NGC-6826 (Caldwell 15) the Blinking Planetary in Cygnus Introduction the Purpose of the Observer’S Challenge Is to Encourage the Pursuit of Visual Observing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection an Addition To: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection An addition to: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag. PSA Observation Notes: Chart RA Dec Chart 1) Date Time 2 Equipment) 3) Notes # Observing Notes # Sgr M24 The Sagittarias Star Cloud 1. Mag 4.60 RA 18:16.5 Dec -18:50 Distance: 10.0 2. (kly)Star cloud, 95’ x 35’, Small Sagittarius star cloud 3. lies a little over 7 degrees north of teapot lid. Look for 7,8 dark Lanes! Wealth of stars. M24 has dark nebula 67 (interstellar dust – often visible in the infrared (cooler radiation)). Barnard 92 – near the edge northwest – oval in shape. Ref: Celestial Sampler Floating on Cloud 24, p.112 Sgr M18 - 1. RA 18 19.9, Dec -17.08 Distance: 4.9 (kly) 2. Lies less than 1deg above the northern edge of M24. 3 8 Often bypassed by showy neighbours, it is visible as a 67 small hazy patch. Note it's much closer (1/2 the distance) as compared to M24 (10kly) Sgr M17 (Swan Nebula) and M16 – HII region 1. Nebula and Open Clusters 2. 8 67 M17 Wikipedia 3. Ref: Celestial Sampler p. 113 Sct M11 Wild Duck Cluster 5.80 1. 18:51.1 -06:16 Distance: 6.0 (kly) 2. Open cluster, 13’, You can find the “wild duck” cluster, 3. as Admiral Smyth called it, nearly three degrees west of 67 8 Aquila’s beak lying in one of the densest parts of the summer Milky Way: the Scutum Star Cloud. 9 64 10 Vul M27 Dumbbell Nebula 1. -

Catalogue of Excitation Classes P for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae

Catalogue of Excitation Classes p for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae Name p Name p Name p Name p NeC 40 1 Nee 6072 9 NeC 6881 10 IC 4663 11 NeC 246 12+ Nee 6153 3 NeC 6884 7 IC 4673 10 NeC 650-1 10 Nee 6210 4 NeC 6886 9 IC 4699 9 NeC 1360 12 Nee 6302 10 Nee 6891 4 IC 4732 5 NeC 1501 10 Nee 6309 10 NeC 6894 10 IC 4776 2 NeC 1514 8 NeC 6326 9 Nee 6905 11 IC 4846 3 NeC 1535 8 Nee 6337 11 Nee 7008 11 IC 4997 8 NeC 2022 12 Nee 6369 4 NeC 7009 7 IC 5117 6 NeC 2242 12+ NeC 6439 8 NeC 7026 9 IC 5148-50 6 NeC 2346 9 NeC 6445 10 Nee 7027 11 IC 5217 6 NeC 2371-2 12 Nee 6537 11 Nee 7048 11 Al 1 NeC 2392 10 NeC 6543 5 Nee 7094 12 A2 10 NeC 2438 10 NeC 6563 8 NeC 7139 9 A4 10 NeC 2440 10 NeC 6565 7 NeC 7293 7 A 12 4 NeC 2452 10 NeC 6567 4 Nee 7354 10 A 15 12+ NeC 2610 12 NeC 6572 7 NeC 7662 10 A 20 12+ NeC 2792 11 NeC 6578 2 Ie 289 12 A 21 1 NeC 2818 11 NeC 6620 8 IC 351 10 A 23 4 NeC 2867 9 NeC 6629 5 Ie 418 1 A 24 1 NeC 2899 10 Nee 6644 7 IC 972 10 A 30 12+ NeC 3132 9 NeC 6720 10 IC 1295 10 A 33 11 NeC 3195 9 NeC 6741 9 IC 1297 9 A 35 1 NeC 3211 10 NeC 6751 9 Ie 1454 10 A 36 12+ NeC 3242 9 Nee 6765 10 IC1747 9 A 40 2 NeC 3587 8 NeC 6772 9 IC 2003 10 A 41 1 NeC 3699 9 NeC 6778 9 IC 2149 2 A 43 2 NeC 3918 9 NeC 6781 8 IC 2165 10 A 46 2 NeC 4071 11 NeC 6790 4 IC 2448 9 A 49 4 NeC 4361 12+ NeC 6803 5 IC 2501 3 A 50 10 NeC 5189 10 NeC 6804 12 IC 2553 8 A 51 12 NeC 5307 9 NeC 6807 4 IC 2621 9 A 54 12 NeC 5315 2 NeC 6818 10 Ie 3568 3 A 55 4 NeC 5873 10 NeC 6826 11 Ie 4191 6 A 57 3 NeC 5882 6 NeC 6833 2 Ie 4406 4 A 60 2 NeC 5879 12 NeC 6842 2 IC 4593 6 A -

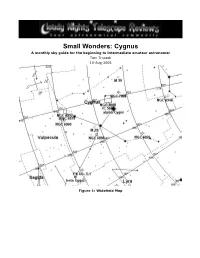

Cygnus a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005

Small Wonders: Cygnus A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005 Figure 1: Widefield Map 2/16 Small Wonders: Cygnus Target List Object Type Size Mag RA Dec α (alpha) Cygni (Deneb) Star 1.3 20h 41m 38.7s 45 17' 59" β (beta) Cygni (Albireo) Star 3 19h 30m 57.9s 27 58' 18" NGC 7000 Bright Nebula 120.0'x100.0' 4 20h 59m 03.2s 44 32' 16" IC 5070 Bright Nebula 60.0'x50.0' 8 20h 51m 01.1s 44 12' 13" NGC 6960 Supernova Remnant 70.0'x6.0' 7 20h 45m 57.0s 30 44' 12" NGC 6979 Bright Nebula 7.0'x3.0' 20h 51m 14.9s 32 10' 14" NGC 6992 Bright Nebula 60.0'x8.0' 7 20h 56m 39.0s 31 44' 16" M 29 Open Cluster 10.0' 6.6 20h 24m 11.6s 38 30' 58" M 39 Open Cluster 31.0' 4.6 21h 32m 10.4s 48 26' 40" NGC 6826 Planetary Nebula 36" 8.8 19h 44m 58.8s 50 32' 21" NGC 7026 Planetary Nebula 45" 10.9 21h 06m 31.4s 47 52' 28" NGC 6888 Bright Nebula 18.0'x13.0' 10 20h 12m 20.0s 38 22' 18" NGC 6946 Galaxy 11.5'x9.8' 9 20h 35m 01.0s 60 10' 19" Challenge Objects Object Type Size Mag RA Dec PK 64+ 5.1 Planetary Nebula 5" 9.6 19h 35m 02.3s 30 31' 45" Sh2-112 9.0'x7.0' Cygnus ygnus is a spectacular summer constellation. -

TIMOTHY BARKER^ ~2 Unclas

The Ionization Structure of Planetary Nebulae VIII. NGC 6826 TIMOTHY BARKER^ ~2 Department of Physics and Astronomy Wheaton College Received (hASA-CR-180142) THE ICNJZA'IICti STRUCTUHE b87- 175 81 OF PLANETARY IEEULAE. E: LJGC tE26 (Wheatcn CCfl.) 34 p CSCL 03A Unclas G3/84 43731 'Visiting Astronomer, Kitt Peak National Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatories, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under contract with the National Science Foundation. 2Guest observer with the International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite, NASA grant NSG 5376. - L$~DL..J,-~~/~'-~ , I , Page 2 ABSTRACT Spectrophotometric observations of emission-line intensities over the spectral range 1400-7200 A have been made in seven positions in the planetary nebula NGC 6826. The O++ electron temperature varies little from 8900 K throughout the nebula; the Balmer continuum electron temperature averages 1500 K higher. The h4267 C I1 line intensities imply C++ abundances that are systematically higher than those determined from the h1906, 1909 C I111 lines, but because of uncertainties in the intensities of the UV lines relative to the optical ones, this discrepancy is less conclusively demonstrated in NGC 6826 thad in other planetaries in this series. Standard equations used to correct for the existence of elements in other than the optically observable ionization stages give results that are consistent and also in approximate agreement with abundances calculated using ultraviolet lines in the few cases where the relevant ultraviolet lines are measurable. The logarithmic abundances (relative to H=12.00) are: Hem10.97, 008.60, N07.71, Nez7.96, C08.53, Ars6.11, and S=6.77. -

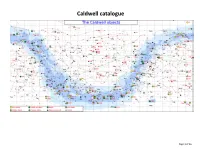

Caldwell Catalogue - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Caldwell catalogue - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Caldwell catalogue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents The Caldwell Catalogue is an astronomical catalog of 109 bright star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies for observation by amateur astronomers. The list was compiled Featured content by Sir Patrick Caldwell-Moore, better known as Patrick Moore, as a complement to the Messier Catalogue. Current events The Messier Catalogue is used frequently by amateur astronomers as a list of interesting deep-sky objects for observations, but Moore noted that the list did not include Random article many of the sky's brightest deep-sky objects, including the Hyades, the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884), and NGC 253. Moreover, Moore observed that the Donate to Wikipedia Messier Catalogue, which was compiled based on observations in the Northern Hemisphere, excluded bright deep-sky objects visible in the Southern Hemisphere such [1][2] Interaction as Omega Centauri, Centaurus A, the Jewel Box, and 47 Tucanae. He quickly compiled a list of 109 objects (to match the number of objects in the Messier [3] Help Catalogue) and published it in Sky & Telescope in December 1995. About Wikipedia Since its publication, the catalogue has grown in popularity and usage within the amateur astronomical community. Small compilation errors in the original 1995 version Community portal of the list have since been corrected. Unusually, Moore used one of his surnames to name the list, and the catalogue adopts "C" numbers to rename objects with more Recent changes common designations.[4] Contact Wikipedia As stated above, the list was compiled from objects already identified by professional astronomers and commonly observed by amateur astronomers. -

The Caldwell Catalogue+Photos

The Caldwell Catalogue was compiled in 1995 by Sir Patrick Moore. He has said he started it for fun because he had some spare time after finishing writing up his latest observations of Mars. He looked at some nebulae, including the ones Charles Messier had not listed in his catalogue. Messier was only interested in listing those objects which he thought could be confused for the comets, he also only listed objects viewable from where he observed from in the Northern hemisphere. Moore's catalogue extends into the Southern hemisphere. Having completed it in a few hours, he sent it off to the Sky & Telescope magazine thinking it would amuse them. They published it in December 1995. Since then, the list has grown in popularity and use throughout the amateur astronomy community. Obviously Moore couldn't use 'M' as a prefix for the objects, so seeing as his surname is actually Caldwell-Moore he used C, and thus also known as the Caldwell catalogue. http://www.12dstring.me.uk/caldwelllistform.php Caldwell NGC Type Distance Apparent Picture Number Number Magnitude C1 NGC 188 Open Cluster 4.8 kly +8.1 C2 NGC 40 Planetary Nebula 3.5 kly +11.4 C3 NGC 4236 Galaxy 7000 kly +9.7 C4 NGC 7023 Open Cluster 1.4 kly +7.0 C5 NGC 0 Galaxy 13000 kly +9.2 C6 NGC 6543 Planetary Nebula 3 kly +8.1 C7 NGC 2403 Galaxy 14000 kly +8.4 C8 NGC 559 Open Cluster 3.7 kly +9.5 C9 NGC 0 Nebula 2.8 kly +0.0 C10 NGC 663 Open Cluster 7.2 kly +7.1 C11 NGC 7635 Nebula 7.1 kly +11.0 C12 NGC 6946 Galaxy 18000 kly +8.9 C13 NGC 457 Open Cluster 9 kly +6.4 C14 NGC 869 Open Cluster -

NGC-6826 (Caldwell 15), the Blinking Planetary Introduction the Purpose of the Observer’S Challenge Is to Encourage the Pursuit of Visual Observing

MONTHLY OBSERVER’S CHALLENGE Las Vegas Astronomical Society Compiled by: Roger Ivester, Boiling Springs, North Carolina & Fred Rayworth, Las Vegas, Nevada With special assistance from: Rob Lambert, Las Vegas, Nevada Summer Supplemental 2010 NGC-6826 (Caldwell 15), the Blinking Planetary Introduction The purpose of the observer’s challenge is to encourage the pursuit of visual observing. It is open to everyone that is interested, and if you are able to contribute notes, drawings, or photographs, we will be happy to include them in our monthly summary. Observing is not only a pleasure, but an art. With the main focus of amateur astronomy on astrophotography, many times people tend to forget how it was in the days before cameras, clock drives, and GOTO. Astronomy depended on what was seen through the eyepiece. Not only did it satisfy an innate curiosity, but it allowed the first astronomers to discover the beauty and the wonderment of the night sky. Before photography, all observations depended on what the astronomer saw in the eyepiece, and how they recorded their observations. This was done through notes and drawings and that is the tradition we are stressing in the observers challenge. By combining our visual observations with our drawings, and sometimes, astrophotography (from those with the equipment and talent to do so), we get a unique understanding of what it is like to look through an eyepiece, and to see what is really there. The hope is that you will read through these notes and become inspired to take more time at the eyepiece studying each object, and looking for those subtle details that you might never have noticed before. -

January 2013

El Gordo January 2013 This young galaxy cluster, nicknamed “El Gordo” for the “big” or S M T W Th F Sa “fat” one in Spanish, is a remarkable object. Found about 7.2 bil - 1 2 3 4 5 lion light years away, El Gordo appears to be the most massive, hottest, and most powerful X-ray emitter of any known cluster at its 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 distance or beyond. In this composite image, X-rays are blue, opti - 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 cal data from the Very Large Telescope are red, green, and blue, and infrared emission from Spitzer is red. The comet-like shape of 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 the X-rays, along with optical data, shows that El Gordo is actually two galaxy clusters in the process of colliding at several million 27 28 29 30 31 miles per hour. NGC 3627 February 2013 NGC 3627 is a spiral galaxy located about 30 million light years S M T W Th F Sa from Earth. A survey of 62 galaxies with Chandra revealed that 1 2 many of these galaxies contained supermassive black holes that previously were undetected. This study showed the value of X-ray 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 observations for finding central black holes that have relatively low- 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 er masses, as is the case for NGC 3627. This composite image of NGC 3627 includes data from Chandra (blue), Spitzer (red), as well 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 as optical data from Hubble and the Very Large Telescope (yellow). -

Institute for Astronomy University of Hawai'i at M¯Anoa Publications in Calendar Year 2013

Institute for Astronomy University of Hawai‘i at Manoa¯ Publications in Calendar Year 2013 Aberasturi, M., Burgasser, A. J., Mora, A., Reid, I. N., Barnes, J. E., & Privon, G. C. Experiments with IDEN- Looper, D., Solano, E., & Mart´ın, E. L. Hubble Space TIKIT. In ASP Conf. Ser. 477: Galaxy Mergers in an Telescope WFC3 Observations of L and T dwarfs. Evolving Universe, 89–96 (2013) Mem. Soc. Astron. Italiana, 84, 939 (2013) Batalha, N. M., et al., including Howard, A. W. Planetary Albrecht, S., Winn, J. N., Marcy, G. W., Howard, A. W., Candidates Observed by Kepler. III. Analysis of the First Isaacson, H., & Johnson, J. A. Low Stellar Obliquities in 16 Months of Data. ApJS, 204, 24 (2013) Compact Multiplanet Systems. ApJ, 771, 11 (2013) Bauer, J. M., et al., including Meech, K. J. Centaurs and Scat- Al-Haddad, N., et al., including Roussev, I. I. Magnetic Field tered Disk Objects in the Thermal Infrared: Analysis of Configuration Models and Reconstruction Methods for WISE/NEOWISE Observations. ApJ, 773, 22 (2013) Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejections. Sol. Phys., 284, Baugh, P., King, J. R., Deliyannis, C. P., & Boesgaard, A. M. 129–149 (2013) A Spectroscopic Analysis of the Eclipsing Short-Period Aller, K. M., Kraus, A. L., & Liu, M. C. A Pan-STARRS + Binary V505 Persei and the Origin of the Lithium Dip. UKIDSS Search for Young, Wide Planetary-Mass Com- PASP, 125, 753–758 (2013) panions in Upper Sco. Mem. Soc. Astron. Italiana, 84, Beaumont, C. N., Offner, S. S. R., Shetty, R., Glover, 1038–1040 (2013) S. C. -

Number of Objects by Type in the Caldwell Catalogue

Caldwell catalogue Page 1 of 16 Number of objects by type in the Caldwell catalogue Dark nebulae 1 Nebulae 9 Planetary Nebulae 13 Galaxy 35 Open Clusters 25 Supernova remnant 2 Globular clusters 18 Open Clusters and Nebulae 6 Total 109 Caldwell objects Key Star cluster Nebula Galaxy Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C22 NGC 7662 Blue Snowball Planetary Nebula 3.2 Andromeda 9 C23 NGC 891 Galaxy 31,000 Andromeda 10 C28 NGC 752 Open Cluster 1.2 Andromeda 5.7 C107 NGC 6101 Globular Cluster 49.9 Apus 9.3 Page 2 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C55 NGC 7009 Saturn Nebula Planetary Nebula 1.4 Aquarius 8 C63 NGC 7293 Helix Nebula Planetary Nebula 0.522 Aquarius 7.3 C81 NGC 6352 Globular Cluster 18.6 Ara 8.2 C82 NGC 6193 Open Cluster 4.3 Ara 5.2 C86 NGC 6397 Globular Cluster 7.5 Ara 5.7 Flaming Star C31 IC 405 Nebula 1.6 Auriga - Nebula C45 NGC 5248 Galaxy 74,000 Boötes 10.2 Page 3 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C5 IC 342 Galaxy 13,000 Camelopardalis 9 C7 NGC 2403 Galaxy 14,000 Camelopardalis 8.4 C48 NGC 2775 Galaxy 55,000 Cancer 10.3 C21 NGC 4449 Galaxy 10,000 Canes Venatici 9.4 C26 NGC 4244 Galaxy 10,000 Canes Venatici 10.2 C29 NGC 5005 Galaxy 69,000 Canes Venatici 9.8 C32 NGC 4631 Whale Galaxy Galaxy 22,000 Canes Venatici 9.3 Page 4 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation -

Stellar Wind Models of Central Stars of Planetary Nebulae J

A&A 635, A173 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937150 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics Stellar wind models of central stars of planetary nebulae J. Krtickaˇ 1, J. Kubát2, and I. Krtickovᡠ1 1 Ústav teoretické fyziky a astrofyziky, Masarykova univerzita, Kotlárskᡠ2, 611, 37 Brno, Czech Republic e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomický ústav, Akademie vedˇ Ceskéˇ republiky, Fricovaˇ 298, 251 65 Ondrejov,ˇ Czech Republic Received 20 November 2019 / Accepted 26 February 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Fast line-driven stellar winds play an important role in the evolution of planetary nebulae, even though they are relatively weak. Aims. We provide global (unified) hot star wind models of central stars of planetary nebulae. The models predict wind structure including the mass-loss rates, terminal velocities, and emergent fluxes from basic stellar parameters. Methods. We applied our wind code for parameters corresponding to evolutionary stages between the asymptotic giant branch and white dwarf phases for a star with a final mass of 0:569 M . We study the influence of metallicity and wind inhomogeneities (clumping) on the wind properties. Results. Line-driven winds appear very early after the star leaves the asymptotic giant branch (at the latest for T 10 kK) and eff ≈ fade away at the white dwarf cooling track (below Teff = 105 kK). Their mass-loss rate mostly scales with the stellar luminosity and, consequently, the mass-loss rate only varies slightly during the transition from the red to the blue part of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. There are the following two exceptions to the monotonic behavior: a bistability jump at around 20 kK, where the mass- loss rate decreases by a factor of a few (during evolution) due to a change in iron ionization, and an additional maximum at about 1 1 Teff = 40 50 kK.