(Sub-Committee F) EU INTERNA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

Spooks Returns to Dvd

A BAPTISM OF FIRE FOR THE NEW TEAM AS SPOOKS RETURNS TO DVD SPOOKS: SERIES NINE AVALIABLE ON DVD FROM 28TH FEBRUARY 2011 “Who doesn’t feel a thrill of excitement when a new series of Spooks hits our screens?” Daily Mail “It’s a tribute to Spooks’ staying power that after eight years we still care so much” The Telegraph BAFTA Award‐winning British television spy drama Spooks is back for its ninth knuckle‐clenching series and is available on DVD from 28th February 2011 courtesy of Universal Playback. Filled with spy‐tastic extra features, the DVD is a must for any die‐hard Spooks fan. The ninth series of the critically acclaimed Spooks, is filled with dramatic revelations and a host of new characters ‐ Sophia Myles (Underworld, Doctor Who), Max Brown (Mistresses, The Tudors), Iain Glen (The Blue Room, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), Simon Russell Beale (Much Ado About Nothing, Uncle Vanya) and Laila Rouass (Primeval, Footballers’ Wives). Friendships will be tested and the depth of deceit will lead to an unprecedented game of cat and mouse and the impact this has on the team dynamic will have viewers enthralled. Follow the team on a whirlwind adventure tracking Somalian terrorists, preventing assassination attempts, avoiding bomb efforts and vicious snipers, and through it all face the personal consequences of working for the MI5. The complete Spooks: Series 9 DVD boxset contains never before seen extras such as a feature on The Cost of Being a Spy and a look at The Downfall of Lucas North. Episode commentaries with the cast and crew will also reveal secrets that have so far remained strictly confidential. -

ANCIENT SPOOKS Part III: Link to a Spooky Past

ANCIENT SPOOKS Part III: Link to a spooky past By Gerry, July 2018 Click here to read Eustace Mullins - The Curse Of Satanic Canaan; A Satanic Demonology Of History (1987) http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-I-Pun-Factor-Spookery- Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The-War-Against-Shem- Transgression-of-Cain-Secular-Humanism.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-II-Spookish-relations- Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-England-French-Revolution- American-Revolution.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-III-Miles-Mathis-Link-to-a- spooky-past-Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The-American- Civil-War-State-of-Virginia-World-Wars.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-IV-Miles-Mathis- Spookdom-history-Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The- Menace-of-Communism-The-Promise.pdf Hello again, dear readers. I welcome you all to our central piece, where I am going to share my link to the Ancient Spookians, the progenitors of today’s hidden aristocracy. If you came here by coincidence and don’t know what I’m talking about, I’d suggest you read the other papers first. This one will be very uncomfortable since it concerns the Names of God. Yes, that God. I think some of God’s names were edited away, because either someone played around with those names, or the Biblical editors thought someone did, or the Biblical editors thought that some Biblical readers would think someone did. I am one of those readers. We’ll also see that the editors weren’t paranoid: A lot of Biblical material refers to Ancient Spookia, and a lot of puns as well. -

Richard Armitage

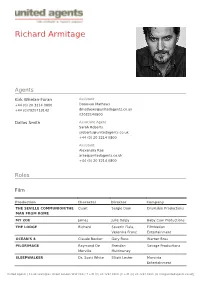

Richard Armitage Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE SEVILLE COMMUNION/THE Quart Sergio Dow Drumskin Productions MAN FROM ROME MY ZOE James Julie Delpy Baby Cow Productions THE LODGE Richard Severin Fiala, FilmNation Veronika Franz Entertainment OCEAN'S 8 Claude Becker Gary Ross Warner Bros PILGRIMAGE Raymond De Brendan Savage Productions Merville Muldowney SLEEPWALKER Dr. Scott White Elliott Lester Marvista Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company BRAIN ON FIRE Tom Cahalan Gerard Barrett Broad Green Pictures ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING King Oleron James Bobin Walt Disney Pictures GLASS URBAN AND THE SHED CREW Chop Candida Brady Blenheim Films THE HOBBIT: THE BATTLE OF Thorin Peter Jackson MGM THE FIVE ARMIES Oakenshield INTO THE STORM Gary Morris Steven Quale Broken Road/New Line THE HOBBIT - THE DESOLATION Thorin Peter Jackson MGM OF SMAUG Oakenshield THE HOBBIT - AN UNEXPECTED Thorin Peter Jackson MGM JOURNEY Oakenshield CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST Heinz Kruger Joe Johnston Marvel AVENGER CLEOPATRA Epiphanes Frank Roddan Alexandria Films FROZEN Steven Juliet McKoen Liminal Films MACBETH Angus -

GCHQ): New Accommodation Programme

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ): New Accommodation Programme Twenty–third Report of Session 2003–04 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 May 2004 HC 65 Published on 15 June 2004 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £10.00 The Committee of Public Accounts The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No 148). Current membership Mr Edward Leigh MP (Conservative, Gainsborough) (Chairman) Mr Richard Allan MP (Liberal Democrat, Sheffield Hallam) Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) Mrs Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton and Honiton) Jon Cruddas MP (Labour, Dagenham) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton and Ripon) Mr Ian Davidson MP (Labour, Glasgow Pollock) Rt Hon Frank Field MP (Labour, Birkenhead) Mr Brian Jenkins MP (Labour, Tamworth) Mr Nigel Jones MP (Liberal Democrat, Cheltenham) Ms Ruth Kelly MP (Labour, Bolton West) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, West Renfrewshire) Mr Siôn Simon MP (Labour, Birmingham Erdington) Mr Gerry Steinberg MP (Labour, City of Durham) Jon Trickett MP (Labour, Hemsworth) Rt Hon Alan Williams MP (Labour, Swansea West) The following was also a member of the Committee during the period of this inquiry. Mr Nick Gibb MP (Conservative, Bognor Regis and Littlehampton) Mr George Osborne MP (Conservative, Tatton) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 148. -

Aiza Khan Professor Reza Pirbhai ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Georgetown University Beyond Activity and Passivity The Oral Life History of an Afghan Refugee Woman in Pakistan Aiza Khan Professor Reza Pirbhai ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing a thesis is harder than I expected and more rewarding than I could have imagined. I would like to acknowledge all the people whose assistance was a milestone in the completion of this project. I have to start by thanking my mentor, Professor Reza Pirbhai, without whom this project would not have been possible. During my first class at GU-Q, Professor Pirbhai and I discussed individual agency and determinism; I was adamant that people had agency and he tried to explain to me that it was more complicated than that. Over the past four years and particularly in his mentorship of this project, he has made me a more sophisticated thinker and better able to understand the nuances of the subject. I am tremendously grateful to Dr. Sophie Richter-Devroe, whose work introduced me to the value of oral history and inspired this thesis. Your guidance and advice has been instrumental in the completion of this project. To Amma, Halima and Pharhan Mamu, for their endless support from thousands of miles away. I truly have no idea where I’d be if it weren’t for your faith in me. To all those who have been a part of getting me there: Danish, Fatima, Haider, Fatema and Ayesha. Thank you for supporting me throughout the entire process. I will be grateful forever for your love. Lastly, I am grateful to all the women who shared their remarkable stories of strength and resilience with me, especially the woman whose life this thesis narrates. -

Perhaps in in Our Country He May Be More Known for His Television Roles in Series Like Robin Hood Or Strike Back, but We Have Also Seen Him in Captain America

Exclusive: Richard Armitage Interviewer: Jesús Usero Perhaps in in our country he may be more known for his television roles in series like Robin Hood or Strike Back, but we have also seen him in Captain America. All of this remains tiny in comparison with his most recent job, Thorin, the dwarf leader in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit. An experience that the actor himself says that, if it were the last one of his life, it would make him happy. And he tells us all this in an exclusive interview he gave to Acción. The first thing we’d like to do is thank you for your time and ask what you can tell us about The Hobbit, one of the most anticipated films of the year. Well, I think that the reason that it might be one of the most anticipated films of the year is that it’s going to be a cinematographic event like no one has seen before, which has to do mainly with the return to Middle Earth and the way that Peter has created this work, in 3D, filming at 48 frames per second … I think it will be a very special event. And how did you get a role in such a special project? I got to do an audition for two roles: one for Bard and the other for Thorin, and then I met Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, and I didn’t prepare anything from the film, but rather a mixture of everything in which Thorin believes and all of his characteristics, I read this and we talked about the character, about Middle Earth, about how the film would be. -

Of Spooks and Wraiths Rev

Of Spooks and Wraiths Rev. George M. Schwab, Ph.D. Oct 12, 2015 Isa 13:21 – 22 (BHS) (1599 Geneva Bible) ,But aZiim shall lodge there וְרָ בְצוּ־שָׁם צִיִּים :and their houses shall be full of Ochim וּמָלְאוּ בָתֵּיהֶם א ֹ ִִ֑חים ,Ostriches shall dwell there וְשָׁכְנוּ שָׁם בְּנֹות י ַֽעֲנָה .and the Satyrs shall dance there וּשְׂעִירִ ים יְר קְּדוּ־שָׁ ַֽם׃ ,And Iim shall cry in their palaces וְעָנָה אִיִּים בְּאַלְמנֹותָיו :and dragons in their pleasant palaces וְ תנִּים בְּהֵיכְלֵי ִ֑ע ֹנֶג ,and the time thereof is ready to come וְקָרֹוב לָבֹוא עִתָּהּ .and the days thereof shall not be prolonged וְיָמֶיהָ ֹלא יִמָּשֵׁ ַֽכוּ׃ Geneva Bible has this note, “aWhich were either wild beasts, or fowls, or wicked spirits, whereby Satan deluded man, as by the fairies, goblins, and such like fantasies.” Since demons like to ride on desert fauna, John Geyer (1999) suggests that to mention one might imply the other. His article inspired this essay; my Isaiah bibliography is available. In red are six words needing comment. NASB, NIV, NLT, Amp, etc., identify these as emblematic wildlife that encroached after Babylon’s fall. ESV calls the ziyim, “wild animals;” ’ochim, indoor “howling creatures;” daughters of ya‘anah, “ostrich;” sa‘ir, dancing “wild goats;” ’iyim, palace-dwelling “hyenas;” and tannim, “jackals” in nice mansions. But in Psa 74:14 (a creation poem) the “people of the ziyim” ravened the primordial multi-headed Leviathan; they seem epical there and not mere wasteland scavengers. Look again at sa‘ir. The middle radical is a guttural stop which can be represented with t, yielding “satyr” (per KJV, RSV, Jub, etc.). -

Meta TV in Practice

Meta TV in Practice: A study of the re-use of television texts within contemporary television programmes Annabelle WALLER School of Arts and Media University of Salford, Salford, UK Ph.D. Thesis by Published Works October 2014 1 Contents PART A : WRITTEN SUBMISSION Introduction page 5 Chapter 1 :Nostalgia for Television page 19 Chapter 2 :The Proxy Viewer page 24 Chapter 3 :Transformation Agendas on Television page 34 Chapter 4 : Celebrity and Expertise on Screen page 44 Chapter 5 :Hybridity in Programming page 53 Conclusion page 59 Bibliography page 60 Teleography page 65 PART B : PORTFOLIO OF PRACTICAL WORK (11 DVDs) 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor George McKay, for his guidance on this project and for enabling me to view my past career, and my future one, in an exciting new way. I am also grateful to Sarah, Louis and Rosa for their generous encouragement and tolerance of my absence from episodes of family fun in the production of this work. 3 Abstract This thesis considers how television reflects on its own output in the context of newly created television programmes which seek to reconsider, reframe and re- contextualise the content of television programmes that have already been broadcast. It does this by considering a range of programmes created between 2002 and 2009 as part of my work as a practice based researcher. These programmes cover some of the key genres in contemporary television and reflect the development of forms and themes within the medium. The broad focus of this work is to seek to gain an understanding of what fresh meanings can be derived from re-using existing television content in new programmes that contextualise it with the provision of newly commissioned and created visual content. -

Introduction

Introduction At the conclusion of John le Carré’s novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), the charismatic traitor at the heart of British intelligence articulates one of the key themes of le Carré’s work, declaring his belief that ‘secret services were the only real measure of a nation’s political health, the only real expression of its subconscious’.1 When five years later the novel was adapted for television by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), this metaphor would acquire an additional layer. Asked by director John Irvin how the interior spaces of the intelligence service should be depicted on-screen, le Carré was said to have replied that ‘the dusty offices, the corridors, the elderly office furniture and even the anxiously cranking lifts of MI5 felt like, looked like and had some of the same kinds of people – as the BBC.’2 In fact, this point of comparison was neither unique nor histori- cally specific. Twenty-three years later writer David Wolstencroft was devising the format for a new original BBC spy series which depicted the activities of a counter-terror section within the British Security Service (MI5). In a later Radio Times interview he admitted to the impossibility of gaining access to the real MI5 as part of his research for Spooks (BBC 1, 2002–11), but noted that ‘having been in the BBC quite a lot, I wondered whether it wasn’t quite a good model.’3 Yet the BBC of the 2000s that Wolstencroft used as his inspiration was a very different place to that described by le Carré in the late 1970s. -

UK Spooks STILL Won't Release Bletchley Park Secrets 70 Years on • the Register

7/2/2019 UK spooks STILL won't release Bletchley Park secrets 70 years on • The Register Log in Sign up Forums Personal Tech UK spooks STILL won't release Bletchley Park secrets 70 years on GCHQ staying tight-lipped over codebreaking Mecca's history By Jasper Hamill 6 Feb 2014 at 14:26 82 SHARE ▼ Spooks are still withholding the vital codebreaking secrets of Bletchley Park some 70 years after its boffins first cracked the Nazis' encrypted transmissions. Even though Bletchley has not been an active military facility for more half a century, GCHQ is still refusing to release algorithms which were used to decode Second World War-era messages. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2014/02/06/mi5_still_holds_bletchley_park_secrets/ 1/5 7/2/2019 UK spooks STILL won't release Bletchley Park secrets 70 years on • The Register The team of volunteers working to restore legendary computers such as Tunny, Colossus and the Heath Robinson codebreaking machine told The Register that their incredibly precise and painstaking work was made all the more difficult due to spooks' refusal to release every single detail of the code-cracking machines. Their revelation raises the tantalising prospect that there are yet more secrets to be revealed within this vitally important World War II site. A Wren reenactor at Bletchley Park Wartime secrets still under lock and key John Gallehawk, 86, has volunteered at the National Museum of Computing for more than 15 years, where he has intensively researched the computers which were instrumental in Britain's war effort. We caught up with him yesterday at a celebration of the 70th anniversary of Bletchley's first successful interception and decryption of a German transmission. -

Alex Lanipekun Actor

Alex Lanipekun Actor Royal Academy of Dramatic Art 2005-7. BBC Radio Carlton Hobbs Bursary Award 2007 Agents Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Charlotte Davies Assistant [email protected] Cat Palethorpe +44 (0)20 3214 0800 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Television Production Character Director Company DOMINA Tycho Various Fifty Fathoms Productions/Sky RIVIERA SERIES 2 Raafi (Regular) Various Sky Atlantic TROY Pandarus Owen Harris Kudos Ltd SPARK Christian Lavelle James Kent ABC A.D – Beyond the Asher Brian Kelly NBC - LightWorkers Media Bible KILLING JESUS Hyrcanus Christopher Scott Free Productions/ National Menaul Geographic Channel United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company HOMELAND Hank Wonham Lesli Linka Glatter Showtime Networks THE MISSING Chris Tom Shankland Company Pictures 24: LIVE ANOTHER James Harman Various 20th Century Fox Television DAY LONDON IRISH Dr. Lewin Tom Marshall Company Pictures WAY TO GO Brad Jeff Greenstein BBC BIG BAD WORLD Steve Tristram Shapiro Objective Productions COMING UP Andy David Stoddart Touchpaper/Channel 4 BORGIAS Mohammed LB TV Productions DEATH IN Benjamin Alfred Lot Red Planet Pictures PARADISE BEING HUMAN Saul BBC BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE Tiger David Kerr BBC SPOOKS Ben Kaplan, Kudos regular TALK TO THE Devil's Advocate