Stellar Wind Models of Central Stars of Planetary Nebulae J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Information Bulletin on Variable Stars

COMMISSIONS AND OF THE I A U INFORMATION BULLETIN ON VARIABLE STARS Nos November July EDITORS L SZABADOS K OLAH TECHNICAL EDITOR A HOLL TYPESETTING K ORI ADMINISTRATION Zs KOVARI EDITORIAL BOARD L A BALONA M BREGER E BUDDING M deGROOT E GUINAN D S HALL P HARMANEC M JERZYKIEWICZ K C LEUNG M RODONO N N SAMUS J SMAK C STERKEN Chair H BUDAPEST XI I Box HUNGARY URL httpwwwkonkolyhuIBVSIBVShtml HU ISSN COPYRIGHT NOTICE IBVS is published on b ehalf of the th and nd Commissions of the IAU by the Konkoly Observatory Budap est Hungary Individual issues could b e downloaded for scientic and educational purp oses free of charge Bibliographic information of the recent issues could b e entered to indexing sys tems No IBVS issues may b e stored in a public retrieval system in any form or by any means electronic or otherwise without the prior written p ermission of the publishers Prior written p ermission of the publishers is required for entering IBVS issues to an electronic indexing or bibliographic system to o CONTENTS C STERKEN A JONES B VOS I ZEGELAAR AM van GENDEREN M de GROOT On the Cyclicity of the S Dor Phases in AG Carinae ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: : J BOROVICKA L SAROUNOVA The Period and Lightcurve of NSV ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: :::::::::::::: W LILLER AF JONES A New Very Long Period Variable Star in Norma ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: :::::::::::::::: EA KARITSKAYA VP GORANSKIJ Unusual Fading of V Cygni Cyg X in Early November ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection an Addition To: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection An addition to: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag. PSA Observation Notes: Chart RA Dec Chart 1) Date Time 2 Equipment) 3) Notes # Observing Notes # Sgr M24 The Sagittarias Star Cloud 1. Mag 4.60 RA 18:16.5 Dec -18:50 Distance: 10.0 2. (kly)Star cloud, 95’ x 35’, Small Sagittarius star cloud 3. lies a little over 7 degrees north of teapot lid. Look for 7,8 dark Lanes! Wealth of stars. M24 has dark nebula 67 (interstellar dust – often visible in the infrared (cooler radiation)). Barnard 92 – near the edge northwest – oval in shape. Ref: Celestial Sampler Floating on Cloud 24, p.112 Sgr M18 - 1. RA 18 19.9, Dec -17.08 Distance: 4.9 (kly) 2. Lies less than 1deg above the northern edge of M24. 3 8 Often bypassed by showy neighbours, it is visible as a 67 small hazy patch. Note it's much closer (1/2 the distance) as compared to M24 (10kly) Sgr M17 (Swan Nebula) and M16 – HII region 1. Nebula and Open Clusters 2. 8 67 M17 Wikipedia 3. Ref: Celestial Sampler p. 113 Sct M11 Wild Duck Cluster 5.80 1. 18:51.1 -06:16 Distance: 6.0 (kly) 2. Open cluster, 13’, You can find the “wild duck” cluster, 3. as Admiral Smyth called it, nearly three degrees west of 67 8 Aquila’s beak lying in one of the densest parts of the summer Milky Way: the Scutum Star Cloud. 9 64 10 Vul M27 Dumbbell Nebula 1. -

Binocular Universe

Binocular Universe: Flying High September 2014 Phil Harrington he North America Nebula (NGC 7000) is a large expanse of glowing hydrogen gas mixed with opaque clouds of cosmic dust just 3° east of Deneb [Alpha (α) Cygni] and T 1° to the west of 4th-magnitude Xi (ξ) Cygni. Famous as one of the most luminous blue supergiants visible in the night sky, Deneb marks the tail of Cygnus the Swan, or if you prefer, the top of the Northern Cross asterism. Above: Summer star map from Star Watch by Phil Harrington. Above: Finder chart for this month's Binocular Universe. Chart adapted from Touring the Universe through Binoculars Atlas (TUBA), www.philharrington.net/tuba.htm The North America Nebula epitomizes how observational astronomy has evolved over the years. When he discovered it on October 24, 1786, Sir William Herschel (1738-1822) described the view through his 18.7-inch reflecting telescope as "very large diffused nebulosity, brighter in the middle." Honestly, I am surprised he could see it at all because of his instrument's very narrow field of view. That's one of the biggest challenges to seeing the North America Nebula through a telescope -- it spans an area nearly 2° in diameter. From the sounds of Herschel's notes, the thought of trying to spot it in anything less never crossed his mind. Five score and four years later, the German astronomer Max Wolf became the first to photograph the full span of NGC 7000. Upon seeing his results, he christened it the North America Nebula for its eerie resemblance to that continent. -

CAAC 2018-11.Pdf

Charlotte Amateur Astronomers Club www.charlotteastronomers.org Next Meeting: Friday November 16th, 2018 Time: 7:00 PM Place: Myers Park Baptist Church Education Building – Shalom Hall (Basement) Address: 1900 Queens Road Charlotte, NC 28207 CAAC November 2018 Meeting Appalachian State has had an active astronomy program for about 40 years. The research programs at DSO will be described as well as the Public Outreach program. Our undergraduate and graduate astronomy education activities will also be described. All of these center on state-of-the-art facilities at the off-campus Dark Sky Observatory and the on-campus, roll-off roof, GoTo instructional astronomy lab.All instruments at DSO as well as at the GoTo lab are now controllable from home (DSO) or the adjacent teaching classroom (the GoTo facility). Lots of the details will be of interest to amateurs who can use the same techniques to control their telescopes. Indeed, some of our research programs are within access of equipment and skills possessed by hobbyists. Speaker Dan Caton grew up in Tampa, Florida and attended the University of South Florida, graduating in 1973 with B.A.'s in astronomy and physics. He stayed on to get a Masters in astronomy, and then his Ph.D. in astronomy at Gainesville. After three years of temporary positions, he took a tenure-track position at Appalachian State, where he eventually became a tenured full professor of physics and astronomy, and Director of Observatories. Dan is still there, living in Boone with his wife Susan. His area of expertise is in the study of binary stars. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

Catalogue of Excitation Classes P for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae

Catalogue of Excitation Classes p for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae Name p Name p Name p Name p NeC 40 1 Nee 6072 9 NeC 6881 10 IC 4663 11 NeC 246 12+ Nee 6153 3 NeC 6884 7 IC 4673 10 NeC 650-1 10 Nee 6210 4 NeC 6886 9 IC 4699 9 NeC 1360 12 Nee 6302 10 Nee 6891 4 IC 4732 5 NeC 1501 10 Nee 6309 10 NeC 6894 10 IC 4776 2 NeC 1514 8 NeC 6326 9 Nee 6905 11 IC 4846 3 NeC 1535 8 Nee 6337 11 Nee 7008 11 IC 4997 8 NeC 2022 12 Nee 6369 4 NeC 7009 7 IC 5117 6 NeC 2242 12+ NeC 6439 8 NeC 7026 9 IC 5148-50 6 NeC 2346 9 NeC 6445 10 Nee 7027 11 IC 5217 6 NeC 2371-2 12 Nee 6537 11 Nee 7048 11 Al 1 NeC 2392 10 NeC 6543 5 Nee 7094 12 A2 10 NeC 2438 10 NeC 6563 8 NeC 7139 9 A4 10 NeC 2440 10 NeC 6565 7 NeC 7293 7 A 12 4 NeC 2452 10 NeC 6567 4 Nee 7354 10 A 15 12+ NeC 2610 12 NeC 6572 7 NeC 7662 10 A 20 12+ NeC 2792 11 NeC 6578 2 Ie 289 12 A 21 1 NeC 2818 11 NeC 6620 8 IC 351 10 A 23 4 NeC 2867 9 NeC 6629 5 Ie 418 1 A 24 1 NeC 2899 10 Nee 6644 7 IC 972 10 A 30 12+ NeC 3132 9 NeC 6720 10 IC 1295 10 A 33 11 NeC 3195 9 NeC 6741 9 IC 1297 9 A 35 1 NeC 3211 10 NeC 6751 9 Ie 1454 10 A 36 12+ NeC 3242 9 Nee 6765 10 IC1747 9 A 40 2 NeC 3587 8 NeC 6772 9 IC 2003 10 A 41 1 NeC 3699 9 NeC 6778 9 IC 2149 2 A 43 2 NeC 3918 9 NeC 6781 8 IC 2165 10 A 46 2 NeC 4071 11 NeC 6790 4 IC 2448 9 A 49 4 NeC 4361 12+ NeC 6803 5 IC 2501 3 A 50 10 NeC 5189 10 NeC 6804 12 IC 2553 8 A 51 12 NeC 5307 9 NeC 6807 4 IC 2621 9 A 54 12 NeC 5315 2 NeC 6818 10 Ie 3568 3 A 55 4 NeC 5873 10 NeC 6826 11 Ie 4191 6 A 57 3 NeC 5882 6 NeC 6833 2 Ie 4406 4 A 60 2 NeC 5879 12 NeC 6842 2 IC 4593 6 A -

Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition Completely updated, this Second Edition gives a broad review of astronomical photometry to provide an understanding of astrophysics from a data-based perspective. It explains the underlying principles of the instruments used, and the applications and inferences derived from measurements. Each chapter has been fully revised to account for the latest developments, including the use of CCDs. Highly illustrated, this book provides an overview and historical background of the subject before reviewing the main themes within astronomical photometry. The central chapters focus on the practical design of the instruments and methodology used. The book concludes by discussing specialized topics in stellar astronomy, concentrating on the information that can be derived from the analysis of the light curves of variable stars and close binary systems. This new edition includes numerous bibliographic notes and a glossary of terms. It is ideal for graduate students, academic researchers and advanced amateurs interested in practical and observational astronomy. Edwin Budding is a research fellow at the Carter Observatory, New Zealand, and a visiting professor at the Çanakkale University, Turkey. Osman Demircan is Director of the Ulupınar Observatory of Çanakkale University, Turkey. Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers Today’s professional astronomers must be able to adapt to use telescopes and interpret data at all wavelengths. This series is designed to provide them with a collection of concise, self-contained handbooks, which covers the basic principles peculiar to observing in a particular spectral region, or to using a special technique or type of instrument. The books can be used as an introduction to the subject and as a handy reference for use at the telescope, or in the office. -

Cosmic Raw Material Fig 20-CO, P.438

Stars form in greatStars clouds form of gas in and great dust clouds of gas and dust Slide 1 Cosmic raw material Fig 20-CO, p.438 Chapter Opener The Eagle Nebula (M16) Stars form in great clouds of gas and dust, and this image shows a large region of such cosmic raw material. The gas is visible because, about 2 million years ago, the cloud produced a cluster of bright stars, whose light ionizes the hydrogen gas nearby, causing it to glow. The cluster can be seen just above and to the left of the darker columns of dust at the center of the image. The dark columns or “elephant trunks” of material are seen in much more detail in Figures 20.1 and 20.2. This false-color image was created by combining images taken through filters that select lines of hydrogen alpha (green), oxygen (blue), and sulfur (red). (T.A. Rector, B.A. Wolpa, and OAO/NRAO/AURA/NSF) 1 The Central Region of the Orion Nebula Slide 2 Fig 20-5a, p.443 Figure 20.5 The Central Region of the Orion Nebula The Orion Nebula harbors some of the youngest stars in the solar neighborhood. At the heart of the nebula is the Trapezium cluster, which includes four very bright stars that provide much of the energy that causes the nebula to glow so brightly. In these images, we see a section of the nebula in visible light (left) and infrared (right). The four bright stars in the center of the visible-light image are the Trapezium stars. -

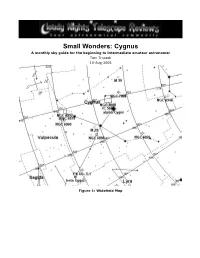

Cygnus a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005

Small Wonders: Cygnus A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005 Figure 1: Widefield Map 2/16 Small Wonders: Cygnus Target List Object Type Size Mag RA Dec α (alpha) Cygni (Deneb) Star 1.3 20h 41m 38.7s 45 17' 59" β (beta) Cygni (Albireo) Star 3 19h 30m 57.9s 27 58' 18" NGC 7000 Bright Nebula 120.0'x100.0' 4 20h 59m 03.2s 44 32' 16" IC 5070 Bright Nebula 60.0'x50.0' 8 20h 51m 01.1s 44 12' 13" NGC 6960 Supernova Remnant 70.0'x6.0' 7 20h 45m 57.0s 30 44' 12" NGC 6979 Bright Nebula 7.0'x3.0' 20h 51m 14.9s 32 10' 14" NGC 6992 Bright Nebula 60.0'x8.0' 7 20h 56m 39.0s 31 44' 16" M 29 Open Cluster 10.0' 6.6 20h 24m 11.6s 38 30' 58" M 39 Open Cluster 31.0' 4.6 21h 32m 10.4s 48 26' 40" NGC 6826 Planetary Nebula 36" 8.8 19h 44m 58.8s 50 32' 21" NGC 7026 Planetary Nebula 45" 10.9 21h 06m 31.4s 47 52' 28" NGC 6888 Bright Nebula 18.0'x13.0' 10 20h 12m 20.0s 38 22' 18" NGC 6946 Galaxy 11.5'x9.8' 9 20h 35m 01.0s 60 10' 19" Challenge Objects Object Type Size Mag RA Dec PK 64+ 5.1 Planetary Nebula 5" 9.6 19h 35m 02.3s 30 31' 45" Sh2-112 9.0'x7.0' Cygnus ygnus is a spectacular summer constellation. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

TIMOTHY BARKER^ ~2 Unclas

The Ionization Structure of Planetary Nebulae VIII. NGC 6826 TIMOTHY BARKER^ ~2 Department of Physics and Astronomy Wheaton College Received (hASA-CR-180142) THE ICNJZA'IICti STRUCTUHE b87- 175 81 OF PLANETARY IEEULAE. E: LJGC tE26 (Wheatcn CCfl.) 34 p CSCL 03A Unclas G3/84 43731 'Visiting Astronomer, Kitt Peak National Observatory, National Optical Astronomy Observatories, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under contract with the National Science Foundation. 2Guest observer with the International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite, NASA grant NSG 5376. - L$~DL..J,-~~/~'-~ , I , Page 2 ABSTRACT Spectrophotometric observations of emission-line intensities over the spectral range 1400-7200 A have been made in seven positions in the planetary nebula NGC 6826. The O++ electron temperature varies little from 8900 K throughout the nebula; the Balmer continuum electron temperature averages 1500 K higher. The h4267 C I1 line intensities imply C++ abundances that are systematically higher than those determined from the h1906, 1909 C I111 lines, but because of uncertainties in the intensities of the UV lines relative to the optical ones, this discrepancy is less conclusively demonstrated in NGC 6826 thad in other planetaries in this series. Standard equations used to correct for the existence of elements in other than the optically observable ionization stages give results that are consistent and also in approximate agreement with abundances calculated using ultraviolet lines in the few cases where the relevant ultraviolet lines are measurable. The logarithmic abundances (relative to H=12.00) are: Hem10.97, 008.60, N07.71, Nez7.96, C08.53, Ars6.11, and S=6.77.