Soviet Mountaineers and Mount Everest, 1953–1960 Eva Maurer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moüjmtaiim Operations

L f\f¿ áfó b^i,. ‘<& t¿ ytn) ¿L0d àw 1 /1 ^ / / /This publication contains copyright material. *FM 90-6 FieW Manual HEADQUARTERS No We DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 30 June 1980 MOÜJMTAIIM OPERATIONS PREFACE he purpose of this rUanual is to describe how US Army forces fight in mountain regions. Conditions will be encountered in mountains that have a significant effect on. military operations. Mountain operations require, among other things^ special equipment, special training and acclimatization, and a high decree of self-discipline if operations are to succeed. Mountains of military significance are generally characterized by rugged compartmented terrain witn\steep slopes and few natural or manmade lines of communication. Weather in these mountains is seasonal and reaches across the entireSspectrum from extreme cold, with ice and snow in most regions during me winter, to extreme heat in some regions during the summer. AlthoughNthese extremes of weather are important planning considerations, the variability of weather over a short period of time—and from locality to locahty within the confines of a small area—also significantly influences tactical operations. Historically, the focal point of mountain operations has been the battle to control the heights. Changes in weaponry and equipment have not altered this fact. In all but the most extreme conditions of terrain and weather, infantry, with its light equipment and mobility, remains the basic maneuver force in the mountains. With proper equipment and training, it is ideally suited for fighting the close-in battfe commonly associated with mountain warfare. Mechanized infantry can\also enter the mountain battle, but it must be prepared to dismount and conduct operations on foot. -

K2 Base Camp and Gondogoro La Trek

K2 And Gondogoro La Trek, Pakistan This is a trekking holiday to K2 and Concordia in the Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan followed by crossing the Gondogoro La to Hushe Valley to complete a superb mountaineering journey. Group departures See trip’s date & cost section Holiday overview Style Trek Accommodation Hotels, Camping Grade Strenuous Duration 23 days from Islamabad to Islamabad Trekking / Walking days On Trek: 15 days Min/Max group size 1 / 8. Guaranteed to run Meeting point Joining in Islamabad, Pakistan Max altitude 5,600m, Gondogoro Pass Private Departures & Tailor Made itineraries available Departures Group departures 2021 Dates: 20 Jun - 12 Jul 27 Jun - 19 Jul 01 Jul - 23 Jul 04 Jul - 26 Jul 11 Jul - 02 Aug 18 Jul - 09 Aug 25 Jul - 16 Aug 01 Aug - 23 Aug 08 Aug - 30 Aug 15 Aug - 06 Sep 22 Aug - 13 Sep 29 Aug - 20 Sep Will these trips run? All our k2 and Gondogoro la treks are guaranteed to run as schedule. Unlike some other companies, our trips will take place with a minimum of 1 person and maximum of 8. Best time to do this Trek Pakistan is blessed with four season weather, spring, summer, autumn and winter. This tour itinerary is involved visiting places where winter is quite harsh yet spring, summer and autumns are very pleasant. We recommend to do this Trek between June and September. Group Prices & discounts We have great range of Couple, Family and Group discounts available, contact us before booking. K2 and Gondogoro trek prices are for the itinerary starting from Islamabad to Skardu K2 - Gondogoro Pass - Hushe Valley and back to Islamabad. -

Forbes.Com - Magazine Article

Forbes.com - Magazine Article http://www.forbes.com/global/2003/1027/026_print.html Companies & Strategies Joann Muller, 10.27.03 Disney's 4-D technology aims to take the adventure out of building roller coasters. Get this: In the middle of sun-drenched Orlando, Fla. the Walt Disney Co. is erecting a 60-meter-high replica of snow-covered Mount Everest. It's a showcase attraction scheduled to open in 2006 at Disney's Animal Kingdom theme park. The premise: Visitors board an old mountain railway headed to the foot of Mount Everest. As the train climbs higher into "the Himalayas," it passes thick bamboo forests, thundering waterfalls and shimmering glacier fields. But the track ends unexpectedly in a gnarled mass of twisted metal. Suddenly the train begins racing forward and backward through caverns and icy canyons until riders come face to face with a giant hairy creature--the mythical yeti. It's enough to scare the wits out of Don W. Goodman, who has the job of ensuring that the $100 million roller coaster is finished on time--and on budget. It is a logistical nightmare: Hundreds of workers from independent contractors must simultaneously build the roller coaster and the mountain that contains it. They will erect 1,200 tons of steel and install one and a half hectares of rockwork. Goodman, president of Disney's Imagineering research lab, compares it to assembling a 3-D puzzle. It is difficult to anticipate the conflicts that will arise, say, between workers installing faux rock formations and crane operators erecting steel tracks. -

Age of Crystallization and Cooling of the K2 Gneiss in the Baltoro

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 147, 1990, pp. 603-606, 3 figs 2 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland SHORT PAPER evidence of Precambrian inheritance (Parrish & Tirrull989). Earlier pre-collision granites within theKarakoram Age of crystallization and cooling of the batholith include the Muztagh Tower unit (Fig. 1) composed K2 gneiss in the Baltoro Karakoram of biotite and hornblende-rich foliated granodiorites, which gave three K-Ar hornblende ages spanning 82-75 f 3 Ma M.P. SEARLE', R. R. PARRISH', (Searle et al. 1989), and the Hushegneiss, SE of the Baltoro R.TIRRUL** & D.C. REX3 area, which has a U-Pb zircon age of 145 f 5 Ma and two 'Department of Earth Sciences, Oxford University, 40Ar-39Arages of 203 f 0.6 Ma and 204 f 1.4 Ma (Searle et Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PR al. 1989). Further west,hornblende-bearing granodiorites 'Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, from the Hunza plutonic unit gave a U-Pb age of 95 f 4 Ottawa, Canada KlA OE8 (LeFort et al. 1983) and similar granites at the Darkot Pass Department of Earth Sciences, Leeds University, gave a Rb-Sr isochron age of 111 f 6 (Debon et al. 1987). Leeds, LS2 9JT These pre-collision granites of the Karakoram batholith all have calc-alkaline geochemical affinities and have been interpretedas Andean-type granitesalong thesouthern continental margin of the Asian plate, related to the Themountains of K2 (8611 m)and Broad Peak (8047111) in the northward subduction of Tethyan oceanic crust (LeFort et Baltoro (northernPakistan) are composedof Karakoram al. -

2012Bibarxiuizardfllibres Per

BIBLIOTECA ARXIU IZARD-LLONCH FORRELLAD DE LLEIDA 1 de 82. 21/05/2012 GRAL. X TITOL. Arxiu IZARD FORRELLAD. "Biblioteca" t/v Vol. AUTOR EDITORIAL Lloc Any Pags Fots Graf Maps Idioma Lleida 1949(I-IX), 1950(I-XII), 1951(I-XII) i 1952(I-XII+esp) t 1949 a 1952 CIUDAD LLEIDA 1949 castellà RomBeat rev Les pintures murals de Mur a la col.lecció Plandiura W 28 oct 1919, ed. tarda, pàg 6 La Veu de Catalunya Barcelona 1919 CATALÀ lleida rev AU VIGNEMALE. Les grottes du comte Russell dans les Pyrénées t A. de L. ILLUSTRATION, L' Paris 1898 2 10 FRENCH RomBeat La Batalla del Adopcionismo. t ABADAL i VINYALS/MILLÀS R Acad Buenas Letras de Barcelona 1949 190 0 castellà Osca DE NUESTRA FABLA t ABALOS, J. URRIZA, Lib y Enc de R. LLEIDA 64 0 castellà Lleida ELS PIRINEUS I LA FOTOGRAFIA t ABEL,Ton i JMª Sala Alb Novaidea Barcelona 2004 60 104 CATALÀ Lleida NOTES PER A LA HISTÒRIA DE PUIGCERCÓS t 7 Abella/Armengol/Català/PR GARSINEU EDICIONS TREMP 1992 93 40 div CATALÀ Lleida EL PALLARS REVISITAT. .... J.Morelló..... t 5 Abella/Cuenca/Ros/Tugues GARSINEU EDICIONS TREMP 2002 36 83 CATALÀ Lleida CATÀLEG de Bitllets dels Ajuntaments Catalans, 1936-38 t ABELLÓ/VIÑAS Auto Edició Reus/Barna 1981 102 0 molts CATALÀ Lleida EL INDICE DE PRIVILEGIOS DEL VALLE DE ARAN t ABIZANDA, Manel Institut Estudis Ilerdencs Balaguer 1944 85 3 castellà Arreu JANNU t ABREGO, Mari ARAMBURU IRUNEA 1982 132 +++ + castellà Arreu EN LA CIMA K-2 / CHOGOLISA t ABREGO/ARIZ KAIKU IRUNEA 1987 117 +++ castellà Osca Tras las Huellas de Lucien Briet. -

Your Beautiful Baltistan Holiday Experience

YOUR BEAUTIFUL BALTISTAN HOLIDAY EXPERIENCE Royal Palaces, Fortresses, Adventure and the Authentic Baltistan! – 9 days EXPERIENCE SERENA HOTELS. EXPERIENCE GILGIT-BALTISTAN BEAUTIFUL BALTISTAN! THE FACTS ü Inhabited by the Balti people who are of Tibetan descent Baltistan is a remote and beautiful land spread over 26,227 km2 in the north of Pakistan. It ü Official language Balti & Urdu borders Ladakh to the East, Kashmir to the South, and Sinkiang province of China to the nd North. It has the most awe inspiring landscape with breath taking scenes of the Karakoram ü Contains the highest mountains in the Karakorum’s, including the worlds 2 highest mountain, K2 mountain range, sublime & picturesque terraced fields, the worlds 2nd highest mountain K2, ü Officially named Gilgit-Baltistan in 2009 (formerly Northern Areas) some of the world’s largest glaciers outside of the North & South poles and the world’s ü The capital is Skardu largest high altitude plateau - the Deosai Plains. ü Key Industries: Subsistence farming, animal husbandry, gems mining & tourism In addition to its amazing natural beauty Baltistan is rich & diverse in history and culture. Its historical treasures include forts, palaces, mosques, and archeological treasures such as THE TRIVIA Buddha stupa’s and thousands of ancient petrolglyphs (rock carvings). Due to its isolation ü Locals call Baltistan Batli-yul from the rest of Pakistan Baltistan has not developed at the dramatic pace of its neighbouring ü Pakistan is home to 108 peaks over 7,000 meters with most of these mountains located in Baltistan provinces and has managed to preserve its culture adding to its charm and character. -

Log in at Explorermag.Org

TEACHER'S GUIDE NATGEO.ORG/EXPLORERMAG | VOL. 19 NO. 3 Pathfinder and Adventurer ’ C H O I C S S R E M E A H W C A A R E D Vol. 19 No. 3 T FOR THE CLASSROOM L E 2019 E A I N R Z N I A N G ® M A G IN THIS GUIDE: About the Learning Framework ���������2 Language Arts Lesson and Think Sheet������������������3–7 Expedition Everest Science Lesson and BLM ����������������8–9 Escape on the Pearl Social Studies Lesson and BLM ��10–11 en times during ember– , 1145 17th er: River of Ice x 291875, Science Lesson and BLM ������������ 12-13 age paid at EVEREST2 es. The Pearl 8 Article Tests �������������������������������� 14-16 Glaciers 16 Answer Key ������������������������������������17w Educational consultant Stephanie Harvey has helped shape the instructional vision for this Teacher's Guide. Her goal is to ensure you have the tools you need to enhance student understanding and engagement with nonfiction text. AD NOVDEC 2019 draft 6.indd 1 9/12/19 3:53 PM Lexile® Framework Levels Standards Supported Pathfinder • Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Expedition Everest ............................................ 710 • Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Escape on the Pearl .......................................... 730 • C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards (C3) River of Ice ........................................................ 690 See each lesson for the specific standard covered. Adventurer Expedition Everest ............................................ 920 Escape on the Pearl .......................................... 850 Looking for a fun way to test your student's River of Ice ........................................................ 800 recall? Each story in this issue of Explorer has an accompanying Kahoot! quiz. Log in at ExplorerMag.org • Interactive Digital Magazine with videos and activities to access additional resources including: • Projectable PDF for one-to-one instruction National Geographic Explorer, Pathfinder/Adventurer Page 1 Vol. -

Expedition Everest 2004 & 2005

A L G O N Q U I N C O L L E G E Small World Big Picture Expedition Everest 2004 & 2005 “A Season on Everest” Articles Published in the Ottawa Citizen 21st March 2004 – 29th June 2004 8th March 2005 – 31st May 2005 Back into thin air: Ben Webster is back on Mount Everest, determined to get his Canadian team to the top By Ron Corbett Sunday, March 21, 2004 Page: C5 (Weekly Section) The last time Ben Webster stood on the summit of Mount Everest, the new millennium had just begun. He stepped onto the roof of the world with Nazir Sabir, a climber from Pakistan, and stared at the land far below. The date was May 17, 2000. Somewhere beneath him, in a camp he could not see, were the other members of the Canadian Everest Expedition, three climbers from Quebec who would not reach the summit of the world's tallest mountain. As Webster stood briefly on the peak -- for no one stays long on that icy pinnacle -- stories were already circulating he had left the other climbers behind, so driven was he to become the first Canadian of the new millennium to reach the top of Everest. He would learn of the stories later, and they would sting. Accusation followed nasty accusation, the worst perhaps being that the other climbers had quit on him, so totalitarian had they found his leadership. When Webster descended from the mountain, he walked into a firestorm of negative publicity that bothers him to this day. At times in the ensuing four Julie Oliver, The Citizen's Weekly Shaunna Burke, a U of O doctoral student, Andrew Lock, an Australian, years he would shrug, and say simply he was the and Hector Ponce de Leon, of Mexico, will attempt a team assault on strongest of the four climbers, the only one able to Everest in May, led by Ottawa climber Ben Webster. -

Catalogue 43: March 2011

Top of the World Books Catalogue 43: March 2011 Mountaineering Breashears and Salkeld, experts in historical mountaineering and Everest, examine the story of George Mallory, and his three expeditions to explore and [AAC]. Accidents in North American Mountaineering 2010. #25624, $12.- climb Everest, who along with Andrew Irvine disappeared in 1924. This [AAC]. American Alpine Club Journal 2010. #25550, $35.- wonderful book includes many vintage photographs, many of which have never been published, as well as images from the 1999 Mallory & Irvine Research Alpinist 33. Winter 2010-11. #25623, $10.99 Expedition which discovered Mallory’s body. Ament, Pat. Climbing Everest: A Meditation on Mountaineering and the Bremer-Kamp, Cherie. Living on the Edge. 1987 Smith, Layton, 1st, 8vo, st Spirit of Adventure. 2001 US, 1 , 8vo, pp.144, 37 illus, blue cloth; dj & cloth pp.213, photo frontis, 33 color photos, 4 maps, appendices, blue cloth; inscribed, new. #20737, $17.95 $16.15 dj fine, cloth fine. #25679, $35.- This is a new, hardcover edition of ‘10 Keys to Climb Everest’. Account of the 1985 first winter attempt on Kanchenjunga’s north face on which Bagley, Laurie. Summit! One Woman’s Mount Everest Climb Guides You Chris Chandler died. Signed copies of this book are unusual as Cherie lost all to Success. 2010 US, 1st, 8vo, pp.xi, 146, 5 bw photos, wraps; signed, new. of her fingers and toes following her tragic climb. #25621, $15.95 Cassin, Riccardo. La Sud del McKinley Alaska ‘61. 1965 Stampa Grafic Bagley, a part-time guide for Adventures International, has climbed Everest, Olimpia, Milano, 1st, 4to, pp.151, 14 color & 67 bw photos, map, gilt-dec Denali, Aconcagua, and Kilimanjaro. -

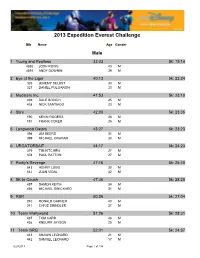

2013 Expedition Everest Challenge

2013 Expedition Everest Challenge Bib Name Age Gender Male 1 Young and Restless 33:33 5k: 19:14 4592 JOSH ROWE 43 M 4591 ANDY DOWNIN 39 M 2 Eye of the Liger 40:13 5k: 22:24 326 JEREMY SELBST 33 M 327 DANIEL PULGARON 33 M 3 Mudsters Inc. 41:53 5k: 23:10 439 DALE BOVICH 25 M 438 NICK SANTIAGO 23 M 4 Stirs 42:00 5k: 23:35 190 KEVIN ROGERS 36 M 191 FRANK COKER 35 M 5 Longwood Gators 43:27 5k: 23:23 398 JIM BEERS 31 M 399 MICHAEL GRAHAM 30 M 6 URGATORBAIT 44:17 5k: 24:23 379 TIM KITCHEN 27 M 378 PAUL PATTON 27 M 7 Porky's Revenge 47:16 5k: 26:40 543 HENRY LUGO 30 M 542 JUAN VIDAL 32 M 8 5K-to-Couch 47:36 5k: 28:28 457 DAMON KEITH 34 M 456 MICHAEL SWICKARD 31 M 9 R&R 50:36 5k: 27:04 240 RONALD GARNER 40 M 241 CHRIS SHINDLER 37 M 10 Team Wallyworld 51:26 5k: 28:31 437 TOM CARR 46 M 436 KNEURR JAYSON 25 M 11 Team SRQ 52:01 5k: 24:37 443 SHAWN LEONARD 21 M 442 SAMUEL LEONARD 17 M 5/29/2013 Page 1 of 134 2013 Expedition Everest Challenge Bib Name Age Gender 12 Wii Not Fit 52:41 5k: 28:31 566 JOSEPH MILLER 30 M 567 RONEEL BALROOP 32 M 13 Runners In-Law 53:59 5k: 25:02 335 SHEA SMITH 33 M 334 NICK DEBELLIS 31 M 14 Team Cornerstone 54:16 5k: 27:22 488 ALLAN BECK 50 M 489 ROBERT WINSLOW 32 M 15 SilverMason 55:04 5k: 28:20 978 ERIC SILVERMAN 46 M 979 JEFFREY MASON 38 M 16 Ears to You!!! 55:29 5k: 30:21 1409 ALEXANDER ZIELINSKI 20 M 1408 RICHARD ZIELINSKI 58 M 17 Team Trike 56:22 5k: 28:25 798 RYAN TREICHLER 38 M 799 NOAH TREICHLER 11 M 18 Like Father Like Son 57:17 5k: 28:53 3602 DANIEL VEGA 54 M 3603 MICHAEL VEGA 31 M 19 Gmen 58:12 5k: 32:36 959 WAYNE -

From: Lee Greenwald To

From: Lee Greenwald To: FS-objections-pnw-mthood Subject: Twilight Parking lot Date: Monday, March 03, 2014 11:44:20 PM Attachments: 2013 International Report on Snow Mountain Tourism.pdf Cross-country skiing experiencing a Nordic renaissance Olympian.pdf Twilight Parking Lot OBJECTION 3-1-14 EAE v2.doc Dear objections official, I previously raised several objections concerning Mt Hood Meadows application to build the Twilight Parking lot. Though some, not all, of these objections were ostensibly addressed in their responses, they were not addressed fully nor adequately. I raised concerns regarding Meadows assumptions on growth in demand for Alpine skiing. The last ten years MHM stated continued growth trends, but actually the most recent previous two years that has not been the trend. The true growth is in Nordic skiing. The majority of the Nordic community is against the creation of the Twilight lot without a comprehensive analysis of potential future use of this terrain, and nearby Nordic trails and connecting trails. This type of analysis has not been done, and would be precluded by proceeding with the construction of the Twilight lot before all future use options have been considered. Second, I asked that MHM be required by the FS to place the funds, $500,000, for a Nordic center in a designated account for a future Nordic center building, and a restrictive timeline for construction. If the parking lot is to be built, the Nordic community should have some prior input on the Nordic facility to be built prior to the lots final approval. The response that was posted simply stated that "a" facility would be built within three years. -

Muhammad Ali Sadpara an Anonymous Prince of the Mountains Anwar Ali1*, Munir Ahmed2 and Ahmed Bostani3

Saudi Journal of Medicine Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Med ISSN 2518-3389 (Print) |ISSN 2518-3397 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com Review Article Muhammad Ali Sadpara an Anonymous Prince of the Mountains Anwar Ali1*, Munir Ahmed2 and Ahmed Bostani3 1Dr. Anwar Ali, PhD-Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology, Central South University, Changsha City, Hunan, China 2Mr. Munir Ahmed, MPhil Scholar, Department of Food Science and Engineering, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China 3Mr. Ahmed Bostani, MPhil Scholar, Department of Tourism Management, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China DOI: 10.36348/sjm.2021.v06i02.004 | Received: 02.02.2021 | Accepted: 17.02.2021 | Published: 27.02.2021 *Corresponding Author: Anwar Ali Abstract Mountaineering is a field that is easy to see but very difficult, those who adopt this field are well aware that one day they may not be able to see the next day’s sun. It is also very attractive in the background of how dangerous it looks. The beauty of the mountain valleys can only be appreciated by one who has seen it up close and Muhammad Ali Sadpara was one of those lucky people. He was the prince of the mountains who hoisted the flag of his nation on the highest peaks of the world. He climbed eight of 14 Eight-thousanders. His first climb was Gasherbrum II in Karakoram. In this review we tried to explore the life of a mountaineer who sacrificed his life just for the sake of his nation and country.