Journal of Metaphysics and Ontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charity and Error-Theoretic Nominalism Hemsideversion

Published in Ratio 28 (3), pp. 256-270, DOI: 10.1111/rati.12070 CHARITY AND ERROR-THEORETIC NOMINALISM Arvid Båve Abstract I here investigate whether there is any version of the principle of charity both strong enough to conflict with an error-theoretic version of nominalism about abstract objects (EN), and supported by the considerations adduced in favour of interpretive charity in the literature. I argue that in order to be strong enough, the principle, which I call “(Charity)”, would have to read, “For all expressions e, an acceptable interpretation must make true a sufficiently high ratio of accepted sentences containing e”. I next consider arguments based on (i) Davidson’s intuitive cases for interpretive charity, (ii) the reliability of perceptual beliefs, and (iii) the reliability of “non-abstractive inference modes”, and conclude that none support (Charity). I then propose a diagnosis of the view that there must be some universal principle of charity ruling out (EN). Finally, I present a reason to think (Charity) is false, namely, that it seems to exclude the possibility of such disagreements as that between nominalists and realists. Nominalists about abstract objects have given remarkably disparate answers to the question: how, if there are no abstract objects, should we view statements that seem to involve purported reference to or quantification over such objects?1 According to the 1 I define nominalism as the view not merely that there are no abstract objects, but also that nothing is an abstract object, contra certain “noneists” like Graham Priest (2005), who accept the Arvid Båve error-theoretic variant of nominalism (EN), these statements should be taken at face value, both semantically and pragmatically, i.e., taken both as literally entailing that there are abstract objects, and also as used and interpreted literally by ordinary speakers. -

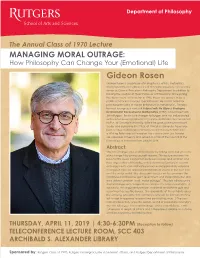

Gideon Rosen Gideon Rosen Is a Professor of Metaphysics, Ethics, Metaethics, and Philosophy of Mathematics at Princeton University

Department of Philosophy The Annual Class of 1970 Lecture MANAGING MORAL OUTRAGE: How Philosophy Can Change Your (Emotional) Life Gideon Rosen Gideon Rosen is a professor of metaphysics, ethics, metaethics, and philosophy of mathematics at Princeton University. He currently serves as Chair of Princeton’s Philosophy Department in addition to holding the position of Stuart Professor of Philosophy. Since joining the department at Princeton in 1993, Rosen has proved to be a prolific scholar in his various specializations. He is most noted for proposing the idea of modal fictionalism in metaphysics. Perhaps his most recognized work is A Subject with No Object: Strategies for Nominalist Reconstrual in Mathematics (1997), coauthored with John Burgess. Rosen is no stranger to Rutgers and has collaborated with various Rutgers professors on papers and books. He completed his B.A. at Columbia University, where he graduated summa cum laude, and completed his Ph.D. at Princeton University. Rosen has held a Hauser Fellowship in Global Law at NYU Law School and a Whiting Fellowship at Princeton. He is also a John Jay Scholar via Columbia University and served as Chair of the Council of the Humanities at Princeton from 2006 to 2014. Abstract: You can change your emotional state by taking a pill, but you can also change it by giving yourself reasons. This lecture explores the basis for this deep connection between reason and emotion and then argues that philosophy, with its distinctive battery of reasons and arguments, can motivate pervasive and potentially valuable changes in how we respond emotionally to events in our own lives and the wider world. -

Mark Schroeder [email protected] 3709 Trousdale Parkway Markschroeder.Net

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ USC School of Philosophy 323.632.8757 (mobile) Mudd Hall of Philosophy Mark Schroeder [email protected] 3709 Trousdale Parkway markschroeder.net Los Angeles, CA 90089-0451 Curriculum Vitae philosophy.academy ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Ph.D., Philosophy, Princeton University, November 2004, supervised by Gideon Rosen M.A., Philosophy, Princeton University, November 2002 B.A., magna cum laude, Philosophy, Mathematics, and Economics, Carleton College, June 2000 EMPLOYMENT University of Southern California, Professor since December 2011 previously Assistant Professor 8/06 – 4/08, Associate Professor with tenure 4/08 – 12/11 University of Maryland at College Park, Instructor 8/04 – 1/05, Assistant Professor 1/05 – 6/06 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ RESEARCH INTERESTS My research has focused primarily on metaethics, practical reason, and related areas, particularly including normative ethics, philosophy of language, epistemology, philosophy of mind, metaphysics, the philosophy of action, agency, and responsibility, and the history of ethics. HONORS AND AWARDS Elected to USC chapter of Phi Kappa Phi, 2020; 2017 Phi Kappa Phi Faculty -

"Fictionalism: Morality and Metaphor"

- 1 - Fictionalism: Morality and metaphor Richard Joyce Penultimate draft of paper appearing in F. Kroon & B. Armour-Garb (eds.), Philosophical Fictionalism (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). 1. Introduction Language and reflection often pull against each other. Ordinary ways of talking appear to commit speakers to ontologies that may, upon reflection, be deemed problematic for a variety of empirical, metaphysical, and/or epistemological reasons. The use of moral discourse, for example, appears to commit speakers to the existence of obligation, evil, desert, praiseworthiness (and so on), while metaethical reflection raises a host of doubts about how such properties could exist in the world and how we could have access to them if they did. One extreme solution to the tension is to give up reflection—to become like those “honest gentlemen” of England, as Hume described them, who “being always employ’d in domestic affairs, or amusing themselves in common recreations, have carried their thoughts very little beyond those objects” (Treatise 1.4.7.14). Hume sounds a touch envious of the unreflective idyll, but the very fact that he is penning a treatise on human nature shows that this is not a solution available to him; and, likewise, the very fact that you are reading this chapter shows that it’s unlikely to be a solution for you. Another extreme solution to the tension is to give up language—not in toto, of course, but selectively: to stop using those elements of discourse that are deemed to have unacceptable commitments. How radical this eliminativism is will depend on the nature of the problem. -

THE THEORY of MATHEMATICAL SUBTRACTION in ARISTOTLE By

THE THEORY OF MATHEMATICAL SUBTRACTION IN ARISTOTLE by Ksenia Romashova Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2019 © Copyright by Ksenia Romashova, 2019 DEDICATION PAGE To my Mother, Vera Romashova Мама, Спасибо тебе за твою бесконечную поддержку, дорогая! ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED ....................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 2 THE MEANING OF ABSTRACTION .............................................................. 6 2.1 Etymology and Evolution of the Term ................................................................... 7 2.2 The Standard Phrase τὰ ἐξ ἀφαιρέσεως or ‘Abstract Objects’ ............................ 19 CHAPTER 3 GENERAL APPLICATION OF ABSTRACTION .......................................... 24 3.1 The Instances of Aphairein in Plato’s Dialogues ................................................. 24 3.2 The Use of Aphairein in Aristotle’s Topics -

Quantified Modality and Essentialism

Quantified Modality and Essentialism Saul A. Kripke This is the accepted version of the following article: Kripke, S. A. (2017), Quantified Modality and Essentialism. Noûs, 51: 221-234. doi: 10.1111/nous.12126, Which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12126. 1 Quantified Modality and Essentialism1 Saul A. Kripke It is well know that the most thoroughgoing critique of modal logic has been that of W.V. Quine. Quine’s position, though uniformly critical of quantified modal systems, has nevertheless varied through the years from extreme and flat rejection of modality to a more nearly moderate critique. At times Quine urged that, for purely logico-semantical reasons based on the problem of interpreting quantified modalities, a quantified modal logic is impossible; or, alternatively, that it is possible only on the basis of a queer ontology which repudiates the individuals of the concrete world in favor of their ethereal intensions. Quine has also urged that even if these objections have been answered, modal logic would clearly commit itself to the metaphysical jungle of Aristotelian essentialism; and this essentialism is held to be a notion far more obscure than the notion of analyticity upon which modal logic was originally to be based. 1 There is a long story behind this paper. It was written for a seminar given by Quine himself in the academic year 1961/2, and discussed in class over a period of several weeks. Some years later, I was surprised to hear from Héctor-Neri Castañeda that it had received wider circulation among philosophers. -

Obscurantism in Social Sciences

Diogenes http://dio.sagepub.com/ Hard and Soft Obscurantism in the Humanities and Social Sciences Jon Elster Diogenes 2011 58: 159 DOI: 10.1177/0392192112444984 The online version of this article can be found at: http://dio.sagepub.com/content/58/1-2/159 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: International Council for Philosophy and Human Studiess Additional services and information for Diogenes can be found at: Email Alerts: http://dio.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://dio.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://dio.sagepub.com/content/58/1-2/159.refs.html >> Version of Record - Jul 11, 2012 What is This? Downloaded from dio.sagepub.com at Kings College London - ISS on November 3, 2013 Article DIOGENES Diogenes 58(1–2) 159–170 Hard and Soft Obscurantism in the Copyright Ó ICPHS 2012 Reprints and permission: Humanities and Social Sciences sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0392192112444984 dio.sagepub.com Jon Elster Colle`ge de France Scholarship is a risky activity, in which there is always the possibility of failure. Many scholars fail honorably, and sometimes tragically, if they have devoted their career to pursuing an hypoth- esis that was finally disproved. The topic of this article is dishonorable failures. In other words, the thrust of the argument will be overwhelmingly negative.1 I shall argue that there are many schools of thought in the humanities and the social sciences that are obscurantist, by which I mean that one can say ahead of time that pursuits within these paradigms are unlikely to yield anything of value. -

Why Essentialism Requires Two Senses of Necessity’, Ratio 19 (2006): 77–91

Please cite the official published version of this article: ‘Why Essentialism Requires Two Senses of Necessity’, Ratio 19 (2006): 77–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9329.2006.00310.x WHY ESSENTIALISM REQUIRES TWO SENSES OF NECESSITY1 Stephen K. McLeod Abstract I set up a dilemma, concerning metaphysical modality de re, for the essentialist opponent of a ‘two senses’ view of necessity. I focus specifically on Frank Jackson’s two- dimensional account in his From Metaphysics to Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998). I set out the background to Jackson’s conception of conceptual analysis and his rejection of a two senses view. I proceed to outline two purportedly objective (as opposed to epistemic) differences between metaphysical and logical necessity. I conclude that since one of these differences must hold and since each requires the adoption of a two senses view of necessity, essentialism is not consistent with the rejection of a two senses view. I. Terminological Preliminaries The essentialist holds that some but not all of a concrete object’s properties are had necessarily and that necessary properties include properties that are, unlike the property 1 Thanks to John Divers, audiences at the Open University Regional Centre, Leeds and the University of Glasgow and an anonymous referee for comments. 2 of being such that logical and mathematical truths hold, non-trivially necessary. It is a necessary condition on a property’s being essential to an object that it is had of necessity. In the case of concrete objects, some such properties are discoverable by partly empirical means. -

Continuity and Mathematical Ontology in Aristotle

Journal of Ancient Philosophy, vol. 14 issue 1, 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.1981-9471.v14i1p30-61 Continuity and Mathematical Ontology in Aristotle Keren Wilson Shatalov In this paper I argue that Aristotle’s understanding of mathematical continuity constrains the mathematical ontology he can consistently hold. On my reading, Aristotle can only be a mathematical abstractionist of a certain sort. To show this, I first present an analysis of Aristotle’s notion of continuity by bringing together texts from his Metaphysica and Physica, to show that continuity is, for Aristotle, a certain kind of per se unity, and that upon this rests his distinction between continuity and contiguity. Next I argue briefly that Aristotle intends for his discussion of continuity to apply to pure mathematical objects such as lines and figures, as well as to extended bodies. I show that this leads him to a difficulty, for it does not at first appear that the distinction between continuity and contiguity can be preserved for abstract mathematicals. Finally, I present a solution according to which Aristotle’s understanding of continuity can only be saved if he holds a certain kind of mathematical ontology. My topic in this paper is Aristotle’s understanding of mathematical continuity. While the idea that continua are composed of infinitely many points is the present day orthodoxy, the Aristotelian understanding of continua as non-punctiform and infinitely divisible was the reigning theory for much of the history of western mathematics, and there is renewed interest in it from current mathematicians and philosophers of mathematics. -

Burns* (Skidmore College)

Klesis – Revue philosophique – 2011 : 19 – Autour de Leo Strauss Leo Strauss’s Life and Work Timothy Burns* (Skidmore College) I. Life Leo Strauss (1899-1973) was a German-born American political philosopher of Jewish heritage who revived the study of political philosophy in the 20 th century. His complex philosophical reflections exercise a quietly growing, deep influence in America, Europe, and Asia. Strauss was born in the rural town of Kirchhain in Hesse-Nassau, Prussia, on September 20, 1899, to Hugo and Jenny David Strauss. He attended Kirchhain’s Volksschule and the Rektoratsschule before enrolling, in 1912, at the Gymnasium Philippinum in Marburg, graduating in 1917. The adolescent Strauss was immersed in Hermann Cohen’s neo-Kantianism, the most progressive German-Jewish thinking. “Cohen,” Strauss states, “was the center of attraction for philosophically minded Jews who were devoted to Judaism.” After serving in the German army for a year and a half, Strauss began attending the University at Marburg, where he met Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jacob Klein. In 1921 he went to Hamburg, where he wrote his doctoral thesis under Ernst Cassirer. In 1922, Strauss went to the University of Freiburg-im-Breisgau for a post- doctoral year, in order to see and hear Edmund Husserl, but he also attended lecture courses given by Martin Heidegger. He participated in Franz Rosenzweig’s Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus in Frankfurt-am-Main, and published articles in Der Jude and the Jüdische Rundschau . One of these articles, on Cohen’s analysis of Spinoza, brought Strauss to the attention of Julius Guttmann, who in 1925 offered him a position researching Jewish Philosophy at the Akademie für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin. -

On Categories and a Posteriori Necessity: a Phenomenological Echo

© 2012 The Author Metaphilosophy © 2012 Metaphilosophy LLC and Blackwell Publishing Ltd Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK, and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA METAPHILOSOPHY Vol. 43, Nos. 1–2, January 2012 0026-1068 ON CATEGORIES AND A POSTERIORI NECESSITY: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ECHO M. J. GARCIA-ENCINAS Abstract: This article argues for two related theses. First, it defends a general thesis: any kind of necessity, including metaphysical necessity, can only be known a priori. Second, however, it also argues that the sort of a priori involved in modal metaphysical knowledge is not related to imagination or any sort of so-called epistemic possibility. Imagination is neither a proof of possibility nor a limit to necessity. Rather, modal metaphysical knowledge is built on intuition of philo- sophical categories and the structures they form. Keywords: a priori, categories, intuition, metaphysical necessity. Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters. —Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), The Caprices, plate 43, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters 1. Introduction Statements of fact are necessarily true when their truth-maker facts cannot but be the case. Statements of fact are contingently true when their truth-maker facts might not have been the case. I shall argue that modal knowledge, that is, knowledge that a (true/false) statement is necessarily/ contingently true, must be a priori knowledge, even if knowledge that the statement is true or false can be a posteriori. In particular, justified accept- ance of necessary facts requires a priori modal insight concerning some category which they instantiate. In this introduction, the first part of the article, I maintain that Kripke claimed that the knowledge that a statement has its truth-value as a matter of necessity/contingency is a priori founded—even when knowl- edge of its truth/falsehood is a posteriori. -

Berkeley's Case Against Realism About Dynamics

Lisa Downing [Published in Berkeley’s Metaphysics, ed. Muehlmann, Penn State Press 1995, 197-214. Turbayne Essay Prize winner, 1992.] Berkeley's case against realism about dynamics While De Motu, Berkeley's treatise on the philosophical foundations of mechanics, has frequently been cited for the surprisingly modern ring of certain of its passages, it has not often been taken as seriously as Berkeley hoped it would be. Even A.A. Luce, in his editor's introduction to De Motu, describes it as a modest work, of limited scope. Luce writes: The De Motu is written in good, correct Latin, but in construction and balance the workmanship falls below Berkeley's usual standards. The title is ambitious for so brief a tract, and may lead the reader to expect a more sustained argument than he will find. A more modest title, say Motion without Matter, would fitly describe its scope and content. Regarded as a treatise on motion in general, it is a slight and disappointing work; but viewed from a narrower angle, it is of absorbing interest and high importance. It is the application of immaterialism to contemporary problems of motion, and should be read as such. ...apart from the Principles the De Motu would be nonsense.1 1The Works of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, ed. A.A. Luce and T.E. Jessop (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1948-57), 4: 3-4. In this paper, all references to Berkeley are to the Luce-Jessop edition. Quotations from De Motu are taken from Luce's translation. I use the following abbreviations for Berkeley’s works: PC Philosophical Commentaries PHK-I Introduction to The Principles of Human Knowledge PHK The Principles of Human Knowledge DM De Motu A Alciphron TVV The Theory of Vision Vindicated and Explained S Siris 1 There are good general reasons to think, however, that Berkeley's aims in writing the book were as ambitious as the title he chose.