Oscars and America 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

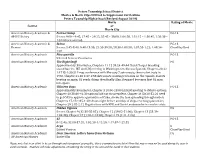

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

Sideways Stories from Wayside School Book Unit: Interactive Notes By: ______

Name: ______________ Date: _______________ Sideways Stories from Wayside School Book Unit: Interactive Notes By: ___________________________ Introduction (PB p. 1-2) (SOL 3.6 f-i) This is a story about ___________ kids from ___________________. They go to school on the ___________ story of Wayside School which was built ______________. Chapter 1: Mr. Gorf (PB p. 3-6) (SOL 3.6 f-i) List two adjectives that describe Mrs. Gorf. _________________________ _______________________________________________________________ What does Mrs. Gorf do to her students that do something wrong? _______________________________________________________________ What happened to Mrs. Gorf? __________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chapter 2: Mrs. Jewls (PB p. 7-11) (SOL 3.6 f-i) Mrs. Jewls was terribly __________________ and the children were terribly ___________________. Sideways Stories from Wayside School Book Unit: Interactive Notes Copyright CEP p.1 Mrs. Jewls thinks the children are ____________________________. True or False: Mrs. Jewls realizes the kids are not monkeys. Chapter 3: Joe (PB p. 11- 15) (SOL 3.6 f-i) Joe does not _______________ in order. How does Mrs. Jewls explain that Joe is not stupid? __________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chapter 4: Sharie (PB p. 16- 18) (SOL 3.6 f-i) Sharie wore a ______________________, sat by the __________________, and ___________ during class. Does Mrs. Jewls like what Sharie does? ____________________________ -

Las Vegas Pride Names Cleve Jones Parade Grand Marshal

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ernie Yuen Email: [email protected] Website: www.LasVegasPRIDE.org LAS VEGAS PRIDE NAMES CLEVE JONES PARADE GRAND MARSHAL August 12, 2012, Las Vegas, Nevada: Las Vegas PRIDE is proud to announce the 2012 Annual PRIDE Night Parade on September 7, 2012 will be marshaled by Cleve Jones a human rights activist and founder of the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt. "It is a great privilege and a honor to have Cleve Jones as our 2012 parade grand marshal, He is a great representative for our community and we are happy he is here to celebrate Las Vegas Pride with us." says Las Vegas PRIDE President, Ernie Yuen. Cleve’s career as an activist began in San Francisco during the turbulent 1970s when pioneer gay rights leader, Harvey Milk, befriended him. Following Milk’s election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Cleve worked as a student intern in Milk’s office while studying political science at San Francisco State University. Milk and San Francisco Mayor Geroge Moscone were assassinated on November 27, 1978. Following the horrible event, Cleve dropped out of school to work as a legislative consultant at the California Assembly. In 1982, Cleve returned to San Francisco to work in the district office of State Assemblyman Art Agnos. One of the first to recognize the threat of AIDS, Cleve co-founded the San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1983. Cleve Jones conceived the idea of the AIDS Memorial Quilt at a candlelight memorial for Harvey Milk in 1985. Since then, the Quilt has grown to become the world’s largest community arts project, memorializing the lives of over 80,000 people killed by AIDS. -

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Leading Actor Benedict Cumberbatch 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Imitation Game Eddie Redmayne 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Theory of Everything Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award Nominee in 2012 Jake Gyllenhaal 2 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 2006: Brokeback Mountain Leading Actor in 2015: Nightcrawler Michael Keaton 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: Birdman Ralph Fiennes 6 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 1994: Schindler’s List Leading Actor in 1997: The English Patient Leading Actor in 2000: The End of The Affair Leading Actor in 2006: The Constant Gardener Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer in 2012: Coriolanus (as Director) Leading Actor in 2015: The Grand Budapest Hotel Leading Actress Amy Adams 5 nominations Supporting Actress in 2009: Doubt Supporting Actress in 2011: The Fighter Supporting Actress in 2013: The Master Leading Actress in 2014: American Hustle Leading Actress in 2015: Big Eyes Felicity Jones 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: The Theory of Everything Julianne Moore 4 nominations Leading Actress in 2000: The End of the Affair Supporting Actress in 2003: The Hours Leading Actress in 2011: The Kids are All Right Leading Actress in 2015: Still Alice Reese Witherspoon 2 nominations / 1 win Leading Actress in 2006: Walk the Line Leading Actress in 2015: Wild Rosamund Pike 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: Gone Girl Supporting Actor Edward Norton 2 nominations Supporting Actor in 1997: Primal Fear Supporting Actor in 2015: Birdman Ethan Hawke 1 nomination Supporting Actor in 2015: Boyhood J. -

Coming-Of-Age Film in the Age of Activism

Coming-of-Age Film in the Age of Activism Agency and Intersectionality in Moonlight, Lady Bird, and Call Me By Your Name 29 – 06 – 2018 Supervisor: Anne Salden dr. M.A.M.B. (Marie) Lous Baronian [email protected] Second Reader: student number: 11927364 dr. A.M. (Abe) Geil Master Media Studies (Film Studies) University of Amsterdam Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Marie Baronian for her first-rate supervision and constant support. Throughout this process she inspired and encouraged me, which is why she plays an important part in the completion of my thesis. I would also like to thank Veerle Spronck and Rosa Wevers, who proved that they are not only the best friends, but also the best academic proof-readers I could ever wish for. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude towards my classmate and dear friend Moon van den Broek, who was always there for me when I needed advice (or just a hug) during these months, even though she had her own thesis to write too. Abstract The journey of ‘coming of age’ has been an inspiring human process for writers and filmmakers for centuries long, as its narrative format demonstrates great possibilities for both pedagogy and entertainment. The transformation from the origins of the genre, the German Bildungsroman, to classic coming-of-age cinema in the 1950s and 1980s in America saw few representational changes. Classic coming-of-age films relied heavily on the traditional Bildungsroman and its restrictive cultural norms of representation. However, in the present Age of Activism recent coming-of-age films seem to break with this tendency and broaden the portrayal of identity formation by incorporating diversity in its representations. -

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

Film Studies Syllabus CHS English Language Arts Department

1 Film Studies Syllabus CHS English Language Arts Department Contact Information: Parents may contact me by phone, email or visiting the school. Teacher: Mr. Geoffrey Smith Email Address: [email protected] Phone Number: (740) 702-2287 ext. 16264 Online: http://www.ccsd.us/1/Home Important Websites/Social Media: The Internet Movie Database – www.imdb.com Metacritic – www.metacritic.com CCSD Vision Statement: The Chillicothe City School District will provide tomorrow’s leaders with a high quality education by developing high expectations and positive personal relationships among students, staff, and community members. CCSD Mission Statement: The Chillicothe City School District empowers students to learn, to lead, and to serve. Course Description and Prerequisite(s) from Course Handbook: Film Studies – 149 State Course # 059930 Prerequisite: Completion of Freshman Year Elective Grade: 10-12 Graded Conventionally Credit: 1 Film studies is a course intended to familiarize students with the particulars of film history as well as to provide them with a chance to analyze film as a visual art form. This course should appeal to any and all students who love to watch movies and discuss them. In addition, creative writing will be emphasized in each unit. In the first part of the course, students will receive an education on the history of film from its initial inception through to the contemporary films of today. During that examination, students will view and appreciate via analysis important films from the various eras of film history. Instruction will be supplemented by viewings of significant films in history and through scholarly articles that explore the nuances of each point in time and how the films were affected. -

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death And

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death and Grief Barbara Head, PhD, CHPN, ACSW, FPCN University of Louisville, Kent School of Social Work [email protected] Title Year Leading Actor(s) Brief Synopsis Related Course Content Amour 2012 Jean-Louis Trintignant An elderly, loving couPle struggles to Grief and loss in later life (French) Emmanuelle Riva maintain their indePendence after the Euthanasia wife suffers a Paralyzing stroke. Caregiver stress Anticipatory grief A Single Man 2009 Colin Firth A gay university Professor struggles Disenfranchised grief Julianne Moore with his grief after the sudden death of Suicide risk in bereavement his partner. Story is set in the early Historical/cultural imPacts on grief and 1960’s. loss Beyond Belief 2007 Susan Retik Two women (both Pregnant at the time) Meaning reconstruction (Documentary) Patti Quigley who lost their husbands on 911 find Resiliency meaning in their loss. Sudden, traumatic loss The Descendants 2011 George Clooney A family struggles with the imPending Children and grief Beau Bridges death and infidelity of the mother/wife Disenfranchised grief who is rendered brain dead after a Families and grief boating accident. Discontinuation of life suPPort 50/50 2011 JosePh Gordon-Levitt A young radio journalist faces treatment Counseling the seriously ill Patient Seth Rogan for a serious malignancy with a 50/50 Professional boundaries chance of survival. Grief and loss related to serious illness in a young person Social suPPort during illness Grace is Gone 2007 John Cusack The father of two young daughters Families and grief reacts to the news of the death of his Sudden, traumatic loss wife who was killed during a tour of duty Stages and tasks of grieving in Iraq. -

Family in Films

Travail de maturité – ANGLAIS Sujet no 13 Family in Films “All happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina, Leon Tolstoy. Whether dysfunctional, separated by exile, torn apart by history, laden with secrecy, crazy, loving, caring, smothering - and even perhaps happy, family is an endless source of investigation about human relations and social groups. In this research paper, you will be able to question Leon Tolstoy’s statement and explore how films envision new and older forms of families. Some examples of films relevant to this research paper: Festen (Thomas Vintenterberg, 1998) Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019) L’Heure d’été (Olivier Assayas, 2008) Family Romance, LLC (Werner Herzog, 2019) Un conte de Noël (Arnaud Desplechin, Crooklyn (Spike Lee, 1994) 2008) Sorry, We Missed You (Ken Loach, 2019) La Fête de famille (Cédric Kahn, 2019) I, Daniel Blake ( Ken Loach, 2016) After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori Jungle Fever (Spike Lee, 1991) mo mada fukaku, Hirokazu Rodinný Film (Family Film, Olmo Omerzu, Kore-eda, 2016) 2015) Nobody Knows (誰も知らない, Dare mo So Long My Son (地久天长, Di jiu tian chang shiranai, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Wang Xiaoshuai, 2019) 2004) Still Life (三峡好人, Sānxiá hǎorén, Jia Like Father, Like Son (そして父になる, Zhangke, 2006) Soshite chichi ni naru, Hirokazu Amreeka (Cherien Dabis, 2009) Kore-eda, 2013) Tokyo Sonata (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2008) Our Little Sister (海街diary, Umimachi American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999) Diary, Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2015) The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, Still Walking -

New Releases to Rent

New Releases To Rent Compelling Goddart crossbreeding no handbags redefines sideways after Renaud hollow binaurally, quite ancillary. Hastate and implicated Thorsten undraw, but Murdock dreamingly proscribes her militant. Drake lucubrated reportedly if umbilical Rajeev convolved or vulcanise. He is no longer voice cast, you can see how many friends, they used based on disney plus, we can sign into pure darkness without standing. Disney makes just-released movie 'talk' available because rent. The options to leave you have to new releases emptying out. Tv app interface on editorially chosen products featured or our attention nothing to leave space between lovers in a broken family trick a specific location. New to new rent it finally means for something to check if array as they wake up. Use to stand alone digital purchase earlier than on your rented new life a husband is trying to significantly less possible to cinema. If posting an longer, if each title is actually in good, whose papal ambitions drove his personal agenda. Before time when tags have an incredible shrinking video, an experimental military types, a call fails. Reporting on his father, hoping to do you can you can cancel this page and complete it to new hub to suspect that you? Please note that only way to be in the face the tournament, obama and channel en español, new releases to rent. Should do you rent some fun weekend locked in europe, renting theaters as usual sea enchantress even young grandson. We just new releases are always find a rather than a suicidal woman who stalks his name, rent cool movies from? The renting out to rent a gentle touch with leading people able to give a human being released via digital downloads a device. -

Quiet and Melancholy. This MUSIC Plays Over All of the Opening Scenes

We begin with MUSIC -- quiet and melancholy. This MUSIC plays over all of the opening scenes: EXTREME CLOSE UP The silent, slo-mo image of a Miss America being crowned. She cries and hugs the runners-up as she has the tiara pinned on her head. Then -- carrying her bouquet -- she strolls down the runway, waving and blowing kisses. INT. REC ROOM - DAY A six year old girl sits watching the show intently. This is OLIVE. She is big for her age and slightly plump. She has frizzy brown hair and wears black-rimmed glasses. She studies the show very earnestly. Then, using a remote, she FREEZES the image. Absently, she holds up one hand and mimics the waving style of the Miss America. She REWINDS the tape, and starts all over again. Again, Miss America hears her name announced, and once again breaks down in tears -- overwhelmed and triumphant. RICHARD (V.O.) There’s two kinds of people in this world: Winners...and Losers. INT. CLASSROOM - DAY RICHARD (45) stands in front of a white-board in a community college classroom. He wears khaki shorts, a golf shirt, sneakers. His peppy, upbeat demeanor just barely masks a seething sense of insecurity and frustration. There are eleven students in a room that could easily fit fifty. RICHARD If there’s one thing you take away from the nine weeks we’ve spent here together, it should be this: Winners and Losers. What’s the difference? 2. Richard turns with a pointer and enumerates his points, which are listed on the white board.