January 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galaxy Clusters: Waking Perseus

PUBLISHED: 2 JUNE 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 164 news & views GALAXY CLUSTERS Waking Perseus The Perseus cluster contains over 1,000 a Kelvin–Helmholtz instability, which galaxies packed into a region ~3,500 kpc propagates in the wave direction and in extent. It is inevitable that such close- causes the dark area indicated in the packed galaxies will interact, and the image. This dark ‘bay-like’ feature is Chandra X-ray Observatory has observed approximately the size of the Milky Way, the beautiful result of that interaction and may be the result of a cold front in (pictured). This is no snapshot — the cluster gas: an interface where the Chandra observed the galaxy cluster temperature drops dramatically on scales for over 16 days in order to capture this much smaller than the mean free path. image. Stephen Walker and colleagues An advantage of this comparison of have retrieved the archival data and observations and simulations is that processed it to enhance the edges of (unmeasurable) physical quantities the surface brightness distribution. This can be estimated. In this case, the bay analysis, reported last year (Sanders et al., 50 kpc feature only appears in this form when Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 460, 1898–1911; the ratio of the thermal pressure to the ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY ASTRONOMICAL ROYAL 2016), highlighted two features in the magnetic pressure is ~200, and this X-ray emission that are discussed by determination in turn allows the authors Walker et al. (Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. pattern seen in the image could have been to obtain an order-of-magnitude estimate 468, 2506–2516; 2017): the swirling wave generated by a passing galaxy cluster about of the magnetic field. -

Formation of the Active Star Forming Region LHA 120-N 44 Triggered By

Draft version December 24, 2018 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX61 FORMATION OF THE ACTIVE STAR FORMING REGION LHA 120-N 44 TRIGGERED BY TIDALLY-DRIVEN COLLIDING HI FLOWS Kisetsu Tsuge,1 Hidetoshi Sano,1,2 Kengo Tachihara,1 Cameron Yozin,3 Kenji Bekki,3 Tsuyoshi Inoue,1 Norikazu Mizuno,4 Akiko Kawamura,4 Toshikazu Onishi,5 and Yasuo Fukui1,2 1Department of Physics, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan; [email protected] 2Institute for Advanced Research, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan 3ICRAR, M468, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley Western Australia 6009, Australia 4National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan 5Department of Physical Science, Graduate School of Science, Osaka Prefecture University, 1-1 Gakuen-cho, Naka-ku, Sakai, Osaka 599-8531, Japan (Accepted November 30, 2018) ABSTRACT N44 is the second active site of high mass star formation next to R136 in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). We carried out a detailed analysis of Hi at 60 arcsec resolution by using the ATCA & Parkes data. We presented decomposition of the Hi emission into two velocity components (the L- and D-components) with the velocity separation of ∼60 km s−1. In addition, we newly defined the I-component whose velocity is intermediate between the L- and D-components. The D-component was used to derive the rotation curve of the LMC disk, which is consistent with the stellar rotation curve (Alves & Nelson 2000). Toward the active cluster forming region of LHA 120-N 44, the three velocity components of Hi gas show signatures of dynamical interaction including bridges and complementary spatial distributions. -

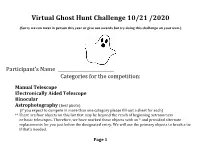

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

The Dynamical State of the Coma Cluster with XMM-Newton?

A&A 400, 811–821 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021911 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics The dynamical state of the Coma cluster with XMM-Newton? D. M. Neumann1,D.H.Lumb2,G.W.Pratt1, and U. G. Briel3 1 CEA/DSM/DAPNIA Saclay, Service d’Astrophysique, L’Orme des Merisiers, Bˆat. 709, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 2 Science Payloads Technology Division, Research and Science Support Dept., ESTEC, Postbus 299 Keplerlaan 1, 2200AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands 3 Max-Planck Institut f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr., 85740 Garching, Germany Received 19 June 2002 / Accepted 13 December 2002 Abstract. We present in this paper a substructure and spectroimaging study of the Coma cluster of galaxies based on XMM- Newton data. XMM-Newton performed a mosaic of observations of Coma to ensure a large coverage of the cluster. We add the different pointings together and fit elliptical beta-models to the data. We subtract the cluster models from the data and look for residuals, which can be interpreted as substructure. We find several significant structures: the well-known subgroup connected to NGC 4839 in the South-West of the cluster, and another substructure located between NGC 4839 and the centre of the Coma cluster. Constructing a hardness ratio image, which can be used as a temperature map, we see that in front of this new structure the temperature is significantly increased (higher or equal 10 keV). We interpret this temperature enhancement as the result of heating as this structure falls onto the Coma cluster. We furthermore reconfirm the filament-like structure South-East of the cluster centre. -

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection an Addition To: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection An addition to: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag. PSA Observation Notes: Chart RA Dec Chart 1) Date Time 2 Equipment) 3) Notes # Observing Notes # Sgr M24 The Sagittarias Star Cloud 1. Mag 4.60 RA 18:16.5 Dec -18:50 Distance: 10.0 2. (kly)Star cloud, 95’ x 35’, Small Sagittarius star cloud 3. lies a little over 7 degrees north of teapot lid. Look for 7,8 dark Lanes! Wealth of stars. M24 has dark nebula 67 (interstellar dust – often visible in the infrared (cooler radiation)). Barnard 92 – near the edge northwest – oval in shape. Ref: Celestial Sampler Floating on Cloud 24, p.112 Sgr M18 - 1. RA 18 19.9, Dec -17.08 Distance: 4.9 (kly) 2. Lies less than 1deg above the northern edge of M24. 3 8 Often bypassed by showy neighbours, it is visible as a 67 small hazy patch. Note it's much closer (1/2 the distance) as compared to M24 (10kly) Sgr M17 (Swan Nebula) and M16 – HII region 1. Nebula and Open Clusters 2. 8 67 M17 Wikipedia 3. Ref: Celestial Sampler p. 113 Sct M11 Wild Duck Cluster 5.80 1. 18:51.1 -06:16 Distance: 6.0 (kly) 2. Open cluster, 13’, You can find the “wild duck” cluster, 3. as Admiral Smyth called it, nearly three degrees west of 67 8 Aquila’s beak lying in one of the densest parts of the summer Milky Way: the Scutum Star Cloud. 9 64 10 Vul M27 Dumbbell Nebula 1. -

MC^ 2: Galaxy Imaging and Redshift Analysis of the Merging Cluster CIZA J2242. 8+ 5301

LLNL-DOC-661846-DRAFT A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 8/13/10 MC2: GALAXY IMAGING AND REDSHIFT ANALYSIS OF THE MERGING CLUSTER CIZA J2242.8+5301 William A. Dawson1, M. James Jee2, Andra Stroe3, Y. Karen Ng2, Nathan Golovich2, David Wittman2, David Sobral3,4,5, M. Bruggen¨ 6, H. J. A. Rottgering¨ 3, R. J. van Weeren7 (Dated: Draft June 21, 2021) LLNL-DOC-661846-DRAFT ABSTRACT X-ray and radio observations of CIZA J2242.8+5301 suggest that it is a major cluster merger. Despite being well studied in the X-ray, and radio, little has been presented on the cluster structure and dynamics inferred from its galaxy population. We carried out a deep (i< 25) broad band imaging survey of the system with Subaru SuprimeCam (g & i bands) and the Canada France Hawaii Telescope (r band) as well as a comprehensive spectroscopic survey of the cluster area (505 redshifts) using Keck DEIMOS. We use this data to perform a comprehensive galaxy/redshift analysis of the system, which is the first step to a proper understanding the geometry and dynamics of the merger, as well as using the merger to constrain self-interacting dark matter. We find that the system is dominated by two ′+0.7 +0.13 subclusters of comparable richness with a projected separation of6.9 −0.5 (1.3−0.10 Mpc). We find that the north and south subclusters have similar redshifts of z 0.188 with a relative line-of-sight velocity difference of 69 190kms−1. We also find that north and south≈ subclusters have velocity dispersions of +100 −±1 +100 −1 +4.6 14 1160−90 kms and 1080−70 kms , respectively. -

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) are we still here? Today’s Topics • “How do we know?” exercise • Size and Scale • What is the Universe made of? • How big are these things? • How do they compare to each other? • How can we organize objects to make sense of them? What is the Universe made of? Stars • Stars make up the vast majority of the visible mass of the Universe • A star is a large, glowing ball of gas that generates heat and light through nuclear fusion • Our Sun is a star Planets • According to the IAU, a planet is an object that 1. orbits a star 2. has sufficient self-gravity to make it round 3. has a mass below the minimum mass to trigger nuclear fusion 4. has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit • A dwarf planet (such as Pluto) fulfills all these definitions except 4 • Planets shine by reflected light • Planets may be rocky, icy, or gaseous in composition. Moons, Asteroids, and Comets • Moons (or satellites) are objects that orbit a planet • An asteroid is a relatively small and rocky object that orbits a star • A comet is a relatively small and icy object that orbits a star Solar (Star) System • A solar (star) system consists of a star and all the material that orbits it, including its planets and their moons Star Clusters • Most stars are found in clusters; there are two main types • Open clusters consist of a few thousand stars and are young (1-10 million years old) • Globular clusters are denser collections of 10s-100s of thousand stars, and are older (10-14 billion years -

Catalogue of Excitation Classes P for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae

Catalogue of Excitation Classes p for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae Name p Name p Name p Name p NeC 40 1 Nee 6072 9 NeC 6881 10 IC 4663 11 NeC 246 12+ Nee 6153 3 NeC 6884 7 IC 4673 10 NeC 650-1 10 Nee 6210 4 NeC 6886 9 IC 4699 9 NeC 1360 12 Nee 6302 10 Nee 6891 4 IC 4732 5 NeC 1501 10 Nee 6309 10 NeC 6894 10 IC 4776 2 NeC 1514 8 NeC 6326 9 Nee 6905 11 IC 4846 3 NeC 1535 8 Nee 6337 11 Nee 7008 11 IC 4997 8 NeC 2022 12 Nee 6369 4 NeC 7009 7 IC 5117 6 NeC 2242 12+ NeC 6439 8 NeC 7026 9 IC 5148-50 6 NeC 2346 9 NeC 6445 10 Nee 7027 11 IC 5217 6 NeC 2371-2 12 Nee 6537 11 Nee 7048 11 Al 1 NeC 2392 10 NeC 6543 5 Nee 7094 12 A2 10 NeC 2438 10 NeC 6563 8 NeC 7139 9 A4 10 NeC 2440 10 NeC 6565 7 NeC 7293 7 A 12 4 NeC 2452 10 NeC 6567 4 Nee 7354 10 A 15 12+ NeC 2610 12 NeC 6572 7 NeC 7662 10 A 20 12+ NeC 2792 11 NeC 6578 2 Ie 289 12 A 21 1 NeC 2818 11 NeC 6620 8 IC 351 10 A 23 4 NeC 2867 9 NeC 6629 5 Ie 418 1 A 24 1 NeC 2899 10 Nee 6644 7 IC 972 10 A 30 12+ NeC 3132 9 NeC 6720 10 IC 1295 10 A 33 11 NeC 3195 9 NeC 6741 9 IC 1297 9 A 35 1 NeC 3211 10 NeC 6751 9 Ie 1454 10 A 36 12+ NeC 3242 9 Nee 6765 10 IC1747 9 A 40 2 NeC 3587 8 NeC 6772 9 IC 2003 10 A 41 1 NeC 3699 9 NeC 6778 9 IC 2149 2 A 43 2 NeC 3918 9 NeC 6781 8 IC 2165 10 A 46 2 NeC 4071 11 NeC 6790 4 IC 2448 9 A 49 4 NeC 4361 12+ NeC 6803 5 IC 2501 3 A 50 10 NeC 5189 10 NeC 6804 12 IC 2553 8 A 51 12 NeC 5307 9 NeC 6807 4 IC 2621 9 A 54 12 NeC 5315 2 NeC 6818 10 Ie 3568 3 A 55 4 NeC 5873 10 NeC 6826 11 Ie 4191 6 A 57 3 NeC 5882 6 NeC 6833 2 Ie 4406 4 A 60 2 NeC 5879 12 NeC 6842 2 IC 4593 6 A -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

Constraining Cosmic Rays and Magnetic Fields in the Perseus

A&A 541, A99 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118502 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Constraining cosmic rays and magnetic fields in the Perseus galaxy cluster with TeV observations by the MAGIC telescopes J. Aleksic´1,E.A.Alvarez2, L. A. Antonelli3, P. Antoranz4, M. Asensio2, M. Backes5, U. Barres de Almeida6, J. A. Barrio2, D. Bastieri7, J. Becerra González8,9, W. Bednarek10, A. Berdyugin11,K.Berger8,9,E.Bernardini12, A. Biland13,O.Blanch1,R.K.Bock6, A. Boller13, G. Bonnoli3, D. Borla Tridon6,I.Braun13, T. Bretz14,26, A. Cañellas15,E.Carmona6,28,A.Carosi3,P.Colin6,, E. Colombo8, J. L. Contreras2, J. Cortina1, L. Cossio16, S. Covino3, F. Dazzi16,27,A.DeAngelis16,G.DeCaneva12, E. De Cea del Pozo17,B.DeLotto16, C. Delgado Mendez8,28, A. Diago Ortega8,9,M.Doert5, A. Domínguez18, D. Dominis Prester19,D.Dorner13, M. Doro20, D. Eisenacher14, D. Elsaesser14,D.Ferenc19, M. V. Fonseca2, L. Font20,C.Fruck6,R.J.GarcíaLópez8,9, M. Garczarczyk8, D. Garrido20, G. Giavitto1, N. Godinovic´19,S.R.Gozzini12, D. Hadasch17,D.Häfner6, A. Herrero8,9, D. Hildebrand13, D. Höhne-Mönch14,J.Hose6, D. Hrupec19,T.Jogler6, H. Kellermann6,S.Klepser1, T. Krähenbühl13,J.Krause6, J. Kushida6,A.LaBarbera3,D.Lelas19,E.Leonardo4, N. Lewandowska14, E. Lindfors11, S. Lombardi7,, M. López2, R. López1, A. López-Oramas1,E.Lorenz13,6, M. Makariev21,G.Maneva21, N. Mankuzhiyil16, K. Mannheim14, L. Maraschi3, M. Mariotti7, M. Martínez1,D.Mazin1,6, M. Meucci4, J. M. Miranda4,R.Mirzoyan6, J. Moldón15,A.Moralejo1,P.Munar-Adrover15,A.Niedzwiecki10, D. Nieto2, K. Nilsson11,29,N.Nowak6, R. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93,