Mud, Sweat and Tears Is a Must-Read for Adrenalin Junkies and Armchair Adventurers Alike

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SES Scientific Explorer Annual Review 2020.Pdf

SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER Dr Jane Goodall, Annual Review 2020 SES Lifetime Achievement 2020 (photo by Vincent Calmel) Welcome Scientific Exploration Society (SES) is a UK-based charity (No 267410) that was founded in 1969 by Colonel John Blashford-Snell and colleagues. It is the longest-running scientific exploration organisation in the world. Each year through its Explorer Awards programme, SES provides grants to individuals leading scientific expeditions that focus on discovery, research, and conservation in remote parts of the world, offering knowledge, education, and community aid. Members and friends enjoy charity events and regular Explorer Talks, and are also given opportunities to join exciting scientific expeditions. SES has an excellent Honorary Advisory Board consisting of famous explorers and naturalists including Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Dr Jane Goodall, Rosie Stancer, Pen Hadow, Bear Grylls, Mark Beaumont, Tim Peake, Steve Backshall, Vanessa O’Brien, and Levison Wood. Without its support, and that of its generous benefactors, members, trustees, volunteers, and part-time staff, SES would not achieve all that it does. DISCOVER RESEARCH CONSERVE Contents 2 Diary 2021 19 Vanessa O’Brien – Challenger Deep 4 Message from the Chairman 20 Books, Books, Books 5 Flying the Flag 22 News from our Community 6 Explorer Award Winners 2020 25 Support SES 8 Honorary Award Winners 2020 26 Obituaries 9 ‘Oscars of Exploration’ 2020 30 Medicine Chest Presentation Evening LIVE broadcast 32 Accounts and Notice of 2021 AGM 10 News from our Explorers 33 Charity Information 16 Top Tips from our Explorers “I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward.” Mark Beaumont, SES Lifetime Achievement 2018 and David Livingstone SES Honorary Advisory Board member (photo by Ben Walton) SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER > 2020 Magazine 1 Please visit SES on EVENTBRITE for full details and tickets to ALL our events. -

Forbes.Com - Magazine Article

Forbes.com - Magazine Article http://www.forbes.com/global/2003/1027/026_print.html Companies & Strategies Joann Muller, 10.27.03 Disney's 4-D technology aims to take the adventure out of building roller coasters. Get this: In the middle of sun-drenched Orlando, Fla. the Walt Disney Co. is erecting a 60-meter-high replica of snow-covered Mount Everest. It's a showcase attraction scheduled to open in 2006 at Disney's Animal Kingdom theme park. The premise: Visitors board an old mountain railway headed to the foot of Mount Everest. As the train climbs higher into "the Himalayas," it passes thick bamboo forests, thundering waterfalls and shimmering glacier fields. But the track ends unexpectedly in a gnarled mass of twisted metal. Suddenly the train begins racing forward and backward through caverns and icy canyons until riders come face to face with a giant hairy creature--the mythical yeti. It's enough to scare the wits out of Don W. Goodman, who has the job of ensuring that the $100 million roller coaster is finished on time--and on budget. It is a logistical nightmare: Hundreds of workers from independent contractors must simultaneously build the roller coaster and the mountain that contains it. They will erect 1,200 tons of steel and install one and a half hectares of rockwork. Goodman, president of Disney's Imagineering research lab, compares it to assembling a 3-D puzzle. It is difficult to anticipate the conflicts that will arise, say, between workers installing faux rock formations and crane operators erecting steel tracks. -

2012Bibarxiuizardfllibres Per

BIBLIOTECA ARXIU IZARD-LLONCH FORRELLAD DE LLEIDA 1 de 82. 21/05/2012 GRAL. X TITOL. Arxiu IZARD FORRELLAD. "Biblioteca" t/v Vol. AUTOR EDITORIAL Lloc Any Pags Fots Graf Maps Idioma Lleida 1949(I-IX), 1950(I-XII), 1951(I-XII) i 1952(I-XII+esp) t 1949 a 1952 CIUDAD LLEIDA 1949 castellà RomBeat rev Les pintures murals de Mur a la col.lecció Plandiura W 28 oct 1919, ed. tarda, pàg 6 La Veu de Catalunya Barcelona 1919 CATALÀ lleida rev AU VIGNEMALE. Les grottes du comte Russell dans les Pyrénées t A. de L. ILLUSTRATION, L' Paris 1898 2 10 FRENCH RomBeat La Batalla del Adopcionismo. t ABADAL i VINYALS/MILLÀS R Acad Buenas Letras de Barcelona 1949 190 0 castellà Osca DE NUESTRA FABLA t ABALOS, J. URRIZA, Lib y Enc de R. LLEIDA 64 0 castellà Lleida ELS PIRINEUS I LA FOTOGRAFIA t ABEL,Ton i JMª Sala Alb Novaidea Barcelona 2004 60 104 CATALÀ Lleida NOTES PER A LA HISTÒRIA DE PUIGCERCÓS t 7 Abella/Armengol/Català/PR GARSINEU EDICIONS TREMP 1992 93 40 div CATALÀ Lleida EL PALLARS REVISITAT. .... J.Morelló..... t 5 Abella/Cuenca/Ros/Tugues GARSINEU EDICIONS TREMP 2002 36 83 CATALÀ Lleida CATÀLEG de Bitllets dels Ajuntaments Catalans, 1936-38 t ABELLÓ/VIÑAS Auto Edició Reus/Barna 1981 102 0 molts CATALÀ Lleida EL INDICE DE PRIVILEGIOS DEL VALLE DE ARAN t ABIZANDA, Manel Institut Estudis Ilerdencs Balaguer 1944 85 3 castellà Arreu JANNU t ABREGO, Mari ARAMBURU IRUNEA 1982 132 +++ + castellà Arreu EN LA CIMA K-2 / CHOGOLISA t ABREGO/ARIZ KAIKU IRUNEA 1987 117 +++ castellà Osca Tras las Huellas de Lucien Briet. -

Renowned Adventurer Breaks Everest Record with World's Highest Dinner Party

Press release – May 2018 RENOWNED ADVENTURER BREAKS EVEREST RECORD WITH WORLD’S HIGHEST DINNER PARTY ON 30TH APRIL 2018 AT 7020M ABOVE SEA-LEVEL, EXPERIENCED BRITISH ADVENTURER NEIL LAUGHTON HAS BROKEN A WORLD RECORD TO HOST THE WORLD’S HIGHEST BLACK TIE DINNER PARTY AT THE NORTH COL ON THE TIBETAN SIDE OF MOUNT EVEREST.. The World’s Highest Dinner Party team led by adventurer Neil Laughton climbed to Mount Everest’s North Col (7020m/23031ft), where they set up a dining table, crockery, cutlery, a flower arrangement and Mumm champagne and then cooked an exclusive high-altitude menu, designed by Sat Bains, a Michelin two-starred chef. Dining on a menu specially designed to tantalise the taste buds at high altitude with the five flavours of salt, sweet, sour, bitter and umami the dinner party enjoyed a toast of Mumm champagne, miso soup, lamb tagine and the RSB Chocolate Bar. The team toasted the occasion with a bespoke cocktail created by exploration bar Mr Fogg’s and METAXA 12 Stars. The team raised a glass of Mumm champagne continuing Maison Mumm’s rich longstanding heritage in support of exploration and adventure. Press release – May 2018 The expedition repeated their 2015 route approaching Everest Expedition leader Neil Laughton said “I am delighted to have from the northern base camp in Tibet, following the Rongbuk succeeded in leading a British team in setting a rather eccentric Glacier up to Advance Base Camp at about 6,400m (21,000ft). The new world record – our next goal is to surpass our £150,000 for dinner took place at North Col, at 7,020m (23,032ft) which is close struggling Sherpa communicates after the devastating earthquake to the ‘death zone’. -

Log in at Explorermag.Org

TEACHER'S GUIDE NATGEO.ORG/EXPLORERMAG | VOL. 19 NO. 3 Pathfinder and Adventurer ’ C H O I C S S R E M E A H W C A A R E D Vol. 19 No. 3 T FOR THE CLASSROOM L E 2019 E A I N R Z N I A N G ® M A G IN THIS GUIDE: About the Learning Framework ���������2 Language Arts Lesson and Think Sheet������������������3–7 Expedition Everest Science Lesson and BLM ����������������8–9 Escape on the Pearl Social Studies Lesson and BLM ��10–11 en times during ember– , 1145 17th er: River of Ice x 291875, Science Lesson and BLM ������������ 12-13 age paid at EVEREST2 es. The Pearl 8 Article Tests �������������������������������� 14-16 Glaciers 16 Answer Key ������������������������������������17w Educational consultant Stephanie Harvey has helped shape the instructional vision for this Teacher's Guide. Her goal is to ensure you have the tools you need to enhance student understanding and engagement with nonfiction text. AD NOVDEC 2019 draft 6.indd 1 9/12/19 3:53 PM Lexile® Framework Levels Standards Supported Pathfinder • Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Expedition Everest ............................................ 710 • Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Escape on the Pearl .......................................... 730 • C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards (C3) River of Ice ........................................................ 690 See each lesson for the specific standard covered. Adventurer Expedition Everest ............................................ 920 Escape on the Pearl .......................................... 850 Looking for a fun way to test your student's River of Ice ........................................................ 800 recall? Each story in this issue of Explorer has an accompanying Kahoot! quiz. Log in at ExplorerMag.org • Interactive Digital Magazine with videos and activities to access additional resources including: • Projectable PDF for one-to-one instruction National Geographic Explorer, Pathfinder/Adventurer Page 1 Vol. -

Expedition Everest 2004 & 2005

A L G O N Q U I N C O L L E G E Small World Big Picture Expedition Everest 2004 & 2005 “A Season on Everest” Articles Published in the Ottawa Citizen 21st March 2004 – 29th June 2004 8th March 2005 – 31st May 2005 Back into thin air: Ben Webster is back on Mount Everest, determined to get his Canadian team to the top By Ron Corbett Sunday, March 21, 2004 Page: C5 (Weekly Section) The last time Ben Webster stood on the summit of Mount Everest, the new millennium had just begun. He stepped onto the roof of the world with Nazir Sabir, a climber from Pakistan, and stared at the land far below. The date was May 17, 2000. Somewhere beneath him, in a camp he could not see, were the other members of the Canadian Everest Expedition, three climbers from Quebec who would not reach the summit of the world's tallest mountain. As Webster stood briefly on the peak -- for no one stays long on that icy pinnacle -- stories were already circulating he had left the other climbers behind, so driven was he to become the first Canadian of the new millennium to reach the top of Everest. He would learn of the stories later, and they would sting. Accusation followed nasty accusation, the worst perhaps being that the other climbers had quit on him, so totalitarian had they found his leadership. When Webster descended from the mountain, he walked into a firestorm of negative publicity that bothers him to this day. At times in the ensuing four Julie Oliver, The Citizen's Weekly Shaunna Burke, a U of O doctoral student, Andrew Lock, an Australian, years he would shrug, and say simply he was the and Hector Ponce de Leon, of Mexico, will attempt a team assault on strongest of the four climbers, the only one able to Everest in May, led by Ottawa climber Ben Webster. -

SES's Scientific Explorer Annual Review 2018

SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 Expeditions, news and events DISCOVER Pioneers with Purpose RESEARCHExplorer Talks Hotung Award for Women’s Exploration 2018, Emily Penn, eXXpedition (North Pacific leg 1, Hawaii to Vancouver) CONSERVE Photo by Larkrise Pictures Welcome Scientific Exploration Society (SES) is a UK based charity (No 267410) that was founded in 1969 by Colonel John Blashford- Snell OBE. SES leads, funds and supports scientific discovery, research and conservation in remote parts of the world offering knowledge, education and community aid. Whilst few areas of the world remain undiscovered, there is still much to learn and to be done in promoting sustainable economies, saving endangered species and offering community welfare in less developed countries. Our focus today is on supporting young explorers through our Explorer Awards programme, building a community of like- minded individuals through the Society’s membership, offering regular explorer talks and providing opportunities to go on expeditions. We have an excellent Honorary Advisory Board, which includes Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Rosie Stancer, Pen Hadow, Ben Fogle, Bear Grylls, Mark Beaumont and Levison Wood. Without its support, and that of our Trustees, part-time staff and volunteers, SES would struggle to do all that it does. “Some have physical courage but lack the moral type, however I have not met any morally courageous people who lack the physical sort. Explorers need both types.” Colonel John Blashford-Snell OBE Contents 2 Diary 2019 18 Explorer Talks 2018 -

Catalogue 43: March 2011

Top of the World Books Catalogue 43: March 2011 Mountaineering Breashears and Salkeld, experts in historical mountaineering and Everest, examine the story of George Mallory, and his three expeditions to explore and [AAC]. Accidents in North American Mountaineering 2010. #25624, $12.- climb Everest, who along with Andrew Irvine disappeared in 1924. This [AAC]. American Alpine Club Journal 2010. #25550, $35.- wonderful book includes many vintage photographs, many of which have never been published, as well as images from the 1999 Mallory & Irvine Research Alpinist 33. Winter 2010-11. #25623, $10.99 Expedition which discovered Mallory’s body. Ament, Pat. Climbing Everest: A Meditation on Mountaineering and the Bremer-Kamp, Cherie. Living on the Edge. 1987 Smith, Layton, 1st, 8vo, st Spirit of Adventure. 2001 US, 1 , 8vo, pp.144, 37 illus, blue cloth; dj & cloth pp.213, photo frontis, 33 color photos, 4 maps, appendices, blue cloth; inscribed, new. #20737, $17.95 $16.15 dj fine, cloth fine. #25679, $35.- This is a new, hardcover edition of ‘10 Keys to Climb Everest’. Account of the 1985 first winter attempt on Kanchenjunga’s north face on which Bagley, Laurie. Summit! One Woman’s Mount Everest Climb Guides You Chris Chandler died. Signed copies of this book are unusual as Cherie lost all to Success. 2010 US, 1st, 8vo, pp.xi, 146, 5 bw photos, wraps; signed, new. of her fingers and toes following her tragic climb. #25621, $15.95 Cassin, Riccardo. La Sud del McKinley Alaska ‘61. 1965 Stampa Grafic Bagley, a part-time guide for Adventures International, has climbed Everest, Olimpia, Milano, 1st, 4to, pp.151, 14 color & 67 bw photos, map, gilt-dec Denali, Aconcagua, and Kilimanjaro. -

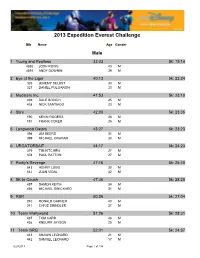

2013 Expedition Everest Challenge

2013 Expedition Everest Challenge Bib Name Age Gender Male 1 Young and Restless 33:33 5k: 19:14 4592 JOSH ROWE 43 M 4591 ANDY DOWNIN 39 M 2 Eye of the Liger 40:13 5k: 22:24 326 JEREMY SELBST 33 M 327 DANIEL PULGARON 33 M 3 Mudsters Inc. 41:53 5k: 23:10 439 DALE BOVICH 25 M 438 NICK SANTIAGO 23 M 4 Stirs 42:00 5k: 23:35 190 KEVIN ROGERS 36 M 191 FRANK COKER 35 M 5 Longwood Gators 43:27 5k: 23:23 398 JIM BEERS 31 M 399 MICHAEL GRAHAM 30 M 6 URGATORBAIT 44:17 5k: 24:23 379 TIM KITCHEN 27 M 378 PAUL PATTON 27 M 7 Porky's Revenge 47:16 5k: 26:40 543 HENRY LUGO 30 M 542 JUAN VIDAL 32 M 8 5K-to-Couch 47:36 5k: 28:28 457 DAMON KEITH 34 M 456 MICHAEL SWICKARD 31 M 9 R&R 50:36 5k: 27:04 240 RONALD GARNER 40 M 241 CHRIS SHINDLER 37 M 10 Team Wallyworld 51:26 5k: 28:31 437 TOM CARR 46 M 436 KNEURR JAYSON 25 M 11 Team SRQ 52:01 5k: 24:37 443 SHAWN LEONARD 21 M 442 SAMUEL LEONARD 17 M 5/29/2013 Page 1 of 134 2013 Expedition Everest Challenge Bib Name Age Gender 12 Wii Not Fit 52:41 5k: 28:31 566 JOSEPH MILLER 30 M 567 RONEEL BALROOP 32 M 13 Runners In-Law 53:59 5k: 25:02 335 SHEA SMITH 33 M 334 NICK DEBELLIS 31 M 14 Team Cornerstone 54:16 5k: 27:22 488 ALLAN BECK 50 M 489 ROBERT WINSLOW 32 M 15 SilverMason 55:04 5k: 28:20 978 ERIC SILVERMAN 46 M 979 JEFFREY MASON 38 M 16 Ears to You!!! 55:29 5k: 30:21 1409 ALEXANDER ZIELINSKI 20 M 1408 RICHARD ZIELINSKI 58 M 17 Team Trike 56:22 5k: 28:25 798 RYAN TREICHLER 38 M 799 NOAH TREICHLER 11 M 18 Like Father Like Son 57:17 5k: 28:53 3602 DANIEL VEGA 54 M 3603 MICHAEL VEGA 31 M 19 Gmen 58:12 5k: 32:36 959 WAYNE -

A4 Cewe Mag 2016 Winter.Indd

WINTER 2016 cewe magazine My Life, My Photos czyńska FEATURING The winning entry of Our World Is Beautiful 2015, Agnieszka Gul Everest Explorer Our World Is Beautiful The Perfect Gift Adventurer Neil Laughton shares Your favourite photography Make them smile with a his incredible stories p14 competition is back p19 CEWE PHOTOBOOK p06 www.cewe-photoworld.com >>> CONTENTS > < CONTENTS <<< 06 Software Secrets 22 CONTENTS 24 The fantastic things you didn’t know you could do with our software CEWE MAGAZINE - SUMMER ISSUE 2016 Editorial Team and Queries: [email protected] Future Favourites 26 A sneak peek of what’s in the pipeline at CEWE CEWE News 04 The latest news from CEWE UK. CEWE PHOTOBOOK Partners 27 The partners who proudly off er the The Perfect Gift, Made By You 08 CEWE PHOTOBOOK 06 Treat someone special to a CEWE PHOTOBOOK DIY Photo Fun A Whole New World 18 28 Time to get creative with your snaps 08 Kimberley Coole on the transition from travel to baby photography Print by Numbers 30 The facts and fi gures behind Europe’s number one photo book Create a Book of Your Year 12 Share the story of the past 12 months in a Customer Support CEWE PHOTOBOOK 31 How to contact our friendly team Adventurer Extraordinaire 12 14 Explorer Neil Laughton tells us about his life of adventure Welcome This time of year off ers the perfect Rainy Day Photo Tips opportunity to look back over the 18 Don’t let a downpour stop you getting out there personal memories and moments with your camera of the last 12 months. -

Proud to Support Bangor Grammarians

PROUD TO SUPPORT BANGOR GRAMMARIANS. TALK TO US ABOUT THE THINGS YOU NEED FROM YOUR BANK BRANCH. PHONE. ONLINE. First Trust Bank is a trade mark of AIB Group (UK) p.l.c. (a wholly owned subsidiary of Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c.), incorporated in Northern Ireland. Registered Office 92 Ann Street, Belfast, BT1 3HH. Registered Number NI018800. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority. 2 www.grammarians.co.uk Chairman’s Message Geoffrey Miller Fellow Grammarians, This is my third and final letter to you as Chairman of the Association and so, if I may be forgiven for taking a little time to reflect on my time in office, I am pleased to say it has coincided with significant advancements for the school we are proud to call our alma mater. You will see from the Principal’s Report that whilst this year has been the most challenging in recent memory, with the tragic deaths of two fine pupils and a regarded staff member too, the reaction of the whole school family has shown it in the finest light. This was probably best exemplified by the wonderful fundraising night organised by Year 14 in memory of Peter Clarke. It was a truly inspirational event and one that evoked a real sense of community. It is hard to believe, but nonetheless true, that the current Year 12 pupils (5th Form in old money!) have known no other school than that at the Gransha Road site. For those Retired Archivist Barry Greenaway (left) receives a Grammarians boys and the generations to follow, it will be the focus Plaque from outgoing Chairman Geoffrey Miller of their memories in the same way the Clifton Road and College Avenue sites in all their glory are for those of us from hoped this can be extended in the coming months and years an earlier time. -

Sir Edmund Hillary 2.5 Degrees Celsius in the Past 50 Years, and Month

The James Caird Society Newsletter Issue 14 · July 2008 Antarctic ice shelf continues to break up Inside this issue Pages 2–3 News from the James Caird Society, including ‘Some presidential outings’ Pages 4–5 Polar News, including the Christie’s 2007 sale of some Shackleton letters Page 6 Tim Jarvis gives an update on the Shackleton Epic Expedition Page 7 Lt Col Henry Worsley on the Shackleton Centenary Expedition, 2008 Site of the former Larsen-B Ice Shelf and the Antarctic Peninsula. Pages 8–9 A giant Antarctic ice shelf that began to break up in February is shedding Author John Gimlette on ‘The Other End of the ice despite the approach of winter, according to the European Space Agency. Atlantic’ The break-up is the latest sign that warmer In 2002, the Larsen-B Ice Shelf col- Page 10 temperatures are affecting the Antarctic lapsed, with 453 billion tonnes of ice A tribute to the late Peninsula. The peninsula has warmed about breaking up into icebergs in less than a Sir Edmund Hillary 2.5 degrees Celsius in the past 50 years, and month. seven ice shelves have retreated or disinte- Other shelves that have collapsed in the Page 11 grated in the past two decades, ESA said. past 30 years include Prince Gustav Chan- On David Tatham’s new About 160km2 broke off the shelf in late nel, Larsen Inlet, Larsen A, Wordie, Muller Dictionary of Falklands May, the first documented calving of ice in and Jones. Biography winter. The shelf’s link between Charcot While the Antarctic Peninsula is losing and Latady islands more than halved to ice, the Antarctic Ice Sheet as a whole will Pages 12–13 2.7km and now risks breaking completely, remain ‘too cold for surface melting and is Sir Wally Herbert, explorer and polar artist, remembered said ESA, which monitors the region by expected to gain in mass due to increased satellite.