27 September 2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1674 HON

E1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 1, 2007 INTRODUCTION OF THE UNI- Because of decades of refusal by Congress He has managed several successful local VERSAL PRE-KINDERGARTEN to approve the large sums necessary for uni- and State political campaigns. Mr. Pugh AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDU- versal health coverage, the Universal Pre-K served as chair of the Saginaw County Rev- CATION ACT OF 2007 Act encourages school districts across the erend Jesse Jackson for President Committee United States to apply to the Department of in 1984 and 1988. Rev. Jesse Jackson won in HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON Education for grants to establish three and Saginaw County in 1984. In 1988, again under OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA four-year-old kindergartens. Grants funded Mr. Pugh’s leadership, Jackson won the Sagi- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES under Title IV of the Elementary and Sec- naw district. Mr. Pugh served as a delegate to ondary Education Act, ESEA, would be avail- the National Democratic Convention in 1988 Tuesday, July 31, 2007 able to school systems which agree in turn to and 1992. Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, I am intro- use the experience acquired with the Federal His community involvement includes: found- ducing today the Universal Pre-kindergarten funding provided by my bill to then move for- ing board member of the Ruben Daniels Edu- and Early Childhood Education Act of 2007 ward, where possible, to phase in three and cational Foundation, member of Saginaw (Universal Pre-K) to begin the process of pro- four-year-old kindergartens for all children in County Mental Health Authority, chair of the viding universal, public school pre-kinder- the school district in regular classrooms with Saginaw Branch NAACP ACT–SO Program, garten education for every child, regardless of teachers equivalent to those in other grades member of Zion Missionary Baptist Church income. -

India: SIKHS in PUNJAB 1994-95

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/SIKHS IN P... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper INDIA SIKHS IN PUNJAB 1994-95 February 1996 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents MAP 1. INTRODUCTION 2. BACKGROUND 2.1 Situation in Punjab 2.2 Sikhs in India 3. MILITANCY 3.1 Beant Singh AssassinationMilitant Strength 3.2 Status of Previously Captured or Surrendered Militants 4. THE PUNJAB POLICE 4.1 Human Rights Abuses and Corruption 4.1.1 Findings of National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) 4.1.2 Abuse in Custody 1 of 21 9/17/2013 7:48 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/SIKHS IN P... 4.1.3 Disappearances 4.1.4 Corruption 4.2 Communications and Reach 4.3 Judicial Review 4.4 Human Rights Training 4.5 Status of Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) Cases NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES MAP See original. 1. INTRODUCTION This paper is intended to serve as an update on the human rights situation for Sikhs in the Indian state of Punjab. -

The Sikhs of the Punjab Revised Edition

The Sikhs of the Punjab Revised Edition In a revised edition of his original book, J. S. Grewal brings the history of the Sikhs, from its beginnings in the time of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, right up to the present day. Against the background of the history of the Punjab, the volume surveys the changing pattern of human settlements in the region until the fifteenth century and the emergence of the Punjabi language as the basis of regional articulation. Subsequent chapters explore the life and beliefs of Guru Nanak, the development of his ideas by his successors and the growth of his following. The book offers a comprehensive statement on one of the largest and most important communities in India today j. s. GREWAL is Director of the Institute of Punjab Studies in Chandigarh. He has written extensively on India, the Punjab, and the Sikhs. His books on Sikh history include Guru Nanak in History (1969), Sikh Ideology, Polity and Social Order (1996), Historical Perspectives on Sikh Identity (1997) and Contesting Interpretations of the Sikh Tradition (1998). Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDONJOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Associate editors C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College J F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922 and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and describe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the past fifty years. -

PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO.1.5 AUTHOR: Dr

M.A. (Political Science) Part II 39 PAPER-VII (OPTION-II) M.A. (Political Science) PART-II PAPER-VII (OPTION-II) Semester-IV (PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO.1.5 AUTHOR: Dr. G. S. BRAR SIKH MILITANT MOVEMENT IN PUNJAB Punjab witnessed a very serious crisis of Sikh militancy during nineteen eighties till a couple of years after the formation of the Congress government in the state in 1992 under the Chief Ministership of late Beant Singh. More than thirty thousand people had lost their lives. The infamous ‘Operation Blue Star’ of 1984 in the Golden Temple, the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards and the subsequent anti-Sikh riots left a sad legacy in the history of the country. The Sikhs, who had contributed to the freedom of the country with their lives, were dubbed as anti-national, and the age-old Hindu-Sikh unity was put on test in this troubled period. The democratic movement in the state comprising mass organizations of peasants, workers, government employees, teachers and students remained completely paralysed during this period. Some found the reason of Sikh militancy in ‘the wrong policies pursued by the central government since independence’ [Rai 1986]. Some others ascribed it to ‘an allegedly slow process of alienation among a section of the Punjab population in the past’ [Kapur 1986]. Still others trace it to ‘the rise of certain personalities committed to fundamentalist stream of thought’ [Joshi 1984:11-32]. The efforts were also made to trace its origin in ‘the socio-economic developments which had ushered in the state since the advent of the Green Revolution’ [Azad 1987:13-40]. -

Militancy and Counter-Militancy Operations: Changing Patterns and Dynamics of Violence in Punjab, 1978 to 1993

65 Satnam Singh Deol: Militancy in Punjab Militancy and Counter-Militancy Operations: Changing Patterns and Dynamics of Violence in Punjab, 1978 to 1993 Satnam Singh Deol Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar _______________________________________________________________ How did the patterns of violence committed by Sikh militants and the state security forces change during different phases of the insurgency from 1978 to 1993 and, most importantly, what explains the difference in these patterns? This study attempts to answer these questions. It argues that this variation in the patterns and dynamics of violence can be explained by changing socio-political circumstances and compulsions during this period. The violence committed by the militants intensified until this violence was eventually delegitimized by the common Sikh masses due to changing dynamics within the militant movement and the nature of its violence. Simultaneously, the violence committed by the state overpowered the militancy only after it was firmly backed by the political regimes in power, including providing de facto legal impunity to the police and security forces for a brutal and controversial counterinsurgency campaign. Thus, this article disaggregates the various phases of violence committed by both the militants and the state from 1978 to 1993, and examines the interrelationship between the forms of violence committed by both sides in the conflict. Important observations emerging from this empirical study are offered in the concluding section. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction and Historical Background The Sikhs, even after being defeated by the British and losing their political control in the north-western region, maintained a unique religious, ethnical and political legacy, which was separate from Hindus in various domains (Singh, 1963; Dhillon, 2006). -

Postscript: November 1985

Postscript: November 1985 In the time since the typescript of this book went to the publishers, events have highlighted a number of its themes. Perhaps the most important - the agreement between Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Harchand Singh Longowal, announced on 24 July 1985 1 - emphasised a basic argument of the book: that political decisions, rather than inexorable social forces, determine the form and intensity of ethnIc conflict. On the face of it, Punjab's problems should have been more intractable by July 1985 than ever before. The mood of Sikhs, for example, should have been more intransigent. The army had been deployed in Punjab for more than a year, the Sikhs there complained of violations of civil rights. In addition, Sikhs everywhere shared the anger and humiliation, if not the loss and death, of those who suffered in the rioting following Mrs Gandhi's murder. 'National opinion', too, might have been expected to have hardened against Sikhs. The death of more than 80 people in terrorist bombings in New Delhi and other parts of north India on 11 and 12 May ought to have embittered feelings further, as should the mysterious crash of an Air India jumbo jet off the coast of Ireland on 23 June which killed more than 320 people. Furthermore, the 'Memorandum of Settlement' of July 1985 between the central government and Longowal's Akali Dal appeared to contain nothing new. Indeed, wrote The Tribune, it ran 'along lines known and agreed upon almost two years ago'.2 The 'Indian Talks' section of this book (pp. -

2012 Assembly Elections in Punjab: Ascendance of a State Level Party

255 Ashutosh Kumar: Punjab Assembly Elections 2012 Assembly Elections in Punjab: Ascendance of a State Level Party Ashutosh Kumar Punjab University, Chandigarh _______________________________________________________________ The 2012 Assembly Elections in Punjab received attention for being the first elections in post-1966 reorganised Punjab to witness return to power of an incumbent party regime. The elections also saw the emergence of a new set of political leadership, most notably the rise of Sukhbir Badal, the SAD President who led the campaign and crafted the Akali victory. The rise and fall of Manpreet Badal, the founder President of Punjab Peoples Party in the role of the ‘challenger’ was another notable feature. The social and spatial patterns of electoral outcome, as revealed in the CSDS post-poll survey data, showed that the consistent efforts of the Akali Dal to broaden its support base while retaining its core social constituency in order to shed/lessen its dependency over the BJP has started bearing fruits. The Congress suffered an unexpected defeat primarily due to its leadership failure. ____________________________________________________________ Rise of State Level Parties The newly acquired significance of states as the platforms where electoral politics unfold in varying forms in recent India can be attributed to the fact that political articulation and mobilization of the people for electoral purposes increasingly swerve around identities formed or invented along ethno-regional lines. As the ethnic categories are mostly confined to a particular region or regions of a state, so any form of mobilisation or assertion in the shape of collective claims making takes place invariably at regional level, giving primacy to ‘region’ over the ‘nation.’1 The political parties strive first to gain and consolidate a ‘core constituency’ in the form of the support of a single numerically and economically significant caste/ community or alternatively a cluster of castes/communities at state/regional level before they go to broaden their support base. -

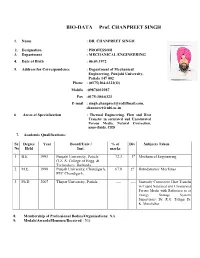

BIO-DATA Prof

BIO-DATA Prof. CHANPREET SINGH 1. Name : DR. CHANPREET SINGH 2. Designation : PROFESSOR 3. Department : MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 4. Date of Birth : 06.03.1972 5. Address for Correspondence : Department of Mechanical Engineering, Punjabi University, Patiala 147 002 Phone : (0175)304-6323(O) Mobile :09876032987 Fax :0175-304-6323 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] 6 Areas of Specialization : Thermal Engineering, Flow and Heat Transfer in saturated and Unsaturated Porous Media, Natural Convection, nano-fluids, CFD 7. Academic Qualifications: Sr. Degree Year Board/Univ./ % of Div Subjects Taken No Held Inst. marks . 1 B.E. 1993 Punjabi University, Patiala. 72.3 1st Mechanical Engineering G.Z. S. College of Engg. & Technology, Bathinda. 2 M.E. 1998 PPanjabatiala University, Chandigarh, 67.8 1st Rotodynamic Machines PEC Chandigarh. 3 Ph.D 2007 Thapar University, Patiala ---- ---- Unsteady Convective Heat Transfer in Liquid Saturated and Unsaturated Porous Media with Reference to an Energy Storage System. Supervisors: Dr. R.G. Tathgir Dr. K. Muralidhar 8. Membership of Professional Bodies/Organisations: NA 9. Medals/Awards/Honours/Received : NA 10. Scholarships: i) M.E. GATE scholarship ii) Matriculation, Middle and Primary Level State scholarship 11. Details of Experience: S. Name of the Position Duration Major Job Responsibilities and No Inst./Employer Held Nature of Experience 1.. Thapar Polytechnic, Patiala Lecturer 27.9.95 to Teaching, Extra-curricular Activities 27.3.97 and Research 2. Thapar Institute of Engg. & Lecturer 27.3.97 to Teaching, Extra-curricular Activities Technology, Patiala 18.12.2006 and Research 4 Punjabi University, Patiala Reader 19.12.2006 to Teaching, Extra-curricular Activities 17.12.2009 and Research 5 Punjabi University, Patiala Associate 17.12. -

G:\Lessons\Lesson (2020-21)\M.A

M.A. (POLITICAL SCIENCE) PART-II PAPER-VII (OPTION-II) (PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO. 1.2 AUTHOR : DR. KEHAR SINGH Reorganisation of Punjab in 1966- Its Background and Impact on State Politics Indian sub-continent was divided in 1947 in two parts, India and Pakistan, to propitate the communal demigods. The whole of non-Muslim population had to migrate to the Indian side of the border. Similarly, a large majority of the Muslims in East Punjab chose to opt for Pakistan as their fatherland. The whole-sale loot carnage and plunder perpetrated by the communities against each other in their communal frenzy is a sad proof of the devil in man and what havoc can it play if left unchained. The partition of the country solved no problem but created many. The unfulfilled aspirations of the Sikhs a minority community in the preparation and partitioned Punjab, was one of the political problems which the leadership of India had to confront with. The partition had created a new situation. The communal parties of pre- partitioned days continued to have their sway in the Punjab after the independence of India except that three pronged communal politics changed into two pronged Hindu Sikh politics. The rehabilitation of the refugees in the areas upto Ghaggar resulted in a Sikh majority in certain tehsils of East Punjab where as in the Princely States, Sikhs constituted a majority of the population. According to 1951 Census, there were 63.3 per cent Hindus an 33.4 per cent Sikhs is Pepsu. The Sikh and Hindu percentage in the population was 49.3 and 48.8 percentage of 62.3 and the Sikhs 35. -

EXTERNAL (For General Distribution) AI Index: ASA 20/46/92 Distr: UA/SC

EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: ASA 20/46/92 Distr: UA/SC UA 278/92 Fear of Torture 4 September 1992 INDIA: Malwinder Singh Malli, Journalist Malwinder Singh Malli, a journalist for the Punjabi Tribune and former General Secretary of the Punjab Human Rights Organization was reportedly arrested by police on 23 August 1992. He is being held under the National Security Act probably in the Sangrur District. Malwinder Singh Malli was travelling on a bus from Dhury to Malerkotla when the police stopped the bus and took him away. Mr Malli is a close associate of Ram Singh Billing, another Sikh journalist, who was reportedly taken into custody on 3 January 1992 (See Urgent Action 17/92, ASA 20/11/92, 14 January 1992). Mr Billing's whereabouts are still unknown. Both Malwinder Singh Malli and Ram Singh Billing had been involved in bringing legal action on behalf of two young Sikh detainees and had filed a petition on their behalf in the Punjab and Haryana High Court in Chandigarh. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Amnesty International regularly receives reports of torture, "disappearances" and unacknowledged detention of people arrested in Punjab on suspicion of being members or sympathizers of one of the Sikh opposition groups advocating a separate Sikh state, "Khalistan". In some cases the detainees are eventually found to have died in custody, while others are found to have been deliberately killed in custody although official reports say they died in "encounters" with the police. Even though legal safeguards against torture and unacknowledged detention exist in India's ordinary criminal law and procedural code, they are often simply not adhered to and prisoners are held in illegal detention for weeks and sometimes months under special legislation granting the security forces arbitrary powers to arrest and detain people without ordinary legal safeguards and without charge or trial. -

Extensions of Remarks E1234 HON. CHARLES B

E1234 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks June 25, 1998 said Charlene Bridges, president of the HONORING THE LATE LEONARD On January 2, 1993, the police claimed that Lamar school. The other Colorado schools HARPER Jathedar Kaunke had escaped. This claim was are at Trinidad State Junior College and the false. He had been killed the day before. Ac- Colorado School of Trades in Lakewood. HON. CHARLES B. RANGEL cording to a news article, he was murdered by Bridges' husband, J. Earl Bridges, is direc- OF NEW YORK being torn in half, similar to the way that the tor and chief instructor. He has been a gun- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES driver for another religious leader, Bbab smith for 15 years and has been teaching the Charan Singh, was murdered by the Indians. craft for the past six. Thursday, June 25, 1998 The human-rights activists created a com- Since it opened, the academy ``has worked Mr. RANGEL. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to mission to look into the matter. According to on no less than 3,000 firearms, and maybe honor the late Leonard Harper on his remark- their statement, they seek ``an appointment four have been returned to redo something or able achievements in the field of theater and with the Chief Minister of Punjab to acquaint because we overlooked something,'' Earl stage shows. Bridges said. him with its findings and to demand registra- Mr. Harper was one of the leading figures tion of a case against the culprits.'' They point- In addition to learning how to build their who transformed Harlem into a cultural center own rifles from stock to trigger assembly to ed out that this demand ``is no more than a re- during the 1920's.