Sf Commentary 86

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Report #1

Welcome to the first progress report for the 2021 World Fantasy Convention! We are pressing on, in times of Covid, and continuing to plan a wonderful in person convention in Montréal, Canada. We have a stunning guest list and a superlative team for both planning and the creation of the gathering not to be missed. We will be at the Hôtel Bonaventure, an iconic landmark in the city. The hotel is located in the heart of downtown and just outside the Old Port of Montréal. It is near major roads, right across the street from Gare Centrale, the Montréal train station, and is directly connected to two Metro stations, making it easily accessible for both motorists and public transport users. We will be able to enjoy a lavish 2.5 acres of gardens with streams inhabited by ducks and fish as well as a year-round outdoor heated pool. Our committee is busy excitedly planning a convention that will surpass your every expectation. Our theme will be YA fantasy. The field of young adult fantasy has grown from being popular to becoming a dominant category of 21st century literature, bringing millions of new readers to hundreds of new authors. We are working on a diverse program that will explore this genre that celebrates fantasy fiction in all of its forms: epic, dark, paranormal, urban, and other varieties. We invite members to share what they enjoy, what they have learned, what they have written themselves, and what they hope to see coming in the field of young adult fantasy fiction. We look forward to seeing you all in Montréal! Diane Lacey Chair Diversity Statement The committee for the 2021 World Fantasy Convention is unconditionally devoted to promoting diversity within our convention. -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT.......... -

Steam Engine Time 7

Steam Engine Time Everything you wanted to know about SHORT STORIES ALAN GARNER HOWARD WALDROP BOOK AWARDS HARRY POTTER Matthew Davis Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie David J. Lake Robert Mapson Gillian Polack David L. Russell Ray Wood and many others Issue 7 October 2007 Steam Engine Time 7 If human thought is a growth, like all other growths, its logic is without foundation of its own, and is only the adjusting constructiveness of all other growing things. A tree cannot find out, as it were, how to blossom, until comes blossom-time. A social growth cannot find out the use of steam engines, until comes steam-engine time. — Charles Fort, Lo!, quoted in Westfahl, Science Fiction Quotations, Yale UP, 2005, p. 286 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 7, October 2007 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from http://efanzines.com, or enquire from either of our email addresses. In future, the print edition will only be available by negotiation with the editors (see pp. 6–8). All other readers should (a) tell the editors that they wish to become Downloaders, i.e. be notified by email when each issue appears; and (b) download each issue in .PDF format from efanzines.com. Printed by Copy Place, Basement, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. Illustrations Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover); David Russell (p. 3). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos by Cath Ortlieb (p. -

New Cultural Models in Women-S Fantasy Literature Sarah Jane Gamble Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University

NEW CULTURAL MODELS IN WOMEN-S FANTASY LITERATURE SARAH JANE GAMBLE SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD, DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE OCTOBER 1991 NEW CULTURAL MODELS IN WOMEN'S FANTASY LITERATURE Sarah Jane Gamble This thesis examines the way in which modern women writers use non realistic literary forms in order to create new role models of and for women. The work of six authors are analysed in detail - Angela Carter, Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, Ursula Le Guin, Joanna Russ and Kate Wilhelm. I argue that they share a discontent with the conventions of classic realism, which they all regard as perpetuating ideologically-generated stereotypes of women. Accordingly, they move away from mimetic modes in order to formulate a discourse which will challenge conventional representations of the 'feminine', arriving at a new conception of the female subject. I argue that although these writers represent a range of feminist responses to the dominant order, they all arrive at a s1mil~r conviction that such an order is male-dominated. All exhibit an awareness of the work of feminist critics, creating texts which consciously interact with feminist theory. I then discuss how these authors use their art to examine the their own situation as women who write. All draw the attention to the existence of a tradition of female censorship, whereby the creative woman has experienced, in an intensified form, the repreSSion experienced by all women in a culture which privileges the male over the female. All these writers exhibit a desire to escape such a tradition, progressing towards the formulation of a utopian female subject who is free to be fully creative a project they represent metaphorically in the form of a quest. -

A Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association in This Issue

294 Fall 2010 Editors Karen Hellekson SFRA 16 Rolling Rdg. A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Jay, ME 04239 Review [email protected] [email protected] Craig Jacobsen English Department Mesa Community College 1833 West Southern Ave. Mesa, AZ 85202 [email protected] In This Issue [email protected] SFRA Review Business Managing Editor Out With the Old, In With the New 2 Janice M. Bogstad SFRA Business McIntyre Library-CD University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Thanks and Congratulations 2 105 Garfield Ave. 101s and Features Now Available on Website 3 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 SFRA Election Results 4 [email protected] SFRA 2011: Poland 4 Nonfiction Editor Features Ed McKnight Feminist SF 101 4 113 Cannon Lane Research Trip to Georgia Tech’s SF Collection 8 Taylors, SC 29687 [email protected] Nonfiction Reviews The Business of $cience Fiction 9 Fiction Editor Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick 9 Edward Carmien Fiction Reviews 29 Sterling Rd. Directive 51 10 Princeton, NJ 08540 Omnitopia Dawn 11 [email protected] The Passage: A Novel 12 Media Editor Dust 14 Ritch Calvin Gateways 14 16A Erland Rd. The Stainless Steel Rat Returns 15 Stony Brook, NY 11790-1114 [email protected] Media Reviews The SFRA Review (ISSN 1068- I’m Here 16 395X) is published four times a year by Alice 17 the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA), and distributed to SFRA members. Splice 18 Individual issues are not for sale; however, Star Trek: The Key Collection 19 all issues after 256 are published to SFRA’s Website (http://www.sfra.org/) no fewer than The Trial 20 10 weeks after paper publication. -

Programming Participants' Guide and Biographies

Programming Participants’ Guide and Biographies Compliments of the Conference Cassette Company The official audio recorders of Chicon 2000 Audio cassettes available for sale on site and post convention. Conference Cassette Company George Williams Phone: (410) 643-4190 310 Love Point Road, Suite 101 Stevensville MD 21666 Chicon. 2000 Programming Participant's Guide Table of Contents A Letter from the Chairman Programming Director's Welcome................................................... 1 By Tom Veal A Letter from the Chairman.............................................................1 Before the Internet, there was television. Before The Importance of Programming to a Convention........................... 2 television, there were movies. Before movies, there Workicon Programming - Then and Now........................................3 were printed books. Before printed books, there were The Minicon Moderator Tip Sheet................................................... 5 manuscripts. Before manuscripts, there were tablets. A Neo-Pro's Guide to Fandom and Con-dom.................................. 9 Before tablets, there was talking. Each technique Chicon Programming Managers..................................................... 15 improved on its successor. Yet now, six thousand years Program Participants' Biographies................................................... 16 after this progression began, we humans do most of our teaching and learning through the earliest method: unadorned, unmediated speech. Programming Director’s Welcome -

Progress Report One Guests of Honor Guy Gavriel Kay Les Edwards Stuart David Schiff Special Guest Lail Finlay Toastmaster Jane Yolen

World Fantasy Convention 2014 November 6 - November 9, 2014 Washington, D.C. Progress Report One Guests of Honor Guy Gavriel Kay Les Edwards Stuart David Schiff Special Guest Lail Finlay Toastmaster Jane Yolen Contact Information 2014 World Fantasy Convention Post Office Box 314 Annapolis Junction, MD 20701-0314 www. worldfantasy2014.org • [email protected] www.facebook.com/WorldFantasy40 1 1914 ~ 2014 • Three Centennials The Year Nineteen-fourteen was a time of great transition, and the 40th World Fan- tasy Convention will focus on this with our commemoration of the births of the artist Virgil Finlay and the author Robert Aickman, as well as the beginning of World War I. We welcome you to join us in exploring the many facets, both light and dark, of these forces that shaped the future. Robert Aickman Robert Fordyce Aickman (1914-1981) was a distinguished British author of stories of the supernatural. He published a number of books including The Late Breakfasters, Cold Hand in Mine, Intrusions, and an acclaimed autobiography entitled The Attempted Rescue. The grandson of the noted Victorian novelist Richard Marsh, Aickman won the World Fantasy Award in 1975. Virgil Finlay Virgil Warden Finlay (1914-1971) was a science fiction and horror illus- trator. He became famous for his beautifully detailed pen-and-ink and scratchboard techniques. He created more than 2600 drawings using everything from pen-and-ink to scratchboard to gouache to oils. He was known especially for his cross-hatching and abundant stippling, which were very labor-intensive and time-consuming. During World War II he saw extensive combat in the South Pacific theatre. -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

H.P. Lovecraft and the Creation of Horror

H.P. Lovecraft and the Creation of Horror University of Tampere Department of English Pro Gradu Thesis Spring 2002 Saijamari Männikkö Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia MÄNNIKKÖ, SAIJAMARI: H.P. Lovecraft and the Creation of Horror Pro gradu –tutkielma, 74 s. Kevät 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ Tämän työn tarkoituksena on tarkastella sitä, kuinka kauhu syntyy H.P. Lovecraftin pienoisromaanissa The Shadow over Innsmouth (1936, suom. Varjo Innsmouthin yllä 1989). Lovecraftin kauhutarinoissa tiivistyy hänen kosminen maailmankuvansa, jonka mittakaavassa ihmisellä ja hänen suuruudenkuvitelmillaan ei ole mitään merkitystä. Lovecraft-kriitikko Donald R. Burlesonin käsityksen mukaan Lovecraftin lähestymistapa fiktioon on ”ironisen impressionistinen.” Käsite viittaa ihmisen kykyyn havaita oma merkityksettömyytensä juuri niiden aistien kautta, joiden vuoksi ihminen pitää itseään erikoislaatuisena olentona. Yksi kauhuelementti Lovecraftin tarinoissa onkin se, kuinka päähenkilön kauhukokemus paljastaa tälle ihmisen merkityksettömyyden kosmisessa ajan ja paikan mittakaavassa. Kauhukokemuksen synnyttämä tunnereaktio on tarinoissa tärkeämpi kuin sen aiheuttaneet ihmiskuntaa muinaisemmat hirviöt, koska lukija voi tuntea kertojan kauhun ja epävarmuuden olemassaolonsa perusteista uskomatta itse hirviöihin. Lovecraftin filosofiaan perehtyneelle Timo Airaksiselle hirviöt ovat juuri vain luomuksia, joihin lukija tukeutuu selittääkseen itselleen kauhun tunteensa. Kauhu syntyy tuntemattomien kauhujen maailman -

Sample File VOL

Sample file VOL. 66, NO. 4 • ISSUE 360 Table of Contents Weird Tales was the The Eyrie 3 first storytelling magazine The Den 5 devoted explicitly to the Lost in Lovecraft 87 realm of the dark and fantastic. THE ELDER GODS The Long Last Night by Brian Lumley 8 Founded in 1923, Weird Momma Durtt by Michael Shea 25 Tales provided a literary The Darkness at Table Rock Road by Michael Reyes 36 home for such diverse The Runners Beyond the Wall by Darrell Schweitzer 45 wielders of the imagination Drain by Matthew Jackson 55 as H. P. Lovecraft (creator The Thing in the Cellar by William Blake-Smith 63 of Cthulhu), Robert E. Howard (creator of FoundSample in a Bus Shelter file at 3:00 AM, Conan the Barbarian), Under a Mostly Empty Sky by Stephen Gracia 67 Margaret Brundage (artistic godmother of goth UNTHEMED FICTION fetishism), and Ray Bradbury To Be a Star by Parke Godwin 69 (author of The Illustrated The Empty City by Jessica Amanda Salmonson 75 Man and Something Wicked Abbey at the Edge of the Earth by Collin B. Greenwood 83 This Way Comes). Alien Abduction by M. E. Brines 85 Today, O wondrous reader POETRY of the 21st century, we Mummified by Jill Bauman 7 continue to seek out that In Shadowy Innsmouth by Darrell Schweitzer 24 which is most weird and The Country of Fear by Russell Brickey 54 unsettling, for your own Country Midnight by Carole Buggé 62 edification and alarm. by Danielle Tunstall ALL writers Cover Photo OF sucH stORIES ARE PROPHETS SUBSCRIBE AT WWW.WEIRDTALESMAGAZINE.COM 1 VOL. -

World Fantasy Convention Progress Report #2

Address Correction Requested Address CorrectionRequested Convention 2004 2004 Convention World Fantasy Tempe, AZ 85285-6665Tempe, USA C/O LepreconInc. P.O. Box26665 The 30th Annual World Fantasy Convention October 28-31, 2004 Tempe Mission Palms Hotel Tempe, Arizona USA Progress Report #2 P 12 P 1 Leprecon Inc. presents World Fantasy Con 2004 Registration Form NAME(S) _____________________________________________________________ The 30th Annual ADDRESS ____________________________________________________________ World Fantasy Convention CITY _________________________________________________________________ October 28-31, 2004 STATE/PROVINCE _____________________________________________________ Tempe Mission Palms Hotel ZIP/POSTAL CODE _____________________________________________________ Tempe, Arizona USA COUNTRY ____________________________________________________________ EMAIL _______________________________________________________________ Author Guest of Honour PHONE _______________________________________________________________ Gwyneth Jones FAX __________________________________________________________________ Artist Guest of Honor PROFESSION (Writer, Artist, Editor, Fan, etc.) ______________________________________________________________________ Janny Wurts _______ Supporting Membership(s) at US$35 each = US$_________ Editor Guest of Honor _______ Attending Membership(s) at US$_______ each = US$_________ Ellen Datlow _______ Banquet Tickets at US$53 each = US$ _________ Total US$___________ Publisher Guest of Honor _______ Check: -

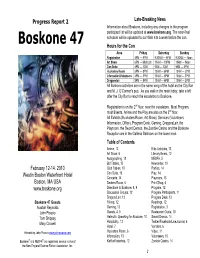

Boskone Guests Registration Will Be Open Friday (Starting 4PM) Through Sunday (Noon) in the Second Floor Pre-Function Area

Progress Report 2 Late-Breaking News Information about Boskone, including any changes to the program participant list will be updated at www.boskone.org. The near-final schedule will be uploaded to our Web site a week before the con. Boskone 47 Hours for the Con Area Friday Saturday Sunday Registration 4PM — 9PM 9:30AM — 6PM 9:30AM — Noon Art Show 6PM — Midnight 10AM — 10PM 10AM — Noon Con Suite 4PM — 1AM 9AM — 1AM 9AM — 4PM Hucksters Room 5PM — 8PM 10AM — 6PM 10AM — 3PM Information/Volunteers 4PM — 9PM 10AM — 6PM 10AM — 3PM Dragonslair 5PM — 8PM 10AM — 6PM 10AM — 3PM All Boskone activities are in the same wing of the hotel as the City Bar and M. J. O’Connor’s pub. As you walk in the main lobby, take a left after the City Bar to reach the escalators to Boskone. Registration is on the 2nd floor, near the escalators. Most Program, most Events, Anime and the Play are also on the 2nd floor. All Exhibits (Hucksters Room, Art Show), Services (Volunteers, Information, Office), Program Desk, Gaming, DragonsLair, the Playroom, the Sword Demos, the Zombie Casino and the Boskone Reception are in the Galleria Ballroom on the lower level. Table of Contents Anime, 12 Kids Activities, 13 Art Show, 6 Literary Beers, 12 Autographing, 12 NESFA, 5 Bid Tables, 10 Newsletter, 10 February 12-14. 2010 Club Tables, 10 Parties, 14 Con Suite, 13 Play, 14 Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel Concerts, 14 Playroom, 13 Boston, MA USA Dealers Room, 6 Print Shop, 6 www.boskone.org Directions to Boskone, 8, 9 Program, 12 Discussion Groups, 12 Program Participants, 11 DragonsLair,