renata Jančaříková, Ph.D. Karolína Šafářová Announcement I hereby declare that I have worked on this thesis independently and that I have used only the sources from the works cited list. Brno, 30 March 2017 ..…..………………… Karolína Šafářová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Jančaříková, Ph.D, for her guidance, kind support and valuable advice. Anotace Tato bakalářská práce The Passive in the British political news je zaměřena na užití trpného rodu v politických článcích na téma Brexit vyskytujících se v seriozních novinách The Guardian a bulváru The Daily Mail. V práci je použita kvantitatvní analýza za účelem srovnání výskytu činného a trpného rodu, vyhodnocení důvodů pro používání trpného rodu, analyzování výskytu významových a uvozovacích sloves, a poměru činitelů trpného rodu vyjádřených pomocí 'by'. Annotation This bachelor thesis The Passive in the British political news is focused on the use of the passive in the broadsheet The Guardian and the tabloid The Daily Mail on the topic of concerning Brexit. It uses quantitative analysis to compare the frequency of use of the active and the passive voice, to analyze reasons for using the passive, the frequency of occurrence of lexical and report verbs, and the proportion of agents expressed by 'by'. Klíčová slova trpný rod, činný rod, noviny, politické zprávy, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, analýza, kvalitní noviny, bulvár Key Words passive voice, active voice, newspaper, political news, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, analysis broadsheets, tabloids Content 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

Piers Morgan Outrage Over Brandpool Celebrity Trust Survey Submitted By: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010

Piers Morgan outrage over Brandpool celebrity trust survey Submitted by: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010 Piers Morgan has expressed outrage at being voted the sixth least trusted celebrity brand ambassador in a survey by ad agency and creative content providers Brandpool. Writing in his Mail On Sunday column, the Britain’s Got Talent judge questioned the logic of the poll, which named the celebrities the public would most and least trust as the faces of an ad campaign. But Brandpool has hit back at Morgan for failing to recognise the purpose of its research. Morgan, who also neglected to credit Brandpool as the source of the study, said: “No real surprises on the Most Trusted list, which is led by ‘national treasures’ such as David Attenborough, Stephen Fry, Richard Branson and Michael Parkinson. “As for the Least Trusted list, I find the logic of this one quite odd. Katie Price, for example, comes top, yet I would argue that she’s one of the most trustworthy people I know… Then I suddenly pop up at No 6, an outrage which perhaps only I feel incensed about. Particularly as that smiley little rodent Russell Brand slithers in at No 7. Making me supposedly less trustworthy than a former heroin junkie and sex addict.” Morgan was also surprised to see Simon Cowell, Cheryl Cole, Sharon Osbourne, Tom Cruise and Jonathan Ross in the Least Trusted list. However, he agreed with the inclusion of John Terry, Ashley Cole, Tiger Woods and Tony Blair, all of whom, he said, were “united by a common forked tongue”. -

June 2014 Newsletter

D M A Newsletter June 2014 Editorial David M Riches Welcome to the June 2014 Newsletter. Thanks to our contributors I think we have another interesting newsletter that I hope you will find informative and enjoy reading. I’m always amazed at the variety of activities the museums in Dorset are engaged in. One of the beauties of visiting museums is that no two are the same, nor even similar. As some of you may already know, one of my other interests is vintage and antique scientific instruments, which I personally collect. I belong to an organisation called the Scientific Instrument Society and each year they hold two study tours, an overseas one in the spring and a shorter one, usually in Britain, in the autumn. By the time you read this I will probably be in Switzerland on the first of these this year visiting a variety of museums and CERN. However, the autumn tour this year will be to Dorset. I am organising it and over the three days from 17th to 19th October they will be visiting the Dorset Clock & Cider Museum, the BNSS, The Royal Signals Museum and the Water Museum at Sutton Poyntz, before finishing at Weymouth Museum where there will be a viewing and handling session of part of my collection. Sadly, I had also planned a visit to the Museum of Electricity which is now closed, as this had a good collection of electrical instruments amongst its impressive collection of electrical equipment and machinery. Hopefully this tour will encourage some of the members to visit Dorset and its museums again. -

The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education

Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume one, number one April 2012 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 1 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Mick Temple, Staffordshire University Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Jenny McKay Sunderland University Stuart Allan, Bournemouth University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, Rhodes University Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, Bedfordshire University Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Irish press ombudsman. Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, Brunel University Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, University -

Where Next for the (Broadcast) Political Interview? David Dimbleby Looks Back and Forward

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2014/10/18/where-next-for-the-broadcast-political-interview-david-dimbleby-looks-back-and-forward/ Where next for the (broadcast) political interview? David Dimbleby looks back and forward It all went wrong with the introduction of the sofa. Once politicians had the option of a cozy chat with comfy pillows, then the gladiatorial combat of the traditional broadcast interview was dead. The other David, Frost on the sofa with Mrs Thatcher That is the core message from David Dimbleby’s thoughtful lecture on the art of the political interview, given to celebrate the 90th birthday of the psephology legend Sir David Butler. The BBC recorded it so you will be able to judge for yourself, but listening in St Peter’s Chapel, Oxford along with a selection of broadcasting’s great and not so good, I realised just how much the form has changed and wondered whether it is now effectively dead. Newsnight editor Ian Katz has written an intelligent and progressive analysis of the crisis of the TV political interview. He suggests that to revive it politicians and journalists need to agree to a more relaxed, slightly less adversarial approach where the politicians are allowed to stray beyond the soundbites and indulge in thinking aloud without the journalist jumping on any phrase that does not fit precisely with the party line. Time, says Katz, is of the essence. Even a 5-7 minutes Newsnight (or Today programme) interview is not enough to get past the posturing. Dimbleby agrees with Katz that size matters. -

Sir David Attenborough Trounces Young Stars in Brandpool's Celebrity Trust Poll

Sir David Attenborough trounces young stars in Brandpool’s celebrity trust poll Submitted by: Friday's Media Group Friday, 9 April 2010 Sir David Attenborough trounces young stars in Brandpool’s celebrity trust poll Sir David Attenborough is the celebrity consumers would most trust as the figurehead for an advertising campaign, according to a survey commissioned by ad agency and creative content providers Brandpool. However, it was Katie Price who narrowly beat John Terry and Ashley Cole to be voted the least believable brand ambassador, followed by Amy Winehouse, Heather Mills, Tiger Woods and Tony Blair – the latter raising questions over Labour’s deployment of its former leader as a ‘secret weapon’ in the run-up to the election. The survey flies in the face of the Cebra study published last week by research agency Millward Brown, which indexed the appeal of celebrities in relation to certain brands. But Brandpool’s research suggests the popularity of young stars such as David Tennant, Cheryl Cole and David Beckham doesn’t always translate into trust. The poll saw 46% of respondents name Sir David as one of their top three choices, with Stephen Fry second on 36% and Richard Branson third on 20%. It was the elder statesmen of British broadcasting who dominated the top 10, with Michael Parkinson, Sir Terry Wogan, Sir David Dimbleby, Jeremy Paxman, Lord Alan Sugar and Jeremy Clarkson also highly rated. These silver-haired stars were favoured despite almost a third of respondents being under 35. And although an even split of men and women voted, the only female celebrity in the top 10 was The One Show presenter Christine Bleakley. -

Facultade De Filoloxía Grao En Lingua E Literatura

Facultade de Filoloxía Grao en Lingua e Literatura Inglesas Traballo de Fin de Grao A Study on The Crown : History and Fiction about the Historical Figure of Queen Elizabeth II Graduanda: Miriam Ariadna Grande Izquierdo Titora: Dra. Cristina Mourón Figueroa Curso académico: 2018/2019 Table of Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. The Making of The Crown 5 3. Facts vs. Fiction 12 4. Conclusions 32 5. Bibliography and Electronic Resources 36 6. Appendix 43 UIIIV H UAD 1f: S TIAGO DE COMPOSTELA FACULTADE DE FILOLOXfA ' 1 \ 1 u 1, \t ttLL\LJl Ul. I IL . •LO\L\ í ~ w ~ '1 ENTRADA N~."·" · ····················-········ Formulario de delimitación de tftulo e resumo Traballo de Fin de Grao curso 2018/ 2019 APWDOS E NOME: G r ~ndc lrqulerdo, Mirlam Ariadna GAAO EN : Lencua v htrr<t \Uti) Inglesas (NO CASO DE MODERNAS) MENCIÓN EN: TITORA: Crist1na Mour6n Figueroa UFl A TEMATICA ASIGNADA: Historia e cultura das lila~ Brítáni<as SOLICITO a aprobación do segulnte titulo e resumo: Titulo: A Study on T~ Crown: Hlstory and Flctlon about the Hlstorfcal Figure of Qu een Ell :zabeth 11 Resumo [na lingua en que se vai redactar o TFG; entre 1000 e 2000 caracteres): This dissertatíon intends to be a study on the relevance of the figure of the present Queen of the United K!ngdom, Ellzabeth 11, by focuslng on the hlstorical and social clrcumstances wh ich marked the flrst period of her long reign as is portrayed in the Netflix original TV series The Crown (created by Peter Morgan in 2016 and still runmng). -

Ben Newth AMPS Head of Audio

Ben Newth AMPS Head of Audio 1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA 44-48 Bloomsbury Street, London, WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama Cyberbully - RTS and BAFTA Nominee 'Best Single Drama' 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 The People Next Door 1 x 60' RAW TV for Channel 4 UKIP: The First 100 Days 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 Blackout 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 American Blackout 1 x 90’ RAW TV for National Geographic Hard Tide 1 x 90' Deerstalker Films Blackbird - BAFTA Scotland Nominee 'Audience Award' 1 x 90’ Deerstalker Films Mermaids 1 x 90’ Darlow Smithson for Animal Planet I Shouldn’t Be Alive 14 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for Animal Planet & ITV Playhouse Presents: The Call Out 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts Drijfzand 1 x 90' Pieter van Huistee for NED Ticket to Jerusalem 1 x 90' Argus Films Ford Transit 1 x 90' Augustus Films Comedy The Life of Rock with Brian Pern 2 x 30' BBC Comedy for BBC Two Boom Town 6 x 30' Knickerbockerglory for BBC Three A Bear's Tale 6 x 30' Bellyache Productions for Channel 4 Documentary: Factual Heathrow: Britain's Busiest Airport 2 x 50' RAW TV for ITV Alex Jones: Fertility and Me 1 x 60' BBC Scotland for BBC One Celebrity Troll Trackers 1 x 50' Popkorn for C5 Dr Jeff: Rocky Mountain Vet 6 x 60' Double Act for Discovery Miss Transgender UK 1 x 60' Minnow Films for BBC Three and BBC One Body Hack: Metal Gear Man 2 x 15' BBC Three Rest in Pixels 1 x 30' BBC Three Stephen Fry in Central America 3 x -

Model Decision Notice and Advice

Reference: FS50150782 Freedom of Information Act 2000 (Section 50) Decision Notice Date: 25 March 2008 Public Authority: British Broadcasting Corporation (‘BBC’) Address: MC3 D1 Media Centre Media Village 201 Wood Lane London W12 7TQ Summary The complainant requested details of payments made by the BBC to a range of personalities, actors, journalists and broadcasters. The BBC refused to provide the information on the basis that the information was held for the purposes of journalism, art and literature. Having considered the purposes for which this information is held, the Commissioner has concluded that the requested information was not held for the dominant purposes of journalism, art and literature and therefore the request falls within the scope of the Act. Therefore the Commissioner has decided that in responding to the request the BBC failed to comply with its obligations under section 1(1). Also, in failing to provide the complainant with a refusal notice the Commissioner has decided that the BBC breached section 17(1) of the Act. However, the Commissioner has also concluded that the requested information is exempt from disclosure by virtue of section 40(2) of the Act. The Commissioner’s Role 1. The Commissioner’s duty is to decide whether a request for information made to a public authority has been dealt with in accordance with the requirements of Part 1 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (the “Act”). In the particular circumstances of this complaint, this duty also includes making a formal decision on whether the BBC is a public authority with regard to the information requested by the complainant. -

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists June 2006 NOT FOR PUBLICATION BEFORE 00.01 HOURS THURSDAY JUNE 15TH 2006 1 Foreword by Sir Peter Lampl In a number of recent studies the Sutton Trust has highlighted the predominance of those from private schools in the country’s leading and high profile professions1. In law, we found that almost 70% of barristers in the top chambers had attended fee-paying schools, and, more worryingly, that the young partners in so called ‘magic circle’ law firms were now more likely than their equivalents of 20 years ago to have been independently-educated. In politics, we showed that one third of MPs had attended independent schools, and this rose to 42% among those holding most power in the main political parties. Now, with this study, we have found that leading news and current affairs journalists – those figures who are so central in shaping public opinion and national debate – are more likely than not to have been to independent schools which educate just 7% of the population. Of the top 100 journalists in 2006, 54% were independently educated an increase from 49% in 1986. Not only does this say something about the state of our education system, but it also raises questions about the nature of the media’s relationship with society: is it healthy that those who are most influential in determining and interpreting the news agenda have educational backgrounds that are so different to the vast majority of the population? What is clear is that an independent school education offers a tremendous boost to the life chances of young people, making it more likely that they will attain highly in school exams, attend the country’s leading universities and gain access to the highest and most prestigious professions. -

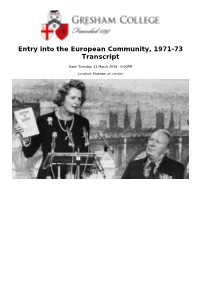

Entry Into the European Community, 1971-73 Transcript

Entry into the European Community, 1971-73 Transcript Date: Tuesday, 11 March 2014 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 11 MARCH 2014 ENTRY INTO THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, 1971-73 PROFESSOR VERNON BOGDANOR Ladies and gentlemen, this is the fourth of a series of lectures on Britain and Europe since 1945, and this lecture will describe how Britain finally entered the European Community, as the European Union was then known, in 1973, after two failed attempts. One of the remarkable features of the 1970s is that the political alignments and attitudes of the parties towards Europe were almost exactly opposite to what they are today. Today, the most sympathetic of the two major parties towards Europe is the Labour Party – they are broadly pro-European. But the main party of the right, the Conservatives, are divided and predominantly Euro-sceptic. In the 1970s, by contrast, it was the opposite. The Conservatives, under the leadership of Edward Heath, the most pro-European Prime Minister we have ever had, were the Euro-enthusiasts. Now, just 40 years ago, in March 1974, Heath resigned as Prime Minister, having narrowly lost a General Election in which Europe was a major issue, and he was replaced by Labour’s Harold Wilson as Prime Minister of a Minority Government. One year after that, in 1975, Heath lost the Conservative leadership to Margaret Thatcher, but she too began as a Euro-enthusiast, continuing to support the European Union. She became a Euro-sceptic much later than is usually imagined. Conservative pro-Europeanism extended then even to Conservative-supporting newspapers.