Hand Drum Banjo Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Battle Station Model by Russell Barnes

Building a Battle Station Model By Russell Barnes I. Introduction The summer is usually a pretty difficult time for me to work in my workshop. Chores abound around the house and there is seemingly some-thing to do almost every day that precludes any useful time spent in the workshop. The summer of 2004 was no different. By the time late July rolled around, I was desperate. I had not made anything for over a month. Something had to be done. What to do? Then it hit me. I was looking over the latest Model Expo catalogue and saw they still offered kit models of small battle stations. Not wanting to build a kit, I saw the potential for a quick scratch built project. Over the next two weeks I built a battle station model that turned out to be quite a conversation piece. As fate would have it, that model was destroyed when Hurricane Katrina washed away the local museum. I have decided to replace the battle station model, but it occurred to me that others might benefit from my experience having built it. So, I redrew the plans, making some improve-ments, and decided to set down a guide to building the model. I am not an expert and I make no claim that my methods are the only way to build the model. Someone building from these plans should view my words as a collection of helpful hints rather than a map to follow in order to arrive at a desired result. I envision this project as an introduction to scratch building. -

Stainless and Mild Steel Drilling FOOD & BEVERAGE

FOOD & BEVERAGE Stainless and Mild Steel Drilling CRYOBIT® DRILL BITS APPLICATION STORY • Maintenance groups in most food and beverage plants face the same challenge: drilling stainless. While stainless is not a hard metal, it will harden quickly if it is not drilled properly. • Some use cobalt bits to drill stainless, but these bits have a thick web and will not pass bulky chips (like aluminum and mild steel). Standard HSS bits typically dull quickly drilling stainless. A major non-dairy creamer production facility directed their maintenance group to test Cryobit drill bits against “premium” HS and cobalt drill bit samples from four companies. FEATURES AND BENEFITS • After extensive testing, they concluded Cryobit drill bits possess • Designed to be tough enough for abusive hand the toughness and diversity they require. Cryobit drill bits drilled up to 6 times more holes in stainless steel. Additionally, drilling yet open enough to pass large softer chips they found Cryobit drill bits to be perfect for drilling softer without binding metals like carbon steel and aluminum. • 50% Flute resists breaking caused by excessive flexing TIPS FOR DRILLING STAINLESS STEEL Drilling stainless requires 50% more feed pressure than • CM-8™ alloy steel combines with the patented mild steel and a reduced RPM. Cryophase™ treatment to help keep the drill bit sharp in the toughest applications Stainless steel work-hardens up to 45 Rockwell-C in some cases • 3-Flats on the drill bit shank makes these bits perfect • Too little feed pressure work- for keyless chucks commonly found in hand drills hardens the immediate drilling surface Cryobits can be used by hand • Available in 29 piece jobber lengths to 1/2'' and in • A dull bit will work-harden or in drill presses… the immediate drilling surface reduced shank bit sizes up to 1-5/16'' • A center punch work-hardens the starting divot • Pilot holes are NOT beneficial when drilling stainless because they can work-harden the hole Always use cutting fluid for drilling stainless to promote cleaner hole finish and double …or lathes. -

Section W - Machinery

Section W - Machinery SECTION W - TABLE OF CONTENTS A Section W Contents: B Würth Portable Machinery...................... 2 - 3 WORK SMARTER, C Kreg Machinery............................................. 4 Page W-4 SawStop Saws....................................... 5 - 13 NOT HARDER D SCM Sliding Table Saws.....................14 - 15 SCM Edgebanders..............................16 - 20 With High Technology EE SCM CNC Routers.............................. 21 - 22 FF SCM Combination Machine...................... 23 Machinery That Delivers SCM Line Boring Machine......................... 24 G SCM Bandsaw.............................................25 Top Quality Results Pages W-5 - W-13 SCM Shaper................................................ 26 H SCM Wide Belt Sander.......................27 - 28 SCM Jointer................................................. 29 I SCM Planer..................................................30 Pages W-14 - W-31 SCM Jointer/Planer..................................... 31 J Gannomat Dowel Insertion Machine.........32 KK Gannomat Case Clamps............................ 33 Gannomat Drilling/ L Inserting Machine................................34 - 37 Pages W-32 - W-40 Gannomat Machine Accessories........38 - 40 MM NN Looking to sell or buy used equipment? OO Scan the QR code or visit www.wurthbaersupply.com and click on PP Post Classified Ad Free. QQ The service is free to use and all transactions are processed between R buyer and seller. S T U V WW XX Y Note: Some of the items in this section are not available -

BRAD POINT DOWEL DRILL Solid Carbide • 57.5Mm & 70Mm Long • 10Mm X 30Mm Shank* Special Solid Carbide Grade Cutting Flute for Long Lasting Performance

BRAD POINT BORING Carbide Tipped • 57mm Long • 10mm x 30mm Shank* Tool No. Tool No. ØD B Ød L LH RH 3mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301003 201003 † 3.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301032 201032 4mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301004 201004 4.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm — 201045 Brad Point Boring Bits are coated with a non-stick 5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301005 201005 coating for longer lasting cutting edge and tool life. This special Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) non-stick color coating is 5.1mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301051 201051 applied onto the bit at a temperature of 570° F. The coating reduces the 5.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301052 201052 friction between the chip and the body inside the flute and it helps to clear 5.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301055 201055 the chips out of the hole during the drilling, creating a cooler drilling area 6mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301006 201006 with no burning and a longer lasting cutting edge. 6.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301065 201065 6.7mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301067 201067 In cases where the carbide tip cutting edges are coated, there is no need to sand the coating off before use. Once the tool starts drilling, the coating 7mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301070 201070 is quickly cleared off the needed cutting edge. 7.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301075 201075 8mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301008 201008 d d 8.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301082 201082 9mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301090 201090 10mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301010 201010 10.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301105 201105 12mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301012 201012 14mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301014 201014 L L 15mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301015 201015 16mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301016 — B B 17mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301017 201017 18mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301018 201018 19mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301019 201019 D D 20mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301020 201020 Left Hand Right Hand 3/16 27mm 10mm 57mm 301047 — 1/4 27mm 10mm 57mm 301007 201007 3/8 27mm 10mm 57mm 301009 201009 1/2 27mm 10mm 57mm 301013 201013 † With solid carbide cutting edge. -

Tools and Machinery of the Granite Industry Donald D

©2013 The Early American Industries Association. May not be reprinted without permission. www.earlyamericanindustries.org The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, Inc. Vol. 59, No. 2 June 2006 The Early American Industries Contents Association President: Tools and Machinery of the Granite Industry Donald D. Rosebrook Executive Director: by Paul Wood -------------------------------------------------------------- 37 Elton W. Hall THE PURPOSE of the Associa- Machines for Making Bricks in America, 1800-1850 tion is to encourage the study by Michael Pulice ----------------------------------------------------------- 53 of and better understanding of early American industries in the home, in the shop, on American Bucksaws the farm, and on the sea; also by Graham Stubbs ---------------------------------------------------------- 59 to discover, identify, classify, preserve and exhibit obsolete tools, implements and mechani- Departments cal devices which were used in early America. Stanley Tools by Walter W. Jacob MEMBERSHIP in the EAIA The Advertising Signs of the Stanley Rule & Level Co.— is open to any person or orga- Script Logo Period (1910-1920) ------------------------------------------- 70 nization sharing its interests and purposes. For membership Book Review: Windsor-Chair Making in America, From Craft Shop to Consumer by information, write to Elton W. Hall, Executive Nancy Goyne Evans Director, 167 Bakerville Road, Reviewed by Elton W. Hall ------------------------------------------------- 75 South Dartmouth, MA 02748 or e-mail: [email protected]. Plane Chatter by J. M. Whelan An Unusual Iron Mounting ------------------------------------------------- 76 The Chronicle Editor: Patty MacLeish Editorial Board Katherine Boardman Covers John Carter Front: A bucksaw, patented in 1859 by James Haynes, and a nineteenth century Jay Gaynor Raymond V. Giordano saw-buck. Photograph by Graham Stubbs, who discusses American bucksaws Rabbit Goody in this issue beginning on page 59. -

The Serpent Website's Squarpent

Squarpent Construction The Serpent Website’s Squarpent © Paul Schmidt 2004 Disclaimer necessitating the later cutting of the ‘Up Tube’ in order to flip the bocal around to the correct direction. This in turn Neither The Serpent Website or the author make any required the addition of reinforcing plywood plates over the guarantees that the following instructions are free of errors, repair, visible in the photo at left. The revised diagrams are or that a resulting instrument (the “Squarpent”), will play at included in this document, and have been verified to be any anticipated level the builder might desire or expect. correct. The website’s downloadable version of the same These instructions are intended to be used as a printable drawing has been replaced with the corrected version as alternative to The Serpent Website’s ‘Squarpent’ well. Be aware to check this area if the original website construction webpage and article, in order to duplicate the instructions have already been viewed or printed. author’s prototype. The resulting instrument is intended to be an educational device, and no promise is made regarding its Materials suitability for performance situations. Refer to www.serpentwebsite.com - 4’ x 8’ sheet of 1/4” plywood (actually 0.2” [0.5 cm] ), with two finished/good sides, preferably exterior grade, preferably hardwood type (Oak, etc.) - scrap of 1/2” [1.3 cm] dia. wooden dowel - scrap of 3/4” [1.9 cm] dia. wooden dowel - wood glue, exterior (water resistant) type, preferably gel formulation to resist running, e.g. Elmer’s “Pro Bond Weather Resistant Wood Glue for Exterior Use” - 5 minute epoxy (2-part) - mouthpiece; serpent mouthpiece preferable (see Makers page of Serpent Website), but trombone/baritone/ euphonium type will work - steel wire, for twisting twight to hold objects together during gluing (approx. -

Download PDF Tools Catalog Now!

2011. PPRREECCIISSIIOONN SSOOLLIIDD CCAARRBBIIDDEE MMIICCRROOTTOOOOLLSS TABLE OF CONTENTS PCB SRD Jewelry Signage End‐Mills 3-15 DeepReach 2‐flute, fish tail ________________________________ 3 DeepReach 2‐flute, ball nose_______________________________ 3 DeepReach 3‐flute, fish tail ________________________________ 4 DeepReach 3‐flute, ball nose_______________________________ 4 Ultra 3‐flute, fish tail _____________________________________ 5 Pro 2‐flute, fish tail ______________________________________ 6 Pro 2‐flute, ball nose _____________________________________ 7 Pro Metal 2‐flute stub, fish tail _____________________________ 8 Pro Metal 2‐flute stub, ball nose____________________________ 9 ProMetric 2‐flute, fish tail ________________________________ 10 ProMetric 2‐flute, V‐drill point ____________________________ 11 ProMetric 1‐flute, V‐drill point ____________________________ 12 Pro 3‐flute, fish tail _____________________________________ 15 End‐Mills/Down‐Cut (left flute) 13-14 Pro 2‐flute left, fish tail __________________________________ 13 ProMetric 2‐flute left, fish tail _____________________________ 14 Carving Tools 13-13 Pro 4‐flute tapered, ball nose _____________________________ 13 Drill Bits 16-22 Pro Drill Bits 2‐flute 28°, drill point ______________________ 16‐17 ProMetric Drill Bits 2‐flute 35/30° UC, drill point ___________ 18‐19 ProMetric Drill Bits 2‐flute 30° ST, drill point ______________ 19‐21 ProMetric Slot Drill Bits 2‐flute 30° SL, drill point _____________ 22 Router Bits 23-26 Diamond Cut, fish tail ___________________________________ -

Audel™ Mechanical Trades Pocket Manual

Audel™ Mechanical Trades Pocket Manual All New Fourth Edition Thomas Bieber Davis Carl A. Nelson, Sr. Audel™ Mechanical Trades Pocket Manual All New Fourth Edition Thomas Bieber Davis Carl A. Nelson, Sr. Vice President and Executive Publisher: Bob Ipsen Publisher: Joe Wikert Executive Editor: Carol Long Development Editor: Emilie Herman Editorial Manager: Kathryn A. Malm Senior Production Editor: Angela Smith Text Design & Composition: Wiley Composition Services Copyright © 2004 by Wiley Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1986, 1990 by Macmillan Publishing Company, a division of Macmillan, Inc. Copyright © 1983 by The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc. Copyright © 1974 by Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authoriza- tion through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8700. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4447, E-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Introduction to Building: RUDDER ASSEMBLY MANUAL

RUDDER ASSEMBLY MANUAL This useful step-by-step manual has been prepared to help the first-time builder (with no previous building experience) to assemble the rudder tail kit for the Zenith aircraft, from a factory-supplied tail kit. The rudder tail section will require about 12 hours to assemble with just basic skills and tools, and will provide the builder with an excellent introduction to home- building an all-metal Zenith aircraft (in addition to completing the first assembly: the rudder). Building your own aircraft is probably going to be one of the most challenging and rewarding things you will do in your lifetime: imagine, you'll be flying in an aircraft that you have built yourself! Few people get the sensation and freedom of flying. Even fewer also get the reward of flying a plane that they've built themselves! Don't become overwhelmed when building the rudder kit. While it's true that an aircraft is a piece of complex machinery, it is also very straight forward, especially when building from a kit. It's normal that you may initially become overwhelmed and confused, but your initial fears and concerns will disappear as soon as the project starts coming together, and as you get a better understanding of the construction. Zenith aircraft are well-designed light aircraft - engineered specifically as a first-time kit project, using proven materials and simple processes and systems. This RUDDER ASSEMBLY MANUAL has been prepared as a supplement to the complete and detailed Drawings and Manuals for the ZENITH CH 650, STOL CH 701, and CH 750 series aircraft. -

No. 803,911. PATENTED NOW, 7, 1905, J

No. 803,911. PATENTED NOW, 7, 1905, J. G. LEYNER. ROCK CUTTING DRILL BIT, APPLICATION FILED SEP, 2, 1903, S s UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. JOHN GEORGE LEYNER, OF DENVER, COLORADO. ROCKCUTTNG DRILLBT No. 803,911. Specification of Letters Patent. Patented Nov. 7, 1905, Application filed September 2, 1903, Serial No. 171,623, To cult livhon, it nually conce77: more may be used, but I preferably use eight, Beitknown that I, JoHN GEORGELEYNER, a as illustrated. This drill-bit is adapted to be citizen of the United States of America, resid attached to a suitable bar or rod 2 of steel, ing in the city and county of Denver and State which I term the 'drill-bar.’ This drill-bar of Colorado, have invented certain new and use corresponds to the shank portion of the com ful Improvements in Rock-Cutting Drill-Bits: mon form of a rock-drill bit that has its cut and I do declare the following to be a full, ting-point forged on one end of it, while its clear, and exact description of the invention, opposite end is adapted to be struck by a ham Such as will enable others skilled in the art mer. This drill-bar part of my rock-cutting to which it appertains to make and use the drill-bit is adapted to be used in any of the same, reference being had to the accompany rock-cutting engines in use or may be used as ing drawings, and to the figures of reference a hand-drill. The cutting-points are adapt marked thereon, which form a part of this ed to be practically instantaneously attached specification. -

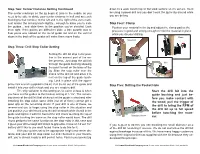

Drill Stop Collar Setting Step Four

Step Two: Center Distance Setting Continued down to a work bench top or flat solid surface so it’s secure. You’ll The center markings on the jig begin at zero in the middle so you be using a power drill and you don’t want the jig to slip around while need to be able to divide your center distance in half and set each you are drilling. bushing to that number, to the left and to the right of the zero mark. Just loosen the locking knob slightly... enough to allow you to slide Step Four: Clamp the guides... and slide them to the position you’ve decided. Lock Position your material in the jig and adjust the clamp pad so the them tight. If the guides are difficult to slide, a little paraffin wax or pressure is good and strong enough to hold the material in place floor paste wax rubbed on the round guide rod and on the vertical while you do your drilling. steps in the back of the guides will make them move freely. Basic Standard Step Three: Drill Stop Collar Setting Setting the drill bit stop collar posi- tion is the easiest part of the en- tire process. Just drop the drill bit Mini through the guide bushing allowing the point to rest on the base of the jig. Slide the stop collar over the shank of the drill bit and allow it to rest on the top of the guide bush- ing. Lock in place with the appro- priate hex wrench supplied in the kit. -

Model G9749 Variable Speed Drill Press Owner's Manual

MODEL G9749 VARIABLE SPEED DRILL PRESS OWNER'S MANUAL COPYRIGHT © SEPTEMBER, 2006 BY GRIZZLY INDUSTRIAL, INC. WARNING: NO PORTION OF THIS MANUAL MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY SHAPE OR FORM WITHOUT THE WRITTEN APPROVAL OF GRIZZLY INDUSTRIAL, INC. #TS8502 PRINTED IN TAIWAN ����������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������������������ �������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� �� ���������������������������� �� ������������������������������������������������������������������ �� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������