Robbins Et Al.Fm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA)

Cotinga 33 The birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Leonardo Pimentel and Fábio Olmos Received 30 September 2009; final revision accepted 15 December 2010 Cotinga 33 (2011): OL 8–24 published online 16 March 2011 É apresentada uma lista da avifauna da Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu (REGUA), uma reserva privada de 6.500 ha localizada no município de Cachoeiras de Macacu, vizinha ao Parque Estadual dos Três Picos, Estação Ecológica do Paraíso e Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos, parte de um dos maiores conjuntos protegidos do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Foram registradas um total de 450 espécies de aves, das quais 63 consideradas de interesse para conservação, como Leucopternis lacernulatus, Harpyhaliaetus coronatus, Triclaria malachitacea, Myrmotherula minor, Dacnis nigripes, Sporophila frontalis e S. falcirostris. A reserva também está desenvolvendo um projeto de reintrodução dos localmente extintos Crax blumembachii e Aburria jacutinga, e de reforço das populações locais de Tinamus solitarius. The Atlantic Forest of eastern Brazil and Some information has been published on neighbouring Argentina and Paraguay is among the birds of lower (90–500 m) elevations in the the most imperilled biomes in the world. At region10,13, but few areas have been subject to least 188 bird species are endemic to it, and 70 long-term surveys. Here we present the cumulative globally threatened birds occur there, most of them list of a privately protected area, Reserva Ecológica endemics4,8. The Atlantic Forest is not homogeneous Guapiaçu (REGUA), which includes both low-lying and both latitudinal and longitudinal gradients parts of the Serra dos Órgãos massif and nearby account for diverse associations of discrete habitats higher ground, now mostly incorporated within and associated bird communities. -

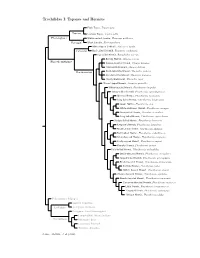

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Vogelliste Venezuela

Vogelliste Venezuela Datum: www.casa-vieja-merida.com (c) Beobachtungstage: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Birdlist VENEZUELA copyrightBeobachtungsgebiete: Henri Pittier Azulita / Catatumbo La Altamira St Domingo Paramo Los Llanos Caura Sierra de Imataca Sierra de Lema + Gran Sabana Sucre Berge und Kueste Transfers Andere - gesehen gesehen an wieviel Tagen TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae - Steißhühner 0 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius Gelbbrusttinamu 0 2 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei Bergtinamu 0 3 Gray Tinamou Tinamus tao Tao 0 4 Great Tinamou Tinamus major Großtinamu x 0 5 White-throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus Weißkehltinamu 0 6 Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus Grautinamu x x 0 7 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Brauntinamu x x x 0 8 Tepui Tinamou Crypturellus ptaritepui Tepuitinamu by 0 9 Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus Kastanientinamu 0 10 Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulatus Wellentinamu 0 11 Gray-legged Tinamou Crypturellus duidae Graufußtinamu 0 12 Red-legged Tinamou Crypturellus erythropus Rotfußtinamu birds-venezuela.dex x 0 13 Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus Rotbrusttinamu x x x 0 14 Barred Tinamou Crypturellus casiquiare Bindentinamu 0 ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae - Entenvögel 0 15 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta Hornwehrvogel x 0 16 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria Weißwangen-Wehrvogel x 0 17 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata Witwenpfeifgans x 0 18 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Rotschnabel-Pfeifgans x 0 19 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor -

Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation

THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PRODUCED IN GUIANAS COLLABORATION VERZICHT APERWITH: Ç 2016 Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 WWF-Guianas Global Wildlife Conservation Guyana Office PO Box 129 285 Irving Street, Queenstown Austin, TX 78767 USA Georgetown, Guyana [email protected] www.wwfguianas.org [email protected] Text: Juliana Persaud, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Concept: Francesca Masoero, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Design: Sita Sugrim for Kriti Review: Brian O’Shea, Deirdre Jaferally and Indranee Roopsind Map: Oronde Drakes Front cover photos (left to right): Rupununi Savannah © Zach Montes, Giant Ant Eater © Gerard Perreira, Red Siskin © Meshach Pierre, Jaguar © Evi Paemelaere. Inside cover photo: Gallery Forest © Andrew Snyder. OF BIODIVERSITYTHE SOUTHERN RUPUNUNI SAVANNAH. Guyana-South America. World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 This booklet has been produced and published thanks to: 1 WWF Biodiversity Assessment Team Expedition Southern Rupununi - Guyana. The Southern Rupununi Biodiversity Survey Team / © WWF - GWC. Biodiversity Assessment Team (BAT) Survey. This programme was created by WWF-Guianas in 2013 to contribute to sound land- use planning by filling biodiversity data gaps in critical areas in the Guianas. As far as possible, it also attempts to understand the local context of biodiversity use and the potential threats in order to recommend holistic conservation strategies. The programme brings together local knowledge experts and international scientists to assess priority areas. With each BAT Survey, species new to science or new country records are being discovered. This booklet acknowledges the findings of a BAT Survey carried out during October-November 2013 in the southern Rupununi savannah, at two locations: Kusad Mountain and Parabara. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

The Edgar Mittelholzer Memorial Lectures

BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Edited and with an Introduction by Andrew O. Lindsay 1 Edited by Andrew O. Lindsay BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES - VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Preface © Andrew Jefferson-Miles, 2014 Introduction © Andrew O. Lindsay, 2014 Cover design by Peepal Tree Press Cover photograph: Courtesy of Jacqueline Ward All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-67-6 2 Contents: Tenth Series, 1986: The Arawak Language in Guyanese Culture by John Peter Bennett FOREWORD by Denis Williams .......................................... 3 PREFACE ................................................................................. 5 THE NAMING OF COASTAL GUYANA .......................... 7 ARAWAK SUBSISTENCE AND GUYANESE CULTURE ........................................................................ 14 Eleventh Series, 1987. The Relevance of Myth by George P. Mentore PREFACE ............................................................................... 27 MYTHIC DISCOURSE......................................................... 29 SOCIETY IN SHODEWIKE ................................................ 35 THE SELF CONSTRUCTED ............................................... 43 REFERENCES ....................................................................... 51 Twelfth Series, 1997: Language and National Unity by Richard Allsopp CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD -

Additions to the Avifauna of Two Localities in the Southern Rupununi Region, Guyana 17

13 4 113–120 21 July 2017 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 13 (4): 113–120 https://doi.org/10.15560/13.4.113 Additions to the avifauna of two localities in the southern Rupununi region, Guyana Brian J. O’Shea,1, 2 Asaph Wilson,3 Jonathan K. Wrights4 1 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, 11 W. Jones Street, Raleigh, NC, 27601, USA, 2 Global Wildlife Conservation, PO Box 129, Austin TX 78767, USA. 3 South Rupununi Conservation Society, Shulinab, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo, Guyana. 4 National Agricultural Research and Extension Institute, National Plant Protection Organization, Mon Repos, East Coast Demerara, Guyana. Corresponding author: Brian J. O’Shea, [email protected] Abstract We report new records from ornithology surveys conducted at Kusad Mountain and Parabara savanna in Guyana’s southern Rupununi region during October and November 2013. Both localities had existing species lists based on surveys conducted in 2000, but had not been formally surveyed since. We surveyed birds over 15 field days, adding 22 and 10 species to the existing lists for Kusad and Parabara, respectively. Our findings augment prior knowledge of the status and distribution of birds in this region of the Guiana Shield. The southern Rupununi harbors high avian diversity, including rare species such as Rio Branco Antbird (Cercomacra carbonaria), Hoary-throated Spinetail (Synallaxis kollari), Bearded Tachuri (Polystictus pectoralis), and Red Siskin (Spinus cucullatus), which are likely to continue to draw tourism revenue to local communities if their habitats remain intact. Key words Neotropics; Guiana Shield; birds; inventory; conservation; savanna; ecotourism. Academic editor: Nárgila Gomes Moura | Received 9 December 2016 | Accepted 6 May 2017 | Published 21 July 2017 Citation: O’Shea BJ, Wilson A, Wrights JK (2017) Additions to the avifauna of two localities in the southern Rupununi region, Guyana. -

R Eference Year 2015

Monitoring the impact of gold mining on the forest cover and freshwater in the Guiana Shield August 2017 Reference year 2015 Authors: Rahm M.1, Thibault P.2, Shapiro A.2, Smartt T.3, Paloeng C. 4, Crabbe S.4, Farias P.5, Carvalho R. 5, Joubert P.6 Reviewers: Hausil F. 7, Rampersaud P. 7, Pinas J. 7, Oliveira M.8, Vallauri D.2 1ONF International (ONFI); 2World Wide Fund for Nature France (WWF France); 3Guyana Forestry Commission (GFC), 4Stichting voor Bosbeheer en Bostoezicht (SBB), 5Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente do Amapá (SEMA); 6Parc 7 8 Amazonien de Guyane (PAG), WWF Guianas, WWF Brasil Recommended citation: Rahm M., Thibault P., Shapiro A., Smartt T., Paloeng C., Crabbe S., Farias P., Carvalho R., Joubert P. (2017). Monitoring the impact of gold mining on the forest cover and freshwater in the Guiana Shield. Reference year 2015. pp.20 Acknowledgements: This project and its outcomes have been supported by the Guyana Forestry Commission (GFC) in Guyana, the Foundation for Forest Management and Production Control (SBB) in Suriname, the Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente do Amapá (SEMA) in Brazil, the Parc amazonien de Guyane in French Guiana and the WWF in Germany. We would like also to acknowledge the past technical cooperation project REDD+ for the Guiana Shield that helped to create a network of brilliant minds through intense training, the revealing of important data for the region and the production of a report which was fundamental for the present one. We would like to indicate the importance of this type of collaborative project to strengthen the dialog between countries and to share innovative methods to monitor the environmental impacts of human activities on the ecosystem. -

Exploring the Links Between Natural Resource Use and Biophysical Status in the Waterways of the North Rupununi, Guyana

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Exploring the links between natural resource use and biophysical status in the waterways of the North Rupununi, Guyana Journal Item How to cite: Mistry, Jayalaxshmi; Simpson, Matthews; Berardi, Andrea and Sandy, Yung (2004). Exploring the links between natural resource use and biophysical status in the waterways of the North Rupununi, Guyana. Journal of Environmental Management, 72(3) pp. 117–131. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2004 Elsevier Ltd. Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.03.010 http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/622871/description#description Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Journal of Environmental Management , 72 : 117-131. Exploring the links between natural resource use and biophysical status in the waterways of the North Rupununi, Guyana Dr. Jayalaxshmi Mistry1*, Dr Matthew Simpson2, Dr Andrea Berardi3, and Mr Yung Sandy4 1Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, UK. Telephone: +44 (0)1784 443652. Fax: +44 (0)1784 472836. E-mail: [email protected] 2Research Department, The Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Glos. GL2 7BT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 3Systems Discipline, Centre for Complexity and Change, Faculty of Technology, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK. -

Guyana: 3-Part Birding Adventure

GUYANA: 3-PART BIRDING ADVENTURE 25 JANUARY – 9 FEBRUARY 2020 Guianan Cock-of-the-rock is one of the key species we search for on this trip www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Guyana: 3-part Birding Adventure 2020 Our tour to South America’s “Biggest Little Secret” with its magnificent northern Amazon rainforest and numerous emerging birding hotspots offers an exploration of its unbelievably colorful and exciting birdlife, from the majestic Harpy Eagle to the stunning Guianan Cock-of- the-rock and, on a five-day post-extension, an opportunity to find Sun Parakeet and Red Siskin, both endangered, extremely range-restricted, and highly sought-after. The world’s highest uninterrupted waterfall, Kaieteur Falls, can also be visited and admired on a two-day pre- tour extension. This tour can be combined with our Trinidad and Tobago Birding Adventure 2020 tour. Pre-tour to Kaieteur Falls Itinerary (2 days/1 night) Day 1. Arrival We will pick you up at the airport in Georgetown and transfer you to your hotel. Overnight: Cara Lodge, Georgetown Cara Lodge was built in the 1840s and originally consisted of two houses. It has a long and romantic history and was the home of the first Lord Mayor of Georgetown. Over the years the property has been visited by many dignitaries, including King Edward VII, who stayed at the house in 1923. Other dignitaries have included President Jimmy Carter, HRH Prince Charles, HRH Prince Andrew, and Mick Jagger. This magnificent home turned hotel offers the tradition and nostalgia of a bygone era, complete with service and comfort in a congenial family atmosphere. -

Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation

THIS REPORT HAS BEEN GLOBAL PRODUCED IN WILDLIFE GUIANAS COLLABORATION CONSERVATION VERZICHT APERWITH: Ç 2016 Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 WWF-Guianas Global Wildlife Conservation Guyana Office PO Box 129 285 Irving Street, Queenstown Austin, TX 78767 USA Georgetown, Guyana [email protected] www.wwfguianas.org [email protected] Text: Juliana Persaud, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Concept: Francesca Masoero, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Design: Sita Sugrim for Kriti Review: Brian O’Shea, Deirdre Jaferally and Indranee Roopsind Map: Oronde Drakes Front cover photos (left to right): Rupununi Savannah © Zach Montes, Giant Ant Eater © Gerard Perreira, Red Siskin © Meshach Pierre, Jaguar © Evi Paemelaere. Inside cover photo: Gallery Forest © Andrew Snyder. OF BIODIVERSITYTHE SOUTHERN RUPUNUNI SAVANNAH. Guyana-South America. World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 This booklet has been produced and published thanks to: 1 WWF Biodiversity Assessment Team Expedition Southern Rupununi - Guyana. The Southern Rupununi Biodiversity Survey Team / © WWF - GWC. Biodiversity Assessment Team (BAT) Survey. This programme was created by WWF-Guianas in 2013 to contribute to sound land- use planning by filling biodiversity data gaps in critical areas in the Guianas. As far as possible, it also attempts to understand the local context of biodiversity use and the potential threats in order to recommend holistic conservation strategies. The programme brings together local knowledge experts and international scientists to assess priority areas. With each BAT Survey, species new to science or new country records are being discovered. This booklet acknowledges the findings of a BAT Survey carried out during October-November 2013 in the southern Rupununi savannah, at two locations: Kusad Mountain and Parabara. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í.