Latin American Music Notes© William Little (2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Folk Music in the Melting Pot” at the Sheldon Concert Hall

Education Program Handbook for Teachers WELCOME We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Sheldon Concert Hall for one of our Education Programs. We hope that the perfect acoustics and intimacy of the hall will make this an important and memorable experience. ARRIVAL AND PARKING We urge you to arrive at The Sheldon Concert Hall 15 to 30 minutes prior to the program. This will allow you to be seated in time for the performance and will allow a little extra time in case you encounter traffic on the way. Seating will be on a first come-first serve basis as schools arrive. To accommodate school schedules, we will start on time. The Sheldon is located at 3648 Washington Boulevard, just around the corner from the Fox Theatre. Parking is free for school buses and cars and will be available on Washington near The Sheldon. Please enter by the steps leading up to the concert hall front door. If you have a disabled student, please call The Sheldon (314-533-9900) to make arrangement to use our street level entrance and elevator to the concert hall. CONCERT MANNERS Please coach your students on good concert manners before coming to The Sheldon Concert Hall. Good audiences love to listen to music and they love to show their appreciation with applause, usually at the end of an entire piece and occasionally after a good solo by one of the musicians. Urge your students to take in and enjoy the great music being performed. Food and drink are prohibited in The Sheldon Concert Hall. -

Excitement Building for Bristol's Old Home Day Celebration

Bears looking at some rebuilding Story on Page B1 THURSDAY,Newfound AUGUST 27, 2015 FREE IN PRINT, FREE ON-LINE • WWW.NEWFOUNDLANDING.COM Landing COMPLIMENTARY Excitement building for Bristol’s Old Home Day celebration BY DONNA RHODES [email protected] ty and address the state’s BRISTOL — It’s time latest drug epidemic. once again to gather the Registration will take family and join your place beside the tennis friends and neighbors courts at 7:30 a.m., and for the annual Bristol the first 35 entrants will Old Home Day, which receive a free tee shirt. will be held on Saturday, The race then hits the Aug. 29, at Kelley Park, road at 8 a.m. off North Main Street in Also from 8 until downtown Bristol. 11 a.m., there will be a Leslie Dion, one of buffet breakfast served many who have worked at the Union Lodge on hard to make this year’s Pleasant Street for those celebration another big who want to start the success, said it will be day off with a great meal. the perfect time to bring At 9 a.m., the public is the kids to the park for asked to come cheer on some summertime fun an adult softball league’s before the new school championship game and year begins. everyone is also invited “This year, we have to join in the horseshoe a great line-up of kids tournament behind the games, like Water Wars, Middle School at 10 a.m., an inflatable obsta- which will offer cash cle course, and a ‘hose prizes for winners. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

©Studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I Thank You For

©studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I thank you for StudentSavvy © 2016 downloading! Thank you for downloading StudentSavvy’s Music Around the World Unit! If you have any questions regarding this product, please email me at [email protected] Be sure to stay updated and follow for the latest freebies and giveaways! studentsavvyontpt.blogspot.com www.facebook.com/studentsavvy www.pinterest.com/studentsavvy wwww.teacherspayteachers.com/store/studentsavvy clipart by EduClips and IROM BOOK http://www.hm.h555.net/~irom/musical_instruments/ Don’t have a QR Code Reader? That’s okay! Here are the URL links to all the video clips in the unit! Music of Spain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7C8MdtnIHg Music of Japan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OA8HFUNfIk Music of Africa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g19eRur0v0 Music of Italy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3FOjDnNPHw Music of India: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQ2Yr14Y2e0 Music of Russia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEiujug_Zcs Music of France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ge46oJju-JE Music of Brazil: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQLvGghaDbE ©StudentSavvy2016 Don’t leave out these countries in your music study! Click here to study the music of Mexico, China, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, USA, Hawaii, and the U.K. You may also enjoy these related resources: Music Around the WorLd Table Of Contents Overview of Musical Instrument Categories…………………6 Music of Japan – Read and Learn……………………………………7 Music of Japan – What I learned – Recall.……………………..8 Explore -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

2015 Review from the Director

2015 REVIEW From the Director I am often asked, “Where is the Center going?” Looking of our Smithsonian Capital Campaign goal of $4 million, forward to 2016, I am happy to share in the following and we plan to build on our cultural sustainability and pages several accomplishments from the past year that fundraising efforts in 2016. illustrate where we’re headed next. This year we invested in strengthening our research and At the top of my list of priorities for 2016 is strengthening outreach by publishing an astonishing 56 pieces, growing our two signatures programs, the Smithsonian Folklife our reputation for serious scholarship and expanding Festival and Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. For the our audience. We plan to expand on this work by hiring Festival, we are transitioning to a new funding model a curator with expertise in digital and emerging media and reorganizing to ensure the event enters its fiftieth and Latino culture in 2016. We also improved care for our anniversary year on a solid foundation. We embarked on collections by hiring two new staff archivists and stabilizing a search for a new director and curator of Smithsonian access to funds for our Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Folkways as Daniel Sheehy prepares for retirement, Collections. We are investing in deeper public engagement and we look forward to welcoming a new leader to the by embarking on a strategic communications planning Smithsonian’s nonprofit record label this year. While 2015 project, staffing communications work, and expanding our was a year of transition for both programs, I am confident digital offerings. -

Musical Explorers Is Made Available to a Nationwide Audience Through Carnegie Hall’S Weill Music Institute

Weill Music Institute Teacher Musical Guide Explorers My City, My Song A Program of the Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall for Students in Grades K–2 2016 | 2017 Weill Music Institute Teacher Musical Guide Explorers My City, My Song A Program of the Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall for Students in Grades K–2 2016 | 2017 WEILL MUSIC INSTITUTE Joanna Massey, Director, School Programs Amy Mereson, Assistant Director, Elementary School Programs Rigdzin Pema Collins, Coordinator, Elementary School Programs Tom Werring, Administrative Assistant, School Programs ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTERS Michael Daves Qian Yi Alsarah Nahid Abunama-Elgadi Etienne Charles Teni Apelian Yeraz Markarian Anaïs Tekerian Reph Starr Patty Dukes Shanna Lesniak Savannah Music Festival PUBLISHING AND CREATIVE SERVICES Carol Ann Cheung, Senior Editor Eric Lubarsky, Senior Editor Raphael Davison, Senior Graphic Designer ILLUSTRATIONS Sophie Hogarth AUDIO PRODUCTION Jeff Cook Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall 881 Seventh Avenue | New York, NY 10019 Phone: 212-903-9670 | Fax: 212-903-0758 [email protected] carnegiehall.org/MusicalExplorers Musical Explorers is made available to a nationwide audience through Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute. Lead funding for Musical Explorers has been provided by Ralph W. and Leona Kern. Major funding for Musical Explorers has been provided by the E.H.A. Foundation and The Walt Disney Company. © Additional support has been provided by the Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation, The Lanie & Ethel Foundation, and -

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by K. Meira Goldberg, Antoni Pizà and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9963-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9963-5 Proceedings from the international conference organized and held at THE FOUNDATION FOR IBERIAN MUSIC, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, on April 17 and 18, 2015 This volume is a revised and translated edition of bilingual conference proceedings published by the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía, Música Oral del Sur, vol. 12 (2015). The bilingual proceedings may be accessed here: http://www.centrodedocumentacionmusicaldeandalucia.es/opencms/do cumentacion/revistas/revistas-mos/musica-oral-del-sur-n12.html Frontispiece images: David Durán Barrera, of the group Los Jilguerillos del Huerto, Huetamo, (Michoacán), June 11, 2011. -

Program Notes

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

Standing up to Peer Pressure, One Song at a Time

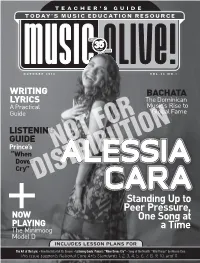

TEACHER’S GUIDE OCTOBER 2016 VOL.36 NO.1 WRITING BACHATA LYRICS The Dominican A Practical Music’s Rise to Guide Global Fame LISTENING GUIDE Prince’s NOT FOR “When Doves ALESSIA Cry” DISTRIBUTIONCARA Standing Up to Peer Pressure, NOW One Song at PLAYING a Time The Minimoog Model D INCLUDES LESSON PLANS FOR The Art of the Lyric • How Bachata Got Its Groove • Listening Guide: Prince’s “When Doves Cry” • Song of the Month: “Wild Things” by Alessia Cara This issue supports National Core Arts Standards 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the 36th season of Music Alive! Beginning with this season, I’ll be following in the foot- October 2016 steps of my esteemed colleague Mac Randall as the new ed- Vol. 36 • No. 1 itor-in-chief of Music Alive! Magazine. As a writer, musician, and part-time music teacher, I’m excited to be in a position CONTENTS of selecting and editing content to be shared with young music students through Music Alive! Music’s value as an educational subject 3 The Art of the Lyric is frequently reported on by the media, but for those of us who are passionate about music education, its importance is common knowledge. Whether or not 4 How Bachata students intend to become professional musicians, we know that their studies Got Its Groove in music will be invaluable to them. As we move forward with Volume 36, we hope to provide you and your 5 Listening Guide: students with content that will not only inspire them but will also challenge Prince’s “When them—whether it’s in understanding a technical aspect of music, wrapping Doves Cry” their minds around the inner workings of the music industry, or opening their ears toNOT the sounds of different FOR cultures and subcultures. -

E V a N G E L I

presents E EVANGELINE, V THE QUEEN OF MAKE-BELIEVE A 1968. East L.A. explodes in a civil rights movement as Evangeline, a devoted N daughter by day and go-go dancer by night, embarks on a journey of self-discovery. “A living history, combining a piquant upbeat G musical score with salient–People’s resonance World to current E day issues.” L I Created by Theresa CHAVEZ, N Nina Diaz, “The Neighborhood” Louie PÉREZ and bandband LeadLead SingerSinger E Rose PORTILL0 Music by David HIDALGO & Louie PÉREZ of Los Lobos Heralded by Latino Weekly as a “beautifully crafted multimedia experience,” this PLAY with MUSIC returns to Lincoln Height’s Plaza de la Raza. With its reimagined “Los Lobos songbook as a reverb-drenched 60’s garage band,” NINA DIAZ (Girl in a Coma) fronts “The Neighborhood” band. April 4-14, 2019 Plaza de la Raza 3540 N. Mission Road, Los Angeles, CA 90031 Follow us on: @AboutPD presents E V A N EVANGELINE, G E THE QUEEN OF L I N MAKE-BELIEVE E story BY Theresa CHAVEZ, Louie PÉREZ and Rose PORTILLO written BY Theresa CHAVEZ and Rose PORTILLO directed BY Theresa CHAVEZ FEATURING THE MUSIC OF David HIDALGO & Louie PÉREZ cast Elizabeth ALVAREZ……....................…………..................................………………...Alicia Adrian BRIZUELA……………...................…................................…………Edgar/James Sarah CORTEZ*…………........................................................………………...Evangeline Moises CASTRO*……………................................................................………………...Ray Ariana GONZALEZ……................................................................…………...Ensemble