The Relationship Between Copyright Law and Development in the Jamaican Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leroy Sibbles Love Won't Come Easy / Keep on Knocking Mp3, Flac, Wma

Leroy Sibbles Love Won't Come Easy / Keep On Knocking mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Love Won't Come Easy / Keep On Knocking Country: UK Released: 1987 Style: Roots Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1204 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1395 mb WMA version RAR size: 1529 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 540 Other Formats: MP3 DTS AC3 ASF AA VOX WAV Tracklist A –Leroy Sibbles Love Won't Come Easy B –Jacob Miller Keep On Knocking Notes Comes in a Greensleeves Disco sleeve Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Leroy Heptones* / Leroy Jachob Miller* - Love Rockers none Heptones* / none Jamaica 1979 Won't Come Easy / Keep International Jachob Miller* On Knocking (12") The Heptones / Pablo All The Heptones / Stars / Jacob Miller / Pablo All Stars / Rockers All Stars - Love Greensleeves GRED 22 Jacob Miller / Won't Come Easy / GRED 22 UK 1979 Records Rockers All Rockers Dub / Keep On Stars Knocking / Original Rockers (12") Leroy Heptones* / Leroy Jachob Miller* - Love dsr8223 Heptones* / Message dsr8223 Jamaica 1988 Won't Come Easy / Keep Jachob Miller* On Knocking (12") Love Won't Come Easy / Rockers none Jacob Miller none Jamaica Unknown Keep On Knocking (12") International Related Music albums to Love Won't Come Easy / Keep On Knocking by Leroy Sibbles 1. Augustus Pablo - Rockers International 2. Jacob Miller, Joe Gibbs & The Professionals - Back Yard Movement 3. Jacob Miller - Tenement Yard 4. The Heptones - Sweet Talking / Sweet Dubbing 5. Stranger Cole / Leroy Sibbles / Bullwackies All Stars - The Time is Now / Revolution / Take Time 6. Jacob Miller / The Heptones - Tenement Yard / Book Of Rules 7. -

Mothers in Science

The aim of this book is to illustrate, graphically, that it is perfectly possible to combine a successful and fulfilling career in research science with motherhood, and that there are no rules about how to do this. On each page you will find a timeline showing on one side, the career path of a research group leader in academic science, and on the other side, important events in her family life. Each contributor has also provided a brief text about their research and about how they have combined their career and family commitments. This project was funded by a Rosalind Franklin Award from the Royal Society 1 Foreword It is well known that women are under-represented in careers in These rules are part of a much wider mythology among scientists of science. In academia, considerable attention has been focused on the both genders at the PhD and post-doctoral stages in their careers. paucity of women at lecturer level, and the even more lamentable The myths bubble up from the combination of two aspects of the state of affairs at more senior levels. The academic career path has academic science environment. First, a quick look at the numbers a long apprenticeship. Typically there is an undergraduate degree, immediately shows that there are far fewer lectureship positions followed by a PhD, then some post-doctoral research contracts and than qualified candidates to fill them. Second, the mentors of early research fellowships, and then finally a more stable lectureship or career researchers are academic scientists who have successfully permanent research leader position, with promotion on up the made the transition to lectureships and beyond. -

Bass Culture

Bass Culture Traduit de l’anglais par , e Bass Culture When reggae was king Photographie de couverture : King Tubby. Photographie de quatrième de couverture : Mikey Dread. © .. pour les illustrations. © Lloyd Bradley, . © Éditions Allia, Paris, , , pour la traduction française. Pour Diana, Georges et Elissa. “Les gens pour lesquels le reggae a été inventé ne l ’ont jamais décomposé en styles distincts. Non. C ’est une musique qui vient de l ’esclavage, en passant par le colo nialisme, donc c ’est bien plus qu ’un simple style. Venant par la route de la patate ou la route des bananes ou les flancs des collines, les gens chantent. Pour se débar - rasser de leurs frustrations et élever leur esprit, les gens chan tent. C’était aussi une forme de distraction pendant les week-ends, que ce soit à l ’église ou à une “neuf nuits ” , ou simplement devant . Une veillée caribéenne se pro longe ta maison, tu allais te mettre à chanter. Tu chantes en taillant ta traditionnellement pen dant neuf nuits. (Toutes les notes sont du traducteur.) haie, tu chantes en bêchant ton jardin. La musique est une vibra- tion. C ’est un mode de vie. Il faut bien comprendre que ce n ’est pas seulement cette musique que l ’on joue : c ’est un peuple … une culture … une attitude, un mode de vie qui émane d ’un peuple. ” Bass Culture : quand le reggae était roi a été une véritable aventure. Elle m’a emmené en Jamaïque, à New York, à Miami, dans certains quartiers de Londres dont j’avais oublié l’existence, et dans les recoins les plus profonds de ma collection de disques. -

Sly & Robbie – Primary Wave Music

SLY & ROBBIE facebook.com/slyandrobbieofficial Imageyoutube.com/channel/UC81I2_8IDUqgCfvizIVLsUA not found or type unknown en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sly_and_Robbie open.spotify.com/artist/6jJG408jz8VayohX86nuTt Sly Dunbar (Lowell Charles Dunbar, 10 May 1952, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (b. 27 September 1953, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; bass) have probably played on more reggae records than the rest of Jamaica’s many session musicians put together. The pair began working together as a team in 1975 and they quickly became Jamaica’s leading, and most distinctive, rhythm section. They have played on numerous releases, including recordings by U- Roy, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Culture and Black Uhuru, while Dunbar also made several solo albums, all of which featured Shakespeare. They have constantly sought to push back the boundaries surrounding the music with their consistently inventive work. Dunbar, nicknamed ‘Sly’ in honour of his fondness for Sly And The Family Stone, was an established figure in Skin Flesh And Bones when he met Shakespeare. Dunbar drummed his first session for Lee Perry as one of the Upsetters; the resulting ‘Night Doctor’ was a big hit both in Jamaica and the UK. He next moved to Skin Flesh And Bones, whose variations on the reggae-meets-disco/soul sound brought them a great deal of session work and a residency at Kingston’s Tit For Tat club. Sly was still searching for more, however, and he moved on to another session group in the mid-70s, the Revolutionaries. This move changed the course of reggae music through the group’s work at Joseph ‘Joe Joe’ Hookim’s Channel One Studio and their pioneering rockers sound. -

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, in 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 Cell * [email protected]

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, IN 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 cell * [email protected] BOOKS Women in Jamaican Music McFarland, Spring 2020 Operation Jump Up: Jamaica’s Campaign for a National Sound, Half Pint Press, 2018 Alpha Boys School: Cradle of Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2017 Songbirds: Pioneering Women in Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2014 Don Drummond: The Genius and Tragedy of the World’s Greatest Trombonist, McFarland, 2013 Ska: The Rhythm of Liberation, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013 Ska: An Oral History, McFarland, 2010 Reggae from Yaad: Traditional and Emerging Themes in Jamaican Popular Music, ed. Donna P. Hope, “Freedom Sound: Music of Jamaica’s Independence,” Ian Randle Publishers, 2015 Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, Melville House, 2011 PUBLICATIONS “Rhumba Queens: Sirens of Jamaican Music,” Jamaica Journal, vol. 37. No. 3, Winter, 2019 “Getting Ahead of the Beat,” Downbeat, February 2019 “Derrick Morgan celebrates 60th anniversary as the conqueror of ska,” Wax Poetics, July 2017 Exhibition catalogue for “Jamaica Jamaica!” Philharmonie de Paris Music Museum, April 2017 “The Sons of Empire,” Deambulation Picturale Autour Du Lien, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art 2015 “Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Super Ape,” Wax Poetics, November, 2015 “Don Drummond,” Heart and Soul Paintings, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art, 2012 “Spinning Wheels: The Circular Evolution of Jive, Toasting, and Rap,” Caribbean Quarterly, Spring 2015 “Lonesome No More! Kurt Vonnegut’s -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

Sean Paul and His New Music 24 the KING of BLING the Joe Rodeo Is the King of Bling

Summer 2012 Sharp & DJOE ReODtEaO MiAlSeTEdR COLLECTION NEW EDITION Fashion Quick Look A Visionary Summer to Fall Transition Motorcycle Maker “Copper Mike” creates a functioning work of art How is Dr. Shaquille O’Neal doing? Put it on and light up the surrounding. Broadway Collection Mens Diamond Watch 5ctw Diamond Weight Fine Swiss Quartz Movement Stainless-Steel Case Deployment-Buckle Clasp Black Rubber Band Summer 2012 CONTENTS Joe Rodeo magazine tries to create a culture FOR MORE INFO VISIT OUR WEBSITE is hot www.joerodeo.com inWhat this issue JOE RODEO Joe Rodeo, sophistication Copper Mike Sharp & Detailed “Copper Mike” builds and passion The eye catching jewelry and 5 motorcycles from scratch 10 The story of success Put your ear to watches has been custom by finding old antiques the new designed for Hip-Hop artists. With and then through hand The Art of Copper and Speed Keep your windows open on this Joe Rodeo released several carving, hammering Mike Cole the Long Island chopper those steamy days coming lines of exclusive and magnificent 10 copper, and blowing who makes beauty up here in Long Island. Don’t collection of Diamond Watches. glass into them, he be surprised to hear Slippaz, The Style ranges from Classic creates a functioning Felion, Fenom or Nitty one and sophisticated all the way to Dr. Shaquille O’Neal work of art. day in the car next to you. One year later after retirement 7 hip and modern. Each design is 36 unique and hand crafted to your taste. Urban Safari Summer/Fall 2012 quick look 9 Sean Paul and his new music 24 THE KING OF BLING The Joe Rodeo is the king of bling. -

Eighty-Three Years of Gypsy Days at NSU Activities Fair Provides Fun and Information for NSU Students

THE OF NORTHERN STATE UNIVERSITY September 2 2 , I 9 9 9 Volume 9 8 , Issue 2 • [email protected] Political correctness Hoines & D e erform How to contact the Student Publications staff: Opinion columnist Cody Tesnow Megan Hoines and Kay Daigle News Room. 605-626-2534 examines the foes of being packed the Red Rooster with Ad. Staff & Answering Machine 605-626-2559 politically correct in our society over 100 people in attendance P.O. Box 861 • 1200 S. Jay St. • Aberdeen, SD 57401 See page 4. for their first debut. See page 9. [email protected] • [email protected] Eighty-three years of Gypsy Days at NSU Jason Lem e Campus Reporter or the eighty-third year, Gyps will also be crowned during the Northern State University ceremony. Coronation is free and Fwill celebrate Gypsy Days open to the public. Sept. 20-25. In preparation for the Campus tours will be given Friday, next millennium, this year's theme is Sept. 24, by Student Ambassadors "Going Out With a Bang!" from 10 a.m. to noon and from 2 to 4 In the early part of the century, p.m. beginning at the Beckman students on the NSU campus formed Building, at 620 15th Ave. S.E. friendships with a group of people of An all-class reunion picnic will be Romani descent. They would travel held from lla.m. to 2 p.m. Friday in through the area every year at the the Beckman Building parking lot. time of NSU's homecoming Cost is $5 per person. -

Rototom Reggae University 2008

ROTOTOM REGGAE UNIVERSITY 2008 ! ! July 4 FROM RUDE BOYS TO SHOTTAS Violence and Alienation in Jamaican Cultural Expression Lecture, film-shoots and selected music by !Marlene Calvin JA/DE July 5 RASTAFARI - Unity and Diversity of a Global Philosophy with prof Werner Zips from the University of Wien, Bob Andy, Sydney Salmon, Jamaican artist who lives in Shashamane, and Leila Worku, director of the Ethiopia’s Bright Millennium Campaign. Film shoots from “Rastafari: Death to Black and White !Downpressors” by Werner Zip July 6 REGGAE IN ITALY with Bunna of Africa Unite, Treble, former SudSoundSystem and nowadays producer, Jaka, entertainer, singer and radio dee-jay, Paolo Baldini, members of Train To Roots, Suoni Mudù, Villa Ada Posse, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Anzikitanza, the singers of Big Island Records, Filippo Giunta (Rototom), Steve Giant (Rasta Snob), Vito War (Reggae Radio Station on Popolare Network), Macromarco (Gramigna Sound), Lampadread (OneLoveHi Powa). July 10 ROOTS MUSIC IN THE DANCEHALL !with Michael Rose and Alborosie ! ! July 10 DEEP ROOTS MUSIC A meeting with Howard Johnson, film-maker !and director of “DeepRootsMusic” ! July 7 FEMALE REGGAE A Change of Position from Margin to Centre? with Jamaican artist Ce’Cile, Yaz Alexander, from UK, The Reggae Girls from Italy, and The Serengeti from Sweden. !Dub-poetry performance by Jazzmine TuTum ! July 7 NEW TRENDS IN THE DANCEHALL with Wayne Marshall, Bugle, Teflon, !and Daseca producers ! July 8 EVERLASTING FOUNDATION The Crucial Role of Musicians In Jamaica with Dean Frazer, -

Ming Bridges (Pg 22) Is Eager to Show What She’S Got in Morphosis

FEB - JUL 2014 ISSUE 38 FRIES FRENZY MING vintage dress-up '60S band reunion BRIDGES COSPLAY fever 2 HYPE where to find HYPE COMPLIMENTARY COPIES OF HYPE ARE AVAILABLE AT THE FOLLOWING PLACES: Actually Peek! orchardgateway #03-18 36 Armenian Street #01-04/02-04 Beer market 3B River Valley Road Rockstar by Soon Lee #01-17/02-02 Cineleisure Orchard #03-08 Berrylite SabrinaGoh 80 Parkway Parade Road #B1-83J Orchard Central #02-11/12 201 Victoria Street #05-03 1 Seletar Road #01-08 School of the Arts 1 Zubir Said Drive COld Rock 2 Bayfront Avenue #B1-60 St Games Cafe The Cathay #04-18 Cupcakes with love Bugis+ #03-16/17 10 Tampines Central 1 Tampines 1 #03-22 TAB 442 Orchard Road Dulcetfig #02-29 Orchard Hotel 41 Haji Lane Threadbare & Squirrel Eighteen Chefs 660 North Bridge Road Cineleisure Orchard #04-02 The Cathay #B1-19/20 Timbre@The Arts House Tiong Bahru Plaza #02-K1/K6 1 Old Parliament Lane #01-04 Five & Dime Timbre@The Substation 297 River Valley Road 45 Armenian Street Hansel The Muffinry Mandarin Gallery #02-14 112 Telok Ayer Street Ice Cream Chefs The Garden Slug Ocean Park Building #01-06 55 Lorong L Telok Kurau 12 Jalan Kuras (Upper Thomson) #01-59/61 Bright Centre Island Creamery Victoria Jomo 11 King Albert Park #01-02 9, 49 Haji Lane Serene Centre #01-03 Holland Village Shopping Mall #01-02 Vol.Ta The Cathay #02-09 J Shoes Orchard Cineleisure #03-03 Wala Wala 31 Lorong Mambong Leftfoot Far East Plaza #04-108 Orchard Cineleisure #02-07A The Cathay #01-19/20 NEW E IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER 22 MING MORPHS The girl next door returns with a new album but.. -

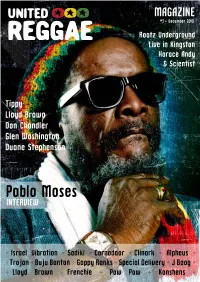

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Central American Immigrant Women's Perceptions of Adult Learning: a Qualitative Inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chupina, Ana Guisela, "Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 933. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/933 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: A qualitative inquiry by Ana Guisela Chupina A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Education (Adult Education) Program of Study Committee: Nancy J. Evans, Major Professor Jackie M. Blount Deborah W. Kilgore Carlie C. Tartakov Michael B. Whiteford Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Ana Guisela Chupina, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3145633 Copyright 2004 by Chupina, Ana Guisela All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.