Determinism and Meaningfulness in Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's Philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1936 The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Frederick Joseph, "The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy" (1936). Master's Theses. Paper 912. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. mE Dt:VEto!l..mm oa llS. At..~"1lr:D !JG'lt'fR ~!EREAli •a MiILOSO?ll' A. thesis SUbm1tte4 to the Gradus:te i'acnl ty in cana1:.at1: f!Jr tbe degree of llaste,-. of Arts Univerait7 of !llcuor.&a Jnno 1936 PREF!~CE The modern-·wr1 ter in the field of Philosophy no doubt recognises the ilfficulty of gaining an ndequate and impartial hearing from the students of his own generation. It seems that one only becomes great at tbe expense of deatb. The university student is often tempted to close his study of philosophy- after Plato alld Aristotle as if the final word has bean said. The writer of this paper desires to know somethi~g about the contribution of the model~n school of phiiiosophers. He has chosen this particular study because he believes that Dr. \i'hi tehesa bas given a very thoughtful interpretation of the universe .. This paper is in no way a substitute for a first-hand study of the works of Whitehead. -

At Least in Biophysical Novelties Amihud Gilead

The Twilight of Determinism: At Least in Biophysical Novelties Amihud Gilead Department of Philosophy, Eshkol Tower, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838 Email: [email protected] Abstract. In the 1990s, Richard Lewontin referred to what appeared to be the twilight of determinism in biology. He pointed out that DNA determines only a little part of life phenomena, which are very complex. In fact, organisms determine the environment and vice versa in a nonlinear way. Very recently, biophysicists, Shimon Marom and Erez Braun, have demonstrated that controlled biophysical systems have shown a relative autonomy and flexibility in response which could not be predicted. Within the boundaries of some restraints, most of them genetic, this freedom from determinism is well maintained. Marom and Braun have challenged not only biophysical determinism but also reverse-engineering, naive reductionism, mechanism, and systems biology. Metaphysically possibly, anything actual is contingent.1 Of course, such a possibility is entirely excluded in Spinoza’s philosophy as well as in many philosophical views at present. Kant believed that anything phenomenal, namely, anything that is experimental or empirical, is inescapably subject to space, time, and categories (such as causality) which entail the undeniable validity of determinism. Both Kant and Laplace assumed that modern science, such as Newton’s physics, must rely upon such a deterministic view. According to Kant, free will is possible not in the phenomenal world, the empirical world in which we 1 This is an assumption of a full-blown metaphysics—panenmentalism—whose author is Amihud Gilead. See Gilead 1999, 2003, 2009 and 2011, including literary, psychological, and natural applications and examples —especially in chemistry —in Gilead 2009, 2010, 2013, 2014a–c, and 2015a–d. -

Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman

17 Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman The Alpha Course, a well‐known evangelical Christian programme, advertises itself with posters displaying the words THE MEANING OF LIFE IS_________, followed by the invitation ‘Fill in the blanks at alpha.org’. Followers of the course will discover that ‘Men and women were created to live in a relationship with God’, and that ‘without that relationship there will always be a hunger, an emptiness, a feeling that something is missing’.1 We all have that need because we are all sinners, we are told, and the truth which will fill the need is that Jesus Christ died to save us from our sins. Not all Christian or other religious views about the meaning of life are as simplistic as this, but they typically share the assumptions that the meaning of life is to be found in some belief whose truth we need to recognize, and that this is a belief about the purpose for which we exist. A further implication is that this purpose is the purpose intended by the God who created us, and that if we fail to identify and live in accordance with that purpose, our lives will lack meaning. The assumption is echoed in the question many humanists will have encountered: if you don’t believe in a God, what’s the point of it all? And many people who don’t share the answer still accept the legitimacy of the question – ‘What is the meaning of life?’ – and assume that what we need is a correct belief, religious or non‐religious, which will fill the blank in the sentence ‘The meaning of life is …’. -

Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2014, 4, 231-243 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43031 Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy Niels Skovgaard Olsen Department of Philosophy, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany Email: [email protected] Received 25 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article takes its point of departure in a criticism of the views on meta-philosophy of P.M.S. Hacker for being too dismissive of the possibility of philosophical theory-construction. But its real aim is to put forward an explanatory hypothesis for the lack of a body of established truths and universal research programs in philosophy along with the outline of a positive account of what philosophical theories are and of how to assess them. A corollary of the present account is that it allows us to account for the objective dimension of philosophical discourse without taking re- course to the problematic idea of there being worldly facts that function as truth-makers for phi- losophical claims. Keywords Meta-Philosophy, Hacker, Williamson, Philosophical Theories 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to use a critical discussion of the self-image of philosophy presented by P. M. S. Hacker as a platform for presenting an alternative, which offers an account of how to think about the purpose and cha- racter of philosophical theories. -

Defending the Subjective Component of Susan Wolf's

Defending the Subjective Component of Susan Wolf’s “Fitting Fulfillment View” About Meaning in Life. Andreas Hjälmarö Andreas Hjälmarö Kandidatuppsats Filosofi, 15 hp. Ht 2016 Handledare Frans Svensson Umeå Universitet, Umeå Table of content Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Background ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 The question .................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Common answers .......................................................................................................................... 8 The nihilistic view ............................................................................................................................ 8 The super-naturalistic view ............................................................................................................. 8 The naturalistic view ....................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Wolf’s view – a combination ...................................................................................................... -

God As Both Ideal and Real Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics

God As Both Ideal and Real Being In the Aristotelian Metaphysics Martin J. Henn St. Mary College Aristotle asserts in Metaphysics r, 1003a21ff. that "there exists a science which theorizes on Being insofar as Being, and on those attributes which belong to it in virtue of its own nature."' In order that we may discover the nature of Being Aristotle tells us that we must first recognize that the term "Being" is spoken in many ways, but always in relation to a certain unitary nature, and not homonymously (cf. Met. r, 1003a33-4). Beings share the same name "eovta," yet they are not homonyms, for their Being is one and the same, not manifold and diverse. Nor are beings synonyms, for synonymy is sameness of name among things belonging to the same genus (as, say, a man and an ox are both called "animal"), and Being is no genus. Furthermore, synonyms are things sharing a common intrinsic nature. But things are called "beings" precisely because they share a common relation to some one extrinsic nature. Thus, beings are neither homonyms nor synonyms, yet their core essence, i.e. their Being as such, is one and the same. Thus, the unitary Being of beings must rest in some unifying nature extrinsic to their respective specific essences. Aristotle's dialectical investigations into Being eventually lead us to this extrinsic nature in Book A, i.e. to God, the primary Essence beyond all specific essences. In the pre-lambda books of the Metaphysics, however, this extrinsic nature remains very much up for grabs. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics Versus Science

To appear in Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2004) In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics versus Science F.A. Muller Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Mathematics Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.000 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] August 2003 Summary Over the past years, in books and journals (this journal included), N. Maxwell launched a ferocious attack on B.C. van Fraassen's view of science called Con- structive Empiricism (CE). This attack has been totally ignored. Must we con- clude from this silence that no defence is possible against the attack and that a fortiori Maxwell has buried CE once and for all, or is the attack too obviously flawed as not to merit exposure? We believe that neither is the case and hope that a careful dissection of Maxwell's reasoning will make this clear. This dis- section includes an analysis of Maxwell's `aberrance-argument' (omnipresent in his many writings) for the contentious claim that science implicitly and per- manently accepts a substantial, metaphysical thesis about the universe. This claim generally has been ignored too, for more than a quarter of a century. Our con- clusions will be that, first, Maxwell's attacks on CE can be beaten off; secondly, his `aberrance-arguments' do not establish what Maxwell believes they estab- lish; but, thirdly, we can draw a number of valuable lessons from these attacks about the nature of science and of the libertarian nature of CE. Table of Contents on other side −! Contents 1 Exordium: What is Maxwell's Argument? 1 2 Does Science Implicitly Accept Metaphysics? 3 2.1 Aberrant Theories . -

Causality and Determinism: Tension, Or Outright Conflict?

1 Causality and Determinism: Tension, or Outright Conflict? Carl Hoefer ICREA and Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona Draft October 2004 Abstract: In the philosophical tradition, the notions of determinism and causality are strongly linked: it is assumed that in a world of deterministic laws, causality may be said to reign supreme; and in any world where the causality is strong enough, determinism must hold. I will show that these alleged linkages are based on mistakes, and in fact get things almost completely wrong. In a deterministic world that is anything like ours, there is no room for genuine causation. Though there may be stable enough macro-level regularities to serve the purposes of human agents, the sense of “causality” that can be maintained is one that will at best satisfy Humeans and pragmatists, not causal fundamentalists. Introduction. There has been a strong tendency in the philosophical literature to conflate determinism and causality, or at the very least, to see the former as a particularly strong form of the latter. The tendency persists even today. When the editors of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asked me to write the entry on determinism, I found that the title was to be “Causal determinism”.1 I therefore felt obliged to point out in the opening paragraph that determinism actually has little or nothing to do with causation; for the philosophical tradition has it all wrong. What I hope to show in this paper is that, in fact, in a complex world such as the one we inhabit, determinism and genuine causality are probably incompatible with each other. -

A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws Andrew Michael Winters University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-20-2015 A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws Andrew Michael Winters University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy of Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Winters, Andrew Michael, "A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5603 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Natural Case for Realism: Processes, Structures, and Laws by Andrew Michael Winters A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Douglas Jesseph, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Alexander Levine, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Otávio Bueno, Ph.D. John Carroll, Ph.D. Eric Winsberg, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 20th, 2015 Keywords: Metaphysics, Epistemology, Naturalism, Ontology Copyright © 2015, Andrew Michael Winters DEDICATION For Amie ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my co-chairs, Doug Jesseph and Alex Levine, for providing amazing support in all aspects of my tenure at USF. I greatly appreciate the numerous conversations with my committee members, Roger Ariew, Otávio Bueno, John Carroll, and Eric Winsberg, which resulted in a (hopefully) more refined and clearer dissertation. -

Action Verbs

ACTION VERBS Accepts To receive as true; to regard as proper, normal, inevitable Accounts To give a report on; to furnish a justifying analysis or explanation Accumulates To collect; to gather Achieves To bring to a successful conclusion Acknowledges To report the receipt of Acquires To come into possession of Activates To mobilize; to set into motion Acts To perform a specified function Adapts To suit or fit by modification Adjusts To bring to a more satisfactory state; to bring the parts of something to a true or more effective position Administers To manage or direct the execution of affairs Adopts To take up and practice as one's own Advises To recommend a course of action; to offer an informed opinion based on specialized knowledge Advocates To recommend or speak in favor of Affirms To assert positively; to confirm Aligns To arrange in a line; to array Allots To assign as a share Alters To make different without changing into something else Amends To change or modify for the better Analyzes To separate into elements and critically examine Answers To speak or write in reply Anticipates To foresee and deal with in advance Applies To put to use for a purpose; to employ diligently or with close attention Appoints To name officially Appraises To give an expert judgment of worth or merit Approves To accept as satisfactory; to exercise final authority with regard to commitment of resources Arranges To prepare for an event; to put in proper order Ascertains To find out or discover through examination; to find out or learn for a certainty -

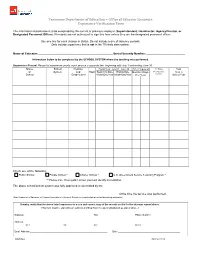

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting