PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO.1.5 AUTHOR: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics of Genocide

I THE BACKGROUND 2 1 WHY PUNJAB? Exit British, Enter Congress In 1849 the Sikh empire fell to the British army; it was the last of their conquests. Nearly a hundred years later when the British were about to relinquish India they were negotiating with three parties; namely the Congress Party largely supported by Hindus, the Muslim League representing the Muslims and the Akali Dal representing the Sikhs. Before 1849, the Satluj was the boundary between the kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and other Sikh states, such as Patiala (the largest and most influential), Nabha and Jind, Kapurthala, Faridkot, Kulcheter, Kalsia, Buria, Malerkotla (a Muslim state under Sikh protection). Territory under Sikh rulers stretched from the Peshawar to the Jamuna. Those below the Satluj were known as the Cis-Satluj states. 3 In these pre-independence negotiations, the Akalis, led by Master Tara Singh, represented the Sikhs residing in the territory which had once been Ranjit Singh’s kingdom; Yadavindra Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, spoke for the Cis- Satluj states. Because the Sikh population was thinly dispersed all over these areas, the Sikhs felt it was not possible to carve out an entirely separate Sikh state and had allied themselves with the Congress whose policy proclaimed its commitment to the concept of unilingual states with a federal structure and assured the Sikhs that “no future Constitution would be acceptable to the Congress that did not give full satisfaction to the Sikhs.” Gandhi supplemented this assurance by saying: “I ask you to accept my word and the resolution of the Congress that it will not betray a single individual, much less a community .. -

Nishaan – Blue Star-II-2018

II/2018 NAGAARA Recalling Operation ‘Bluestar’ of 1984 Who, What, How and Why The Dramatis Personae “A scar too deep” “De-classify” ! The Fifth Annual Conference on the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, jointly hosted by the Chardi Kalaa Foundation and the San Jose Gurdwara, took place on 19 August 2017 at San Jose in California, USA. One of the largest and arguably most beautiful gurdwaras in North America, the Gurdwara Sahib at San Jose was founded in San Jose, California, USA in 1985 by members of the then-rapidly growing Sikh community in the Santa Clara Valley Back Cover ContentsIssue II/2018 C Travails of Operation Bluestar for the 46 Editorial Sikh Soldier 2 HERE WE GO AGAIN: 34 Years after Operation Bluestar Lt Gen RS Sujlana Dr IJ Singh 49 Bluestar over Patiala 4 Khushwant Singh on Operation Bluestar Mallika Kaur “A Scar too deep” 22 Book Review 1984: Who, What, How and Why Jagmohan Singh 52 Recalling the attack on Muktsar Gurdwara Col (Dr) Dalvinder Singh Grewal 26 First Person Account KD Vasudeva recalls Operation Bluestar 55 “De-classify !” Knowing the extent of UK’s involvement in planning ‘Bluestar’ 58 Reformation of Sikh institutions? PPS Gill 9 Bluestar: the third ghallughara Pritam Singh 61 Closure ! The pain and politics of Bluestar 12 “Punjab was scorched 34 summers Jagtar Singh ago and… the burn still hurts” 34 Hamid Hussain, writes on Operation Bluestar 63 Resolution by The Sikh Forum Kanwar Sandhu and The Dramatis Personae Editorial Director Editorial Office II/2018 Dr IJ Singh D-43, Sujan Singh Park New Delhi 110 -

Khalistan & Kashmir: a Tale of Two Conflicts

123 Matthew Webb: Khalistan & Kashmir Khalistan & Kashmir: A Tale of Two Conflicts Matthew J. Webb Petroleum Institute _______________________________________________________________ While sharing many similarities in origin and tactics, separatist insurgencies in the Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have followed remarkably different trajectories. Whereas Punjab has largely returned to normalcy and been successfully re-integrated into India’s political and economic framework, in Kashmir diminished levels of violence mask a deep-seated antipathy to Indian rule. Through a comparison of the socio- economic and political realities that have shaped the both regions, this paper attempts to identify the primary reasons behind the very different paths that politics has taken in each state. Employing a distinction from the normative literature, the paper argues that mobilization behind a separatist agenda can be attributed to a range of factors broadly categorized as either ‘push’ or ‘pull’. Whereas Sikh separatism is best attributed to factors that mostly fall into the latter category in the form of economic self-interest, the Kashmiri independence movement is more motivated by ‘push’ factors centered on considerations of remedial justice. This difference, in addition to the ethnic distance between Kashmiri Muslims and mainstream Indian (Hindu) society, explains why the politics of separatism continues in Kashmir, but not Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Of the many separatist insurgencies India has faced since independence, those in the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have proven the most destructive and potent threats to the country’s territorial integrity. Ostensibly separate movements, the campaigns for Khalistan and an independent Kashmir nonetheless shared numerous similarities in origin and tactics, and for a brief time were contemporaneous. -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

SIKH1SM and the NIRANKARI MOVEMENT 2-00

SIKH1SM and THE NIRANKARI MOVEMENT 2-00 -00 -00 -00 2-00 -00 00 00 00 ACADEMY OF SIKH RELIGION AND CULTURE 1, Dhillon Marg, Bhupinder Nagar PAT I ALA SIKHISM and THE NIRANKARI MOVEMENT ACADEMY OF SIKH RELIGION AND CULTURE 1. Dhillon Marg, Bhupinder Nagar PATIALA ^^^^^ Publisher's Note Nirankari movement was founded as renaissance of Sikh religion but lately an off-shoot of Nirankaris had started ridiculing Sikh Religion and misinterpreting Sikh scriptures for boosting up the image of their leader who claims to be spiritual head; God on Earth and re-incarnate of Shri Rama, Shri Krishna, Hazrat Mohammed, Holy Christ and Sikh Gurus. The followers of other religions did not react to this blasphemy. The Sikhs, however, could not tolerate the irreverance towards Sikh Gurus, Sikh religion and Sikh scrip tures and protested against it. This pseudo God resented the protest and became more vociferous in his tirade against Sikhs, their Gurus and their Scriptures. His temerity resulted in the massacre of Sikhs at Amritsar on 13th April, 1978 (Baisakhi day) at Kanpur on 26th September, 1978 and again in Delhi on 5th, November 1978. This booklet is published to apprise the public of the back ground of Nirankaris, the off-shoot of Nirankaris, the cause of controversy and the aftermath. It contains three articles : one, by Dr. Ganda Singh, a renowned historian, second, by Dr. Fauja Singh of Punjabi University, Patiala. and third, by S. Kapur Singh, formerly of I.C.S. cadre. A copy of the report of the Enquiry Committee on the Happen ings at Kanpur, appointed by the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee whose members were S. -

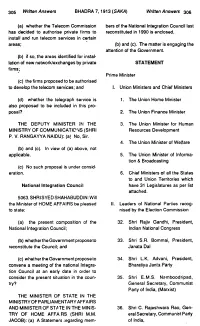

(A) Whether the Telecom Commission Has Decided to Authorise Private

305 Written Answers BHADRA 7.1913 (SAKA) Written Answers 306 (a) whether the Telecom Commission bers of the National Integration Council last has decided to authorise private firms to reconstituted in 1990 is enclosed. install and run telecom services in certain areas; (b) and (c). The matter is engaging the attention of the Government. (b) if so, the areas identified for instal- lation of new network/exchanges by private STATEMENT firms; Prime Minister (c) the firnis proposed to be authorised to develop the telecom services; and I. Union Ministers and Chief Ministers (d) whether the telegraph service is 1 . The Union Home Minister also proposed to be included in this pro- posal? 2. The Union Finance Minister THE DEPUTY MINISTER !N THE 3. The Union Minister for Human MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIC'>IS (SHRI Resources Development P. V. RANGAYYA NAIDU); (a) No. Sir. 4. The Unton Minister of Welfare (b) and (c). In view of (a) above, not applicable. 5. The Union Minister of Informa- tion & Broadcasting (c) No such proposal is under consid- eration. 6. Chief Ministers of all the States to and Union Territories which National Integration Council have 31 Legislatures as per list attached. 5063. SHRI SYED SHAHABUDDIN: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased II. Leaders of National Parties recog- to state: nised by the Election Commission (a) the present composition of the 32. Shri Rajiv Gandhi, President, National Integration Council; Indian National Congress (b) whethertheGovernment propose to 33. Shri S.R. Bommai, President, reconstitute the Council; and Janata Dal (c) whether the Government propose to 34. -

Mapping the 'Khalistan' Movement, 1930-1947: an Overview

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 55, Issue No. 1(January - June, 2018) Samina Iqbal * Rukhsana Yasmeen** Kalsoom Hanif *** Ghulam Shabir **** Mapping the ‘Khalistan’ Movement, 1930-1947: An overview Abstract This study attempts to understand the struggle of the Sikhs of the Punjab, during the colonial period (1930-1947), for their separate home-land- Khalistan, which to date have been an unfinished agenda. They still feel they have missed the train by joining hands with the Congress Party. There is strong feeling sometime it comes out in shape of upsurge of freedom of moments in the East Punjab. Therefore it is important to understand what was common understanding of the Sikh about the freedom struggle and how they reacted to national movements and why they filed to achieve a separate homeland-Khalistan. The problem is that the Sikh demands have so been ignored by the British government of India and His Majesty’s Government in England. These demands were also were not given proper attention by the Government of Punjab, Muslim leadership and Congress. Although the Sikhs had a voice in the politics and economic spheres their numerical distribution in the Punjab meant that they were concerted in any particular areas. Therefore they remained a minority and could only achieve a small voting strength under separate electorates. The other significant factor working against the Sikh community was that the leadership representing was factionalized and disunited, thus leading to a lack of united representation during the freedom struggle and thus their demand for the creation of a Sikh state could not become a force to reckon. -

Sikhism Reinterpreted: the Creation of Sikh Identity

Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-16-2014 Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Brittany Fay Puller Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Puller, Brittany Fay, "Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Abstract The iS kh identity has been misinterpreted and redefined amidst the contemporary political inclinations of elitist Sikh organizations and the British census, which caused the revival and alteration of Sikh history. This thesis serves as a historical timeline of Punjab’s religious transitions, first identifying Sikhism’s emergence and pluralism among Bhakti Hinduism and Chishti Sufism, then analyzing the effects of Sikhism’s conduct codes in favor of militancy following the human Guruship’s termination, and finally recognizing the identity-driven politics of colonialism that led to the partition of Punjabi land and identity in 1947. Contemporary practices of ritualism within Hinduism, Chishti Sufism, and Sikhism were also explored through research at the Golden Temple, Gurudwara Tapiana Sahib Bhagat Namdevji, and Haider Shaikh dargah, which were found to share identical features of Punjabi religious worship tradition that dated back to their origins. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1309 HON. GARY L. ACKERMAN HON. EDOLPHUS TOWNS

June 21, 2005 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1309 the academy.’’ The bill directed the Air Force In 2000, Deborah married her long-time best for raising the Sikh flag and making speeches. to develop a plan to ensure that the academy friend, Alvin Benjamin of Glen Head, New The Movement Against State Repression re- maintains a climate free from coercive reli- York. Alvin is the Owner/President of Ben- ports that over 52,000 Sikhs are political pris- gious intimidation and inappropriate proselyt- jamin Development in Garden City, New York. oners in ‘‘the world’s largest democracy.’’ izing. They currently reside in Glen Head, Manhat- More than a quarter of a million Sikhs have As a Coloradan and a Member of the tan, and Highland Beach, Florida. been murdered, according to figures compiled Armed Services Committee, I have been fol- Since her retirement, Mrs. Benjamin has de- from the Punjab State Magistracy. lowing this matter closely and have noted that voted much of her time to charitable organiza- Sikhs are only one of India’s targets. Other Lt. Gen. John Rosa, the Academy’s super- tions dedicated to improving the lives of chil- minorities such as Christians, Muslims, and intendent, has said that the problem is ‘‘some- dren. She is most actively involved with the others have also been subjected to tyrannical thing that keeps me awake at night,’’ and esti- Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, which is repression. More than 300,000 Christians mated it will take 6 years to fix. dedicated to finding a cure for this rare, but have been killed in Nagaland, and thousands The good news is that several reviews of serious blood disease. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1674 HON

E1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 1, 2007 INTRODUCTION OF THE UNI- Because of decades of refusal by Congress He has managed several successful local VERSAL PRE-KINDERGARTEN to approve the large sums necessary for uni- and State political campaigns. Mr. Pugh AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDU- versal health coverage, the Universal Pre-K served as chair of the Saginaw County Rev- CATION ACT OF 2007 Act encourages school districts across the erend Jesse Jackson for President Committee United States to apply to the Department of in 1984 and 1988. Rev. Jesse Jackson won in HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON Education for grants to establish three and Saginaw County in 1984. In 1988, again under OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA four-year-old kindergartens. Grants funded Mr. Pugh’s leadership, Jackson won the Sagi- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES under Title IV of the Elementary and Sec- naw district. Mr. Pugh served as a delegate to ondary Education Act, ESEA, would be avail- the National Democratic Convention in 1988 Tuesday, July 31, 2007 able to school systems which agree in turn to and 1992. Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, I am intro- use the experience acquired with the Federal His community involvement includes: found- ducing today the Universal Pre-kindergarten funding provided by my bill to then move for- ing board member of the Ruben Daniels Edu- and Early Childhood Education Act of 2007 ward, where possible, to phase in three and cational Foundation, member of Saginaw (Universal Pre-K) to begin the process of pro- four-year-old kindergartens for all children in County Mental Health Authority, chair of the viding universal, public school pre-kinder- the school district in regular classrooms with Saginaw Branch NAACP ACT–SO Program, garten education for every child, regardless of teachers equivalent to those in other grades member of Zion Missionary Baptist Church income. -

Vicissitudes of Gurdwara Politics

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Vicissitudes of Gurdwara Politics YOGESH SNEHI Vol. 49, Issue No. 34, 23 Aug, 2014 Yogesh Snehi ([email protected]) is a fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla. The demand of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee to oversee the functioning of gurdwaras represents the legitimate aspirations of the Sikhs of Haryana and more significantly, inversion against almost absolute hegemony of SAD over the management of Sikh shrines through Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. The situation over the formation of Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (HSGPC) and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) dominated Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee’s (SGPC) opposition to it, has entered into a confrontational stage endangering the peace and harmony in the region. Despite the enactment of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Act 2014, the SGPC has refused to vacate the gurdwaras in Haryana for HSGPC. While Gurdwara Chhevin Patshahi at Kurukshetra becomes the centre-stage for a long-drawn battle, HSGPC has taken possession of six gurdwaras in the state (Sedhuraman 2014).[1] After clashes between the supporters of SGPC and HSGPC, the Supreme Court has ordered maintenance of status-quo and postponed the next hearing for 25 August 2014. This recent controversy has its roots both in the movement for gurdwara reforms (1920s), which sought to purge Sikhism from the polluting effects of non-Sikh practices, as well as the reorganisation of Punjab province in 1966. It also raises some fundamental issues about the residue of colonialism in the 21st century India. Historicising Gurdwara Reform More than nine decades ago in 1921, Punjab was embroiled in a controversy over misuse of the premises of Gurdwara Janam Asthan at Nankana Sahib (now in Pakistan) for narrow self-interests by the hereditary custodian Udasi Mahant Narain Das who was a Sehajdari Sikh (Yong 1995: 670).[2] Mahants had traditionally inherited the custodianship of most gurdwaras since pre-colonial Punjab[3] and had allegedly started behaving like sole proprietors.